Hungarians in Serbia

Hungarians (Serbian: Мађари, romanized: Mađari) are the second largest ethnic group in Serbia if not counting Kosovo.[a] According to the 2011 census, there are 253,899 ethnic Hungarians composing 3.5% of the population of Serbia.[1] The majority of them live in the northern province of Vojvodina, where they number 251,136 or 13% of the population of the province. Most Hungarians in Serbia are Roman Catholics by faith, while smaller numbers of them are Protestant (mostly Calvinist). Hungarian is listed as one of the six official languages of Vojvodina, an autonomous province which traditionally fosters multilingualism, multiculturalism and multiconfessionalism.[2]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 253,899 (2011)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 251,136 | |

| Languages | |

| Hungarian, Serbian | |

| Religion | |

| predominantly Catholicism, minority Protestantism | |

History

Parts of the Vojvodina region were included in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary in the 10th century, and Hungarians then began to settle in the region, which before that time was mostly populated by West Slavs. During Hungarian administration, Hungarians formed the largest part of the population in northern parts of the region, while southern parts were populated by sizable Slavic peoples. Following the Ottoman conquest and inclusion of Vojvodina into Ottoman Empire in the 16th century, most Hungarians fled the region. During Ottoman rule, Vojvodina region was mostly populated by Serbs and Muslim Slavs (Great Migrations of the Serbs). New Hungarian settlers started to come to the region with the establishment of the Habsburg administration at the beginning of the 18th century, mostly after the Peace of Passarowitz (Požarevac).

Settlement

Count Imre Csáky settled Hungarians in his possessions in Bačka in 1712. In 1745, Hungarian colonists settled in Senta, in 1750 in Topola, in 1752 in Doroslovo, in 1772 in Bogojevo, in 1760 in Stara Kanjiža, in 1764 in Iđoš, in 1767 in Petrovo Selo, in 1776 in Martonoš, in 1786 in Pačir and Ostojićevo, in 1787 in Piroš, and in 1789 in Feketić. Between 1782 and 1786, Hungarians settled in Crvenka and Stara Moravica, and in 1794 in Kula.

Hungarians of Roman Catholic faith originated mostly from Transdanubia, while those of Protestant faith originated mostly from Alföld. Between 1751 and 1753, Hungarians settled in Mol and Ada (Those originated mostly from Szeged and Jászság). In 1764–1767, Hungarians settled in Subotica, Bajmok and Čantavir, and in 1770 again in Kanjiža, Mol, Ada and Petrovo Selo, as well as in Feldvarac, Sentomaš and Turija.

In Banat, the settling of Hungarians started later. In 1784 Hungarians settled in Padej and Nakovo, in 1776 in Torda, in 1786 in Donji Itebej, in 1796 in Beodra and Čoka, in 1782 in Monoštor, in 1798 in Mađarska Crnja, in 1773 in Krstur and Majdan, in 1774 in Debeljača, in 1755–1760 in Bečkerek, and in 1766 in Vršac. In 1790, 14 Hungarian families from Transylvania settled in Banat.

In the 19th century, the Hungarian expansion increased. From the beginning of the century, the Hungarian individuals and small groups of settlers from Alföld constantly immigrating to Bačka. In the first half of the 19th century larger and smaller groups of the colonists settled in Mol (in 1805), as well as in Feldvarac, Temerin and Novi Sad (in 1806). In 1884, Hungarian colonists settled in Šajkaška and in Mali Stapar near Sombor. In 1889, Hungarians were settled in Svilojevo near Apatin and in 1892 in Gomboš, while another group settled in Gomboš in 1898. Many Hungarian settlers from Gomboš moved to Bačka Palanka. After the abolishment of the Military Frontier, Hungarian colonists were settled in Potisje, Čurug, Žabalj, Šajkaški Sveti Ivan, Titel and Mošorin. In 1883 around 1,000 Székely Hungarians settled in Kula, Stara Kanjiža, Stari Bečej and Titel.

