World Trade Center (1973–2001)

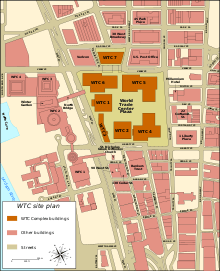

The original World Trade Center was a large complex of seven buildings in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan, New York City, United States. It opened on April 4, 1973, and was destroyed in 2001 during the September 11 attacks. At the time of their completion, the Twin Towers—the original 1 World Trade Center, at 1,368 feet (417 m); and 2 World Trade Center, at 1,362 feet (415.1 m)—were the tallest buildings in the world. Other buildings in the complex included the Marriott World Trade Center (3 WTC), 4 WTC, 5 WTC, 6 WTC, and 7 WTC. The complex contained 13,400,000 square feet (1,240,000 m2) of office space.

| World Trade Center | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg) The original complex in March 2001. The tower on the left, with antenna spire, was 1 WTC. The tower on the right was 2 WTC. All seven buildings of the WTC complex are partially visible. The red granite-clad building left of the Twin Towers was the original 7 World Trade Center. In the background is the East River. | |||||||||||||||||||

%26groups%3D_571ec6041fd8253c8da42b782c03b8ade66345dd.svg)

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Record height | |||||||||||||||||||

| Tallest in the world from 1970 to 1973[I] | |||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Empire State Building | ||||||||||||||||||

| Surpassed by | Willis Tower | ||||||||||||||||||

| General information | |||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Destroyed | ||||||||||||||||||

| Architectural style | Structural expressionism | ||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Lower Manhattan, New York City | ||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 40°42′42″N 74°00′45″W | ||||||||||||||||||

| Groundbreaking | August 5, 1966 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Construction started |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Topped-out |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Completed |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Opening |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Inaugurated | April 4, 1973 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Destroyed | September 11, 2001 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | Port Authority of New York and New Jersey | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Design and construction | |||||||||||||||||||

| Architect |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Developer | Port Authority of New York and New Jersey | ||||||||||||||||||

| Engineer | Worthington, Skilling, Helle & Jackson,[2] Leslie E. Robertson Associates | ||||||||||||||||||

| Main contractor | Tishman Realty & Construction Company | ||||||||||||||||||

| References | |||||||||||||||||||

| I. ^ World Trade Center at Emporis [3][4] | |||||||||||||||||||

The core complex was built between 1966 and 1975, at a cost of $400 million (equivalent to $2.27 billion in 2018).[5] During its existence, the World Trade Center experienced several major incidents, including a fire on February 13, 1975,[6] a bombing on February 26, 1993,[7] and a bank robbery on January 14, 1998.[8] In 1998, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey decided to privatize it by leasing the buildings to a private company to manage. It awarded the lease to Silverstein Properties in July 2001.[9]

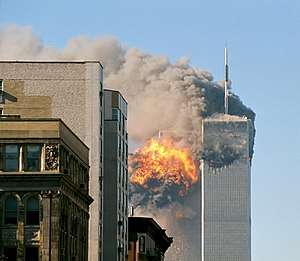

On the morning of September 11, 2001, Al-Qaeda-affiliated hijackers flew two Boeing 767 jets into the North and South Towers within minutes of each other; two hours later, both towers collapsed. The attacks killed 2,606 people in and within the vicinity of the towers, as well as all 157 on board the two aircraft.[10] Falling debris from the towers, combined with fires that the debris initiated in several surrounding buildings, led to the partial or complete collapse of all the buildings in the complex, and caused catastrophic damage to ten other large structures in the surrounding area.

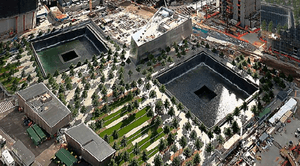

The cleanup and recovery process at the World Trade Center site took eight months, during which the remains of the other buildings were demolished. A new World Trade Center complex is being built with six new skyscrapers and several other buildings, many of which are complete. A memorial and museum to those killed in the attacks, a new rapid transit hub, and an elevated park have been opened. One World Trade Center, the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere at 1,776 feet (541 m) and the lead building for the new complex, was completed in November 2014.

During its existence, the World Trade Center was an icon of New York City.[11] It had a major role in popular culture and according to one estimate was depicted in 472 films. Following the World Trade Center's destruction, mentions of the complex were altered or deleted, and several dozen "memorial films" were created.[12]

Before the World Trade Center

Site

The western portion of the World Trade Center site was originally under the Hudson River. The shoreline was in the vicinity of Greenwich Street, which is closer to the site's eastern border. It was on this shoreline, close to the intersection of Greenwich and the former Dey Street, that Dutch explorer Adriaen Block's ship, Tyger, burned to the waterline in November 1613, stranding him and his crew and forcing them to overwinter on the island. They built the first European settlement in Manhattan. The remains of the ship were buried under landfill when the shoreline was extended beginning in 1797 and were discovered during excavation work in 1916. The remains of a second eighteenth century ship were discovered in 2010 during excavation work at the site. The ship, believed to be a Hudson River sloop, was found just south of where the Twin Towers stood, about 20 feet (6.1 m) below the surface.[13]

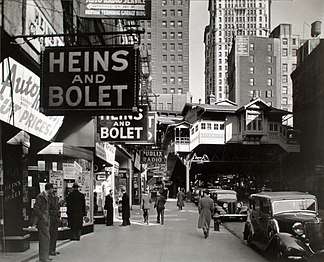

Later, the area became New York City's Radio Row, which existed from 1921 to 1966. The neighborhood was a warehouse district in what is now Tribeca and the Financial District. Harry Schneck opened City Radio on Cortlandt Street in 1921, and eventually the area held several blocks of electronics stores, with Cortlandt Street as its central axis. The used radios, war surplus electronics (e.g., AN/ARC-5 radios), junk, and parts were often piled so high they would spill out onto the street, attracting collectors and scroungers. According to a business writer, it also was the origin of the electronic component distribution business.[14]

Establishment of World Trade Center

The idea of establishing a World Trade Center in New York City was first proposed in 1943. The New York State Legislature passed a bill authorizing New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey to begin developing plans for the project,[15] but the plans were put on hold in 1949.[16] During the late 1940s and 1950s, economic growth in New York City was concentrated in Midtown Manhattan. To help stimulate urban renewal in Lower Manhattan, David Rockefeller suggested that the Port Authority build a World Trade Center there.[17]

Plans for the use of eminent domain to remove the shops in Radio Row bounded by Vesey, Church, Liberty, and West Streets began in 1961 when the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey was deciding to build the world's first world trade center. They had two choices: the east side of Lower Manhattan, near the South Street Seaport; or the west side, near the Hudson and Manhattan Railroad (H&M) station, Hudson Terminal.[18] Initial plans, made public in 1961, identified a site along the East River for the World Trade Center.[19] As a bi-state agency, the Port Authority required approval for new projects from the governors of both New York and New Jersey. New Jersey Governor Robert B. Meyner objected to New York getting a $335 million project.[20] Toward the end of 1961, negotiations with outgoing New Jersey Governor Meyner reached a stalemate.[21]

