Portuguese people

The Portuguese people are a Romance nation[46][47][48] native to Portugal who share a common Portuguese culture, ancestry and language. Their predominant religion is Christianity, mainly Roman Catholicism, though other religions and irreligion are also present, especially among the younger generations.[49] The Portuguese people's heritage largely derives from the pre-Celts (Lusitanians, Conii)[50][51] and Celts (Gallaecians, Turduli and Celtici),[52][53][54] who were Romanized after the conquest of the region by the ancient Romans.[55][56] Y-DNA ratios in northern and central Portugal today indicate a small percentage of descent in male lineages from Germanic tribes who arrived after the Roman period as ruling elites, including the Suebi,[57][58][59][60][61] Vandals[62] and Visigoths,[63][64] who ruled for circa three hundred years. Finally, the Moorish occupation of Iberia also left a small Jewish and Arab-Berber genetic contribution in the Iberian Peninsula.[55][56]

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

c. 60 million[a][1][2][3][4][5]

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| c. 5,000,000 (eligible for Portuguese citizenship)[7] | |

| 1,720,000 (Portuguese born & ancestry)[8][9] | |

| 1,471,549 (Portuguese ancestry) | |

| 429,850 (Portuguese ancestry)[10] | |

| 336,975[11][12][13] | |

| 300,441(Only Portuguese ancestry: ~300,000)[14] (additional 55,441 Portuguese born)[15][16][17] | |

| 300,000 | |

| 300,000[18] | |

| 263,706[9] | |

| 174,363 | |

| 125,549[19] | |

| 116,505 | |

| 93,008[20] | |

| 73,731[21] | |

| 59,336[22] | |

| 50,157[23][24] | |

| 40,413[9] | |

| 25,893[25][26] | |

| 22,318[9] | |

| 16,505[27] | |

| 10,983[28][29] | |

| 10,764[30] | |

| 8,703[31] | |

| 6,609[32] | |

| 6.338[33] | |

| 5,568 [9] | |

| 4 945[34] | |

| 4,273[35] | |

| 4,000[36] | |

| 2,737[9] | |

| 2,661[37] | |

| 2,107[9] | |

| 2,045 | |

| 1,731[38] | |

| 1,614 [39] | |

| 1,574[40] | |

| 1,206[41] | |

| 992 | |

| 942[42] | |

| 635[43] | |

| Languages | |

| Portuguese, Mirandese | |

| Religion | |

| Catholic Christianity[44][45] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Galicians, Romance peoples, Celtic peoples, White Brazilians, White Angolans, Portuguese Africans | |

^a Total number of ethnic Portuguese varies wildly based on the definition. | |

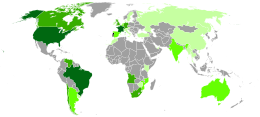

The Roman Republic conquered the Iberian Peninsula during the 2nd and 1st centuries B.C. from the extensive maritime empire of Carthage during the series of Punic Wars. As a result of Roman colonization, the Portuguese language stems primarily from Vulgar Latin. Due to the large historical extent from the 16th century of the Portuguese Empire and the subsequent colonization of territories in Asia, Africa and the Americas, as well as historical and recent emigration, Portuguese communities can be found in many diverse regions around the globe, and a large Portuguese diaspora exists.

Portuguese people began an Age of Exploration which started in 1415 with the conquest of Ceuta and culminated in an empire with territories that are now part of over 50 countries. The Portuguese Empire lasted nearly 600 years, seeing its end when Macau was returned to China in 1999. The discovery of several lands unknown to Europeans in the Americas, Africa, Asia and Oceania (southwest Pacific Ocean), forged the Portuguese Empire described as the first global maritime and commercial empire, becoming one of the world's major economic, political and military powers in the 15th and 16th centuries.[65][66][67] Portugal paved the way to the subsequent domination of Western civilisation by other neighbouring European nations.[68][69][70][67]

Ancestry

Historical origins and genetics

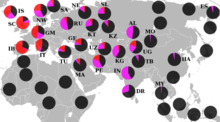

The Portuguese are a Southwestern European population, with origins predominantly from Southern and Western Europe. The earliest modern humans inhabiting Portugal are believed to have been Paleolithic peoples that may have arrived in the Iberian Peninsula as early as 35,000 to 40,000 years ago. Current interpretation of Y-chromosome and mtDNA data suggests that modern-day Portuguese trace a proportion of these lineages to the paleolithic peoples who began settling the European continent between the end of the last glaciation around 45,000 years ago.

Northern Iberia is believed to have been a major Ice-age refuge from which Paleolithic humans later colonized Europe. Migrations from what is now Northern Iberia during the Paleolithic and Mesolithic, links modern Iberians to the populations of much of Western Europe and particularly the British Isles and Atlantic Europe.[71] Recent books published by geneticists Bryan Sykes, Stephen Oppenheimer and Spencer Wells have emphasized a Paleolithic and Mesolithic Iberian influence in the modern day Irish, Welsh and Scottish gene-pool as well as parts of the English. Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b is the most common haplogroup in practically all of the Iberian peninsula and western Europe.[72]

Within the R1b haplogroup there are modal haplotypes. One of the best-characterized of these haplotypes is the Atlantic Modal Haplotype (AMH). This haplotype reaches the highest frequencies in the Iberian Peninsula and in the British Isles. In Portugal it reckons generally 65% in the South summing 87% northwards, and in some regions 96%.[73] The Neolithic colonization of Europe from Western Asia and the Middle East beginning around 10,000 years ago reached Iberia, as most of the rest of the continent although, according to the demic diffusion model, its impact was most in the southern and eastern regions of the European continent.[74]

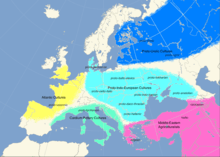

Starting in the 3rd millennium BC as well as in the Bronze Age, the first wave of migrations into Iberia of speakers of Indo-European languages occurred. These were later (7th and 5th centuries BC) followed by waves of Celts.[75][76]

These two processes defined Iberia's, and Portugal's, cultural landscape—Continental in the northwest and Mediterranean towards the southeast, as historian José Mattoso describes it.[77] The Northwest-Southeast cultural shift also shows in genetic differences: Based on Salas et al.[78] findings on the Haplogroup H, a cluster that is nested within haplogroup R category, is more prevalent along the Atlantic façade, including the Cantabrian coast and Portugal. It displays the highest frequency in Galicia (northwestern corner of Iberia). The frequency of haplogroup H shows a decreasing trend from the Atlantic façade towards the Mediterranean regions.

This finding adds strong evidence where Galicia and Northern Portugal was found to be a cul-de-sac population, a kind of European edge for a major ancient central European migration. Therefore, there is an interesting pattern of genetic continuity existing along the Cantabria coast and Portugal, a pattern that has been observed previously when minor sub-clades of the mtDNA phylogeny were examined[12].[80]

Given the origins from Paleolithic and Neolithic settlers as well as Indo-European migrations, one can say that the Portuguese ethnic origin is mainly a mixture of pre-Celts, (Celtiberians)[81] para-Celts such as the Lusitanians[81] of Lusitania, and Celtic[82] peoples such as Gallaeci of Gallaecia, the Celtici[83] and the Cynetes[84] of Alentejo and the Algarve. The Romans were also an important influence on Portuguese culture; the Portuguese language derives mostly from Latin.

