Craco

Craco is a ghost town and comune in the province of Matera, in the southern Italian region of Basilicata. It was abandoned towards the end of the 20th century due to natural disasters. The abandonment has made Craco a tourist attraction and a popular filming location. In 2010, Craco was included in the watch list of the World Monuments Fund.[3]

Craco | |

|---|---|

| Comune di Craco | |

The old town of Craco | |

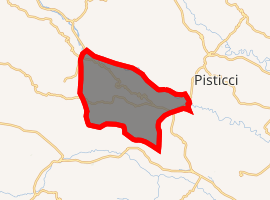

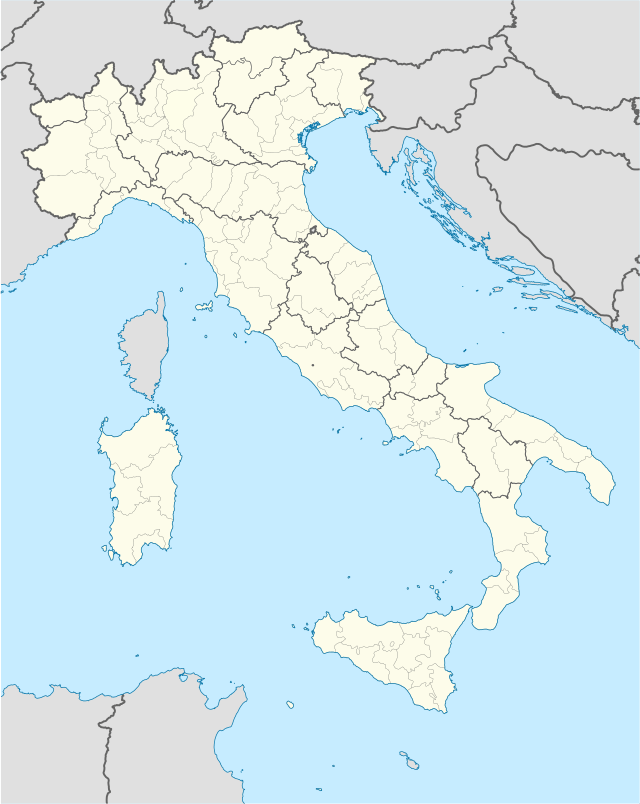

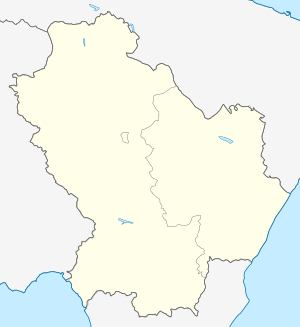

Location of Craco

| |

Craco Location of Craco in Italy  Craco Craco (Basilicata) | |

| Coordinates: 40°22′43.16″N 16°26′25.25″E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Basilicata |

| Province | Matera (MT) |

| Frazioni | Craco Peschiera |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Vincenzo Lacopeta |

| Area | |

| • Total | 77.04 km2 (29.75 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 391 m (1,283 ft) |

| Population (December 2008)[2] | |

| • Total | 773 |

| • Density | 10/km2 (26/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Crachesi |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 75010 |

| Dialing code | 0835 |

| Patron saint | San Vincenzo Martire di Craco |

| Website | Official website |

Geography

Craco is about 40 kilometres (25 mi) inland from the Gulf of Taranto. The town was built on a very steep summit for defensive reasons, giving it a striking appearance and distinguishing it from the surrounding land. The centre, built on the highest side of the town, faces a ridge which runs steeply to the southwest, where newer buildings exist. The town sits atop a 400-metre-high (1,300 ft) cliff that overlooks the Cavone River valley. Throughout the area are many vegetation-less mounds called calanchi (badlands) formed by intensive erosion.

History

Tombs have been found dating from the 8th century BC. Around 540 BC, the area was inhabited by Greeks who moved inland from the coastal town of Metaponto. The town's name can be dated to 1060 AD, when the land was the possession of Arnaldo, Archbishop of Tricarico, who called the area Graculum, which means in Latin "little plowed field". This long association of the Church with the town had a great influence on the inhabitants.

From 1154 to 1168, the control of the village passed to a nobleman, Eberto, probably of Norman origin, who established the first feudal control over the town. Then in 1179, Roberto of Pietrapertosa became the landlord of Craco. Under Frederick II, Craco was an important military center and the Castle Tower became a prison.