At the time, ridership on New Jersey's H&M Railroad had declined substantially from a high of 113 million riders in 1927 to 26 million in 1958 after new automobile tunnels and bridges had opened across the Hudson River.[22] In a December 1961 meeting between Port Authority director Austin J. Tobin and newly elected New Jersey Governor Richard J. Hughes, the Port Authority offered to take over the H & M Railroad. They also decided to move the World Trade Center project to the Hudson Terminal building site on the west side of Lower Manhattan, a more convenient location for New Jersey commuters arriving via PATH.[21] With the new location and the Port Authority's acquisition of the H&M Railroad, New Jersey agreed to support the World Trade Center project.[23] As part of the deal, the Port Authority renamed the H&M "Port Authority Trans-Hudson", or PATH for short.[24]

To compensate Radio Row business owners for their displacement, the Port Authority gave each business $3,000, without regard to how long the business had been there or how prosperous it was.[25] The Port Authority began purchasing properties in the area for the World Trade Center by March 1965,[26] and demolition of Radio Row began in March 1966.[27] It was completely demolished by the end of the year.[28]

Approval was also needed from New York City Mayor John Lindsay and the New York City Council. Disagreements with the city centered on tax issues. On August 3, 1966, an agreement was reached whereby the Port Authority would make annual payments to the City in lieu of taxes for the portion of the World Trade Center leased to private tenants.[29] In subsequent years, the payments would rise as the real estate tax rate increased.[30]

Design, construction, and criticism

Design

On September 20, 1962, the Port Authority announced the selection of Minoru Yamasaki as lead architect and Emery Roth & Sons as associate architects.[31] Yamasaki devised the plan to incorporate twin towers. His original plan called for the towers to be 80 stories tall,[32] but to meet the Port Authority's requirement for 10,000,000 square feet (930,000 m2) of office space, the buildings would each have to be 110 stories tall.[33]

Yamasaki's design for the World Trade Center, unveiled to the public on January 18, 1964, called for a square plan approximately 208 feet (63 m) in dimension on each side.[32][34] The buildings were designed with narrow office windows 18 inches (46 cm) wide, which reflected Yamasaki's fear of heights as well as his desire to make building occupants feel secure.[35] His design included building facades clad in aluminum-alloy.[36] The World Trade Center was one of the most-striking American implementations of the architectural ethic of Le Corbusier and was the seminal expression of Yamasaki's gothic modernist tendencies.[37] He was also inspired by Arabic architecture, elements of which he incorporated in the building's design, having previously designed Saudi Arabia's Dhahran International Airport with the Saudi Binladin Group.[38][39]

A major limiting factor in building height is the issue of elevators; the taller the building, the more elevators are needed to service it, requiring more space-consuming elevator banks.[40] Yamasaki and the engineers decided to use a new system with two "sky lobbies"—floors where people could switch from a large-capacity express elevator to a local elevator that goes to each floor in a section. This system, inspired by the local-express train operation used in New York City's subway system,[41] allowed the design to stack local elevators within the same elevator shaft. Located on the 44th and 78th floors of each tower, the sky lobbies enabled the elevators to be used efficiently. This increased the amount of usable space on each floor from 62 to 75 percent by reducing the number of elevator shafts.[42] Altogether, the World Trade Center had 95 express and local elevators.[43]

The structural engineering firm Worthington, Skilling, Helle & Jackson worked to implement Yamasaki's design, developing the framed-tube structural system used in the twin towers.[44] The Port Authority's Engineering Department served as foundation engineers, Joseph R. Loring & Associates as electrical engineers, and Jaros, Baum & Bolles (JB&B) as mechanical engineers. Tishman Realty & Construction Company was the general contractor on the World Trade Center project. Guy F. Tozzoli, director of the World Trade Department at the Port Authority, and Rino M. Monti, the Port Authority's Chief Engineer, oversaw the project.[45] As an interstate agency, the Port Authority was not subject to the local laws and regulations of the City of New York, including building codes. Nonetheless, the World Trade Center's structural engineers ended up following draft versions of New York City's new 1968 building codes.[46]

The framed-tube design, introduced in the 1960s by Bangladeshi-American structural engineer Fazlur Rahman Khan,[47] was a new approach that allowed more open floor plans than the traditional design that distributed columns throughout the interior to support building loads. Each of the World Trade Center towers had 236 high-strength, load-bearing perimeter steel columns which acted as Vierendeel trusses.[48][44] The perimeter columns were spaced closely together to form a strong, rigid wall structure, supporting virtually all lateral loads such as wind loads, and sharing the gravity load with the core columns.[44] The perimeter structure containing 59 columns per side was constructed with extensive use of prefabricated modular pieces, each consisting of three columns, three stories tall, connected by spandrel plates.[49] The spandrel plates were welded to the columns to create the modular pieces off-site at the fabrication shop.[50] Adjacent modules were bolted together with the splices occurring at mid-span of the columns and spandrels. The spandrel plates were located at each floor, transmitting shear stress between columns, allowing them to work together in resisting lateral loads. The joints between modules were staggered vertically, so that the column splices between adjacent modules were not at the same floor.[46] Below 7th floor to the foundation, there were fewer, wider-spaced perimeter columns to accommodate doorways.[49][44]

The core of the towers housed the elevator and utility shafts, restrooms, three stairwells, and other support spaces. The core of each tower was a rectangular area 87 by 135 feet (27 by 41 m) and contained 47 steel columns running from the bedrock to the top of the tower. The large, column-free space between the perimeter and core was bridged by prefabricated floor trusses. The floors supported their own weight as well as live loads, providing lateral stability to the exterior walls and distributing wind loads among the exterior walls.[51] The floors consisted of 4-inch (10 cm) thick lightweight concrete slabs laid on a fluted steel deck. A grid of lightweight bridging trusses and main trusses supported the floors.[49] The trusses connected to the perimeter at alternate columns and were on 6 foot 8 inch (2.03 m) centers. The top chords of the trusses were bolted to seats welded to the spandrels on the exterior side and a channel welded to the core columns on the interior side. The floors were connected to the perimeter spandrel plates with viscoelastic dampers that helped reduce the amount of sway felt by building occupants.