In 1800, smaller groups of Hungarian colonists from Transdanubia settled in Čoka, while in the same time colonists from Csanád and Csongrád counties settled in area around Itebej and Crnja, where they at first lived in scattered small settlements, and later they formed one single settlement – Mađarska Crnja. In 1824, one group of colonists from Čestereg also settled in Mađarska Crnja. In 1829 Hungarians settled in Mokrin, and in 1880 an even larger number of Hungarians settled in this municipality. In 1804, Hungarian colonists from Csongrád county settled in Firiđhaza (which was then joined with Turska Kanjiža), as well as in Sajan and Torda. Even a larger group of Hungarians from Csongrád settled in 1804 in Debeljača. In 1817–1818 Hungarians settled in Veliki Bikač, and in 1820–1840 smaller groups of Hungarians settled in Vranjevo. In 1826, colonists from Jászság and Kunság settled in Arač near Beodra. In 1830, Hungarians from Alföld settled in Veliki Lec, in 1831 in Ostojićevo, in 1832 in Malenčino Selo near Veliki Gaj, in 1839 and 1870 in Padej, in 1840 in Jermenovci and Mađarski Sentmihalj, in 1840–1841 in Dušanovac, in 1841 in Hetin, in 1859 in Sanad, in 1869 in Đurđevo (later moved to Skorenovac), and in 1890 in Gornja Mužlja. In 1883-1886, Székely Hungarians from Bukovina were settled in Vojlovica, Skorenovac, Ivanovo and Đurđevo. Total number of Székely colonists was 3,520.

The first Hungarian settlers in the southern region of Srem moved there during the 1860s from neighbouring counties, especially from Bačka.

According to the 1900 census, the Hungarians were the largest ethnic group in the Bács-Bodrog County and made up 42.7% in the population (the second largest were Germans with 25.1%, and the third largest group were Serbs with 18.2%). The Hungarians were third largest group in the Torontál County (West Banat) with 18.8% (after Serbs with 31.5% and Germans with 30,2%).[3] In the next census, in 1910, the Hungarians were the largest group in the Bács-Bodrog County with 44,8% in the population (followed by Germans with 23.5% and Serbs with 17.9%), and the third largest in the Torontál County with 20.9% (Serbs with 32.5%, Germans with 26.9%).[3]

The new temporary borders established in 1918 and permanent ones defined by the Treaty of Trianon in 1920 put an end to Hungarian immigration. After World War I, present-day Vojvodina was included into the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (later known as the Kingdom of Yugoslavia) and many Hungarians of Vojvodina wanted to live in the post-Trianon Hungarian state, thus, some of them immigrated to Hungary, which was a destination for several emigration waves of Hungarians from Vojvodina. The interwar period was generally marked by a stagnation of the Hungarian population. During these times, they numbered around 363,000 (1921 census) – 376,000 (1931 census) and they constituted about 23-24% of the entire population of Vojvodina. The outbreak of the Second World War caused some changes in population numbers, but more importantly it created tensions between the Hungarian and Serb communities.

World War II

With the onset of World War II, the Hungarian-Serb relations were low. Nazi Germany, in accordance to its "Operation Punishment" plan, invaded Yugoslavia, and subsequently, Axis Hungarian forces occupied Bačka. This region was annexed by Hungary, and it was settled by new Hungarian settlers, at which time number of Hungarians in the area grew considerably, while in the same time many Serbs were expelled from Bačka. The brutal conduct of the Axis Hungarian occupying forces, including the Hungarian army and Royal Hungarian Gendarmes, has polarized both Hungarian and Serb communities. Under the Axis Hungarian authority, 19,573 people were killed in Bačka, of which the majority of victims were of Serb, Jewish and Romani origin.

Although most of the local Hungarian population supported Hungarian Axis authorities, some other local Hungarians opposed Axis rule and fought against it together with Serbs and other peoples of Vojvodina in the Partisan resistance movement organized by the Communist Party. In some places of Vojvodina (Bačka Topola, Senta), most of the members of the communist party were ethnic Hungarians. In Subotica, the party secretary and most of the leadership were either ethnic Hungarians or Hungarian-speaking Jews. In the Bačka Topola municipality, 95% of communists were ethnic Hungarians. One of the leaders of the partisan resistance movement in Vojvodina was Erne Kiš, ethnic Hungarian, who was captured by the Axis authorities, sentenced to death by the court in Szeged and executed.

Among the other actions of the resistance movement, the first corn stacks were burned near Futog by five communists, of whom two were ethnic Hungarians – brothers Antal Nemet and Đerđ Nemet. Antal was killed there, together with his Serb comrade, in the fighting against gendarmes, while his brother was captured and killed in Novi Sad because he refused to reveal any information about resistance movement. The corn stacks were soon also burned near Subotica. The communists that burned these corn stacks were arrested, tortured and sent to court. Two of them were sentenced to death (Ferenc Hegediš and Jožef Liht), while five other were sentenced to prison (because they were not adult).

