Bulgarians in Turkey

Bulgarians (Turkish: Bulgarlar) form a minority of Turkey. People of Bulgarian ancestry include a large number from the Pomak and a very small number of Orthodox of ethnic Bulgarian origin.

Prior to the ethnic cleansing of Thracian Bulgarians in 1913, the Christian Bulgarians had been more than the Pomaks,[1][2] afterwards Pomak refugees arrived from Greece and Bulgaria. Pomaks are also Muslim and speak a Bulgarian dialect.[3][4][5][6][7] According to Ethnologue at present 300,000 Pomaks in European Turkey speak Bulgarian as mother tongue.[8] It is very hard to estimate the number of Pomaks along with the Turkified Pomaks who live in Turkey, as they have blended into the Turkish society and have been often linguistically and culturally dissimilated.[9] According to Milliyet and Turkish Daily News reports, the number of the Pomaks is 600,000.[9][10] The origin of the Pomaks has been debated,[11][12] but there is an academic consensus that they are descendants of native Bulgarians who converted to Islam during the Ottoman rule of the Balkans;[5][6][7][13][14] nevertheless, most of them currently do not profess Bulgarian identity.

History

| Part of a series on |

| Bulgarians Българи |

|---|

|

| Culture |

|

| By country |

| Subgroups |

| Religion |

|

| Language |

|

| Other |

|

The medieval Bulgarian Empire had active relations with Eastern Thrace before the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans in the 14th–15th century: the area was often part of the Bulgarian state under its stronger rulers from Krum's reign on, such as Simeon I and Ivan Asen II; the city of Edirne (Adrianople, Odrin) was under Bulgarian control a number of times. Bulgarians were sometimes taken captive during Byzantine raids and resettled in Asia Minor (modern Asian Turkey), but their traces are lost in the Middle Ages. As the Balkans were subjugated by the Ottomans, the entirety of the Bulgarian lands fell under Ottoman domination.

It was during the Ottoman rule that a more substantial Bulgarian colony was formed in the imperial capital Istanbul (also known as Constantinople or, in Bulgarian, as Tsarigrad). The so-called "Tsarigrad Bulgarians" (цариградски българи, tsarigradski balgari) were mostly craftsmen (e.g. leatherworkers) and merchants. During the Bulgarian National Revival, Istanbul was a major centre of Bulgarian journalism and enlightenment. Istanbul's St Stephen Church, also known as the Bulgarian Iron Church, was the seat of the Bulgarian Exarchate after 1870. According to some estimates, the Tsarigrad Bulgarians numbered 30–100,000 in the mid-19th century; today, there remains a small colony of 300–400,[16] a small part of the city's Bulgarian community.

A specific part of the Bulgarian population of modern Turkey were the Anatolian Bulgarians, Eastern Orthodox Bulgarians who settled in Ottoman-ruled northwestern Anatolia, possibly in the 18th century, and remained there until 1914.[17]

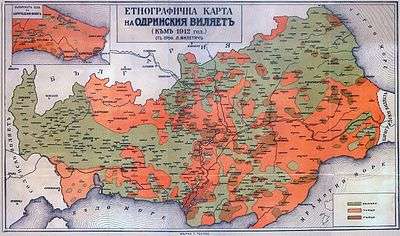

Much more intense was the fate of the Bulgarian population of Eastern Thrace in the Ottoman Province (vilâyet) of Edirne. According to Lyubomir Miletich's detailed study of the province published in 1918, the Bulgarian population of the province (today mostly in Turkey, with smaller parts in Greece and Bulgaria) in 1912 numbered 298,726, of whom 176,554 Exarchists, 24,970 Patriarchists, 1,700 Eastern Catholics and 95,502 Muslims (Pomaks). In the Çorlu and Constantinople regions, Miletich estimates the Bulgarian population at a further 10,000.[18]

