Romanians of Serbia

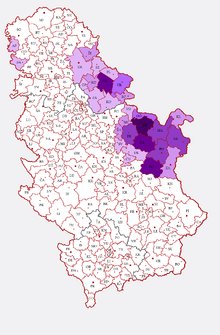

Romanians (Romanian: Românii din Serbia, Serbian: Румуни у Србији, romanized: Rumuni u Srbiji) are a recognised national minority in Serbia. The total number of declared Romanians according to the 2011 census[1] was 29,332, while 35,330 people declared themselves Vlachs; there are differing views among some of the Vlachs over they should be regarded as Romanians or as members of a distinctive nationality. Declared Romanians are mostly concentrated in Banat, while declared Vlachs are mostly concentrated in Eastern Serbia.

Flag of the National Council of Romanian minority in Serbia | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 29,332 (2011) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Banat | |

| Languages | |

| Romanian, Vlach | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Romanian Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Evangelical Christian |

Demographics

Of the total number of 29,332 declared Romanians in the 2011 census, 22,353 live in Banat and 1,826 live in Eastern Serbia. Of the total number of 35,330 declared Vlachs, 32,805 live in Eastern Serbia, and 134 in Banat. The largest concentration of Romanians in Banat are to be found in the municipalities of Alibunar (24.1%) and Vršac (10.4%).

| Year | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1856 | 104,343 Romanians | 16.81% |

| 1859 | 122,593 Romanians | 14.47% |

| 1866 | 127,545 Romanians | 10.5% |

| 1884 | 149,727 Romanians | 7.87% |

| 1895 | 159,000 Romanians | 6.43% |

| 1921 | 224,746 Romanians | 4.7% |

| 1931 | 130,635 Romanians | 2.3% |

| 1948 | 63,130 Romanians | 0.91% |

| 1953 | 59,705 Romanians; 28,407 Vlachs | 0.85%; 0.4% |

| 1961 | 59,505 Romanians; 1,330 Vlachs | 0.78%; 0.02% |

| 1971 | 57,419 Romanians; 14,724 Vlachs | 0.68%; 0.17% |

| 1981 | 53,693 Romanians; 25,596 Vlachs | 0.58%; 0.27% |

| 1991 | 42,331 Romanians; 17,807 Vlachs | 0.43%; 0.18% |

| 2002 | 34,576 Romanians; 40,054 Vlachs | 0.46%; 0.53% |

| 2011 | 29,332 Romanians; 35,330 Vlachs | 0.41%; 0.49% |

Banat

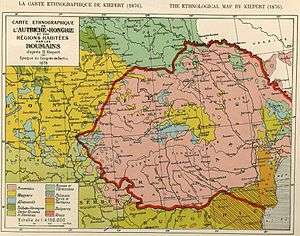

After World War I, the Treaty of Versailles, which defined the borders between Romania and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, left a Romanian minority of 75,223 people (1910 census in Vojvodina) inside the borders of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. In the 1921 census in Vojvodina, Romanian-speakers numbered 65,197 people. According to the 2011 census, there were 42,391 Romanians in Vojvodina (2.2% of the population of Vojvodina).

Settlements in the Serbian Banat (Vojvodina) with a Romanian majority or plurality (2002 census data):

- Uzdin (Kovačica municipality),

- Jankov Most (Zrenjanin municipality),

- Torak (Žitište municipality),

- Lokve (Alibunar municipality),

- Nikolinci (Alibunar municipality),

- Seleuš (Alibunar municipality),

- Grebenac (Bela Crkva municipality),

- Barice (Plandište), (Plandište municipality),

- Straža (Vršac municipality),

- Orešac (Vršac municipality),

- Vojvodinci (Vršac municipality),

- Kuštilj (Vršac municipality),

- Jablanka (Vršac municipality),

- Sočica (Vršac municipality),

- Mesić (Vršac municipality),

- Markovac (Vršac municipality),

- Mali Žam (Vršac municipality),

- Gamzigrad (Zaječar municipality)

- Malo Središte (Vršac municipality),

- Ritiševo (Vršac municipality).

Eastern Serbia

It is likely that a part of the Vlachs can trace their ancient roots to this region. The present geographic location of the Vlachs is near a former location in the medieval Second Bulgarian Empire (also called the Empire of Vlachs and Bulgars)[2] of the Asens, suggesting their continuity in the area. In addition a Vlach population in the regions around Braničevo (near the ancient Roman city of Viminacium) is attested by 15th century Ottoman defters (tax records). The modern Vlachs occupy the same area where in antiquity the Romans had a strong presence for many centuries: Viminacium and Felix Romuliana.