After the Romans, Germanic peoples, namely the Suebi and the Visigoths, ruled the peninsula for several centuries and became part of the local populations. Some of the Vandals (Silingi and Hasdingi) as well as Alans[85] also remained. The Suebians of northern and central Portugal and of Galicia were the most numerous of the Germanic tribes. For that reason, Portugal and Galicia, (along with Catalonia which was part of the Frankish Kingdom), are the regions with the highest ratios of Germanic Y-DNA in the Iberian peninsula.[57]

The Moors occupied what is now Portugal from the 8th century until the Reconquista movement expelled them from the Algarve in 1249. Some of their population, mainly Berbers and Jews converted to Christianity and became Cristãos novos, still identifiable by their new surnames.[86] Adams et Al. and other previous publications, proposed that the Moorish occupation left a minor Jewish, Saqaliba[87] and some Arab-Berber genetic influence mainly in western and southern regions of Iberia.[88][89][55][56] The most comprehensive study of the Iberian genomic history for the past 8,000 years ever published to Mar 2019, concludes that the North African genetic can be identified throughout the whole Iberian Peninsula.[90] Religious and ethnic minorities such as the "new Christians" or "Ciganos" (Roma gypsies)[91] would later suffer persecution from the state and the Holy Inquisition and many were expelled and condemned under the Auto-da-fé[92] sentencing or fled the country, creating a Jewish diaspora in The Netherlands,[93] England, America,[94] Brazil,[95] The Balkans[96] and other parts of the world.

Other minor influences include Viking admixture with the native population between the 9th and 11th centuries. This was due to raids and small settlements made by Norsemen in coastal areas in the northern regions of Douro and Minho.[97][98][99][100]

For the Y-chromosome and MtDNA lineages of the Portuguese and other peoples see this map and this one.

The Portuguese have also maintained a certain degree of ethnic and cultural specific characteristics-ratio with the Basques,[101] since ancient times. The results of the present HLA study in Portuguese populations show that they have features in common with Basques and some Spaniards from Madrid: a high frequency of the HLA-haplotypes A29-B44-DR7 (ancient western Europeans) and A1-B8-DR3 are found as common characteristics. Many Portuguese and Basques do not show the Mediterranean A33-B14-DR1 haplotype, confirming a lower admixture with Mediterraneans.[80]

The Portuguese have a characteristic unique among world populations: a high frequency of HLA-A25-B18-DR15 and A26-B38-DR13, which may reflect a still detectable founder effect coming from ancient Portuguese, i.e., Oestriminis and Cynetes.[102] According to an early genetic study, the Portuguese are a relatively distinct population according to HLA data, as they have a high frequency of the HLA-A25-B18-DR15 and A26-B38-DR13 genes, the latter is a unique Portuguese marker. In Europe, the A25-B18-DR15 gene is only found in Portugal, and is also observed in white North Americans and in Brazilians (very likely of Portuguese ancestry).[103]

The pan-European (most probably Celtic) haplotype A1-B8-DR3 and the western-European haplotype A29-B44-DR7 are shared by Portuguese, Basques and Spaniards. The later is also common in Irish, southern English, and western French populations.[103]

The A2-B7-DR15 gene is common to those, the Cornish, Austrians and Germans, showing a much more ancient link between North Africans and western and central Europeans.[103]

R1b-5 gene cluster is a male re-expansion 15,000–13,000 years ago from Northwestern Iberia heading towards Ireland, Wales and Northern Scotland. The Rory gene cluster (R1b-14) is one of the largest re-expansions also head towards Ireland and Scotland, however featuring particularly in Irish men with Gaelic names.[104]

Lusitanians

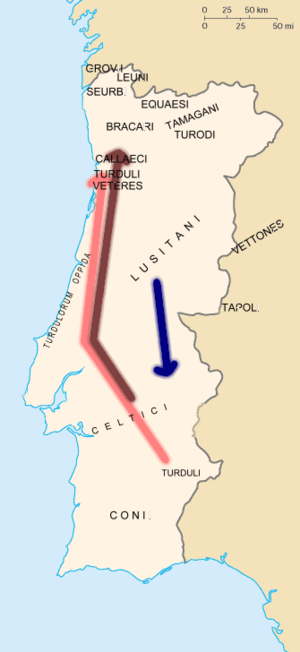

The Lusitanians (or Lusitānus/Lusitani in Latin) were an Indo-European speaking people living in the Western Iberian Peninsula long before it became the Roman province of Lusitania (modern Portugal, Extremadura and a small part of Salamanca). They spoke the Lusitanian language, of which only a few short written fragments survive. Most Portuguese consider the Lusitanians as their ancestors. Although the northern regions (Minho, Douro, Trás-os-Montes) identify more with the Gallaecians. Prominent modern linguists such as Ellis Evans believe that Gallaecian-Lusitanian was one same language (not separate languages) of the "p" Celtic variant.[105][106]

It has been hypothesized that the Lusitanians may have originated in the Alps and settled in the region in the 6th century BC. Some modern scholars like Daithi O Hogain consider them to be indigenous[107] and initially dominated by the Celts, before gaining full independence from them. The archaeologist Scarlat Lambrino proposed that they were originally a tribal Celtic[108] group, related to the Lusones.

The first area settled by the Lusitanians was probably the Douro valley and the region of Beira Alta; then they moved south, and expanded on both sides of the Tagus river, before being conquered by the Romans. The original Roman province of Lusitania was extended north of the areas occupied by the Lusitanians to include the territories of Asturias and Gallaecia but these were soon ceded to the jurisdiction of the Provincia Tarraconensis in the north, while the south remained the Provincia Lusitania et Vettones. After this, Lusitania's northern border was along the Douro river, while its eastern border passed through Salmantica and Caesarobriga to the Anas (Guadiana) river.

The Lusitanian ethnicity and particularly, their language is not totally certain. They originated from either Proto-Celtic or Proto-Italic populations who spread from Central Europe into western Europe after new Yamnaya migrations into the Danube Valley,[109][110] while Proto-Germanic and Proto-Balto-Slavic may have developed east of the Carpathian mountains, in present-day Ukraine,[111] moving north and spreading with the Corded Ware culture in Middle Europe (third millennium BCE).[112][113] Alternatively, a European branch of Indo-European dialects, termed "North-west Indo-European" and associated with the Bell Beaker culture, may have been ancestral to not only Celtic and Italic, but also to Germanic and Balto-Slavic.[114]

Pre-Roman groups

The Lusitanians were a large tribe that lived between the rivers Douro and Tagus. As the Lusitanians fought fiercely against the Romans for independence, the name Lusitania was adopted by the Gallaeci, tribes living north of the Douro, and other closely surrounding tribes, eventually spreading as a label to all the nearby peoples fighting Roman rule in the west of Iberia. It was for this reason that the Romans came to name their original province in the area, that initially covered the entire western side of the Iberian peninsula, Lusitania.

