Paulicianism

Paulicians (Old Armenian: Պաւղիկեաններ, Pawłikeanner; Greek: Παυλικιανοί;[1] Arab sources: Baylakānī, al Bayāliqa البيالقة)[2] were a Christian adoptionist sect from Armenia which formed in the 7th century,[3] possibly influenced by the Gnostic movements and the religions of Marcionism and Manichaeism.[4][5] According to medieval Byzantine sources, the group's name was derived from the 3rd century Bishop of Antioch, Paul of Samosata,[6][7] but Paulicianists were often misidentified with Paulianists,[8] while others derived their name from Paul the Apostle,[1][9] hence the identity of the Paul for whom the movement was named is disputed.[4] Constantine-Silvanus is considered to be its founder.[4]

|

|

|

|

|

|

Influenced by |

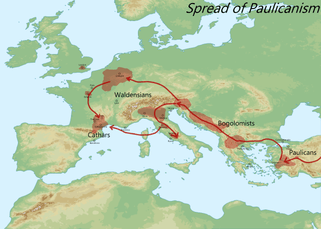

They flourished between 650 and 872 in Armenia and Eastern Anatolia and since then in Theme of Thrace of the Byzantine Empire. They had a widespread political and military influence in Asia Minor, including a temporary independent state in the mid-9th century centered in Tephrike, because of which were continuously persecuted by Byzantine emperors since the mid-7th century. They were also persecuted because of religious reasoning but were not during the periods of Byzantine Iconoclasm or their activity was ignored in exchange for military duties.[9] Between the mid-8th and mid-10th century, Byzantine emperors forcibly moved many Paulician colonies to Philippopolis in Thrace to defend the empire's boundary with the First Bulgarian Empire as well to weaken Paulician influence in the East,[3][4] where they were eventually brought to the Catholic Church at the time of emperor Alexios I Komnenos. In Armenia the movement evolved into Tondrakism,[10] while in Europe influenced the formation of Bogomilism, Catharism and other heretic movements.[4][9] In Europe they are the ancestors of the Roman Catholic Bulgarians, specifically of Banat Bulgarians,[9] and Muslim Bulgarians, specifically the Pomaks.[11]

History

Middle Ages and move to Byzantine Empire

The sources show that most Paulician leaders were Armenians.[12] The founder of the sect is said to have been an Armenian by the name of Constantine,[13] who hailed from Mananalis, a community near Samosata, Syria. He studied the Gospels and Epistles, combined dualistic and Christian doctrines and, upon the basis of the former, vigorously opposed the formalism of the church. Regarding himself as having been called to restore the pure Christianity of Paul the Apostle (of Tarsus), he adopted the name Silvanus (one of Paul's disciples), and about 660, he founded his first congregation at Kibossa, Armenia. Twenty-seven years later, he was arrested by the Imperial authorities, tried for heresy and stoned to death.[13][1] Simeon, the court official who executed the order, was himself converted, and adopting the name Titus, became Constantine’s successor. He was burned to death (the punishment pronounced upon the Manichaeans) in 690.[1]

The adherents of the sect fled, with Paul at their head, to Episparis. He died in 715, leaving two sons, Gegnaesius (whom he had appointed his successor) and Theodore. The latter, giving out that he had received the Holy Ghost, rose against Gegnaesius but was unsuccessful. Gegnaesius was taken to Constantinople, appeared before Leo the Isaurian, was declared innocent of heresy, returned to Episparis, but, fearing danger, went with his adherents to Mananalis. His death (in 745) was the occasion of a division in the sect; Zacharias and Joseph being the leaders of the two parties. The latter had the larger following and was succeeded by Baanies in 775. The sect grew in spite of persecution, receiving additions from some of the iconoclasts.[1] The Paulicians were now divided into the Baanites (the old party) and the Sergites (the reformed sect). Sergius, as the reformed leader, was a zealous and effective converter for his sect; he boasted that he had spread his Gospel "from East to West; from North to South".[14] At the same time the Sergites fought against their rivals and nearly exterminated them.[14]