Hat trusses (or "outrigger trusses") located from the 107th floor to the top of the buildings were designed to support a tall communication antenna on top of each building.[49] Only 1 WTC (north tower) actually had an antenna fitted; it was added in 1978.[52] The truss system consisted of six trusses along the long axis of the core and four along the short axis. This truss system allowed some load redistribution between the perimeter and core columns and supported the transmission tower.[49]

The framed-tube design, using steel core and perimeter columns protected with sprayed-on fire resistant material, created a relatively lightweight structure that would sway more in response to the wind compared to traditional structures, such as the Empire State Building that have thick, heavy masonry for fireproofing of steel structural elements.[53] During the design process, wind tunnel tests were done to establish design wind pressures that the World Trade Center towers could be subjected to and structural response to those forces.[54] Experiments also were done to evaluate how much sway occupants could comfortably tolerate; however, many subjects experienced dizziness and other ill effects.[55] One of the chief engineers Leslie Robertson worked with Canadian engineer Alan G. Davenport to develop viscoelastic dampers to absorb some of the sway. These viscoelastic dampers, used throughout the structures at the joints between floor trusses and perimeter columns along with some other structural modifications, reduced the building sway to an acceptable level.[56]

Construction

In March 1965, the Port Authority began acquiring property at the World Trade Center site.[26] Demolition work began on March 21, 1966, to clear thirteen square blocks of low rise buildings in Radio Row for its construction.[27] Groundbreaking for the construction of the World Trade Center took place on August 5, 1966.[57]

The site of the World Trade Center was located on landfill with the bedrock located 65 feet (20 m) below.[58] To construct the World Trade Center, it was necessary to build a "bathtub" with a slurry wall around the West Street side of the site, to keep water from the Hudson River out.[59] The slurry method selected by the Port Authority's chief engineer, John M. Kyle, Jr., involved digging a trench, and as excavation proceeded, filling the space with a "slurry" mixture composed of bentonite and water, which plugged holes and kept groundwater out. When the trench was dug out, a steel cage was inserted and concrete was poured in, forcing the "slurry" out. It took fourteen months for the slurry wall to be completed. It was necessary before excavation of material from the interior of the site could begin.[60] The 1,200,000 cubic yards (920,000 m3) of excavated material were used (along with other fill and dredge material) to expand the Manhattan shoreline across West Street to form Battery Park City.[61][62]

In January 1967, the Port Authority awarded $74 million in contracts to various steel suppliers.[63] Construction work began on the North Tower in August 1968, and construction on the South Tower was under way by January 1969.[64] The original Hudson Tubes, which carried PATH trains into Hudson Terminal, remained in service during the construction process until 1971, when a new station opened.[65] The topping out ceremony of 1 WTC (North Tower) took place on December 23, 1970, while 2 WTC's ceremony (South Tower) occurred on July 19, 1971.[64] Extensive use of prefabricated components helped to speed up the construction process, and the first tenants moved into the North Tower in December 15, 1970, while it was still under construction,[66][4] while the South Tower began accepting tenants in January 1972.[67] When the World Trade Center twin towers were completed, the total costs to the Port Authority had reached $900 million.[68] The ribbon cutting ceremony took place on April 4, 1973.[69]

In addition to the twin towers, the plan for the World Trade Center complex included four other low-rise buildings, which were built in the early 1970s. The 47-story 7 World Trade Center building was added in the 1980s, to the north of the main complex. Altogether, the main World Trade Center complex occupied a 16-acre (65,000 m2) superblock.[70][71]

Criticism

Plans to build the World Trade Center were controversial. Its site was the location of Radio Row, home to hundreds of commercial and industrial tenants, property owners, small businesses, and approximately 100 residents, many of whom fiercely resisted forced relocation.[72] A group of affected small businesses sought an injunction challenging the Port Authority's power of eminent domain.[73] The case made its way through the court system to the United States Supreme Court; it refused to hear the case.[74]

Private real estate developers and members of the Real Estate Board of New York, led by Empire State Building owner Lawrence A. Wien, expressed concerns about this much "subsidized" office space going on the open market, competing with the private sector, when there was already a glut of vacancies.[75][76] The World Trade Center itself was not rented out completely until after 1979 and then only because the complex's subsidy by the Port Authority made rents charged for its office space cheaper than those for comparable space in other buildings.[77] Others questioned whether the Port Authority should have taken on a project described by some as a "mistaken social priority".[78]

The World Trade Center's design aesthetics attracted criticism from the American Institute of Architects and other groups.[36][79] Lewis Mumford, author of The City in History and other works on urban planning, criticized the project, describing it and other new skyscrapers as "just glass-and-metal filing cabinets".[80] The Twin Towers were described as looking similar to "the boxes that the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building came in".[81] Many disliked the twin towers' narrow office windows, which were only 18 inches (46 cm) wide and framed by pillars that restricted views on each side to narrow slots.[35] Activist and sociologist Jane Jacobs argued the waterfront should be kept open for New Yorkers to enjoy.[82]

Some critics regarded the trade center's "superblock", replacing a more traditional, dense neighborhood, as an inhospitable environment that disrupted the complicated traffic network typical of Manhattan. For example, in his book The Pentagon of Power, Lewis Mumford denounced the center as an "example of the purposeless giantism and technological exhibitionism that are now eviscerating the living tissue of every great city".[71]

Complex

The World Trade Center complex housed more than 430 companies that were engaged in various commercial activities.[83] On a typical weekday, an estimated 50,000 people worked in the complex and another 140,000 passed through as visitors.[83] The complex hosted 13,400,000 square feet (1,240,000 m2) of office space,[84][85] and was so large that it had its own zip code: 10048.[86] The towers offered expansive views from the observation deck atop the South Tower and the Windows on the World restaurant on top of the North Tower. The Twin Towers became known worldwide, appearing in numerous movies and television shows as well as on postcards and other merchandise. It became a New York icon, in the same league as the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, and the Statue of Liberty.[87] The World Trade Center was compared to Rockefeller Center, which David Rockefeller's brother Nelson had developed in midtown Manhattan.[88]

North and South Towers

One World Trade Center and Two World Trade Center, commonly referred to as the Twin Towers, were designed by architect Minoru Yamasaki as framed tube structures, which provided tenants with open floor plans, uninterrupted by columns or walls.[89][90] They were the main buildings of the World Trade Center.[64] Construction of the North Tower at One World Trade Center began in 1966 with the South Tower at Two World Trade Center.[91] When completed in 1972, 1 World Trade Center became the tallest building in the world for two years, surpassing the Empire State Building after its 40-year reign. The North Tower stood 1,368 feet (417 m) tall[91] and featured a 362 foot (110 m) telecommunications antenna or mast that was built on the roof in 1978. With this addition, the highest point of the North Tower reached 1,730 feet (530 m).[92] Chicago's Sears Tower, finished in May 1973, reached 1,450 feet (440 m) at the rooftop.[93]