After the Balkan Wars of 1912–1913, most of the Bulgarian population was killed or expelled by the Ottomans to Bulgarian-controlled territories. The legal property rights of the expelled Thracian Bulgarians were recognized fully by the Republic of Turkey through the Treaty of Ankara, signed on October 18, 1925, but have been never denied or enforced yet.[19] Almost one century after 1913, the heirs of the Bulgarian refugees have still not been compensated yet.[19] After the Balkan Wars some Turks left Bulgaria and a number of Bulgarians moved from Ottoman Turkey to Bulgaria. Between the Balkan Wars and the First World War there were a series of agreements on exchanges of population between Bulgaria and Turkey.[20]

Present

There remain two Bulgarian Orthodox churches in the city of Edirne: Saint George (dating to 1880) and Saints Constantine and Helena (built in 1869). The Bulgarian churches were reconstructed in the 2000s with the cooperation of Turkey, using mostly Bulgarian state funds. They are both in a good condition today; Saint George also has a Bulgarian library and an ethnographic collection.

In September 2007 Evgeni Kirilov, Bulgarian deputy in the European Parliament, proposed an amendment to the resolution concerning the EU-Turkish relations, which refers to the property of the Thracian Bulgarians and the obligations of Turkish authorities according to the Treaty of Ankara.[19][21][22] In January 2010, Turkish daily Milliyet reported that Bulgarian minister Bozhidar Dimitrov (himself a son of Thracian refugees) talked on a prospect to demand compensation from Turkey in return for the property of expelled Bulgarians.[23] In a response the Turkish foreign minister Ahmet Davutoğlu has underlined that Bulgaria has not filed any official claim and that any such demand needs to be viewed as a whole to also envisage the rights of the two million Turkish refugees from Bulgaria based on the Treaty of Ankara.[24] Bulgarian prime minister Boyko Borisov stated that the Bulgarian government had no prospects for demanding compensation from Turkey and Dimitrov was forced to publicly apologise for his statement.[25]

Notable people

- This list includes people of Bulgarian origin born in what is today Turkey or Bulgarians mainly active in the Republic of Turkey.

- Antim I (1816–1888), first head of the Bulgarian Exarchate (from Kırklareli)

- Alexander Bogoridi (1822–1910), Ottoman statesman of Bulgarian origin (from Istanbul)

- Georgi Valkovich (1833–1892), physician, diplomat and politician (from Edirne)

- Michael Petkov (1850–1921), Eastern Catholic priest (from Edirne)

- Konstantin Bozveliev (1862–1951), socialist politician (from Istanbul)

- Konstantin Kotsev (1926–2007), stage and film actor (from Istanbul)

- Nikola Aslanov (1875–1905), IMARO revolutionary (from Kırklareli)

- Hristo Silyanov (1880–1939), IMARO revolutionary, historian and biographer (from Istanbul)

- G. M. Dimitrov (1903–1972), politician (from Yeniçiftlik)

- Zako Heskija (1922–2006), film director (from Istanbul)

- Hristo Fotev (1934–2002), poet (from Istanbul)

See also

- Minorities in Turkey

- Bulgarian diaspora

- The Destruction of Thracian Bulgarians in 1913

- Bulgaria–Turkey relations

- Turks in Bulgaria

- Anatolian Bulgarians

- Asia Minor Slavs

Gallery

Anatolian Bulgarians in their national costumes

Anatolian Bulgarians in their national costumes

The Bulgarian Church of St George in Edirne

The Bulgarian Church of St George in Edirne%2C_Front.jpg) The Bulgarian Church of Sts Constantine and Helen in Edirne

The Bulgarian Church of Sts Constantine and Helen in Edirne- French ethnographic map of the Balkans by Paul Vidal de la Blache showing the Bulgarian population in Eastern Thrace

See also

- Minorities in Turkey

- Bulgarian diaspora

- The Destruction of Thracian Bulgarians in 1913

- Bulgaria–Turkey relations

- Turks in Bulgaria

References

- Lyubomir Miletich, The Destruction of Thracian Bulgarians in 1913, 1918, p. 291

- Erickson, Edward J. (2003). Defeat in detail: the Ottoman Army in the Balkans, 1912-1913. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-275-97888-4. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- The Balkans, Minorities and States in Conflict (1993), Minority Rights Publication, by Hugh Poulton, p. 111.