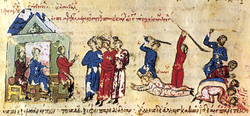

Baanes was supplanted by Sergius-Tychicus in 801, who was very active for thirty-four years. His activity was the occasion of renewed persecutions on the part of Leo the Armenian. Obliged to flee, Sergius and his followers settled at Argaun, in that part of Armenia which was under the control of the Saracens. At the death of Sergius, the control of the sect was divided between several leaders. The Empress Theodora, as regent to her son Michael III, instituted thoroughgoing persecution against the Paulicians throughout Asia Minor,[15] in which 100,000 Paulicians in Byzantine Armenia are said to have lost their lives and all of their property and lands were confiscated by the empire until 843.[16]

Paulicians, under their new leader Karbeas, fled to new areas. They built two cities, Amara and Tephrike (modern Divriği). By 844, at the height of its power, the Paulicians established a principality of the Paulicians centered in Tephrike.[17][18] In 856, Karbeas and his people took refuge with the Arabs in the territory around Tephrike and joined forces with Umar al-Aqta, emir of Melitene (who reigned 835–863).[19] Karbeas was killed in 863 in Michael III's campaign against the Paulicians and possibly was with Umar at Malakopea before the Battle of Lalakaon (863).

Karbeas's successor, Chrysocheres, devastated many cities; in 867, he advanced as far as Ephesus, and he took many priests as prisoners.[20][21] In 868, Emperor Basil I dispatched Petrus Siculus to arrange for their exchange. His sojourn of nine months among the Paulicians gave him an opportunity to collect many facts, which he preserved in his History of the empty and vain heresy of the Manichæans, otherwise called Paulicians. The propositions of peace were not accepted, the war was renewed, and Chrysocheres was killed at Battle of Bathys Ryax (872 or 878).

Rise and fall to power and influence

The power of the Paulicians was broken. Meanwhile, other Paulicians, sectarians but not rebels, lived in communities throughout the Byzantine Empire. Constantine V had already transferred large numbers of them to Thrace.[1] According to Theophanes, part of the Paulicians of Armenia were moved to Thrace, in 747, to strengthen the Bulgarian frontier with a reliable population.[22] By 872, the emperor Basil I conquered their strongholds in Asia Minor (including Tephrike) and killed their leader, and the survivors fled elsewhere in the Empire.[23] One group went to the East to the Byzantine-Arab border - in Armenia, where in the 10th century the Tondrakian sect emerged.[10]

Others were transferred to the Western frontier of the empire. In 885, Byzantine general Nikephoros Phokas the Elder had a military detachment of Paulicians serving in Southern Italy.[10][23] In 970, some 200,000 Paulicians on Byzantine territory were transferred by the emperor John Tzimisces to Philippopolis in Theme of Thrace and,[23] as a reward for their promise to keep back "the Scythians" (in fact Bulgarians), the emperor granted them religious freedom. This was the beginning of a revival of the sect in the West, however the policy of transfer besides limited economical and military benefits for the empire's Western frontier was disastrous to the empire. Not only Paulicians did not assimilate among the natives, but successfully continued the conversion of natives to their heresy. According to Anna Komnene, by the end of 11th century, Philippopolis and its surroundings were entirely inhabited by heretics and they were joined by new groups of Armenians.[23]

According to Annales Barenses,[10] in 1041 several thousand were in the army of Alexios I Komnenos against the Norman Robert Guiscard but, deserting the emperor, many of them (1085) were thrown into prison. By some accounts, Alexios Komnenos is credited with having put an end to the heresy in Europe. During a stay at Philippopolis, Alexios argued with the sect, bringing most, if not all, back to the Church (according to his daughter Anna Komnene in her "Alexiad", XV, 9).[1] For the converts the new city of Alexiopolis was built, opposite Philippopolis. After that episode, Paulicians, as a major force, disappear from history, but as a powerless minority, they would reappear in many later times and places.[1] During the First Crusade some, called as "Publicani", were present in the Muslim army, but sometimes also helped the Crusaders.[10] When Frederick Barbarossa passed near Philippopolis during the Third Crusade, on the contrary to the Greek inhabitants, they welcomed him as a liberator. In 1205 cooperated with Ivan Asen I to turn the city to the Second Bulgarian Empire.[23] The term "Publicani" would be generally used for any heretic, even a political traitor, through Europe, often identified with the Bogomils, Cathars and Albigensians, because of which became a widespread consideration that Paulicians were the ancestors of Western Neo-Manichaean sects.[10]