The Axis authorities also arrested sizable number of Hungarian communists in Bačka Topola, Čantavir, Senta, Subotica and Novi Sad. Many of them were sent to the investigation centre in Bačka Topola, where part of them was killed, while some committed suicide. Among those Hungarian communists who were sent to the centre were Otmar Majer, Đula Varga, Pal Karas and Janoš Koči. Because of the size of the communist movement among Hungarians, new investigation centres were opened in Čantavir, Senta, Ada and Subotica. In the investigation centre in Subotica, almost 1,000 people were tortured, and part of them killed, among whom were Maćaš Vuković and Daniel Sabo. Among those communists sentenced to death were Otmar Majer, Rokuš Šimoković and Ištvan Lukač from Subotica, Peter Molnar from Senta, as well as Đula Varga, Rudi Klaus, Pal Karas and Janoš Koči from Novi Sad. In Petrovo Selo, Mihalj Šamu was killed during his attempt to escape. These actions of the Axis authorities were a hard strike on the resistance movement in Bačka, especially on its Hungarian component. The Hungarian component of the resistance movement was struck so hard that it could not recover until the end of the war.

In 1944, the Soviet Red Army and the Yugoslav partisan] took control of Vojvodina, and new communist authorities initiated purges against one part of local population that either collaborated with the Axis authorities or was viewed as a threat to the new regime (see: Communist purges in Serbia in 1944–1945). During this time, Partisans brutally massacred about 40,000 Hungarian civilians.[4] In October 1944 3,000 inhabitants of Hungarian nationality in Srbobran were executed by the Serbian communist partisans from the village of 18,000 inhabitants.

In Bečej killing of the Hungarians began on 9 October 1944. In the city of Sombor in October 1944 the murdering of the Hungarians started at once on the basis of the death-list previously made. The Hungarians were taken to the Palace of Kronich. Next to the race-course the common graves were dug in which 2,500 Hungarians were buried. Several other common graves can be found in the outside districts of the city. The inhabitants of the Hungarian city were fully exterminated. In total 5,650 Hungarians were executed. A Soviet officer in Temerin prevented the extirpation of the whole Hungarian population of the village. Hungarian human loss of the village was 480 people. During the first week about 1500 Hungarians were shot down into the Danube in Novi Sad under the leadership of Todor Gavrilović. On 3 November 1944 in Bezdan Hungarian male inhabitants of the village in the age of between l6 and 5O years were driven to a sports ground. 118 men were shot down by machine pistol to the Danube. 2830 Serbian communist partisans who made the murder belonged to the udarna brigade No. 12 in the division No. 51. It is strange but the Soviet officers were also horrified at the massacre because they were who stopped further executions. On 3 December 1944 56 Hungarian citizens were executed on the bank of the Tisza river in Adorjan. In Žabalj 2,000 Hungarian citizens were killed.[5][6] In Subotica during the 1944-45 period about 8,000 citizens (mainly Hungarian) were killed by Yugoslav Partisans as retribution for supporting Hungary re-taking the city. At the end of war detachments of Serbian Partisans occupied Čurug and murdered 3000 local ethnic Hungarian residents. The surviving ethnic Hungarian residents of the village were deported to detention camps and were never allowed to return. Ethnic Hungarians Germans were declared to be collaborators or exploiters. Those suspected of not supporting the emerging Communist regime or who belonged to a "wrong" ethnic group were the targets of persecution.[7]

After World War II

Ever since the end of the Second World War, the Hungarian population has been steadily declining, mainly due to low birthrates and emigration. In 1974, the Yugoslav constitution was modified giving Vojvodina a very high level of autonomy and local Hungarians participated in Vojvodinian provincial administration. The Hungarians were also given the opportunity to keep their culture and language alive; they had their own schools and cultural institutions. During the reign of Josip Broz Tito, life in Vojvodina was peaceful for Hungarians as well as for others. The socialist regime heavily cracked down upon nationalist flareups.

