Gallaeci

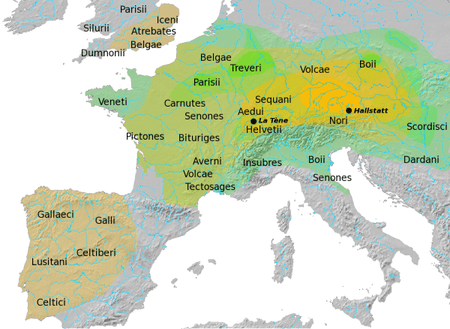

The Gallaeci, Callaeci or Callaici were a large Celtic tribal federation who inhabited Gallaecia, the north-western corner of Iberia, a region roughly corresponding to what is now northern Portugal, Galicia, western Asturias and western Castile and León in Spain, before and during the Roman period.[1] They spoke a Q-Celtic language related to Northeastern Hispano-Celtic, usually called Gallaic, Gallaecian, or Northwestern Hispano-Celtic.[2][3][4] The region was annexed by the Romans in the time of Caesar Augustus during the Cantabrian Wars, a war which initiated the assimilation of the Gallaeci into Latin culture.

History

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Galicia |

|

|

| Timeline |

The fact that the Gallaeci did not adopt writing until contact with the Romans constrains the study of their earlier history. However, early allusions to this people are present in ancient Greek and Latin authors prior to the conquest, which allows the reconstruction of a few historical events of this people since the second century BC.

Thanks to Silius Italicus, it is known that between the years 218 and 201 BC, during the Second Punic War, some Gallaecian troops were involved in the fight in the ranks of Carthaginian Hannibal against the Roman army of Scipio Africanus. Silius described them as a contingent combined with Lusitanian forces and led by a commander named Viriathus, and gave a short description of them and their military tactics:[5]

[…] Fibrarum et pennae divinarumque sagacem flammarum misit dives Gallaecia pubem, barbara nunc patriis ululantem carmina linguis, nunc pedis alterno percussa verbere terra ad numerum resonas gaudentem plauder caetras […]

Rich Gallaecia sent its youths, wise in the knowledge of divination by the entrails of beasts, by feathers and flames, now howling barbarian songs in the tongues of their homelands, now alternately stamping the ground in their rhythmic dances until the ground rang, and accompanying the playing with sonorous shields.

The first known military conflict between Gallaeci and Romans is mentioned in Appian of Alexandria's book Iberiké, narrating events during the Lusitanian War (155–139 BC). In 139 BC, after being cheated by the Lusitanian chief Viriatus (not to be confused with the aforementioned), Quintus Servilius Caepio's army devastated few Gallaecian and Vettonian regions. The attack on these Southern Gallaecian peoples, near the border with Vettones, was punishment for Gallaecian support to Lusitanians. Orosius later mentioned that Brutus surrounded the Gallaeci, who were unaware, and crushed sixty thousand of them who had come to the assistance of the Lusitani. The Romans were victorious only after a desperate and difficult battle and fifty thousand of them were slain in that battle, six thousand were captured, and only some escaped.[6] The legates Antistius and Firmius fought appalling battles and subdued the further parts of Gallaecia, forested and mountainous and bordering the Atlantic.[7]

Archaeology

Archaeologically, the Gallaeci were a local Atlantic Bronze Age people (1300–700 BC). During the Iron Age they received several influences, including from other Iberian cultures, and from central-western Europe (Hallstatt and, to a lesser extent, La Tène culture), and from the Mediterranean (Phoenicians and Carthaginians). The Gallaeci dwelt in hill forts (locally called castros), and the archaeological culture they developed is known by archaeologists as "Castro culture", a hill-fort culture with round houses.

The Gallaecian way of life was based in land occupation especially by fortified settlements that are known in Latin language as "castrum" (hillforts) or oppida (citadels), being able to vary its size from a small village of less than one hectare (more common in the northern territory), and great walled citadels with more than 10 hectares denominated oppida being these latter more common in the Southern half of their traditional settlement around the Ave river. This livelihood in hillforts was common throughout Europe during the Bronze and Iron Ages, getting in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula, the name of 'Castro culture" (Castrum culture) or "hillfort's culture", which alludes to this type of settlement prior to the Roman conquest. However, several Gallaecian hillforts continued to be inhabited until the 5th century AD.

These fortified villages or cities tended to be located in the hills, and occasionally rocky promontories and peninsulas near the seashore, as it improved visibility and control over territory. These settlements were strategically located for a better control of natural resources, including mineral ores such as iron. The Gallaecian hillforts and oppidas maintained a great homogeneity and presented clear commonalities. The citadels, however, functioned as city-states and could have specific cultural traits.

Political-territorial organization

The Gallaecian political organization is not known with certainty, but it is very probable that they were divided into small independent states that comprised in its interior a great number of small hillforts, these stated were ruled by local petty kings, which the Romans called princeps as in other parts of Europe. Commonalities, including political ones, were effective and support between the cities that attempted to halt the Roman conquest of the Gallaecian lands and an almost successful attempt by Gallaecian warriors to drive the Romans out of Lusitania through the destruction of Roman settlements reaching the south of the Iberian Peninsula.

Some of the most famous cities were the wealthy and famously resistant city of Cinania, the notable city of Avobriga and its neighboring citadel, Lambriaca, which allied with Rome, but became the leader for the Gallaeci resistance. The ruins of these cities may still exist today in Northern Portugal, although the location of each is still not attributed with certainty to some of the main Castro culture ruins.

Each Gallaecian considered himself also a member of the hillfort where lived (according to the most common interpretation of the reversed C of epigraphy later) and the state / people to whom they belonged, and that the Romans called populus, among all some of them left us their names: Arrotrebae, Albion, Praestamarici, Lemavi, etc.

