Tatars of Romania

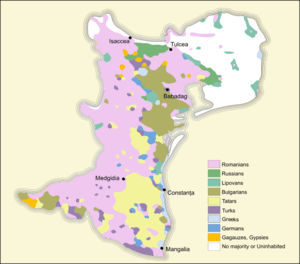

Tatars of Romania (Romanian: Tătarii din România) or Dobrujan Tatars[1] (Crimean Tatar: Dobruca tatarları), are a Turkic ethnic group, have been present in Romania since the 13th century. According to the 2011 census, 20,282 people declared their nationality as Tatar, most of them being of Crimean Tatar extraction and living in Constanţa County. They are the main component of the Muslim community in Romania.

History

Middle Ages

The roots of the Crimean Tatar community in Romania began with the Cuman migration in the 10th century. Even before the Cumans arrived, other Turkic people like the Huns and the Bulgars settled in this region. The Tatars first reached the mouths of the Danube in the mid-13th century at the height of the power of the Golden Horde. In 1241, under the leadership of Kadan, the Tatars crossed the Danube, conquering and devastating the region. The region was probably not under the direct rule of the Horde, but rather, a vassal of the Bakhchisaray Khan.[2] It is known from Arab sources that at the end of the 13th century and the beginning of the 14th century that descendants of the Nogai Horde settled in Isaccea. Another Arab scholar, Ibn Battuta, who passed through the region in 1330–31, talks about Baba Saltuk (Babadag) as the southernmost town of the Tatars.[2]

The Golden Horde began to lose its influence after the wars of 1352-1359 and at the time, a Tatar warlord Demetrius is noted defending the cities of the Mouths of the Danube. In the 14th and 15th centuries the Ottoman Empire colonized Dobruja with Nogais from Bucak. Between 1593 and 1595 Tatars from Nogai and Bucak were also settled to Dobruja. (Frederick de Jong)

Early modern period

Toward the end of the 16th century, about 30,000 Nogai Tatars from the Budjak were brought to Dobruja.[3]

After the Russian annexation of Crimea in 1783 Crimean Tatars began emigrating to the Ottoman coastal provinces of Dobruja (today divided between Romania and Bulgaria). Once in Dobruja most settled in the areas surrounding Mecidiye, Babadag, Köstence, Tulça, Silistre, Beştepe, or Varna and went on to create villages named in honor of their abandoned homeland such as Şirin, Yayla, Akmecit, Yalta, Kefe or Beybucak.

Late modern period

From 1783 to 1853 tens of thousands of Crimean Tatars and Nogais emigrated to the Rusçuk region which subsequently became known as "Little Tartary". Following the Russian conquest of 1812, Nogais from Bucak also immigrated to Dobruja. Tatars who settled in Dobruja before the great exodus of 1860 were known as Kabail. They formed the Kabail Tatar squadron in the Nizam-ı Cedid (New Order) army of sultan Selim III. They played a key role in Mahmud II's struggle with Mehmet Ali Pasha of Egypt, suppressed rebellions in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kurdistan, and the Arab provinces and served with the Ottomans during the Crimean War.

Tatars together with Albanians served as gendarmes, who were held in high esteem by the Ottomans and received special tax privileges. The Ottoman's additionally accorded a certain degree of autonomy for the Tatars who were allowed governance by their own kaymakam, Khan Mirza. The Giray dynasty (1427 - 1878) multiplied in Dobruja and maintained their respected position. A Dobrujan Tatar, Kara Hussein, was responsible for the destruction of the Janissary corps on orders from Sultan Mahmut II.

From 1877-1878 it is estimated that between 80,000 and 100,000 Crimean Tatars emigrated from Dobruja to Anatolia, which continued in smaller numbers until World War I. The reasons for the emigration were several: In 1883 the Romanian government enacted laws requiring compulsory military service for all Romanian subjects including Tatars who were concerned that serving a Christian army was not in accord with their Muslim identity. Other reasons included the 1899 famine in Dobruja, a series of laws from 1880 to 1885 regarding confiscation of Tatar and Turkish land, and the World War I (1916–18) which devastated the region.

Early 20th century to WWII

A unique Crimean Tatar national identity in Dobruja began to emerge in the last quarter of the 19th century.[4] When Ismail Gasprinski, considered by many to be the father of Crimean Tatar nationalism, visited Köstence (Constanţa) in 1895 he discovered his newspaper Tercüman was already in wide circulation. However, it was the poet Mehmet Niyazi who is most credited with spreading nationalist ideas among the Tatars of Dobruja. In the wake of the fall of the Crimean Tatar government, Dobruja became the foremost place of refuge for Tatars from Crimea. Many of these refugees were inspired to join the Prometheus movement in Europe which aimed for the independence of Soviet nationalities. During this period Mustecip Hacı Fazıl (later took the surname Ulkusal) was the leader of community in Dobruja. In 1918, when he was 19 he went to Crimea to teach in Tatar schools and published the first Tatar journal in Dobruja, Emel from 1930 to 1940. He and other nationalists protested Tatar emigration from Dobruja to Turkey, believing resettlement in Crimea was preferable.