As the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s were raging, more Hungarians left Vojvodina. One of the reasons for this emigration was the ruined economy of the country and inability for employment, which was the reason why many Serbs, as well as others, also emigrated from Vojvodina. Although the province was peaceful and calm compared to other areas of Yugoslavia, some Hungarians felt threatened, especially because Vojvodina was near the front lines during the War in Croatia. With an emigration of Hungarians from Vojvodina, one part of their former houses were used for the resettlement of refugees from other parts of the former Yugoslavia. This created a change of the ethnic structure in some parts of the region. The Hungarian population has fallen from 340,946 (16.9%) in 1991, to 290,207 (14.28%) in 2002. In recent years (mostly in 2004 and 2005), some members of the ethnic Hungarian community have sometimes been the targets of anti-Hungarian sentiment.

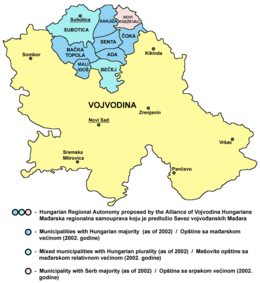

Today, many Hungarians in Vojvodina want their political rights to be extended. Some local Hungarian politicians proposing the creation of a new autonomous region in the northern part of Vojvodina inhabited mainly by Hungarians (see: Hungarian Regional Autonomy). They also want to attain Hungarian citizenship, without being Hungarian residents, as this would automatically make them EU citizens, giving many benefits. However, a referendum on this issue in Hungary failed. The political future of Vojvodinian Hungarians is uncertain, as their community is characterized by low birthrates and a dwindling population – according to some demographic predictions, Hungarians of Vojvodina will probably lose ethnic majority/plurality in some municipalities and sizable towns, but they will certainly remain in the majority in others. Thus, while Hungarians will remain a notable ethnic group in the northern part of Vojvodina, partial demographic changes in the area will probably reduce the demands of local Hungarian politicians for territorial autonomy or at least for wide territorial extension of the proposed Hungarian autonomous region.

Demographics

Almost all Hungarians in Serbia are to be found in Vojvodina, and especially in its northern part (North Bačka and North Banat districts, respectively) where majority (57.17%) of them live.[1] Hungarians in the five municipalities form the absolute majority: Kanjiža (85.13%), Senta (79.09%), Ada (75.04%), Bačka Topola (57.94%), and Mali Iđoš (53.91%). The ethnically mixed municipalities with relative Hungarian majority are Čoka (49.66%), Bečej (46.34%) and Subotica (35.65%). The multiethnic city of Subotica is a cultural and political centre for the Hungarians in Serbia. Protestant Hungarians form the plurality or majority of population in the settlements of Stara Moravica, Pačir, Feketić, Novi Itebej and Debeljača.

| Year | Hungarians | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1921 | 365,982 | 6.46% |

| 1931 | 413,000 | 7.27% |

| 1948 | 433,701 | 6.64% |

| 1953 | 441,907 | 6.33% |

| 1961 | 449,587 | 5.88% |

| 1971 | 430,314 | 5.09% |

| 1981 | 390,468 | 4.19% |

| 1991 | 343,942 | 4.24% |

| 2002 | 293,299 | 3.91% |

| 2011 | 253,899 | 3.53% |

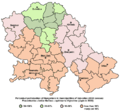

Percentual participation of Hungarians in Vojvodina according to the 2002 census (municipality data)

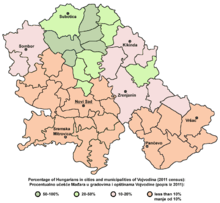

Percentual participation of Hungarians in Vojvodina according to the 2002 census (municipality data) Percentual participation of Hungarians in Vojvodina according to the 2011 census (municipality data)

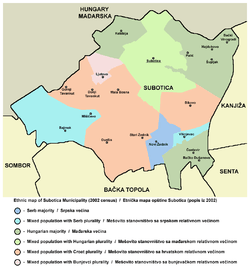

Percentual participation of Hungarians in Vojvodina according to the 2011 census (municipality data) Ethnic map of the Subotica municipality showing the location of settlements with Hungarian majority

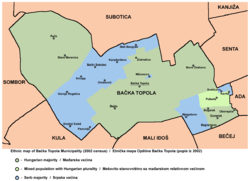

Ethnic map of the Subotica municipality showing the location of settlements with Hungarian majority Ethnic map of the Bačka Topola municipality showing the location of settlements with Hungarian majority

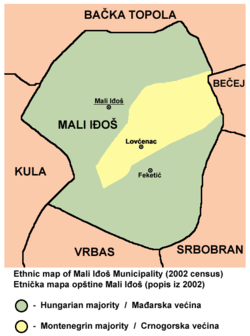

Ethnic map of the Bačka Topola municipality showing the location of settlements with Hungarian majority Ethnic map of the Mali Iđoš municipality showing the location of settlements with Hungarian majority

Ethnic map of the Mali Iđoš municipality showing the location of settlements with Hungarian majority

Religion

According to the 2011 Census, most Hungarians are part of the Catholic Church in Serbia (224,291 people, or 88.3% of all Hungarian people). [8] Around 6.2% belong to various forms of Protestantism and a much smaller number is part of the Eastern Orthodox Church (1.2%).