In 1276, a university was established in the town. During the 13th century, Craco became feudal tenure of Muzio Sforza. The population increased from 450 (1277), to 655 (1477), to 1,718 (1532), until reaching 2,590 in 1561; and averaged 1,500 in succeeding centuries. By the 15th century, four large palazzi had developed in the town: Palazzo Maronna near the tower, Palazzo Grossi near the big church, Palazzo Carbone on the Rigirones property, and Palazzo Simonetti. During 1656, a plague struck, with hundreds dying and reducing the number of families in the town.

By 1799, with the proclamation of the Parthenopean Republic, the townspeople overthrew the Bourbon feudal system. Innocenzo De Cesare returned to Naples, where he had studied, and promoted an independent municipality. The republican revolution lasted few months and Craco returned under the Bourbon monarchy. Subsequently, the town fell under the control of the Napoleonic occupation. Bands of brigands, supported by the Bourbon government in exile, attacked Craco on July 18, 1807, plundering and killing the pro-French notables.

By 1815, the town was large enough to divide it into two districts: Torrevecchia, the highest area adjacent to the castle and tower; and Quarter della Chiesa Madre, the area adjacent to San Nicola's Church. After the unification of Italy, in 1861 Craco was conquered by the bands of brigands headed by Carmine Crocco.

With the end of the civil strife, the greatest difficulty the town faced became environmental and geological. From 1892 to 1922, over 1,300 Crachesi migrated to North America mainly due to poor agricultural conditions. In 1963, Craco began to be evacuated due to a series of landslides and the inhabitants moved to the valley of Craco Peschiera. The landslides seem to have been provoked by works of infrastructure, sewer and water systems.

In 1972 a flood worsened the situation further, preventing a possible repopulation of the historic centre. After the 1980 Irpinia earthquake, the ancient site of Craco was completely abandoned.

In 2007, the descendants of the emigrants of Craco in the United States formed the "Craco Society", a non-profit organization which preserves the culture, traditions, and history of the comune.

In popular culture

Cinema

Craco has been the setting of many movies, and was the setting for the suicide of Judas in The Passion of The Christ (2004), by Mel Gibson.[4] Other films shot inside or near the ghost town include:

- La lupa (1953), by Alberto Lattuada[5]

- Christ Stopped at Eboli (1979), by Francesco Rosi[5]

- King David (1985), by Bruce Beresford[5]

- Saving Grace (1986), by Robert M. Young[5]

- The Sun Also Shines at Night (1990), by Paolo and Vittorio Taviani[5]

- The Nymph (1996), by Lina Wertmüller[6]

- The Nativity Story (2006), by Catherine Hardwicke[5]

- Quantum of Solace (2008), by Marc Forster[5]

- Basilicata Coast to Coast (2010), by Rocco Papaleo[5]

Television

- The ancient site has been one of the filming sets for the Italian TV series Classe di ferro (1989-1991), by Bruno Corbucci.[5]

- Craco has been chosen among the locations for the Brazilian telenovela O Rei do Gado (1996-1997), directed by Luiz Fernando Carvalho.[7]

- In 2015 the ghost town was the setting for a Japanese Pepsi commercial.[8]

People

- Vincenzo, Martyr of Craco

- Director David O. Russell's maternal grandfather was originally from Craco[11]

See also

References

- "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Istat. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- All demographics and other statistics from the Italian statistical institute (Istat)

- "Historic center of Craco". wmf.org. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- "The Passion of the Christ". movie-locations.com. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "Craco Cinema 2014" (PDF). comune.craco.mt.it. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- "Craco Cinema 2014" (in Italian). isassidimatera.com. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- "O Rei Do Gado: Bastidores". teledramaturgia.com.br. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- "Visit these 3 Places in Italy before they're Ruined by Tour Groups". thedailymeal.com. 8 August 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- "Ödland – Sankta Lucia". odland.fr. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- "Hauschka – UK Headline Tour & 'Elizabeth Bay' Video Premiere". folkradio.co.uk. 30 January 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- "David O. Russell to Receive Italian-American Icon Award". hollywoodreporter.com. 13 October 2014. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Craco. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Craco. |