When completed in 1973, the South Tower became the second tallest building in the world at 1,362 feet (415 m). Its rooftop observation deck was 1,362 ft (415 m) high and its indoor observation deck was 1,310 ft (400 m) high.[92] Each tower stood over 1,350 feet (410 m) high, and occupied about 1 acre (4,000 m2) of the total 16 acres (65,000 m2) of the site's land. During a press conference in 1973, Yamasaki was asked, "Why two 110-story buildings? Why not one 220-story building?" His tongue-in-cheek response was: "I didn't want to lose the human scale."[94]

Throughout their existence, the twin towers had more floors (at 110) than any other building.[92] Their floor counts were not matched until the construction of the Sears Tower, and they were not surpassed until the construction of the Burj Khalifa, which opened in 2010.[95][96] Each tower had a total mass of around 500,000 tons.[97]

Austin J. Tobin Plaza

The original World Trade Center had a massive, five-acre plaza which all other buildings, including the Twin Towers centered around. In 1982, the immense plaza between the twin towers was renamed after the man who authorized the construction of the original World Trade Center. Port Authority's late chairman, Austin J. Tobin.[98] During the summer, the Port Authority installed a portable stage, typically backed up against the North Tower within Tobin Plaza for performers.[99] The odd layout for performances was due to the installation of a sculpture in the center of the plaza, which only allowed for about 6,000 fans. [100] For many years, the Plaza was often beset by brisk winds at ground level owing to the Venturi effect between the two towers.[101] Some gusts were so strong that pedestrians' travel had to be aided by ropes.[102] In 1999, the outdoor plaza reopened after undergoing $12 million in renovations. This involved replacing marble pavers with gray and pink granite stones, adding new benches, planters, new restaurants, food kiosks and outdoor dining areas.[103]

Top of the World observation deck

Although most of the space in the World Trade Center complex was off-limits to the public, the South Tower featured a public observation deck on the 107th floor called Top of the World.[104][105] After paying an entrance fee, visitors were required to pass through security checks added after the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.[106] They were then sent to the 107th-floor indoor observatory at a height of 1,310 feet (400 m) by a dedicated express elevator.[104] The exterior columns were narrowed to allow 28 inches of window width between them. The Port Authority renovated the observatory in 1995, then leased it to Ogden Entertainment to operate. Attractions added to the observation deck included a theater showing a film of a helicopter tour around the city.[104] The 107th-floor food court was designed with a subway car theme and featured Sbarro and Nathan's Famous Hot Dogs.[92][107] Weather permitting, visitors could ride two short escalators up from the 107th-floor viewing area to an outdoor platform at a height of 1,377 ft (420 m).[104][108] On a clear day, visitors could see up to 50 miles (80 km).[92] An anti-suicide fence was placed on the roof itself, with the viewing platform set back and elevated above it, requiring only an ordinary railing. This left the view unobstructed, unlike the observation deck of the Empire State Building.[107]

Windows on the World restaurant

Windows on the World, the restaurant on the North Tower's 106th and 107th floors, opened in April 1976. It was developed by restaurateur Joe Baum at a cost of more than $17 million.[109] As well as the main restaurant, two offshoots were located at the top of the North Tower: Hors d'Oeuvrerie (offered a Danish smorgasbord during the day and sushi in the evening) and Cellar in the Sky (a small wine bar).[110] Windows on the World also had a wine school program run by Kevin Zraly, who published a book on the course.[111]

Windows on the World was closed following the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.[109] When it reopened in 1996, the Greatest Bar on Earth and Wild Blue replaced the original restaurant offshoots.[110] In 2000, its last full year of operation, Windows on the World reported revenues of $37 million, making it the highest-grossing restaurant in the United States.[112] The Sky Dive Restaurant, on the 44th floor of the North Tower, was also operated by Windows on the World.[110]

In its last iteration, Windows on the World received mixed reviews. Ruth Reichl, a New York Times food critic, said in December 1996 that "nobody will ever go to Windows on the World just to eat, but even the fussiest food person can now be content dining at one of New York's favorite tourist destinations". She gave the restaurant two out of four stars, signifying a "very good" quality.[113] In his 2009 book Appetite, William Grimes wrote that, "At Windows, New York was the main course".[114] In 2014, Ryan Sutton of Eater.com compared the now-destroyed restaurant's cuisine to that of its replacement, One World Observatory. He said, "Windows helped usher in a new era of captive audience dining in that the restaurant was a destination in itself, rather than a lazy by-product of the vital institution it resided in."[115]

Other buildings

Five smaller buildings stood on the 16-acre (65,000 m2) block.[116] One was the 22-floor hotel, which opened at the southwest corner of the site in 1981 as the Vista Hotel;[117] in 1995, it became the Marriott World Trade Center (3 WTC).[116] Three low-rise buildings (4 WTC, 5 WTC, and 6 WTC), which were steel-framed office buildings, also stood around the plaza.[118] 6 World Trade Center, at the northwest corner, housed the United States Customs Service.[119] 5 World Trade Center was located at the northeast corner above the PATH station, and 4 World Trade Center, located at the southeast corner,[120] housed the U.S. Commodities Exchange.[119] In 1987, construction was completed on a 47-floor office building, 7 World Trade Center, located to the north of the superblock.[121] Beneath the World Trade Center complex was an underground shopping mall. It had connections to various mass transit facilities, including the New York City Subway system and the Port Authority's PATH trains.[122][123]

One of the world's largest gold depositories was located underneath the World Trade Center, owned by a group of commercial banks. The 1993 bombing detonated close to the vault.[124] Seven weeks after the September 11 attacks, $230 million in precious metals was removed from basement vaults of 4 WTC. This included 3,800 100-Troy-ounce 24 carat gold bars and 30,000 1,000-ounce silver bars.[125]

Major events

February 13, 1975, fire

On February 13, 1975, a three-alarm fire broke out on the 11th floor of the North Tower. It spread to the 9th and 14th floors after igniting telephone cable insulation in a utility shaft that ran vertically between floors. Areas at the furthest extent of the fire were extinguished almost immediately; the original fire was put out in a few hours. Most of the damage was concentrated on the 11th floor, fueled by cabinets filled with paper, alcohol-based fluid for office machines, and other office equipment. Fireproofing protected the steel and there was no structural damage to the tower. In addition to fire damage on the 9th through the 14th floors, the water used to extinguish the fire damaged a few of the floors below. At that time, the World Trade Center had no fire sprinkler systems.[6]

February 26, 1993, bombing

The first terrorist attack on the World Trade Center occurred on February 26, 1993, at 12:17 p.m. A Ryder truck filled with 1,500 pounds (680 kg) of explosives, planted by Ramzi Yousef, detonated in the underground garage of the North Tower.[7] The blast opened a 100-foot (30 m) hole through five sublevels with the greatest damage occurring on levels B1 and B2 and significant structural damage on level B3.[126] Six people were killed, and 1,042 others were injured in the attacks, some from smoke inhalation.[127][128] Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman[129] and four other individuals[130] were later convicted for their involvement in the bombing,[129][130] while Yousef and Eyad Ismoil were convicted for carrying out the bombing.[131] According to a presiding judge, the conspirators' chief aim at the time of the attack was to destabilize the north tower and send it crashing into the south tower, toppling both landmarks.[132]