Tribes, often known by their Latin names, living in the area of modern Portugal, prior to Roman rule:

- Bardili (Turduli) – living in the Setúbal peninsula;

- Bracari – living between the rivers Tâmega and Cávado, in the area of the modern city of Braga;

- Callaici – living along and north of the Douro;

- Celtici – Celts living in Alentejo;

- Coelerni – living in the mountains between the rivers Tua and Sabor;

- Cynetes or Conii – living in the Algarve and the south of Alentejo;

- Equaesi – living in the most mountainous region of modern Portugal;

- Grovii – a mysterious tribe living in the Minho valley;

- Interamici – living in Trás-os-Montes and in the border areas with Galicia and León (in modern Spain);

- Leuni – living between the rivers Lima and Minho;

- Luanqui – living between the rivers Tâmega and Tua;

- Lusitani – being the most numerous and dominant of the whole region comprising most of Portugal;

- Limici – living in the swamps of the river Lima, on the border between Portugal and Galicia);

- Narbasi – living in the north of modern Portugal (interior) and nearby area of southern Galicia;

- Nemetati – living north of the Douro Valley in the area of Mondim;

- Oestriminis also referred to as Sefes and supposedly linked to the Cempsii[115] – there isn’t a consensus regarding their exact origins and location. They are believed to have been the first known humans to inhabit the whole Atlantic axe covering Portugal and Galicia, the people from ‘Finis terrae’ at the end of the Western world.[116][117]

- Paesuri – a dependent tribe of the Lusitanians, living between the rivers Douro and Vouga;

- Quaquerni – living in the mountains at the mouths of rivers Cávado and Tâmega;

- Seurbi – living between the rivers Cávado and Lima (or even reaching the river Minho);

- Tamagani – from the area of Chaves, near the river Tâmega;

- Tapoli – another dependent tribe of the Lusitanians, living north of the river Tagus, on the border between modern Portugal and Spain;

- Turduli – in the east of Alentejo (Guadiana Valley);

- Turduli Veteres – the "ancient Turduli" living south of the estuary of the river Douro;

- Turdulorum Oppida – Turduli living in the Portuguese region of Estremadura and Beira Litoral;

- Turodi – living in Trás-os-Montes and bordering areas of Galicia;

- Vettones – living in the eastern border areas of Portugal, and in Spanish provinces of Ávila and Salamanca, as well as parts of Zamora, Toledo and Cáceres;

- Zoelae – living in the mountains of Serra da Nogueira, Sanabria and Culebra, up to the mountains of Mogadouro in northern Portugal and adjacent areas of Galicia.

Romanization

Since 193 B.C., the Lusitanians had been fighting Rome and its expansion into the peninsula following the defeat and occupation of Carthage in North Africa. They defended themselves bravely for years, causing the Roman invaders serious defeats. In 150 B.C., they were defeated by Praetor Servius Galba: springing a clever trap, he killed 9,000 Lusitanians and later sold 20,000 more as slaves further northeast in the newly conquered Roman provinces in Gaul (modern France) by Julius Caesar. Three years later (147 B.C.), Viriathus became the leader of the Lusitanians and severely damaged the Roman rule in Lusitania and beyond. He commanded a confederation of Celtic tribes[118] and prevented the Roman expansion through guerrilla warfare. In 139 B.C. Viriathus was betrayed and killed in his sleep by his companions (who had been sent as emissaries to the Romans), Audax, Ditalcus and Minurus, bribed by Marcus Popillius Laenas. However, when Audax, Ditalcus and Minurus returned to receive their reward by the Romans, the Consul Servilius Caepio ordered their execution, declaring, "Rome does not pay traitors".

Viriathus[119] is the first ‘national hero’ for the Portuguese as Vercingetorix[120] is for the French or Boudicca[121] for the English. After Viriathus' rule, the celticized Lusitanians became largely romanized, adopting Roman culture and the language of Latin. The Lusitanian cities, in a manner similar to those of the rest of the Roman-Iberian peninsula, eventually gained the status of "Citizens of Rome". The Portuguese language itself is mostly a local later evolution of the Roman language, Latin after the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th and 6th centuries.

Demography

Demographics of Portugal

There are around 10 million native Portuguese in Portugal, out of a total population of 10.34 million (estimate).

Native minority languages in Portugal

A small minority of about 15,000 speak the Mirandese language, (part of the Asturian-Leonese linguistic group which includes the Asturian and Leonese minority languages of Northwestern Spain[122][123][124][125]) in the municipalities of Miranda do Douro, Vimioso and Mogadouro. All of the speakers are bilingual with Portuguese.

An even smaller minority of no more than 2,000 people speak Barranquenho, a dialect of Portuguese heavily influenced by southern Spanish, spoken in the Portuguese town of Barrancos (in the border between Extremadura and Andalusia, in Spain, and Portugal).

Ethnic minorities in Portugal

People from the former colonies, particularly Brazil, Portuguese Africa, Macau (China), Portuguese India and East Timor, have been migrating to Portugal since the 1900s. A great number of Slavs, especially Ukrainians (now the third biggest ethnic minority[126]) and Russians, as well as Moldovans and Romanians, keep migrating to Portugal. There is a Chinese minority of Macau Cantonese origin and mainland China. Indians and Nepalese are also relevant in numbers. In addition, there is a small minority of Gypsies (Ciganos) about 40,000 in number,[127] Muslims about 34,000 in number[128] and an even smaller minority of Jews of about 5,000 people (the majority are Sephardi such as the Belmonte Jews, while some are Ashkenazi). Portugal is also home to other EU and EEA/EFTA nationals (French, German, Dutch, Swedish, Italian, Spanish). The UK and France represented the largest senior residents communities in the country as of 2019.[129] Official migrants accounted to 4.7% of the population in 2019,[130][131] with the tendency to increase further.[132]

Portuguese diaspora

Overview

In the whole world there are easily more than one hundred million people with recognizable Portuguese ancestors, due to the colonial expansion and worldwide immigration of Portuguese from the 16th century onwards to India, the Americas, Macau (see Macanese people), East-Timor, Malaysia, Indonesia, Burma[133] and Africa. Between 1886 and 1966, Portugal after Ireland, was the second Western European country to lose more people to emigration.[134] From the middle of the 19th century to the late 1950s, nearly two million Portuguese left Europe to live mainly in Brazil and with significant numbers to the United States.[135] About 1.2 million Brazilian citizens are native Portuguese.[136] Significant verified Portuguese minorities exist in several countries (see table).[137] In 1989 some 4,000,000 Portuguese were living abroad, mainly in France, Germany, Brazil, South Africa, Canada, Venezuela, and the United States.[138] Within Europe, substantial concentrations of Portuguese may be found in Francophone countries like France, Luxembourg and Switzerland, spurred in part by their linguistic proximity with the French language.