Modern age and Bulgarian Paulicians

According to the historian Yordan Ivanov, some of the Paulicians were converted to Orthodoxy, and Islam (Pomaks), the rest to the Roman Catholicism during the 16th or 17th century.[9][24] At the end of the 17th century, the Paulician people were still living around Nikopol, Bulgaria and persecuted due to religious reasons by the Ottoman Empire.[9] After the uprising of Chiprovtsi in 1688, a good part of them fled across the Danube and settled in the Banat region. There are still over ten thousand Banat Bulgarian Paulicians in Romania and Serbia today. However, they no longer practice their original religion since they converted to Roman Catholicism. After Bulgaria's liberation from Ottoman rule in 1878, a number of Banat Bulgarians resettled in the northern part of Bulgaria.

In Russia, after the war of 1828–29, Paulician communities could still be found in the part of Armenia occupied by the Russians. Documents of their professions of faith and disputations with the Gregorian bishop about 1837 (Key of Truth, xxiii–xxviii) were later published by Frederick Cornwallis Conybeare. It is with Conybeare publications of the Paulicians disputations and The Key of Truth that Conybeare based his depiction of the Paulicians as simple, godly folk who had kept an earlier Adoptionistic form of Christianity.[1]

Doctrines

Little is known of the tenets of the Paulicians except for the reports of opponents and a few fragments of Sergius' letters they have preserved. Some argue that their system was dualistic,[25] while others add that it was also adoptionist in nature.[3][10] They might have also been nontrinitarian, as Conybeare, in his edition of the Paulician manual The Key of Truth, concluded that "The word Trinity is nowhere used, and was almost certainly rejected as being unscriptural."[26] In dualistic theology, there are two principles, two kingdoms. The Evil Spirit is the demiurge, the author and lord of the present visible world; the Good Spirit, of the future world.[4][6]

The Paulicians accepted the four Gospels (especially of Luke);[4] fourteen Epistles of Paul; the three Epistles of John; the epistles of James and Jude; and an Epistle to the Laodiceans, which they professed to have. They rejected the First Epistle of Peter and the whole Tanakh,[4] also known as the Hebrew Bible or Old Testament, as well as the Orthodox-Catholic title Theotokos ("Mother of God"), and they refused all veneration of Mary.[6] They believed that Christ came down from heaven to emancipate humans from the body and from the world. Their places of worship they called "places of prayer", small rooms in modest houses.[9] Although they had ascetic tendencies, they made no distinction in foods and practiced marriage. They called themselves "Good Christians" and called other Christians "Romanists".[27] Due to iconoclasm they rejected the Christian cross, rites, sacraments, the worship, and the hierarchy of the established Church,[4][9] because of which Edward Gibbon considered them as "worthy precursors of Reformation".[10]

Although the Paulicians have been traditionally and overreachingly labeled as Manichaeans, because of identification with Cathars and Waldensians as their ancestors,[10][28] as Photius, Petrus Siculus, and many modern authors have held, they were not a branch of them.[29] Mosheim was the first to give a serious criticism of identification with Manichaeans, as although both sects were dualistic, the Paulicians differed on several points,[10] and themselves rejected the doctrine of the prophet Mani.[10] Gieseler and Neander, with more probability, derived the sect from Marcionism, considering them as descendants of a dualistic sect reformed to become closer to Early Christianity yet unable to be freed from Gnosticism.[10] Others doubted the resemblance and relation to both Manichaeism and Marcionism.[10] Mosheim, Gibbon, Muratori, Gilles Quispel and others regard the Paulicians as the forerunners of Bogomilism, Catharism and other "heretic" sects in the West.[4][10] By the mid-19th century the mainstream theory was to be a non-Manichaean, dualistic Gnostic doctrine with substantial elements of Early Christianity, closest to Marcionism, which influenced emerging anti-Catholic groups in Western Europe.[10] However, it was primarily based on Greek sources, as later published Armenian sources did indicate some other elements, but the general opinion did not change. Conybeare studying Armenian sources concluded that they were survivors of Early Adoptionist Christianity in Armenia, and not dualism and Gnosticism, which consideration Garsoïan related to earlier by Chel'tsov which argued their doctrine was not static yet showed marked evolution. Garsoïan in a comprehensive study of both Greek and Armenian sources confirmed such conclusions, and that the new Byzantine Paulicianism independently manifested features of Docetism and dualism because of which could be called as Neo-Paulicianism.[30] Another theory was held by Soviet scholars since 1940s who instead of theological origin rather argued a proletarian revolt which was expressed in the theological sense. Such an approach is supported by both Greek and Armenian sources, but it is very limited in explanation and description of the sect.[10]