Following the bombing, floors that were blown out needed to be repaired to restore the structural support they provided to columns.[133] The slurry wall was in peril following the bombing and loss of the floor slabs that provided lateral support against pressure from Hudson River water on the other side. The refrigeration plant on sublevel B5, which provided air conditioning to the entire World Trade Center complex, was heavily damaged.[134] After the bombing, the Port Authority installed photoluminescent pathway markings in the stairwells.[135] The fire alarm system for the entire complex needed to be replaced because critical wiring and signaling in the original system were destroyed.[136] A memorial to the victims of the bombing, a reflecting pool, was installed with the names of those who were killed in the blast.[137] It was destroyed following the September 11 attacks. The names of the victims of the 1993 bombing are included in the National September 11 Memorial & Museum.[138]

January 14, 1998, robbery

In January 1998, Mafia member Ralph Guarino gained maintenance access to the World Trade Center. He arranged a three-man crew for a heist that netted over $2 million from a Brinks delivery to the 11th floor of the North Tower.[8]

Other events

On the morning of August 7, 1974, Philippe Petit performed a high-wire walk between the North and South Towers of the World Trade Center. For his unauthorized feat 1,312 feet (400 m) above the ground, he rigged a 440-pound (200 kg) cable and used a custom-made 30-foot-long (9.1 m), 55-pound (25 kg) balancing pole. He performed for 45 minutes, making eight passes along the wire.[139] Though Petit was charged with criminal trespass and disorderly conduct, he was later freed in exchange for performing for children in Central Park.[140]

On February 20, 1981, an Aerolíneas Argentinas airliner was guided away by air traffic controllers after radar signals indicated it was on a collision course with the North Tower (1 WTC). The aircraft, which was scheduled to land at nearby JFK Airport, was flying at a much lower altitude than regulations recommended.[141]

The 1995 PCA world chess championship was played on the 107th floor of the South Tower.[142]

Proposed lease

In 1998, the Port Authority approved plans to privatize the World Trade Center,[143] and in 2001 sought to lease it to a private entity. Bids for the lease came from Vornado Realty Trust, a joint bid between Brookfield Properties Corporation and Boston Properties,[144] and a joint bid by Silverstein Properties and The Westfield Group.[9] Privatizing the World Trade Center would add it to the city's tax rolls[9] and provide funds for other Port Authority projects.[145] On February 15, 2001, the Port Authority announced that Vornado Realty Trust had won the lease for the World Trade Center, paying $3.25 billion for the 99-year lease.[146] Vornado outbid Silverstein by $600 million though Silverstein upped his offer to $3.22 billion. However, Vornado insisted on last minute changes to the deal, including a shorter 39-year lease, which the Port Authority considered nonnegotiable.[147] Vornado later withdrew and Silverstein's bid for the lease to the World Trade Center was accepted on April 26, 2001,[148] and closed on July 24, 2001.[149]

Destruction

On September 11, 2001, Islamist terrorists hijacked American Airlines Flight 11 and crashed it into the northern façade of the North Tower [150] at 8:46:40 a.m.; the aircraft struck between the 93rd and 99th floors. Seventeen minutes later, at 9:03:11 a.m., a second group crashed the similarly hijacked United Airlines Flight 175 into the southern façade of the South Tower, striking it between the 77th and 85th floors.[151] The damage caused to the North Tower by Flight 11 destroyed any means of escape from above the impact zone, trapping 1,344 people.[152] Flight 175 had a much more off-centered impact compared to Flight 11, and a single stairwell was left intact; however, only a few people managed to descend successfully before the tower collapsed. Although the South Tower was struck lower than the North Tower, thus affecting more floors, a smaller number, fewer than 700, were killed instantly or trapped.[153]

At 9:59 a.m., the South Tower collapsed after burning for approximately 56 minutes. The fire caused steel structural elements, already weakened from the plane's impact, to fail. The North Tower collapsed at 10:28 a.m., after burning for approximately 102 minutes.[154] At 5:20 p.m.[155] on September 11, 2001, 7 World Trade Center began to collapse with the crumbling of the east penthouse; it collapsed completely at 5:21 p.m.[155] owing to uncontrolled fires causing structural failure.[156]

The Marriott World Trade Center hotel was destroyed during the collapse of the two towers. The three remaining buildings in the WTC plaza were extensively damaged by debris and were later demolished.[157] The cleanup and recovery process at the World Trade Center site took eight months.[158] The Deutsche Bank Building across Liberty Street from the World Trade Center complex was later condemned because of the uninhabitable toxic conditions inside; it was deconstructed, with work completed in early 2011.[159][160] The Borough of Manhattan Community College's Fiterman Hall at 30 West Broadway was also condemned owing to extensive damage, and it was demolished and completely rebuilt.[161]

In the immediate aftermath of the attacks, media reports suggested that tens of thousands might have been killed in the attacks, as over 50,000 people could have been inside the World Trade Center. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) estimated approximately 17,400 individuals were in the towers at the time of the attacks.[162] Ultimately, 2,753 death certificates (excluding those for hijackers) were filed relating to the 9/11 attacks. 2,192 civilians died in and around the World Trade Center, including employees of Cantor Fitzgerald L.P. (an investment bank on the 101st–105th floors of One World Trade Center),[163] Marsh & McLennan Companies (located immediately below Cantor Fitzgerald on floors 93–101, the location of Flight 11's impact), and Aon Corporation.[164] In addition to the civilian deaths, 414 sworn personnel were also killed: 340 New York City Fire Department (FDNY) firefighters; 71 law enforcement officers, including 37 members of the Port Authority Police Department (PAPD) and 23 members of the New York City Police Department (NYPD); 2 FDNY paramedics; and 1 FDNY chaplain. Eight EMS personnel from private agencies also died in the attacks.[165][166][167] Ten years after the attacks, the remains of only 1,629 victims had been identified.[168] Of all the people who were still in the towers when they collapsed, only 20 were pulled out alive.[169]

New World Trade Center

| Rebuilding of the World Trade Center |

|---|

| One WTC |

| 2–7 WTC |

| Other elements |

Over the following years, plans were created for the reconstruction of the World Trade Center. The Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC), established in November 2001 to oversee the rebuilding process,[170] organized competitions to select a site plan and memorial design.[171] Memory Foundations, designed by Daniel Libeskind, was selected as the master plan;[172] however, substantial changes were made to the design.[173]