Portuguese Sephardi Jews

Descendants of Portuguese Sephardi Jews are found in Israel, the Netherlands, the United States, France, Venezuela, Brazil[139] and Turkey. In Brazil many of the colonists were also originally Sephardi Jews, who, converted, were known as New Christians.

The Americas outside of Brazil and the Pacific

In the United States, there are Portuguese communities in New Jersey, the New England states, and California. Springfield, Illinois once possessed the largest Portuguese Community in the Midwest.[140] In the Pacific, Hawaii has a sizable Portuguese element that goes back 150 years (see Portuguese Americans), Australia and New Zealand also have Portuguese communities (see Portuguese Australians, Portuguese New Zealanders). Canada, particularly Ontario, Quebec and British Columbia, has developed a significant Portuguese community since 1940 (see Portuguese Canadians). Argentina (See Portuguese Argentine and Cape Verdean Argentine) and Uruguay (see Portuguese Uruguayan) had Portuguese immigration in the early 20th century. Portuguese fishermen, farmers and laborers dispersed across the Caribbean, especially Bermuda (3.75%[141] to 10%[142] of the population), Guyana (4.3% of the population in 1891),[143] Trinidad,[144] St. Vincent and the Grenadines, and the island of Barbados where there is high influence from the Portuguese community.[145]

Africa

In the early twentieth century the Portuguese government encouraged white emigration to Angola and Mozambique, and by the 1970s, there were up to 1 million Portuguese settlers living in their overseas African provinces.[146] An estimated 800,000 Portuguese returned to Portugal as the country's African possessions gained independence in 1975, after the Carnation Revolution, while others moved to South Africa, Botswana and Algeria.[147][148][149][150][151]

In Europe outside of Portugal

Portuguese constitute 13% of the population of Luxembourg. In 2006 there were estimates to be around half a million people of Portuguese origin in the United Kingdom (see Portuguese in the United Kingdom)—this is considerably larger than around the 88,000 Portuguese-born people alone residing in the country in 2009 (estimation; however this figure does not include British-born people of Portuguese descent). In areas such as Thetford and the crown dependencies of Jersey and Guernsey, the Portuguese form the largest ethnic minority groups at 30% of the population, 7% and 3% respectively. The British capital London is home to the largest number of Portuguese people in the UK, with the majority being found in the boroughs of Kensington and Chelsea, Lambeth and Westminster.[152] The Portuguese diaspora communities still are very attached to their language, their culture and their national dishes and particularly the bacalhau.[153]

Portuguese Diaspora in the rest of the world

There are Portuguese influenced people with their own culture and Portuguese based dialects in parts of the world other than former Portuguese colonies, notably in Barbados, Jamaica, Aruba, Curaçao, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana (see Portuguese immigrants in Guyana), Equatorial Guinea and throughout Asia (Main Article Luso-Asians).

Luso-Asian communities exist in Malaysia, Singapore (see Kristang people), Indonesia, Sri Lanka (see Burgher people and Portuguese Burghers), Myanmar (see Bayingyi people)[154][155] Thailand, India (see Luso-Indian) and Japan.[156][157][158][159][160]

List of countries by population of Portuguese heritage

| Country | Population | % of country | Criterion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Portuguese in North America | |||

| 1,477,335 | 0.5% | ||

| 429,850 | 1.3% | Canada 2011 Census[162] | |

| Portuguese in South America | |||

| 40,100 | 0.9% | [28] | |

| 5,000,000 (children and grandchildren, eligible for Portuguese citizenship) | 2,5% (children and grandchildren, eligible for Portuguese citizenship) | ||

| 55,441 | 3.8% | ||

| Portuguese in Europe | |||

| 1,720,000 | 2.5% | [165] | |

| 268,012 | 1.2% | ||

| 88,161 | 0.08% | ||

| 20,981 | 0.11% | ||

| 82,300 | 16.1% |

They constitute 16.1% of the population of Luxembourg, which makes them | |

| Portuguese in Asia (See Luso-Asian) | |||

| 200,000 | 0.02% | ||

| 25,000 – 46,000 | 2% | ||

| 5,000 | 0.02% | ||

| ~ 3,000+ | 0.02% | [154][157][155] | |

| 1,400 – 2,000 | 0.02% | [157] | |

| 37,000 | |||

| Portuguese in Oceania | |||

| 56,000 | 0.4% | ||

| 650 | 0.02% | ||

| Portuguese in Africa | |||

| 500,000 | 1% | ||

| 200,000 | 0.36% | ||

| 126,476 | 0.15% | ||

| Total in Diaspora | ~70,000,000 | ||

| 10,276,617 | Statistics Portugal (*Jun 2019)

[174] Figure is only a population estimate of all residents of Portugal, and includes people of non-Portuguese ethnic origin | ||

| Total Worldwide | unknown |

Portuguese ancestry in the Brazilian population

| Source: Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics (IBGE) | |||||||||||||||

| Decade | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | 1500–1700 | 1701–1760 | 1808–1817 | 1827–1829 | 1837–1841 | 1856–1857 | 1881–1900 | 1901–1930 | 1931–1950 | 1951–1960 | 1961–1967 | 1981–1991 | |||

| Portuguese | 100,000 | 600,000 | 24,000 | 2,004 | 629 | 16,108 | 316,204 | 754,147 | 148,699 | 235,635 | 54,767 | 4,605 | |||

In colonial times, over 700,000 Portuguese settled in Brazil, and most of them went there during the gold rush of the 18th century.[175] Brazil received more European settlers during its colonial era than any other country in the Americas. Between 1500 and 1760, about 700,000 Europeans immigrated to Brazil, compared to 530,000 European immigrants in the United States.[176][177] They managed to be the only significant European population to populate the country during colonization, even though there were French and Dutch invasions. The Portuguese migration was strongly marked by the predominance of men (colonial reports from the 16th and 17th centuries almost always report the absence or rarity of Portuguese women). This lack of women worried the Jesuits, who asked the Portuguese King to send any kind of Portuguese women to Brazil, even the socially undesirable (e.g. prostitutes or women with mental maladies such as Down Syndrome) if necessary.[178][179] The Crown responded by sending groups of Iberian orphan maidens to marry both cohorts of marriageable men, the nobles and the peasants. Some of which were even primarily studying to be nuns.[178][180]

The Crown also shipped over many Órfãs d'El-Rei of what was considered "good birth" to colonial Brazil to marry Portuguese settlers of high rank. Órfãs d'El-Rei (modern Portuguese órfãs do rei) literally translates to "Orphans of the King", and they were Portuguese female orphans in nubile age.[181] There were noble and non-noble maidens and they were daughters of military compatriots who died in battle for the king or noblemen who died overseas and whose upbringing was paid by the Crown.[181] Bahia's port in the East received one of the first groups of orphans in 1551.[182] The multiplication of descendants of Portuguese settlers also happened to a large degree through miscegenation with black and amerindian women. In fact, in colonial Brazil the Portuguese men competed for the women, because among the African slaves the female component was also a small minority.[183] This explains why the Portuguese men left more descendants in Brazil than the Amerindian or African men did. The Indian and African women were "dominated" by the Portuguese men, preventing men of color to find partners with whom they could have children. Added to this, White people had a much better quality of life and therefore a lower mortality rate than the black and indigenous population. Then, even though the Portuguese migration during colonial Brazil was smaller (3.2 million Indians estimated at the beginning of colonization and 3.6 million Africans brought since then, compared to the descendants of the over 700,000 Portuguese immigrants) the "white" population (whose ancestry was predominantly Portuguese) was as large as the "non-white" population in the early 19th century, just before independence from Portugal.[183] After independence from Portugal in 1822, around 1.7 million Portuguese immigrants settled in Brazil.[183]

