Fishing in Portugal

Fishing is a major economic activity in Portugal. The country has a long tradition in the sector, and is among the countries in the world with the highest fish consumption per capita.[1] Roman ruins of fish processing facilities were found across the Portuguese coast. Fish has been an important staple for the entire Portuguese population, at least since the Portuguese Age of Discovery.

The Portuguese fishing sector is divided into various subsectors, which in turn are divided between industrial fishing and artisanal fishing. According to trade union sources, over 50% of fishing workers work in the artisanal area. There are a variety of trade unions and employers' organisations representing sectoral and regional interests.

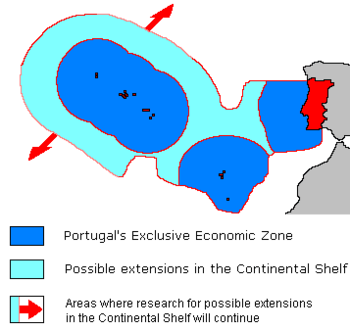

Portugal's Exclusive Economic Zone, a sea zone over which the Portuguese have special rights over the exploration and use of marine resources, has 1,727,408 km2. This is the third-largest Exclusive Economic Zone of the European Union and the eleventh-largest in the world.

Overview

The fishing sector in Portugal faced deep structural changes in terms of both the volume of its business and its working conditions since adhesion to the European Economic Community in 1986. The fishing fleet dropped from 12,299 vessels of all kinds in 1994 to 10,933 in 1999, while the number of registered fishing workers fell from 31,721 to 27,191. The volume of imported fish increased by 31% from 1990 to 1999, whereas exports decreased by 0.4% over the same period.[2]

In 1997, 4,932 people were registered as employees in the fishing sector.[3] In 2004, there were 10,089 vessels registered with a total size of 112,978 GT and a total power of 391 006 kW. These numbers indicate a reduction in overall fleet size since 1998 of approximately 9.9% in number, 1.5% in GT and 0.8% in power. Total catches fell from 224,000 tonnes in 1998 to 140,000 tonnes in 2004, a 38% decrease.

As laid out in its Common Fisheries Policy, the European Union is seeking to establish a policy that determines priorities which will contribute to a sustainable balance between fisheries resources and their exploitation; increase the competitiveness of fishing enterprises and organisations; and develop viable enterprises. The EU has been paying special attention to the situation in Portugal both because of the characteristics of the Portuguese coastal area and the type of vessel used there. The Portuguese fishing fleet has changed significantly, both in size and in character, in order to adjust fishing capacity to the potential of national, EU, non-EU and international waters.

Reflecting the current status of the national resources and restricted access to foreign fishing grounds, re-dimensioning of the fleet is part of the renovation and modernization process. During the 1990s and 2000s, new fishing vessels, with improved on-board fish conservation methods, automated work systems, and electronic navigation and fish detection systems, were gradually introduced to replace the ageing fishing vessels from the 1980s and before.

History

Roman ruins of fish processing facilities were found across the Portuguese coast. Garum (a type of fermented fish sauce) of Lusitania (present-day Portugal) was highly prized in Rome. It was shipped to Rome directly from the harbour of Lacobriga (present-day Lagos). The fishing and fish processing industry was so important in the territory that ruins of a former Roman garum factory can be even visited today in the downtown of Lisbon's old quarter.[4]

Fish has been an important staple for the entire Portuguese population at least since the Portuguese Age of Discovery. The Portuguese population is among the world's largest per capita fish consumers.[1] Portuguese cuisine includes a variety of fish and other seafood-based dishes, some of them renowned internationally.

Resource management and regulation

The main institution responsible for fisheries management is the Directorate-General of Fisheries and Aquaculture (DGPA), in association with the Assistant-Secretariat of State and the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forests. The Instituto Nacional dos Recursos Biológicos (INRB), as well as the Producer Organizations and Shipowner's Associations, are consulted and have an advisory role in the decision-making process.

INRB is also responsible for fish stock assessments within the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) and the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO) frameworks. INRB uses information collected during research surveys and in fishing ports, and also the catch statistics provided by DGPA. At a national level, INRB has also the role of proposing technical measures to protect and maintain fish stocks.

Marine fisheries

The Portuguese fishing industry is fairly large and diversified. Fishing vessels classified according to the area in which they operate, can be divided into local fishing vessels, coastal fishing vessels and long-distance fishing vessels.

The local fleet is mainly composed of small traditional vessels (less than 5 GRT), comprising, in 2004, 87% of the total fishing fleet and accounting for 8% of the total tonnage. These vessels are usually equipped to use more than one fishing method, such as hooks, gill nets and traps, and constitute the so-called polyvalent segment of the fleet. Their physical output is low but reasonable levels of income are attained by virtue of the high commercial value of the species they capture: octopus, black scabbardfish, conger, pouting, hake and anglerfish. Purse seine fishing is also part of the local fleet and has, on the mainland, only one target species: the sardine. This fishery represents 37% of total landings.