The first new building at the site was 7 WTC, which opened on May 23, 2006.[174] The memorial section of the National September 11 Memorial & Museum opened on September 11, 2011,[175] and the museum opened on May 21, 2014.[176] 1 WTC opened on November 3, 2014;[177] 4 WTC opened on November 13, 2013;[178] and 3 WTC opened on June 11, 2018.[179]

In November 2013, according to an agreement made with Silverstein Properties Inc., the new 2 WTC would not be built to its full height until sufficient space was leased to make the building financially viable.[180] Above-ground construction of 5 WTC was also suspended due to a lack of tenants[181] as well as disputes between the Port Authority and the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation.[182] In mid-2015, Silverstein Properties revealed plans for a redesigned 2 WTC, to be designed by Bjarke Ingels and completed by 2020 with News Corp as anchor tenant.[183] Four years later, with no anchor tenant for 2 WTC, Silverstein expressed his intent to resume work on the tower regardless of whether a tenant had signed.[184]

Impact

On the surrounding community

The original World Trade Center created a superblock that cut through the area's street grid, isolating the complex from the rest of the community.[70][185][186] The Port Authority had demolished several streets to make way for the towers within the World Trade Center. The project involved combining the twelve-block area bounded by Vesey, Church, Liberty, and West Streets on the north, east, south, and west, respectively.[185][187] 7 World Trade Center, built on the superblock's north side in the late 1980s, was built over another block of Greenwich Street. The building acted as a physical barrier separating Tribeca to the north and the Financial District to the south.[188] The underground mall at the World Trade Center also drew shoppers away from surrounding streets.[189]

The project was seen as being monolithic and overambitious,[190] with the design having had no public input.[191] By contrast, the rebuilding plans had significant public input.[192] The public supported rebuilding a street grid through the World Trade Center site.[191][185][193] One of the rebuilding proposals included building an enclosed shopping street along the path of Cortlandt Street, one of the streets demolished to make room for the original World Trade Center.[189] However, the Port Authority ultimately decided to rebuild Cortlandt, Fulton, and Greenwich Streets, which had been destroyed during the original World Trade Center's construction.[185]

As an icon of popular culture

Before its destruction, the World Trade Center was a New York City icon, and the Twin Towers were the centerpiece that represented the entire complex. They were used in film and TV projects as "establishing shots", standing for New York City as a whole.[12] In 1999, one writer noted: "Nearly every guidebook in New York City lists the Twin Towers among the city's top ten attractions."[11]

There were several high-profile events that occurred at the World Trade Center. The most notable was held at the original WTC in 1974. French high wire acrobatic performer Philippe Petit walked between the two towers on a tightrope,[194] as shown in the documentary film Man on Wire (2008)[195] and depicted in the feature film The Walk (2015).[196] Petit walked between the towers eight times on a steel cable.[197][194] In 1975, Owen J. Quinn base-jumped from the roof of the North Tower and safely landed on the plaza between the buildings.[198] Quinn claimed that he was trying to publicize the plight of the poor.[198] In 1977, Brooklyn toymaker George Willig scaled the exterior of the South Tower. He later said, "It looked unscalable; I thought I'd like to try it."[199][200] Six years later, high-rise firefighting and rescue advocate Dan Goodwin successfully climbed the outside of the North Tower to call attention to the inability to rescue people potentially trapped in the upper floors of skyscrapers.[201][202]

The complex was featured in numerous works of popular culture; in 2006, it was estimated that the World Trade Center had appeared in some form in 472 films.[12] Several iconic meanings were attributed to the World Trade Center. Film critic David Sterritt, who lived near the complex, said that the World Trade Center's appearance in the 1978 film Superman "summarized a certain kind of American grandeur [...] the grandeur, I would say, of sheer American powerfulness". Remarking on the towers' destruction in the 1996 film Independence Day, Sterritt said, "The Twin Towers have been destroyed in various disaster movies that were made before 9/11. That became something that you couldn't do even retroactively after 9/11." Other motifs included romance, depicted in the 1988 film Working Girl, and corporate avarice, depicted in Wall Street (1987) and The Bonfire of the Vanities (1987).[203] Comic books, animated cartoons, television shows, video games, and music videos also used the complex as a setting.[204]

After the September 11 attacks

After the September 11 attacks, some movies and TV shows deleted scenes or episodes set within the World Trade Center.[205][206][207][208] For example, The Simpsons episode "The City of New York vs. Homer Simpson", which first aired in 1997, was removed from syndication after the attacks because a scene showed the World Trade Center.[209] Songs that mentioned the World Trade Center were no longer aired on radio, and the release dates of some films, such as the 2001–2002 films Sidewalks of New York, People I Know, and Spider-Man, were delayed so producers could remove scenes that included the World Trade Center.[205][204] The 2001 film Kissing Jessica Stein, which was shown at the Toronto International Film Festival the day before the attacks, had to be modified before its general public release, so the filmmakers could delete the scenes that depicted the World Trade Center.[205]

Other episodes and films mentioned the attacks directly, or depicted the World Trade Center in alternate contexts.[206] The production of some family-oriented films was also sped up due to a large demand for that genre following the attacks. Demand for horror and action films decreased, but within a short time demand returned to normal.[208] By the first anniversary of the attacks, over sixty "memorial films" had been created.[210] Filmmakers were criticized for removing scenes related to the World Trade Center. Rita Kempley of The Washington Post said "if we erase the towers from our art, we erase it [sic] from our memories".[211] Author Donald Langmead compared the phenomenon to the 1949 novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, where historic mentions of events are retroactively "rectified".[212] Other filmmakers such as Michael Bay, who directed the 1998 film Armageddon, opposed retroactively removing references to the World Trade Center based on post-9/11 attitudes.[205]

Oliver Stone's film World Trade Center—the first movie that specifically examined the effects of the attacks on the World Trade Center, as contrasted with the effects elsewhere—was released in 2006.[212] Several years after the attacks, works such as "The City of New York vs. Homer Simpson" were placed back in syndication. The National September 11 Museum has preserved many of the works that feature depictions of the original World Trade Center.[205]

See also

- List of tallest buildings in New York City

- Artwork damaged or destroyed in the September 11 attacks

- List of tallest freestanding structures in the world

- List of tallest freestanding steel structures

References

- "The city's newest hotel, the Vista International, officially opened..." UPI. July 1, 1981. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- "Twin Towers Engineered To Withstand Jet Collision". Seattle Times. February 27, 1993. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- World Trade Center at Emporis

- "History of the Twin Towers". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. June 1, 2014. Archived from the original on December 28, 2013. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2019). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved April 6, 2019. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth series.

- "Trade Center Hit by 6-Floor Fire". The New York Times. February 14, 1975. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved September 11, 2008.

- Reeve, Simon (2002). The new jackals : Ramzi Yousef, Osama Bin Laden and the future of terrorism. Boston: Northeastern University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-55553-509-4.