Portuguese immigration into Brazil in the 19th and 20th centuries was marked by its concentration in the states of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. The immigrants opted mostly for urban centers. Portuguese women appeared with some regularity among immigrants, with percentage variation in different decades and regions of the country. However, even among the more recent influx of Portuguese immigrants at the turn of the 20th century, there were 319 men to each 100 women among them.[184] The Portuguese were different from other immigrants in Brazil, like the Germans,[185] or Italians[186] who brought many women along with them (even though the proportion of men was higher in any immigrant community). Despite the small female proportion, Portuguese men married mainly Portuguese women. Female immigrants rarely married Brazilian men. In this context, the Portuguese had a rate of endogamy which was higher than any other European immigrant community, and behind only the Japanese among all immigrants.[187]

.jpg)

Even with Portuguese heritage, many Portuguese-Brazilians identify themselves as being simply Brazilians, since Portuguese culture was a dominant cultural influence in the formation of Brazil (like many British Americans in the United States, who will never describe themselves as of British extraction, but only as "Americans", since British culture was a dominant cultural influence in the formation of The United States).

In 1872, there were 3.7 million Whites in Brazil (the vast majority of them of Portuguese ancestry), 4.1 million mixed-race people (mostly of Portuguese-African-Amerindian ancestry) and 1.9 million Blacks. These numbers give the percentage of 80% of people with total or partial Portuguese ancestry in Brazil in the 1870s.[188]

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a new large wave of immigrants from Portugal arrived. From 1881 to 1991, over 1.5 million Portuguese immigrated to Brazil. In 1906, for example, there were 133,393 Portuguese-born people living in Rio de Janeiro, comprising 16% of the city's population. Rio is, still today, considered the largest "Portuguese city" outside of Portugal itself, with 1% Portuguese-born people.[176][189]

Genetic studies also confirm the strong Portuguese genetic influence in Brazilians. According to a study, at least half of the Brazilian population's Y Chromosome (male inheritance) comes from Portugal. Black Brazilians have an average of 48% non-African genes, most of them may come from Portuguese ancestors. On the other hand, 33% Amerindian and 28% African contribution to the total mtDNA (female inheritance) of white Brazilians was found[3][4]

An autosomal study from 2013, with nearly 1300 samples from all of the Brazilian regions, found a predominant degree of European ancestry (mostly Portuguese, due to the dominant Portuguese influx among European colonization and immigration to Brazil) combined with African and Native American contributions, in varying degrees. 'Following an increasing North to South gradient, European ancestry was the most prevalent in all urban populations (with values from 51% to 74%). The populations in the North consisted of a significant proportion of Native American ancestry that was about two times higher than the African contribution. Conversely, in the Northeast, Center-West and Southeast, African ancestry was the second most prevalent. At an intrapopulation level, all urban populations were highly admixed, and most of the variation in ancestry proportions was observed between individuals within each population rather than among population'.[190]

A large community-based multicenter autosomal study from 2015, considering representative samples from three different urban communities located in the Northeast (Salvador, capital of Bahia), Southeast (Bambuí, interior of Minas Gerais) and South Brazilian (Pelotas, interior of Rio Grande do Sul) regions, estimated European ancestry to be 42.4%, 83.8% and 85.3%, respectively.[191] In all three cities, European ancestors were mainly Iberian.

It was estimated that around 5 million Brazilians (2,5% of the population) can acquire Portuguese citizenship, due to the last Portuguese nationality law that grants citizenship to grandchildren of Portuguese nationals.[7]

See also

References

- "Estudo descobre 31,19 milhões de portugueses pelo mundo". Dn.pt. Archived from the original on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- Portuguese ethnicity is more clear-cut than Spanish ethnicity, but here also, the case is complicated by the Portuguese ancestry of populations in the former colonial empire. Portugal has 10 million nationals. The 40 million figure is due to a study estimating a total of an additional 31 million descendants from Portuguese including grandparents; these people would be eligible for Portuguese citizenship under Portuguese nationality law (which grants citizenship to grandchildren of Portuguese nationals). Emigração: A diáspora dos portugueses Archived 28 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine (2009)

- Parra FC, Amado RC, Lambertucci JR, Rocha J, Antunes CM, Pena SD (January 2003). "Color and genomic ancestry in Brazilians". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (1): 177–82. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100..177P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0126614100. PMC 140919. PMID 12509516.

- Pena SD, Di Pietro G, Fuchshuber-Moraes M, Genro JP, Hutz MH, Gomes Kehdy F, et al. (February 2011). "The genomic ancestry of individuals from different geographical regions of Brazil is more uniform than expected". PLOS ONE. 6 (2): e17063. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...617063P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017063. PMC 3040205. PMID 21359226.

- "Portugal wants its emigrants back – so it's paying them to return".

- "Foreign population with regular residence as a % of the resident population: total and by sex (2018)". Statistics Portugal, Foreigners and Borders Service and Ministry of Internal Administration. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- NOVAimagem.co.pt / Portugal em LInha (17 February 2006). "Cinco milhões de netos de emigrantes podem tornar-se portugueses". Noticiaslusofonas.com. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- "Présentation du Portugal" (in French). France Diplomatie. 18 October 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- "Observatório da Emigração" [Emigration Observatory] (in Portuguese). Observatório da Emigração. 27 May 2014. Archived from the original (XLS) on 26 July 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- "Ethnic Origin (264), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age Groups (10) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2011 National Household Survey". 8 May 2013.

- Rausa, Fabienne; Sara Reist (2008). Ausländerinnen und Ausländer in der Schweiz: Bericht 2008 [Foreigners in Switzerland: Report 2008] (PDF) (in German). Neuchâtel: Swiss Federal Statistical Office. p. 16. ISBN 978-3-303-01243-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 August 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- Afonso, Alexandre (2015). "Permanently Provisional. History, Facts & Figures of Portuguese Immigration in Switzerland". International Migration. 53 (4): 120–134. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.2010.00636.x.

- "Observatório da Emigração".

- "Ministro de Portugal discutiu crise na Venezuela "todos os dias" na Assembleia Geral". 26 September 2019.

- "Observatório da Emigração".

- "Crisis has Venezuela's Portuguese returning to roots". 6 February 2019.

- "Reforço consular em países à volta da Venezuela". Publico.pt. 8 December 2019.