Politics

There are five main ethnic Hungarian political parties in Vojvodina:

- Alliance of Vojvodina Hungarians, led by István Pásztor

- Democratic Community of Vojvodina Hungarians, led by Áron Csonka

- Democratic Party of Vojvodina Hungarians, led by András Ágoston

- Civic Alliance of Hungarians, led by László Rác Szabó

- Movement of Hungarian Hope, led by Bálint László

These parties are advocating the establishment of the territorial autonomy for Hungarians in the northern part of Vojvodina, which would include the municipalities with Hungarian majority.

Culture

Media

- Magyar Szó, a Hungarian language daily newspaper published in Subotica

- Radio Television of Vojvodina broadcasts program in 10 local languages, including daily radio and TV shows in Hungarian language.

- Délmagyarország ("Southern Hungary") was a Hungarian language daily newspaper. The first issue was published on March 14, 1909, with the purpose of serving as the information source for the Hungarian language-speaking population in Bács-Bodrog County within the Kingdom of Hungary in Austria-Hungary. It was published in Subotica. Last issue of Délmagyarország was on June 27, 1909. Its editor-in-chief was Henrik Braun.

Notable people

Born before 1920 in the Kingdom of Hungary

- Paul Abraham, Jewish-Hungarian composer of operettas

- Géza Allaga, Hungarian composer, cellist and cimbalis

- József Bittenbinder, Hungarian gymnast who competed in the 1912 Summer Olympics

- Ugrin Csák, Hungarian nobleman and oligarch in the early 14th century

- Géza Csáth, physician, writer

- István Donogán, Hungarian track and field athlete

- József Hátszeghy, Hungarian fencer

- Ferenc Herczeg, playwright and author who promoted conservative nationalist opinion in his country

- Tibor Harsányi, composer and pianist

- Alexander Kasza, World War I flying ace credited with six aerial victories

- Dezső Kosztolányi, one of the most renowned Hungarian-language writer

- Vilmos Lázár, Hungarian general, one of the 13 Martyrs of Arad

- András Littay, Hungarian General during World War II

- Endre Madarász, Hungarian track and field athlete

- László Moholy-Nagy, Hungarian painter and photographer, notable professor of the Bauhaus school

- Károly Molter, Hungarian novelist

- Gyula Ortutay, Hungarian politician in FKGP

- Gyula Pártos, Hungarian architect

- Ferenc Rákosi, Hungarian field handball player who competed in the 1936 Summer Olympics

- Mátyás Rákosi, Communist leader of Hungary

- Jenő Rátz, Hungarian military officer

- Michael Szilágyi, general and Regent of Hungary in 1458

- Carl von Than, Hungarian chemist

- Mór Than, Hungarian painter

- József Vértesy, Hungarian water polo player

- Jenő Vincze, Hungarian footballer and a legend of Újpest, playing for the national team in the 1938 World Cup Final

- Henrik Werth, Hungarian military officer

Born after 1920 in Yugoslavia and Serbia

- Dalma Ružičić-Benedek, Hungarian-born sprint canoer

- Aranka Binder, sport shooter, bronze medal winner in Women's Air Rifle in the 1992 Summer Olympics

- Tamara Boros, Croatian table tennis player

- Zoltán Dani, former colonel of the Yugoslav Army who shot down an F-117 Nighthawk during the Kosovo War

- Lajos Engler, basketball player

- Szilvia Erdélyi, table tennis player

- Krisztian Frisz, wrestler

- László Györe, tennis player

- Vilim Harangozo, table tennis player

- Ervin Holpert, sprint canoer

- Jožef Holpert, handball goalkeeper

- Zoltán Illés, Hungarian politician in Fidesz

- Karolj Kasap, wrestler

- Gabor Kasa, cyclist

- József Kasza, politician, former leader of the Alliance of Vojvodina Hungarians