Gallaeci tribes:

|

|

|

|

Origin of the name

The Romans named the entire region north of the Douro, where the Castro culture existed, in honour of the castro people that settled in the area of Calle — the Callaeci. The Romans established a port in the south of the region which they called Portus Calle, today's Porto, in northern Portugal.[8] When the Romans first conquered the Callaeci they ruled them as part of the province of Lusitania but later created a new province of Callaecia (Greek: Καλλαικία) or Gallaecia.

The names "Callaici" and "Calle" are the origin of today's Gaia, Galicia, and the "Gal" root in "Portugal", among many other placenames in the region.

Gallaecian language

Gallaecian or Gallaic was a Q-Celtic language or group of languages or dialects, closely related to Celtiberian, spoken at the beginning of our era in the north-western quarter of the Iberian Peninsula, more specifically between the west and north Atlantic coasts and an imaginary line running north–south and linking Oviedo and Mérida.[9][10] Just like it is the case for Illyrian or Ligurian languages, its corpus is composed by isolated words and short sentences contained in local Latin inscriptions, or glossed by classic authors, together with a considerable number of names – anthroponyms, ethnonyms, theonyms, toponyms – contained in inscriptions, or surviving up to date as place, river or mountain names. Besides, many of the isolated words of Celtic origin preserved in the local Romance languages could have been inherited from these Q-Celtic dialects.

Gallaecian deities

Through the Gallaecian-Roman inscriptions, is known part of the great pantheon of Gallaecian deities, sharing part not only by other Celtic or Celticized peoples in the Iberian Peninsula, such as Astur — especially the more Western — or Lusitanian, but also by Gauls and Britons among others. This will highlight the following:

- Bandua: Gallaecian God of War, similar to the Roman god, Mars. Great success among the Gallaeci of Braga.

- Berobreus: god of the Otherworld and beyond. The largest shrine dedicated to Berobreo documented until now, stood in the fort of the Torch of Donón (Cangas), in the Morrazo's Peninsula, front of the Cíes Islands.

- Bormanicus: god of hot springs similar to the Gaulish god, Bormanus.

- Nabia: goddess of waters, of fountains and rivers. In Galicia and Portugal still nowadays, numerous rivers that still persist with his name, as the river Navia, ships and in northern Portugal there is the Idol Fountain, dedicated to the goddess ship.

- Cossus, warrior god, who attained great popularity among the Southern Gallaeci, was one of the most revered gods in ancient Gallaecia. Several authors suggest that Cosso and Bandua are the same God under different names.

- Reue, associated with the supreme God hierarchy, justice and also death.

- Lugus, or Lucubo, linked to prosperity, trade and craft occupations. His figure is associated with the spear. It is one of gods most common among the Celts and many, many place names derived from it throughout Europe Celtic Galicia (Galicia Lucus Latinized form) to Loudoun (Scotland), and even the naming of people as Gallaecia Louguei .

- Coventina, goddess of abundance and fertility. Strongly associated with the water nymphs, their cult record for most Western Europe, from England to Gallaecia.

- Endovelicus (Belenus), god of prophecy and healing, showing the faithful in dreams.

See also

- Albiones

- Astures

- Cantabri

- Celtici

- Gallaecia

- Gallaecian language

- Galician Institute for Celtic Studies

- Prehistoric Iberia

- Pre-Roman peoples of the Iberian Peninsula

Notes

- cf. Koch, John T. (ed.) (2006). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 790. ISBN 1-85109-440-7.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "In the northwest of the Iberian Peninula, and more specifically between the west and north Atlantic coasts and an imaginary line running north-south and linking Oviedo and Merida, there is a corpus of Latin inscriptions with particular characteristics of its own. This corpus contains some linguistic features that are clearly Celtic and others that in our opinion are not Celtic. The former we shall group, for the moment, under the label northwestern Hispano-Celtic. The latter are the same features found in well-documented contemporary inscriptions in the region occupied by the Lusitanians, and therefore belonging to the variety known as LUSITANIAN, or more broadly as GALLO-LUSITANIAN. As we have already said, we do not consider this variety to belong to the Celtic language family." Jordán Colera 2007: p.750

- Luján Martínez, Eugenio R. (3 May 2006). "The Language(s) of the Callaeci". E-keltoi. 6: The Celts in the Iberian Peninsula: 689–714. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- ' In the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula, and more specifically between the west and north Atlantic coasts and an imaginary line running north-south and linking Oviedo and Mérida, there is a corpus of Latin inscriptions with particular characteristics of its own. This corpus contains some linguistic features that are clearly Celtic and others that in our opinion are not Celtic. The former we shall group, for the moment, under the label northwestern Hispano-Celtic.'Jordán Cólera, Carlos (16 March 2007). "Celtiberian" (PDF). E-keltoi. 6: The Celts in the Iberian Peninsula: 750. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- Silius Italicus, Punica, 3

- Orosius. A History, against the Pagans - Book 5.

- Orosius. A History, against the Pagans - Book 6.

- "Roteiro Arqueológico" (PDF). Eixo Atlântico. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-02-15. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Jordán Colera 2007: 750

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 481. ISBN 9781851094400.

References

- Coutinhas, José Manuel (2006), Aproximação à identidade etno-cultural dos Callaici Bracari, Porto.

- Queiroga, Francisco (1992), War and Castros, Oxford.

- Silva, Armando Coelho Ferreira da (1986), A Cultura Castreja no Noroeste de Portugal, Porto.

- Pena Granha, André (2014)

"A CULTURA CASTREXA INEXISTENTE. CONSTITUIÇÃO POLÍTICA DAS GALAICAS TREBA". Cátedra, Pontedeume