- "José Eduardo dos Santos diz que trabalhadores portugueses são bem-vindos em Angola". Observatório da Emigração. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

...presença de cerca de 200 mil trabalhadores portugueses no país...

- "Observatório da Emigração".

- "Población y edad media por nacionalidad y sexo". Ine.es. 30 October 2019.

- "Observatório da Emigração".

- "Observatório da Emigração".

- "The Portugal-born Community". Dss.gov.au. Archived from the original on 31 May 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- "Observatório da Emigração". Archived from the original on 31 March 2016.

- CBS Statline

- "Observatório da Emigração".

- "Observatório da Emigração".

- "Expresso". Jornal Expresso. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- "Observatório da Emigração".

- "Departament d'Estadística".

- "Observatório da Emigração".

- "Observatório da Emigração".

- "Portoghesi in Italia - statistiche e distribuzione per regione".

- "Embaixada de Portugal na Rússia".

- "Befolkning efter födelseland, ålder, kön och år". Statistiska centralbyrån.

- "SIC Notícias | Salários altos e ausência de impostos atrai portugueses aos Emirados Árabes Unidos". SIC Notícias.

- "Observatório da Emigração".

- "Observatório da Emigração".

- "Observatório da Emigração".

- "Bermuda Population Statistics and Census Data". Bermuda 4u.

- "Observatório da Emigração".

- "2013 Census ethnic group profiles: Portuguese". Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- "Observatório da Emigração".

- Faris, Robert N. (2014). Liberating Mission in Mozambique: Faith and Revolution in the Life of Eduardo Mondlane. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 114. ISBN 9781630874841.

- Cavendish, Marshall (2002). Peoples of Europe. Marshall Cavendish. p. 382. ISBN 9780761473787.

- Pop, Ioan-Aurel (1996). Romanians and Hungarians from the 9th to the 14th century. Romanian Cultural Foundation. ISBN 0880334401.

We could say that contemporary Europe is made up of three large groups of peoples, divided on the criteria of their origin and linguistic affiliation. They are the following: the Romanic or neo-Latin peoples (Italians, Spaniards, Portuguese, French, Romanians, etc.), the Germanic peoples (Germans proper, English, Dutch, Danes, Norwegians, Swedes, Icelanders, etc.), and the Slavic peoples (Russians, Ukrainians, Belorussians, Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Bulgarians, Serbs, Croats, Slovenians, etc.

- Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 533. ISBN 0313309841.

The Portuguese are a Latin nation

- Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 776. ISBN 978-0313309847.

Romance (Latin) nations... Portuguese

- Gomes, João Francisco. "Ateus e agnósticos são mais instruídos do que os religiosos, conclui estudo". Observador (in Portuguese). Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Jr, Walter C. Opello (9 July 2019). Portugal: From Monarchy to Pluralist Democracy. ISBN 9781000307764.

- https://ppg.revistas.uema.br/index.php/brathair/article/download/1785/1305

- "Portugal - History". Britannica. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "Vista de "Lancea", palabra lusitana, y la etnogénesis de los "Lancienses"". Revistas.ucm.es. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. ISBN 9781438129181.

- Bycroft, Clare; et al. (2019). "Patterns of genetic differentiation and the footprints of historical migrations in the Iberian Peninsula". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 551. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10..551B. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-08272-w. PMC 6358624. PMID 30710075.

- Olalde, Iñigo; et al. (2019). "The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years". Science. 363 (6432): 1230–1234. Bibcode:2019Sci...363.1230O. doi:10.1126/science.aav4040. PMC 6436108. PMID 30872528.

- https://www.eupedia.com/genetics/spain_portugal_dna.shtml

- https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/KingListsEurope/BarbarianSuevi.htm

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "BNP - Os búrios". Bibliografia.bnportugal.gov.pt. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- https://repositorio-aberto.up.pt/bitstream/10216/121781/2/229486.pdf

- "(PDF) IN TEMPORE SUEBORUM. The time of the Suevi in Gallaecia (411-585 AD)". Academia.edu. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- "L'Europe héritière de l'Espagne wisigothique". Books.openedition.org. 23 January 2014.

- https://alpha.sib.uc.pt/?q=content/o-património-visigodo-da-l%C3%ADngua-portuguesa

- Melvin Eugene Page, Penny M. Sonnenburg, p. 481

- "(PDF) The First Globalization: The Portuguese and the Age of Discovery". Academia.edu. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "A brief history of globalization". Weforum.org. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Crowley, Roger (15 September 2015). Conquerors: How Portugal seized the Indian Ocean and forged the First Global Empire. ISBN 9780571290918.

- Page, Martin (2002). The First Global Village: How Portugal Changed the World. ISBN 9789724613130.

- "(PDF) The Cradle of Globalisation Venice's and Portugal's Contribution to a World Becoming Global". Academia.edu. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- https://www.cepese.pt/portal/pt/investigacao/livro-historia-da-populacao-portuguesa

- Pericić M, Lauc LB, Klarić IM, Rootsi S, Janićijevic B, Rudan I, et al. (October 2005). "High-resolution phylogenetic analysis of southeastern Europe traces major episodes of paternal gene flow among Slavic populations". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 22 (10): 1964–75. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi185. PMID 15944443.

- Čeština: Distribuce genu R1b napříč Evropou (15 June 2012). "File:R1b-DNA-Distribution – Wikimedia Commons". Commons.wikimedia.org. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- Dupanloup I, Bertorelle G, Chikhi L, Barbujani G (July 2004). "Estimating the impact of prehistoric admixture on the genome of Europeans". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 21 (7): 1361–72. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh135. PMID 15044595.

- Cunliffe, Barry (2008). Europe between the oceans : themes and variations, 9000 BC-AD 1000 (First printed in paperback 2011. ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 254–258. ISBN 978-0-300-17086-3.

- Bowman, Sheridan; Stuart Needham (2007). "The Dunaverney and Little Thetford Flesh-Hooks: History, Technology and Their Position within the Later Bronze Age Atlantic Zone Feasting Complex" (PDF). The Antiquaries Journal. 87: 53–108. doi:10.1017/s0003581500000846. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- Mattoso, José (dir.), História de Portugal. Primeiro Volume: Antes de Portugal, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores, 1992. (in Portuguese)

- Barral-Arca R, Pischedda S, Gómez-Carballa A, Pastoriza A, Mosquera-Miguel A, López-Soto M, et al. (21 July 2016). "Meta-Analysis of Mitochondrial DNA Variation in the Iberian Peninsula". PLOS ONE. 11 (7): e0159735. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1159735B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0159735. PMC 4956223. PMID 27441366.

- "Ethnographic Map of Pre-Roman Iberia (circa 200 b". Arkeotavira.com. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- Pimenta, J.; Lopes, A. M.; Carracedo, A.; Arenas, M.; Amorim, A.; Comas, D. (2019). "Spatially explicit analysis reveals complex human genetic gradients in the Iberian Peninsula". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 7825. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.7825P. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-44121-6. PMC 6534591. PMID 31127131.

- Smith, William (1854). "Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography".