The coastal fishing fleet accounted for only 13% of vessels but had the largest GRT (93%). These vessels operate in areas farther from the coast, and even outside the Portugal's Exclusive Economic Zone. The coastal fishing fleet comprises polyvalent, purse seine and trawl fishing vessels. The trawlers operate only on the mainland shelf and target demersal species such as horse mackerel, blue whiting, octopus and crustaceans. The crustacean trawling fishery targets Norway lobster, red shrimp and deepwater rose shrimp.

The most important fish species landed in Portugal in 2004 were sardine, mackerel and horse mackerel, representing 37%, 9% and 8% of total landings by weight, and 13%, 1% and 8% of total value, respectively. Molluscs accounted for only 12% of total landings in weight, but 22% of total landings in value. Crustaceans were 0.6% of the total landings by weight and 5% by value.

Fishing in foreign waters has decreased considerably since 1998, after the end of the fisheries agreement with Morocco and the renegotiation of the agreement with Mauritania. A new fisheries agreement between EU and Morocco has been reached, and started in March 2006, after a 7-year interval. In 1999, 40 Portuguese vessels were fishing in Moroccan waters, making Morocco the second-largest foreign fisheries ground at that time.

In 2004, 15% of the total landings were from international waters from 59 registered vessels, mainly from the northwest Atlantic, northeast Atlantic (Norway, Svalbard, Spain and Greenland since 2003) and the central Atlantic (Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, Senegal, Mauritania). In the northwest Atlantic, redfish was the most important species, with 50% of total catches, while in Spain it was sardine and horse mackerel, with 36%. Off Norway and Svalbard, cod (bacalhau in Portuguese) was the most important species, accounting for 82% of total catches, while from Greenland, redfish was the only species landed. Bacalhau is indeed one of the most popular fishes used in Portuguese cuisine, along with sardine and tuna.

The main landing sites in Portugal (including Azores and Madeira), according to total landings in weight by year, are the harbours of Matosinhos, Peniche, Olhão, Sesimbra, Figueira da Foz, Sines, Portimão and Madeira.

Management applied to main fisheries

The main objective of the national fisheries policy, particularly since 2002, is to maintain the sustainability of the sector and reverse the negative tendency of recent years. To achieve this objective, several measures have been adopted to promote recovery and stabilization of the fishing industry. At the same time, fleet renewal and modernization has been promoted in order to reduce production costs and improve work safety.

Structural modernization of the fishing industry, as well as the processing industry and the aquaculture sector, are also promoted within the present fisheries management plan. These objectives are in accordance with those established by the EU in the Common Fishery Policy. The present national management system includes the establishment of annual quotas for some species and fishing areas, the application of technical conservation measures, and limitation of fishing effort.

Input control

Fishing effort is controlled by a licensing system, where acquisition, construction or modification of vessels requires prior authorization. The use of certain fishing methods is also subject to prior authorization and annual licensing. The objective is to allow the modernization of the fishing fleet without increased fishing effort, by authorizing the construction of new vessels only as replacement of others; improving working conditions; and promoting conservation measures by encourage the use of less predatory fishing gear.

Output controls

There are species subject to quotas in national waters. Quotas can be allocated to individual vessels, as is the case for vessels operating in North Atlantic Fishery Organization (NAFO) and Norwegian fishing grounds; or to groups of vessels, as is the case for the purse seine fishery, where sardine catch limits are divided among Producer Organizations. Individual vessel quotas are also transferable within a shipowner's fleet to facilitate flexible management and therefore maximum utilization of these quotas.

Inland fisheries

In 2004, 63 t of fish were landed by inland fisheries, with a value of US$642 000. The main species landed were shad (Alosa sp.), lamprey (Lampetra fluviatilis) and eels, with 49%, 29% and 16% of total landings from this fishery, respectively. Regarding fisheries management, purse-seine nets, bottom trawl, gill nets (except when targeting lamprey) and gear that uses tidal movements are prohibited in inland waters.

There are also limitations on fishing areas and gear characteristics (mesh and gear size, amongst others). Recreational fishing is common and popular in inland fresh water streams, lakes, reservoirs and rivers. Every recreational fishing enthusiast desiring to use those kinds of national water resources for fishing, must respect rules and be aware of several limitations. A yearly individual fee must be paid to the state for fishing in suitable inland or oceanic waters.

Aquaculture

Until the mid-1980s, aquaculture production consisted of freshwater trout and bivalves bottom culture in tidal estuaries. However, marine aquaculture production showed an overall increase at the beginning of the 1990s, followed by a period of some fluctuation. Total production was 7 829 t in 2003, and consisted mainly of grooved carpet shell (Ruditapes decussatus) (3 007 t), mussels (280 t), oyster (425 t), seabream (1 429 t) and seabass (1 384 t) from marine units; and trout (333 t) from freshwater units.