- Ervin Katona, strongman competitor

- Zsombor Kerekes, Hungary national football team player

- Mihály Kéri, footballer playing for Yugoslavia and United States

- Mihalj Kertes, politician, close associate of Slobodan Milošević

- Tereza Kočiš, gymnast

- Renata Kubik, sprint canoer

- Félix Lajkó, violinist and composer

- Péter Lékó, Hungarian Chess Grand Master

- Sylvester Levay, Hungarian composer

- Vilmos Lóczi, basketball player and coach

- Béla Mavrák, Hungarian tenor singer

- Đula Mešter, FR Yugoslav volleyball player, Olympic champion

- Brižitka Molnar, volleyball player

- Antonija Nađ, sprint canoeist

- Albert Nađ, footballer

- Viktor Nemeš, wrestler

- László Nemet, Roman Catholic bishop of Zrenjanin (Nagybecskerek)

- Nemanja Nikolić, footballer

- Erzsebet Palatinus, table tennis player

- Béla Pálfi, footballer

- Antónia Panda, sprint canoeist

- János Pénzes, Roman Catholic bishop of Subotica (Szabadka)

- Eva Ras, actress, writer, painter

- László Rátgéber, Hungarian basketball coach

- Magdolna Rúzsa, singer, winner of the third season of Megasztár (Hungarian Idol)

- Nandor Sabo, wrestler

- Szebasztián Szabó, swimmer

- Monica Seles, former World No.1 female tennis player

- Árpád Sterbik, world champion handball goalkeeper

- Csaba Szilágyi, Serbian Olympic swimmer

- Mario Szenessy, German author, translator, and literary critic

- Lajos Szűcs, Hungarian national football team player, gold medal winner at the 1968 Summer Olympics

- Marta Tibor, sprint canoer

- József Törtei, wrestler, bronze medal winner at the 1984 Summer Olympics

- Mihály Tóth, Hungarian footballer and a legend of Újpest, playing for the national team in the 1954 World Cup Final

See also

- Ethnic groups of Vojvodina

- Hungarian exonyms (Vojvodina)

- Hungarians in Slovakia

- Hungarians in Romania

- Székelys

- Hungarian-Serbian relations

Notes

| a. | ^ Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Kosovo and the Republic of Serbia. The Republic of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence on 17 February 2008, but Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. The two governments began to normalise relations in 2013, as part of the 2013 Brussels Agreement. Kosovo is currently recognized as an independent state by 97 out of the 193 United Nations member states. In total, 112 UN member states recognized Kosovo at some point, of which 15 later withdrew their recognition. |

Further reading

- Arday, Lajos (September 1996). "Hungarians in Serb-Yugoslav Vojvodina since 1944". Nationalities Papers. 24 (3): 467–482. doi:10.1080/00905999608408460.

References

- "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia" (PDF). Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- "Government of Vojvodina". vojvodina.gov.rs.

- "Results of 1900 and 1910 censuses in Hungary".

- "Tibor Cseres: Serbian Vendetta in Bacska". Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- "HUNSOR ~Vajdaság - "The freezing weeks" of 1944". Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- Administrator. "Változást - Hegedűs Antal: A bácskai vérengzések 1944 őszén". Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- 029, Project. "Budapesttelegraph.com - Budapest Telegraph News from Hungary". Retrieved 24 August 2016.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Population by national affiliation and religion, Census 2011

Notes

- Karolj Brindza, Učešće jugoslovenskih Mađara u narodnooslobodilačkoj borbi, Vojvodina u borbi, Matica Srpska, Novi Sad, 1951.

- Borislav Jankulov, Pregled kolonizacije Vojvodine u XVIII i XIX veku, Novi Sad - Pančevo, 2003.

- Peter Rokai - Zoltan Đere - Tibor Pal - Aleksandar Kasaš, Istorija Mađara, Beograd, 2002.

- Enike A. Šajti, Mađari u Vojvodini 1918-1947, Novi Sad, 2010.

- Aleksandar Kasaš, Mađari u Vojvodini 1941-1946, Novi Sad, 1996.

External links

- (in Hungarian) The encyclopedia of Vojvodina

- Hungarian population in the territory of present-day Vojvodina between 1880 and 1991

- Ethnic Hungarian Minorities in Central and Eastern Europe

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hungarians in Vojvodina. |