- Carlos Quiles. "Aquitanian Archives". Indo-European.eu. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. ISBN 9781438129181.

- Guest, Edwin (1971). Origines Celticae (A Fragment) and Other Contributions to the History of Britain. ISBN 9780804612234.

- https://www.academia.edu/13589202/_Nós_somos_Alanos_Documentos_Mitos_e_Concepções_dos_Alanos_no_Ocidente_Ibérico

- Jarvis, Judith K.; Levin, Susan L.; Yates, Donald N. (10 May 2018). Book of Jewish and Crypto-Jewish Surnames. ISBN 9781985856561.

- Gordon, Matthew; Hain, Kathryn A. (2017). Concubines and Courtesans: Women and Slavery in Islamic History. ISBN 9780190622183.

- "Tracing Past Human Male Movements in Northern/Eastern Africa and Western Eurasia". Academic.oup.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- Adams SM, Bosch E, Balaresque PL, Ballereau SJ, Lee AC, Arroyo E, et al. (December 2008). "The genetic legacy of religious diversity and intolerance: paternal lineages of Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula". American Journal of Human Genetics. 83 (6): 725–36. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.11.007. PMC 2668061. PMID 19061982.

- https://reich.hms.harvard.edu/sites/reich.hms.harvard.edu/files/inline-files/2019_Olalde_Science_IberiaTransect_2.pdf

- Numa breve cronologia: 1526 - Alvará de João III, de 13 de Março de 1526, proibiu que os ciganos entrassem no reino, e ordenou que saíssem os que cá estavam; 1538 - Nova lei de 26 de Novembro desse ano, ordenando a sua expulsão; 1592 - Lei de 28 de Agosto agravou as penas contra os ciganos que dentro de 4 meses não saíssem de Portugal; Ordenações Filipinas, proíbindo a entrada no Reino; 1606 - Alvará de 7 de Janeiro exigindo a observância das Ordenações, com a mesma pena agravada com degredo para as galés e com severas cominações para os magistrados remissos; 1614 - Nova carta régia de 3 de Dezembro impedindo a sua entrada no Reino; 1618 - Carta régia de 28 de Março em que o monarca mandava averiguar se no Reino andavam ciganos com «traje e língua diferente dos naturais»; 1654 - D. João IV mandou prender os ciganos que havia no Reino e embarcá-los para Maranhão, Cabo Verde e São Tomé; 1718 - D. João V, em 10 de Dezembro de 1718, determinou a expulsão dos ciganos. Ver Joel Serrão, Dicionário de História de Portugal, ed. de 2006.

- "Auto Da Fé". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- https://brill.com/view/title/12707

- https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/the-sephardic-diaspora-after-1492/

- http://www.uel.br/seer/index.php/histensino/article/download/11251/10021

- http://www.centrodehistoria-flul.com/uploads/7/1/7/0/7170743/jews_of_portugal_and_the_spanish-portuguese_jewish_diaspora_-_program30.5.18.pdf

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "História da Póvoa de Varzim" (in Portuguese). Memória Portuguesa.

- "09" (PDF). Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "Vikings- Warriors from the sea". Portugal.um.dk. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Arnaiz-Villena, Antonio (6 December 2012). Prehistoric Iberia: Genetics, Anthropology, and Linguistics. ISBN 9781461542315.

- Arnaiz-Villena A, Martínez-Laso J, Gómez-Casado E, Díaz-Campos N, Santos P, Martinho A, Breda-Coimbra H (14 May 2014). "Relatedness among Basques, Portuguese, Spaniards, and Algerians studied by HLA allelic frequencies and haplotypes". Immunogenetics. 47 (1): 37–43. doi:10.1007/s002510050324. PMID 9382919.

- Galbraith W, Wagner MC, Chao J, Abaza M, Ernst LA, Nederlof MA, et al. (1997). "Imaging cytometry by multiparameter fluorescence". Cytometry. 12 (7): 579–96. doi:10.1002/cyto.990120702. PMID 1782829.

- Oppenheimer, Stephen (2006). The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain. Constable & Robinson ltd.

- https://ilg.usc.es/agon/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/Callaica_Nomina.pdf

- Celtic Culture: A-Celti. 2006. ISBN 9781851094400.

- Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí (2002). The Celts: A History. Cork: The Collins Press. p. 73. ISBN 9780851159232.

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Lusitani

- Mallory 1999, pp. 108 f..

- Anthony 2007, pp. 345, 361–367.

- Anthony 2007, pp. 368, 380.

- Mallory 1999, pp. 108, 244–250.

- Anthony 2007, p. 360.

- James P. Mallory (2013). "The Indo-Europeanization of Atlantic Europe". In J. T. Koch; B. Cunliffe (eds.). Celtic From the West 2: Rethinking the Bronze Age and the Arrival of Indo–European in Atlantic Europe. Oxford: Oxbow Books. pp. 17–40.

- Chao, Eduardo (1849). "Cuadros de la geografia historica de Espana desde los primeros tiempos historicos hasta el dia (Etc.)".

- Corbal, Margarita Vazquez. "The southwestern border between Galicia and Portugal during the 12th and 13th centuries: A space for experimentation and artistic transmission". The Reading Medievalist, 3, "Selected Proceedings from "On the Edge" GCMS Graduate Conference, 2015 – via Academia.

- Ferreira, Marta Leite. "Lisboa não é a capital de Portugal e outros 9 factos que não aprendeu nas aulas de História". Observador.

- "Portugal - History". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Silva, Luis (30 July 2013). Viriathus: and the Lusitanian Resistance to Rome 155-139 BC. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781473826892 – via Google Books.

- "Vercingetorix | Gallic chieftain". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- "Boudicca | History, Facts, & Death". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- "Unesco.org". Unesco.org. 9 August 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- "Asturiano/Leonés". Azkuefundazioa.eus. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- "Promotora Española de Lingüística". Proel.org. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- "Un enclave lingüístico astur-leonés sobrevive en la "raia" portuguesa". Lavozdegalicia.es. 20 March 2010. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- "Portal SEF". Sef.pt. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- "European Roma Rights Centre". Errc.org. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- "A Imigração em Portugal, Comunidades lusófonas, Países do Leste da Europa". Imigrantes.no.sapo.pt. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ), Catarina Reis Oliveira (Coord; Gomes, Natália (July 2019). Estatísticas do Bolso da Imigração. ISBN 9789896851019.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- https://www.pordata.pt/Europa/População+estrangeira+em+percentagem+da+população+residente-1624

- Henriques, Joana Gorjão. "Imigrantes são 4% da população. Portugal precisa de mais". PÚBLICO.

- "Imigração para Portugal já cresceu 18% em 2019 (e ainda vai aumentar)". Jornal Expresso.