However, some of the Vlachs of north-eastern parts of Central Serbia were settled there from regions north of the Danube by the Habsburgs at the beginning of the 18th century. The origins of these Vlachs are indicated by their own self-designations: "Ungureani (Ungureni)" (serb. Ungurjani), i.e. those who came from Hungary (that is, Banat and Transylvania) and "Ţărani" (serb. Carani), who are either an autochthonic population of the region (their name means "people of the country" or "countrymen"), either they came from Wallachia (Romanian: Ţara Românească – "Romanian State").

The area roughly defined by the Morava, the Danube and the Timok rivers where most of the Vlachs live became part of modern Serbia. Until 1833 the eastern Serbian border was the Homolje-Mountains (the slopes of the Serbian Carpathians) and the state had no common border with Walachia. Prior to that, the land was part of the Ottoman Empire (Pashaluk of Vidin and Pashaluk of Smederevo) and Habsburg Monarchy (Governorate of Serbia).

The second wave of Vlachs from present-day Romania came in the middle of the 19th century. In 1835 feudalism was fully abolished in the Principality of Serbia and smaller groups from Wallachia came there to enjoy the status of free peasants. (1856: 104,343 Romanians lived in Serbia, 1859: 122,593 Romanians)

According to the Treaty of Neuilly-sur-Seine from 1919, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes annexed from Bulgaria also a small section along the Timok River in the municipality and District of Zaječar, composed by 8 localities (7 populated by Romanians and 1 populated by Bulgarians).[3]

.jpg)

History

As Daco-Romanian-speakers, the Vlachs have a connection to the Roman heritage in Serbia. Following Roman withdrawal from the province of Dacia at the end of the 3rd century, the name of the Roman region was changed to Dacia Aureliana, and (later Dacia Ripensis) spread over most of what is now called Serbia and Bulgaria, and an undetermined number of Romanized Dacians (Carpi) were settled there.[4][5] Strong Roman presence in the region persisted through the end of Justinian's reign in the 6th century.[6]

The region where Vlachs predominantly live later on was part of the Second Bulgarian Empire, whose first rulers, the Asens, are considered Vlach.[7] King Stephen Uroš II Milutin of Serbia had most of Timok after his conquering of rival King Stephen Dragutin's lands. The chroniclers of the crusaders describe meeting Vlachs in the 12th and 13th century in various parts of modern Serbia.[8][9] Serbian documents from the 13th and 14th century mention Vlachs, including Emperor Dušan the Mighty, in his prohibition of intermarriage between Serbs and Vlachs.[8][9] 14th and 15th century Romanian (Wallachian) rulers built churches in NE Serbia.[10] 15th century Turkish tax records (defters) list Vlachs in the region of Braničevo in NE Serbia, near the ancient Roman municipium and colonia of Viminacium.[11]

Starting in the early 18th century NE Serbia was settled by Romanians (then known by their international exonym as Vlachs) from Banat, parts of Transylvania, and Oltenia (Lesser Walachia).[8] These are the Ungureni (Ungurjani), Munteni (Munćani) and Bufeni (Bufani). Today about three quarters of the Vlach population speak the Ungurean subdialect. In the 19th century other groups of Romanians, originating in Oltenia (Lesser Wallachia), also settled south of the Danube.[12] These are the Ţărani (Carani), who form some 25% of the modern population. The very name Ţărani indicates their origin in Ţara Româneasca, i.e., "The Romanian Land," Wallachia and Oltenia. From the 15th through the 18th centuries large numbers of Serbs also migrated across the Danube, but in the opposite direction, to both Banat and Ţara Româneasca. Significant migration ended with the establishment of the kingdoms of Serbia and Rumania, respectively, in the second half of the 19th century.

The lack of detailed census records and the linguistic effects of the Ungureni and Ţărani on the entire Vlach population make it difficult to determine what fraction of the present Vlachs can trace their origins directly to the ancient south-of-the-Danube Vlachs. The Vlachs of NE Serbia form a contiguous linguistic, cultural and historic group with the Vlachs in the region of Vidin in Bulgaria, as well as the Romanians of Banat and Oltenia (Lesser Wallachia).

In a Romanian-Yugoslav agreement of November 4, 2002, the Yugoslav authorities agreed to recognize the Romanian identity of the Vlach population in Central Serbia,[13] but the agreement was not implemented.[14] In April 2005, many deputies from the Council of Europe protested against the position of this population in Serbian society.[15] In August 2007, they were officially recognized as a national minority, and their language was recognized as Romanian.[16]

Culture

In Vojvodina, Romanian enjoys the status of official language and Romanians in this province receive a wide range of minority rights, including access to state-funded media and education in their native language. Most of the Romanians of Serbia are Eastern Orthodox by faith, belonging to the Romanian Orthodox Church (Romanians in Vojvodina) and Serbian Orthodox Church (Vlachs of Central Serbia). The relative isolation of the Vlachs has permitted the survival of various pre-Christian religious rites that are frowned upon by the Orthodox Church.