In the 1920s Dobruja persisted as the primary destination for refugees escaping the Soviets. The Tatars were relatively free to organize politically and publish journals founded on nationalist ideas. During World War II many Tatars escaped from Crimea and took refugee with Crimean Tatar families in Dobruja who were subsequently punished harshly by Communist Romania. The refugees who attempted escape by sea were attacked by Red Army aircraft, while those who followed land routes through Moldavia managed to reach Dobruja before the Red Army captured and deported most of them to Siberia on May 18, 1944. Necip Hacı Fazıl, the leader of the smuggling committee was executed and his brother Müstecip Hacı Fazıl fled to Turkey.

Developments Post-WWII

In 1940 Southern Dobruja was given to Bulgaria and by 1977 an estimated number of 23,000 Tatars were living in Romania. According to Nermin Eren that number increased to around 40,000 by the 1990s. In 2005 The Democratic Union of Turkish-Muslim Tatars of Romania claimed that there are 50,000 Tatars in Romania, believing the census estimate is artificially low because most Tatars identified themselves as Turks. Nermin Eren also estimated the number of Tatars in Bulgaria to be around 20,000 in 1990s. The Bulgarian sources estimate it to be around 6,000, though they are aware that most Tatars intermarry Turks or identify themselves as Turks. Between 1947-1957 Tatar schools began operating in Romania and in 1955 a special alphabet was created for the Tatar community. In 1990 the Democratic Union of Muslim Tatar-Turks was established. Currently Romania respects the minority rights of Tatars and does not follow any policy of Romanianization.

Notable people

- Murat Iusuf, cleric

- Gelil Eserghep, politician

- Negiat Sali, politician

Subgroups

Crimean Tatars

Crimean Tatars were brought to Dobruja by the Ottomans following the increasing power of the Russians in the region and its annexation of Crimea in 1783. However, after the independence of Romania in 1877-1878, between 80,000 and 100,000 Crimean Tatars moved to Anatolia, a migration which continued afterwards. As such, the number of Tatars in Northern Dobruja decreased from 21% in 1880 to 5.6% in 1912. In 2002, they formed 2.4% of the population.

Nogais

The Nogai component of the Tatar population are not separately enumerated in Romanian censuses. Most have emigrated to Turkey but it is estimated that a few thousand Nogais still live in Dobruja, notably in the town of Mihail Kogălniceanu (Karamurat) and villages of Lumina (Kocali), Valea Dacilor (Hendekkarakuyusu) and Cobadin (Kubadin).

Localities with the highest Tatar population percentage

- Constanța County

- Ciocârlia — 11.18%

- Valu lui Traian — 9.81%

- Techirghiol — 9.22%

- Independența — 8.68%

- Comana — 8.37%

- Medgidia — 8.07%

- 23 August — 7.89%

- Mereni — 7.85%

- Topraisar — 6.48%

- Agigea — 6.39%

- Murfatlar — 5.5%

- Cobadin — 4.86%

- Amzacea — 4.71%

- Grădina — 4.47%

- Tuzla — 4.38%

- Eforie — 3.55%

- Castelu — 3.37%

- Mangalia — 3.25%

- Mihail Kogălniceanu — 3.23%

- Ovidiu — 3.01%

- Lumina — 2.98%

- Limanu — 2.85%

- Siliștea — 2.69%

- Constanța — 2.59%

- Albești — 2.39%

- Bărăganu — 1.7%

- Cumpăna — 1.41%

- Pecineaga — 1.41%

See also

- Democratic Union of Turkish-Muslim Tatars of Romania, a political party representing Tatars in Romania

- Islam in Romania

Notes

- Klaus Roth, Asker Kartarı, (2017), Cultures of Crisis in Southeast Europe: Part 2: Crises Related to Natural Disasters, to Spaces and Places, and to Identities (19) (Ethnologia Balkanica), p. 223

- Stănciugel et al., p.44-46

- Stănciugel et al., p.147

- Romanian Tatars' Site

References

- Robert Stănciugel and Liliana Monica Bălaşa, Dobrogea în Secolele VII-XIX. Evoluţie istorică, Bucharest, 2005