- https://www.joaoroqueliteraryjournal.com/nonfiction-1/2018/2/6/the-baying-people-of-burma

- "Portugal – Emigration". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- Jorge Malheiros (1 December 2002). "Portugal Seeks Balance of Emigration, Immigration". Migrationinformation.org. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- "Estatísticas gerais: imigrantes e descendentes" [General statistics: immigrants and descendants] (in Spanish). State Government of São Paulo. Archived from the original on 25 April 2006. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- Direcção Geral dos Assuntos Consulares e Comunidades Portuguesas do Ministério dos Negócios Estrangeiros (1999), Dados Estatísticos sobre as Comunidades Portuguesas, IC/CP – DGACCP/DAX/DID – Maio 1999.

- "Migration – Portugal – average, annual". Nationsencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- "Cristãos-Novos no Brasil Colônia" [New-Christians in colonial Brazil] (in Portuguese). IBGE. Archived from the original on 6 March 2001. Retrieved 7 July 2007.

- Martin, Andrea. "Carpenter Street Underpass" (PDF). Springfield Railroads Improvement Project. US Department of Transportation Federal Railroad Administration and the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Joshua Project. "Bermuda :: Joshua Project". Joshuaproject.net. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- "Bermuda". Solarnavigator.net. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- "Portuguese emigration from Madeira to British Guiana". Guyana.org. 7 May 2000. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- Pidduck, Angela (14 June 1999). "Small TT / Portuguese Community Continues to Celebrate Heritage". nalis.gov.tt. Archived from the original on 25 February 2002. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- "The Portuguese of the West Indies". Freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com. 31 July 2001. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- Portugal – Emigration, Eric Solsten, ed. Portugal: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1993.

- "Argélia".

- "Portugueses em Botsuana – Expats portugueses em Botsuana".

- Dismantling the Portuguese Empire, Time Magazine (7 July 1975)

- "Portugueses são mais parecidos com os argelinos do que costumamos pensar". TSF Rádio Notícias. 10 March 2015.

- "Argélia quer formação profissional portuguesa". Dinheiro Vivo. 29 November 2018.

- "UK-Portuguese Newspaper Launched in Thetford Norfolk". NewswireToday. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- SILVA, A. J. M. (2015), The fable of the cod and the promised sea. About Portuguese traditions of bacalhau, in BARATA, F. T- and ROCHA, J. M. (eds.), Heritages and Memories from the Sea, Proceedings of the 1st International Conference of the UNESCO Chair in Intangible Heritage and Traditional Know-How: Linking Heritage, 14–16 January 2015. University of Evora, Évora, pp. 130–143. PDF version

- Thu, Mratt Kyaw. "The 400-year history of Portuguese Catholics in Sagaing". Frontier Myanmar. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- "The Bayingyi People of Burma". Joao-Roque Literary Journal est. 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- "Embaixada de Portugal em Tóquio | Portal dedicado à divulgação das atividades da Embaixada de Portugal em Tóquio. Disponível informação relativa a relações bilaterais entre Portugal e Japão, Agência para o Investimento e Comércio Externo de Portugal, Secção Consular e Secção Cultural, bem como todos os contactos úteis, localização e horários de funcionamento".

- Combustões (19 July 2009). "Portuguese descendants in Thailand". 500 Anos Portugal-Tailândia, por Miguel Castelo Branco. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- "Bangkok enclave celebrates its Portuguese past".

- Reis, Bárbara. "Portugal quer redescobrir a Índia. Outra vez". PÚBLICO.

- "Nova Deli por quem lá vive: Jorge Roza de Oliveira". 10 April 2014.

- "2008 Community Survey". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- Statistics Canada (8 May 2013). "2011 National Household Survey: Data tables". Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- NOVAimagem.co.pt / Portugal em LInha (17 February 2006). "Notícias do Brasil | Noticias do Brasil, Portugal e países de língua portuguesa e comunidades portuguesas". Noticiaslusofonas.com. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- "Venezuela - Inmigración 2017". datosmacro.com.

- "Country-of-birth database". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Archived from the original (XLS) on 11 May 2005. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- "Étrangers : statistiques 2017". www.sem.admin.ch.

- "CBS Statline". Statline.cbs.nl. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- "Population par subdivision territoriale et selon la nationalité 2001" (in French). Statec. Retrieved 1 July 2007.

- Macao Country Study Guide Volume 1 Strategic Information and Developments. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- (in Portuguese)Sidney Arnold Pakeman, "Ceylon", Praeger, 1964

- (in Portuguese)

- Veloso, Ricardo (1 June 2002). "Portugueses na Austrália" [Portuguese in Australia] (in Portuguese). imigrantes.no.sapo.pt. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- Emigração, Observatório da. "Observatório da Emigração". Observatorioemigracao.secomunidades.pt. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- "Statistics Portugal - Web Portal". www.ine.pt.

- "Brasil: 500 anos de povoamento" [Brazil: 500 years of settlement] (in Portuguese). IBGE. Archived from the original on 23 September 2009. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- Pinto Venâncio, Renato (2000). "Presença portuguesa: de colonizadores a imigrantes" [Portuguese presence: from settlers to immigrants] (in Portuguese). IBGE. Archived from the original on 24 November 2002.

- History of Immigration to the United States#Population in 1790

- "Desmundo de Alain Fresnot, o Brasil no século XVI". ensinarhistoria. 27 February 2015. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- "Desmundo by Ana Miranda (1996)". companhiadasletras.com.br. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- "Desmundo by Ana Miranda". companhiadasletras.com.br. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- Telfer (1932), p. 184.

- Bethell (1984), p. 47.

- Ribeiro, Darcy. O Povo Brasileiro, Companhia de Bolso, fourth reprint, 2008 (2008)

- "A Integração social e económica dos emigrantes portugueses no Brasil" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- "Retrato Molecular- Genética". Ich.unito.com. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- Do outro lado do Atlântico: um século de imigração italiana no Brasil. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- "A integração social e económica dos imigrantes portugueses no Brasil nos finais do século xix e no século xx" (PDF). Analisesocial.ics.ul.pt. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- Reis, João José (2000). "Evolução da população brasileira segundo a cor" [Evolution of the Brazilian population according to colour] (in Portuguese). Rio de Janeiro: IBGE. Archived from the original on 5 March 2001. Retrieved 21 November 2006.

- Carvalho, R., Pelos mesmos direitos do imigrante, 2003 Archived 12 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Observatório da Imprensa from the State University of Campinas (Brazil).

- Saloum de Neves Manta F, Pereira R, Vianna R, Rodolfo Beuttenmüller de Araújo A, Leite Góes Gitaí D, Aparecida da Silva D, et al. (2013). "Revisiting the genetic ancestry of Brazilians using autosomal AIM-Indels". PLOS ONE. 8 (9): e75145. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...875145S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0075145. PMC 3779230. PMID 24073242.

- Lima-Costa MF, Rodrigues LC, Barreto ML, Gouveia M, Horta BL, Mambrini J, et al. (April 2015). "Genomic ancestry and ethnoracial self-classification based on 5,871 community-dwelling Brazilians (The Epigen Initiative)". Scientific Reports. 5 (1): 9812. Bibcode:2015NatSR...5E9812.. doi:10.1038/srep09812. PMC 5386196. PMID 25913126.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

.png)