The objective of the national fisheries policy regarding aquaculture is to increase production and product diversity, but also to increase product quality, in order to improve the competitive position of the sector. Structural modernization of the aquaculture sector is also promoted within the present fisheries management plan. These objectives are in accordance with those established by the European Union in the Common Fisheries Policy, and in particular with the 2002 Strategy for the Sustainable Development of European Aquaculture, which promotes environmental, economic and social sustainability.

One of the main aquaculture projects of Portugal is the Pescanova's production centre in Mira, Centro region.[5] The southern Portuguese region of the Algarve is also a major aquaculture centre.

Fish processing industry

There are many canned fish processing plants across Portugal, producing under different trademarked brands which are mostly exported. The mainland's principal ports specialized in canning small pelagic fish, most of which sardine, are Matosinhos-Póvoa de Varzim area, Peniche, and Olhão. In the Azores, the canned tuna fish industry is predominant, and most of the production is almost exclusively exported.

A diversification drive is being attempted with the development of black scabbardfish canning industry, a barely exploited resource on the islands. Major fish processing companies include Briosa, Cofaco, Cofisa, Conserveira do Sul, Conservas Ramirez (the world's oldest canned fish producer still in operation), Fábrica de Conservas da Murtosa, Conservas Portugal Norte and the Portuguese branch of Pescanova. Portuguese processed fish products are exported through several companies under a number of different brands and registered trademarks like Ramirez, Bom Petisco, Briosa Gourmet, Combate, Comur, Conserveira, General, Inês, Líder, Manná, Murtosa, Pescador, Pitéu, Porthos, Tenório, Torreira, and Vasco da Gama.

Fish consumption

Portugal, as an Atlantic country and an historical seafaring nation, has a long tradition in the sector of fishing. It is among the countries in the world with the highest fish consumption per capita.[1]

Species like the sardine, Atlantic mackerel, tuna, and the European hake are important for the Portuguese commercial capture fisheries. Other, widely used species in Portuguese cuisine is the cod, known in Portugal as bacalhau. Salt cod has been produced for at least 500 years, since the time of the European discoveries. Before refrigeration, there was a need to preserve the codfish; drying and salting are ancient techniques to keep many nutrients and the process makes the codfish tastier.

The Portuguese tried to use this method of drying and salting several fishes from their waters, but the ideal fish came from much further north. With the "discovery" of Newfoundland in 1497, Portuguese fishermen started fishing its cod-rich Grand Banks. Thus, bacalhau became a staple of the Portuguese cuisine, nicknamed fiel amigo (faithful friend). From the 18th century the town of Kristiansund in Norway became an important place of producing bacalao or klippfish, which is also exported to Portugal.

Education, training and research in fishing

In Portugal, there are several vocational and higher education institutions devoted to the teaching of fishing, fisheries, oceanography, marine biology and marine science in general. For example, the state-run polytechnic institute Instituto Politécnico de Leiria at Peniche, through its Escola Superior de Turismo e Tecnologia do Mar de Peniche, has a school of marine technologies awarding bachelor's and master's degrees in these subjects.

There are also a number of universities awarding bachelor's, masters' and doctorate degrees in varied marine science subfields, as well as making research and development work. The marine biology and marine sciences degrees awarded by the Marine and Environmental Sciences Faculty of the University of the Algarve are among the most prestigious in the country. The Instituto Nacional dos Recursos Biológicos (INRB) is the national research institute for agriculture and fisheries.

See also

- Agriculture in Portugal

- Economy of Portugal

- Portugal's Exclusive Economic Zone

References

SILVA, A. J. M. (2015), The fable of the cod and the promised sea. About Portuguese traditions of bacalhau, in BARATA, F. T- and ROCHA, J. M. (eds.), Heritages and Memories from the Sea, Proceedings of the 1st International Conference of the UNESCO Chair in Intangible Heritage and Traditional Know-How: Linking Heritage, 14–16 January 2015. University of Evora, Évora, pp. 130–143. PDF version

- (in Portuguese) PESSOA, M.F.; MENDES, B.; OLIVEIRA, J.S. CULTURAS MARINHAS EM PORTUGAL, "O consumo médio anual em produtos do mar pela população portuguesa, estima-se em cerca de 58,5 kg/ por habitante sendo, por isso, o maior consumidor em produtos marinhos da Europa e um dos quatro países a nível mundial com uma dieta à base de produtos do mar."

- Pescas Portuguesas e Datapescas nº 43, December 1999, Ministry of Agriculture, Rural Development and Fisheries

- Quadros de Pessoal, 1997

- Fundação Millennium bcp Fundação Millennium bcp - Núcleo Arqueológico

- (in Portuguese) José Carlos Silva, Comissário Europeu em Mira para inaugurar Pescanova, in Diário de Coimbra (June 14, 2009).

.png)