- Richard V. Weekes; Muslim peoples: a world ethnographic survey, Volume 1; 1984; p.612

- Raju G. C. Thomas; Yugoslavia unraveled: sovereignty, self-determination, intervention; 2003, p.105

- R. J. Crampton, Bulgaria, 2007, p.8

- Janusz Bugajski, Ethnic politics in Eastern Europe: a guide to nationality policies, organizations, and parties; 1995, p.237

- Gordon, Raymond G. Jr., ed. (2005). "Languages of Turkey (Europe)". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (Fifteenth ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International. ISBN 978-1-55671-159-6.

- "Trial sheds light on shades of Turkey". Hurriyet Daily News and Economic Review. 2008-06-10. Archived from the original on 2011-03-23. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- "Milliyet - Turkified Pomaks in Turkey" (in Turkish). www.milliyet.com.tr. Retrieved 2011-02-08.

- Vemund Aarbakke, The Muslim Minority of Greek Thrace, University of Bergen, Bergen, 2000, pp.5 and 12 (pp. 27 and 34 in the pdf file). "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-04-23. Retrieved 2016-02-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Olga Demetriou, "Prioritizing 'ethnicities': The uncertainty of Pomak-ness in the urban Greek Rhodoppe", in Ethnic and Racial Studies, Vol. 27, No. 1, January 2004, pp.106-107 (pp. 12-13 in the pdf file).

- The Balkans, Minorities and States in Conflict (1993), Minority Rights Publication, by Hugh Poulton, p. 111.

- Richard V. Weekes; Muslim peoples: a world ethnographic survey, Volume 1; 1984; p.612

- Includes both Christian and Muslim Bulgarians.

- Николов, Тони (May 2002). "Българският Цариград чака своя Великден" (in Bulgarian). Двуседмичен вестник на Държавната агенция за българите в чужбина към Министерския съвет. Archived from the original on December 17, 2004. Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- Шишманов, Димитър (2000). Необикновената история на малоазийските българи (in Bulgarian). София: Пони. ISBN 978-954-90585-2-9.

- Милетичъ, Любомир (1918). "Статистиченъ прѣгледъ на българското население въ Одринския виляетъ". Разорението на тракийскитѣ българи презъ 1913 година (in Bulgarian). София: Българска академия на науките. pp. 287–291. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- Terziev, Svetoslav. "The Thracian Bulgarians press Turkey in EU" Archived September 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Sega Newspaper, September 19, 2007. Accessed September 20, 2007. (in Bulgarian)

- R. J. Crampton: "Bulgaria" 2007 pp.431

- "Evgeni Kirilov proposed an amendment about the Thracian Bulgarians in an official report in European Parliament about Turkey", Information Agency Focus, September 18, 2007. Accessed September 20, 2007. (in Bulgarian)

- "The Bulgarian Euro-deputy Evgeni Kirilov proposed an amendment about the Thracian Bulgarians in an official report of the European Parliament about Turkey", Bulgarian National Radio, September 18, 2007. Accessed September 20, 2007. (in Bulgarian)

- Bulgaristan 10 milyar dolar istiyor, Milliyet, January 4, 2010. Accessed January 4, 2010. (in Turkish)

- "Dışişleri Bakanı Davutoğlu, "Yaşananlar tek taraflı göç şeklinde cereyan etmedi" dedi" Archived July 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine "8sutun.com", January 5, 2010. Accessed January 5, 2010 (in Turkish)

- 'Tazminatçı Bakan' özür diledi, Milliyet, January 8, 2010. Accessed January 8, 2010 (in Turkish)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bulgarians in Turkey. |

- Bulgarian embassy in Turkey (in Bulgarian, English, and Turkish)

- Website of the Tsarigrad Bulgarians and the St Stephen Church in Istanbul (in Bulgarian, Russian, and Turkish)

- Website of the Pomaks in Turkey (in Turkish and Bulgarian)

- Bulgarian-Muslims in Turkey