- Reppetto, Thomas (2007). Bringing down the mob : the war against the American Mafia. New York Godalming: Henry Holt Melia distributor. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-8050-8659-1.

- Cuozzo, Steve (January 30, 2001). "Larry Lusts for Twin Towers; Silverstein has an Eye on WTC's; Untapped Retail Potential". New York Post.

- "Man's death from World Trade Center dust brings Ground Zero toll to 2,753". NY Daily News. Associated Press. June 18, 2011. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 162.

- Langmead (2009), p. 353.

- "CNN: Pieces of ship made in 1700s found at ground zero building site". CNN. Archived from the original on January 13, 2011. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- Hartman, Amir (2004). Ruthless Execution: What Business Leaders Do When Their Companies Hit the Wall. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Financial Times Prentice Hall. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-13-101884-6.

- "Dewey Picks Board for Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times. July 6, 1946. ISSN 0362-4331.

- "Lets Port Group Disband, State Senate for Dissolution of World Trade Corporation" (PDF). The New York Times. March 11, 1949. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Gillespie (1999), pp. 32–33.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 56.

- Gillespie (1999), pp. 34–35.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 38.

- Grutzner, Charles (December 29, 1961). "Port Unit Backs Linking of H&M and Other Lines" (PDF). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Cudahy (2002), p. 56.

- Wright, George Cable (January 23, 1962). "2 States Agree on Hudson Tubes and Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 59.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 68.

- Ingraham, Joseph C. (March 29, 1965). "Port Agency Buys Downtown Tract" (PDF). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 61.

- "'Radio Row:' The neighborhood before the World Trade Center". National Public Radio. June 3, 2002. Archived from the original on October 18, 2006. Retrieved October 1, 2006.

- Smith, Terence (August 4, 1966). "City Ends Fight with Port Body on Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Smith, Terence (January 26, 1967). "Mayor Signs Pact on Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Esterow, Milton (September 21, 1962). "Architect Named for Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Huxtable, Ada Louise (January 19, 1964). "A New Era Heralded". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 49.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), p. 7.

- Pekala, Nancy (November 1, 2001). "Profile of a lost landmark; World Trade Center". Journal of Property Management.

- Huxtable, Ada Louise (May 29, 1966). "Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Buildings" (PDF). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Darton (1999), pp. 32–34.

- Grudin, Robert (April 20, 2010). Design And Truth. Yale University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-300-16203-5. Archived from the original on May 27, 2016. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- Kerr, Laurie (December 28, 2001). "Bin Laden's special complaint with the World Trade Center". Slate Magazine. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved October 12, 2015.

- Goldberger (2004), p. 25.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 75.

- Gillespie (1999), pp. 75–78.

- Ruchelman, Leonard I. (1977). The World Trade Center: Politics and Policies of Skyscraper Development. Syracuse University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-81562-180-5.

- NIST NCSTAR 1 (2005), p. 6.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), p. 1.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), pp. 40–42.

- Alfred Swenson & Pao-Chi Chang (2008). "Building construction: High-rise construction since 1945". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

The framed tube, which Khan developed for concrete structures, was applied to other tall steel buildings.

- World Trade Center Building Performance Study (2002), p. 2.33.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), p. 10.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), p. 8.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), pp. 8–9.

- "New York: A Documentary Film – The Center of the World (Construction Footage)". Port Authority / PBS. Archived from the original on March 16, 2007. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 138.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), p. 65.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), pp. 139–144.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), pp. 160–167.

- World Trade Center Building Performance Study (2002), p. 1.2.

- Iglauer, Edith (November 4, 1972). "The Biggest Foundation". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 18, 2001.

- Kapp, Martin S (July 9, 1964). "Tall Towers will Sit on Deep Foundations". Engineering News-Record.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 68.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 71.

- "New York Gets $90 Million Worth of Land for Nothing". Engineering News- Record. April 18, 1968.

- "Contracts Totaling $74,079,000 Awarded for the Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times. January 24, 1967. ISSN 0362-4331.

- "Timeline: World Trade Center chronology". PBS – American Experience. Archived from the original on May 2, 2007. Retrieved May 15, 2007.

- Carroll, Maurice (December 30, 1968). "A Section of the Hudson Tubes is Turned into Elevated Tunnel" (PDF). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Lew, H. S.; Bukowski, Richard W.; Carino, Nicholas J. (September 2005). Design, Construction, and Maintenance of Structural and Life Safety Systems (NCSTAR 1-1). National Institute of Standards and Technology. p. xxxvi.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), p. xxxvi.

- Cudahy (2002), p. 58.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 134.

- Nobel, Philip (2005). Sixteen acres : architecture and the outrageous struggle for the future of Ground Zero. New York: Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and Co. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-8050-7494-9.

- Mumford, Lewis (1974). The Pentagon of Power. The Myth of the Machine. II. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich. ISBN 978-0-15-671610-9.

- Gillespie (1999), pp. 42–44.

- Clark, Alfred E. (June 27, 1962). "Injunction Asked on Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Arnold, Martin (November 13, 1963). "High Court Plea is Lost by Foes of Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Gillespie (1999), pp. 49–50.

- Knowles, Clayton (February 14, 1964). "New Fight Begun on Trade Center". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Jaffe, Eric (September 12, 2012). "The World Trade Center's Rocky Real Estate History". The Atlantic Cities. Atlantic Media Company. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved September 11, 2012.

- "Kheel Urges Port Authority to Sell Trade Center" (PDF). The New York Times. November 12, 1969. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Steese, Edward (March 10, 1964). "Marring City's Skyline". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Whitman, Alden (March 22, 1967). "Mumford Finds City Strangled By Excess of Cars and People" (PDF). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Geist, William (February 27, 1985). "About New York: 39 years observing the observers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- Alexiou, Alice (2006). Jane Jacobs: Urban Visionary. New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-8135-3792-4.

- "List of World Trade Center tenants". cnn.com. CNN. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- Holusha, John (January 6, 2002). "Commercial Property; In Office Market, a Time of Uncertainty". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 21, 2008.

- "Ford recounts details of Sept. 11". Real Estate Weekly. BNET. February 27, 2002. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- Olshan, Jeremy (February 4, 2003). "'Not Deliverable';Mail still says 'One World Trade Center'". Newsday (New York).

- Gillespie (1999), p. 5.

- Tyson, Peter (April 30, 2002). "Twin Towers of Innovation — NOVA | PBS". www.pbs.org. Archived from the original on February 23, 2018. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- NIST NCSTAR 1 (2005), pp. 5–6.

- Taylor, R. E. (December 1966). "Computers and the Design of the World Trade Center". Journal of the Structural Division. 92 (ST–6): 75–91.