The language spoken by one major group of Vlachs is similar to the Oltenian variety spoken in Romania while that of the other major group is similar to the Romanian variety of Banat.

Notable people

- Vasko Popa (1922–1991), a Serbian poet of Romanian descent.

- Emil Petrovici (1899–1958), linguist

- Slavco Almăjan (b. 1940), poet

- Ionel Stoiţ (b. 1952), poet

- Bojan Aleksandrović (b. 1977), priest

- Raimond Gaita (b. 1946), German-born Australian philosopher and author of Romanian descent.

See also

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-01-14. Retrieved 2016-01-11.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- According to Encyclopaedia Britannica the state is also called "The Vlach-Bulgarian Empire"

- Tribalia

- Alaric Watson, Aurelian and the Third Century, Routledge, 1999.

- https://books.google.com/books?id=ukf-lEYl3FUC&pg=PR3&dq=Alaric+Watson,+Aurelian+and+the+Third+Century,+Routledge,+1999.&hl=en&ei=vDOVTs3eKeqK4gTBtqCYCA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CDYQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Roman%20withdrawal%20&f=false page 157

- William Rosen, Justinian's Flea: Plague, Empire, and the Birth of Europe, Viking Adult, 2007.

- Wolff, Robert Lee Wolff, The Second Bulgarian Empire: Its Origin and History to 1204, SpeculumVolume 24, Issue 2 , 1949.

- (in Croatian)Zef Mirdita, Vlasi u historiografiji, Hrvatski institut za povijest, Zagreb 2004.

- Noel Malcolm, Kosovo, A short History, University Press, NY, 1999.

- (in German) Felix Kanitz, Serbien, Leipzig, 1868.

- Noel Malcolm, Bosnia: A short History, University Press, NY, 1994.

- (in Serbian) Kosta Jovanovic, Negotinska Krajina i Kljuc, Belgrade, 1940

- Adevărul, 6 Noiembrie 2002: Prin acordul privind minoritatile, semnat, luni, la Belgrad, de catre presedintii Ion Iliescu si Voislav Kostunita, statul iugoslav recunoaste dreptul apartenentei la minoritatea romaneasca din Iugoslavia al celor aproape 120.000 de vlahi (cifra neoficiala), care traiesc in Valea Timocului, in Serbia de Rasarit.

- Curierul Naţional, 25 ianuarie 2003: Chiar si acordul dintre presedintii Ion Iliescu si Voislav Kostunita, semnat la sfarsitul anului trecut, nu este respectat, in ceea ce priveste minoritatile, deoarece locuitorii din Valea Timocului, numiti vlahi, nu sunt recunoscuti ca minoritari, ci doar „grup etnic“.

- Parliamentary Assembly, 28 April 2005 Archived 30 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine: Deeply concerned over the cultural situation of the so-called “Vlach” Romanians dwelling in 154 ethnic Romanian localities 48 localities of mixed ethnic make-up between the Danube, Timok and Morava Rivers who since 1833 have been unable to enjoy ethnic rights in schools and churches

- România Liberă, 16 August 2007 Archived 26 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine: Romanii din Valea Timocului, cunoscuti drept vlahi, au obtinut recunoasterea statutului de minoritate nationala. Decizia guvernului de la Belgrad inseamna, printre altele, ca limba romana ar putea fi predata in premiera in scolile din Serbia unde romanii timoceni sunt majoritari, transmite BBC, preluat de Rompres.

Sources

- Popi, Gligor. (2003) "Românii din Banatul sârbesc", Magazin Istoric, no. 8/2003.

External links

- The Romanian Community in Serbia

- The Romanians in Vojvodina

- The Romanians in Serbia and Bulgaria

- Romanians in Serbia

- Respect for the rights of the Timok Romanians (Eastern Serbia)

- Vesna Čekić (2002-10-24). "Živeti zajedno – Manjinske nacionalne zajednice u Vojvodini: Rumuni" (in Serbian). Dnevnik. Archived from the original on February 14, 2012. Retrieved 2007-05-18.

- MP3 recordings of Vlach speech

- Maps of Vlachs in north-east Serbia

- The Vlachs in Yugoslavia and their magic

- Report on the State of Human Rights of Rumanians and Vlachs in Serbia

- Românii din Serbia, Ion Florentin Dobrescu

- The situation of national minorities in Vojvodina and of the Romanian ethnic minority in Serbia, 2008 report from the Council of Europe (archive version)