The Paulicians were branded as Jews, Mohammedans, Arians, and Manichæans; it is likely that their opponents employed the "pejorative" appellations merely as terms of abuse.[31] They called themselves Christians,[32] or "True Believers".[2] Armenians always formed the majority in the provinces where the Paulicians were most influential and successful in spreading their doctrines.[12]

See also

- Albigensians

- Banat Bulgarians

- Banat Bulgarian dialect

- Bogomilism

- Edmund Hamer Broadbent - The Pilgrim Church

- Novgorod Codex

- Paulician dialect

- Pavlikeni

- Restorationism

- Roman Catholicism in Bulgaria

- Tondrakians

Further reading

- Herzog, "Paulicians," Philip Schaff, ed., A Religious Encyclopaedia or Dictionary of Biblical, Historical, Doctrinal, and Practical Theology, 3rd edn, Vol. 2. Toronto, New York & London: Funk & Wagnalls Company, 1894. pp. 1776–1777

- Nikoghayos Adontz: Samuel l'Armenien, Roi des Bulgares. Bruxelles, Palais des academies, 1938.

- (in Armenian) Hrach Bartikyan, Quellen zum Studium der Geschichte der paulikianischen Bewegung, Eriwan 1961.

- The Key of Truth, A Manual of the Paulician Church of Armenia, edited and translated by F. C. Conybeare, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1898.

- S. B. Dadoyan: The Fatimid Armenians: Cultural and Political Interaction in the Near East, Islamic History and Civilization, Studies and Texts 18. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 1997, Pp. 214.

- Nina G. Garsoian: The Paulician Heresy. A Study in the Origin and Development of Paulicianism in Armenia and the Eastern Provinces of the Byzantine Empire. Publications in Near and Middle East Studies. Columbia University, Series A 6. The Hague: Mouton, 1967, 296 pp.

- Nina G. Garsoian: Armenia between Byzantium and the Sasanians, London: Variorum Reprints, 1985, Pp. 340.

- Newman, A.H. (1951). "Paulicians". In Samuel Macaulay Jackson (ed.). New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. VIII. Baker Book House, Michigan. pp. 417–418.

- Vahan M. Kurkjian: A History of Armenia (Chapter 37, The Paulikians and the Tondrakians), New York, 1959, 526 pp.

- A. Lombard: Pauliciens, Bulgares et Bons-hommes, Geneva 1879

- Vrej Nersessian: The Tondrakian Movement, Princeton Theological Monograph Series, Pickwick Publications, Allison Park, Pennsylvania, 1948, Pp. 145.

- Edward Gibbon: 'History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire' (Chapter LIV).

References

- "Catholic Encyclopedia: Paulicians". New Advent. 1 February 1911. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- Nersessian, Vrej (1998). The Tondrakian Movement: Religious Movements in the Armenian Church from the 4th to the 10th Centuries. London: RoutledgeCurzon. p. 13. ISBN 0-900707-92-5.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Michigan: University of Michigan Press. pp. 173, 299. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- "Paulician". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Wilson, Joseph (2009). "The Life of the Saint and the Animal: Asian Religious Influence in the Medieval Christian West". The Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture. 3 (2): 169–194. doi:10.1558/jsrnc.v3i2.169. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- (in Armenian) Melik-Bakhshyan, Stepan. «Պավլիկյան շարժում» (The Paulician movement). Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia. vol. ix. Yerevan, Armenian SSR: Armenian Academy of Sciences, 1983, pp. 140-141.

- Nersessian, Vrej (1998). The Tondrakian Movement: Religious Movements in the Armenian Church from the 4th to the 10th Centuries. London: RoutledgeCurzon. pp. 14–15. ISBN 0-900707-92-5.

- Peter L'Huillier (1996). The Church of the Ancient Councils: The Disciplinary Work of the First Four Ecumenical Councils. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-0-88141-007-5.

- Nikolin, Svetlana (2008). "Pavlikijani ili banatski Bugari" [Paulicians or Banat Bulgarians]. XXI Vek (in Serbo-Croatian). 3: 15–16. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Garsoïan, Nina G. (1967). The Paulician heresy: a study of the origin and development of Paulicianism in Armenia and the Eastern Provinces of the Byzantine empire. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 13–26. ISBN 978-3-11-134452-2.

- Edouard Selian. "The Descendants of Paulicians: the Pomaks, Catholics, and Orthodox". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Nersessian, Vrej: The Tondrakian Movement, Princeton Theological Monograph Series, Pickwick Publications, Allison Park, Pennsylvania, 1948, p.53.

- "Constantine-Silvanus". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- Petrus Siculus, "Historia Manichaeorum", op. cit., 45

- Leon Arpee. A History of Armenian Christianity. The Armenian Missionary Association of America, New York, 1946, p. 107.

- Norwich, John Julius: A Short History of Byzantium Knopf, New York, 1997, page 140

- "Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Μείζονος Ελληνισμού, Μ. Ασία". Asiaminor.ehw.gr. Retrieved 2016-09-25.

- Panos, Masis (24 April 2011). "Understanding our past: The Paulicians: A timeline & map". Understanding-our-past.blogspot.com. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- Digenis Akritas: The Two-Blooded Border Lord. Trans. Denison B. Hull. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1972

- "Paulicians". MedievalChurch.org.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- "The Encyclopedia of Thelema & Magick | Bogomils". Thelemapedia.org. 15 July 2005. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- Nersessian, Vrej: The Tondrakian Movement, Princeton Theological Monograph Series, Pickwick Publications, Allison Park, Pennsylvania, 1948, p.51.

- Charanis, Peter (1961). "The Transfer of Population as a Policy in the Byzantine Empire". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 3 (2): 142, 144–152. JSTOR 177624.

- "Йордан Иванов. Богомилски книги и легенди" (in Bulgarian). Jordan Ivanov. Bogomil Books and Legends, Sofia. 1925. p. 36.

- Treadgold, Warren (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford: University of Stanford Press. p. 448. ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.

- The Key of Truth. A Manual of the Paulician Church of Armenia. Page xxxv Frederick Cornwallis Conybeare "The context implies that the Paulicians of Khnus had objected as against those who deified Jesus that a circumcised man could not be God. ... The word Trinity is nowhere used, and was almost certainly rejected as being unscriptural."

- Maoosa, Matti (1987). Extremist Shiites: The Ghulat Sects. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-815-62411-5.

- "Cyclopædia, or, An universal dictionary of arts and sciences : Arterial - attaching". digicoll.library.wisc.edu. Retrieved 2017-03-04.

- Charles L. Vertanes. The Rise of the Paulician Movement in Armenia and its Impact on Medieval Europe. Journal of Armenian Studies, NAASR, Cambridge, 1985-86, vol.II, No.2, p. 3-27.

- Toumanoff, Cyril (1 February 1969). "The Paulician Heresy: A Study of the Origin and Development of Paulicianism in Armenia and the Eastern Provinces of the Byzantine Empire (Review)". The American Historical Review. 74 (3): 961–962. doi:10.1086/ahr/74.3.961. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- John Goulter Dowling. A letter to S. R. Maitland. On the Opinions of the Paulicians, London, 1835. p. 50.

- John Goulter Dowling. A letter to S. R. Maitland. On the Opinions of the Paulicians, London, 1835. p. 16.

External links

- Leon Arpee. Armenian Paulicianism and the Key of Truth. The American Journal of Theology, Chicago, 1906, vol. £, p. 267-285

- Gibbon, Edward; Milman, Henry Hart, "The Paulican Heresy", in Widger, David (ed.), The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, X

- Full text of "The key of truth, a manual of the Paulician church of Armenia