- "The World Trade Center: Statistics and History". Archived from the original on September 16, 2015. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- McDowell, Edwin (April 11, 1997). "At Trade Center Deck, Views Are Lofty, as Are the Prices". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 10, 2008. Retrieved November 21, 2008.

- "Willis Tower Building Information". Archived from the original on July 19, 2009. Retrieved December 1, 2008.

- "1973: World Trade Center Is Dynamic Duo of Height". Engineering News-Record. August 16, 1999. Archived from the original on June 11, 2002.

- "Official Opening of Iconic Burj Dubai Announced". Gulf News. November 4, 2009. Archived from the original on November 6, 2009. Retrieved November 4, 2009.

- "World's tallest building opens in Dubai". BBC News. January 4, 2010. Archived from the original on January 5, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- Eagar, Thomas W.; Musso, Christopher (2001). "Why did the world trade center collapse? Science, engineering, and speculation". JOM. Springer Nature. 53 (12): 8–11. Bibcode:2001JOM....53l...8E. doi:10.1007/s11837-001-0003-1. ISSN 1047-4838.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 123.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 214.

- "Lonnie Ostrow's Blog". Ostrow, Lonnie.

- Dunlap, David W. (December 7, 2006). "At New Trade Center, Seeking Lively (but Secure) Streets". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 15, 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- Dunlap, David W. (March 25, 2004). "Girding Against Return of the Windy City in Manhattan". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 28, 2015. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- "World Trade Center Plaza Reopens with Summer-long Performing Arts Festival". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. June 9, 1999. Archived from the original on December 28, 2008.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 2005, p. 158.

- NIST NCSTAR 1 2005, p. 58.

- Onishi, Norimitsu (February 24, 1997). "Metal Detectors, Common at Other City Landmarks, Are Not Used". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 21, 2008.

- Darton (1999), p. 152.

- Adams, Arthur (1996). The Hudson River Guidebook. New York: Fordham University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-8232-1680-2.

- Zraly, Kevin (2006). Windows on the world complete wine course. New York: Sterling Epicure. p. 260. ISBN 978-1-4549-2106-6.

- Grimes, William (September 19, 2001). "Windows That Rose So Close To the Sun". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 17, 2008. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- Zraly, Kevin (2011). Kevin Zraly's Complete Wine Course. Sterling Publishing Company, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-4027-8793-5.

- Greenhouse, Steven (June 4, 2002). "Windows on the World Workers Say Their Boss Didn't Do Enough". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- Reichl, Ruth (December 31, 1997). "Restaurants; Food That's Nearly Worthy of the View". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 22, 2018. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- Grimes, William (October 13, 2009). Appetite City: A Culinary History of New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 281. ISBN 978-1-42999-027-1.

- Sutton, Ryan (June 30, 2015). "Everything You Need to Know About Dining at One World Trade". Eater NY. Archived from the original on February 23, 2018. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 226.

- "Hotel In The Trade Center Greets Its First 100 Guests". The New York Times. April 2, 1981. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- World Trade Center Building Performance Study 2002, p. 4.1.

- Landesman, Linda Y; Weisfuse, Isaac B. (2013). Case Studies in Public Health Preparedness and Response to Disasters. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 210. ISBN 9781449645205.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 62.

- "History of the World Trade Center". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on June 7, 2015. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 114.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 217.

- Gold, Recovery of The Towers' buried treasure Archived February 25, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, NY Mag, August 27, 2011

- Rediff.com. Reuters, November 17, 2001: Buried WTC gold returns to futures trade Archived September 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved December 1, 2008.

- Lew, H.S.; Richard W. Bukowski; Nicholas J. Carino (September 2005). Design, Construction, and Maintenance of Structural and Life Safety Systems (NCSTAR 1-1). National Institute of Standards and Technology. pp. xlv.

- Mathews, Tom (March 8, 1993). "A Shaken City's Towering Inferno". Newsweek. Archived from the original on October 30, 2008. Retrieved October 26, 2008.

- Barbanel, Josh (February 27, 1993). "Tougher Code May Not Have Helped". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 20, 2008.

- Fried, Joseph P. (January 18, 1996). "Sheik Sentenced to Life in Prison in Bombing Plot". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved November 20, 2008.

- Hays, Tom & Larry Neumeister (May 25, 1994). "In Sentencing Bombers, Judge Takes Hard Line". Seattle Times / AP. Archived from the original on June 26, 2011. Retrieved November 20, 2008.

- "Jury convicts 2 in Trade Center blast". CNN. November 12, 1997. Archived from the original on September 16, 2010. Retrieved November 20, 2008.

- "Prosecutor: Yousef aimed to topple Trade Center towers". CNN. August 5, 1997. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved November 20, 2008.

- Port Authority Risk Management Staff. "The World Trade Center Complex" (PDF). United States Fire Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved May 15, 2007.

- Ramabhushanam, Ennala & Marjorie Lynch (1994). "Structural Assessment of Bomb Damage for World Trade Center". Journal of Performance of Constructed Facilities. 8 (4): 229–242. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0887-3828(1994)8:4(229).

- Amy, James D., Jr. (December 2006). "Escape from New York – The Use of Photoluminescent Pathway-marking Systems in High-Rise". Emerging Trends. Society of Fire Protection Engineers. Issue 8. Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved November 20, 2008.

- Evans, David D.; Richard D. Peacock; Erica D. Kuligowski; W. Stuart Dols; William L. Grosshandler (September 2005). Active Fire Protection Systems (NCSTAR 1–4) (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology. p. 44. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- Dwyer, Jim (February 26, 2002). "Their Monument Now Destroyed, 1993 Victims Are Remembered". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 14, 2012. Retrieved November 20, 2008.

- "Remembering the victims of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing". New York Daily News. February 13, 2018. Archived from the original on February 26, 2018. Retrieved February 25, 2018.

- Lichtenstein, Grace (August 8, 1974). "Stuntman, Eluding Guards, Walks a Tightrope Between Trade Center Towers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- "Aerialist a Hit in Central Park". The New York Times. August 30, 1974. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- Witkin, Richard (February 27, 1981). "Jet Crew to be Asked about Near Miss". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved February 19, 2018.

- Byrne, Robert (September 19, 1995). "Kasparov Gets Pressure, but No Victory". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 21, 2008.

- Herman, Eric (February 6, 2001). "PA to ease WTC tax load, rent would be cut to offset hike by city". New York Daily News.

- Bagli, Charles V. (January 31, 2001). "Bidding for Twin Towers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 20, 2008.

- Herman, Eric (January 31, 2001). "Port Authority Gets Final Bids on WTC". New York Daily News.

- "Brookfield Loses Lease Bid". Toronto Star. February 23, 2001.

- Bagli, Charles V. (March 20, 2001). "As Trade Center Talks Stumble, No. 2 Bidder Gets Another Chance". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 19, 2008. Retrieved November 20, 2008.

- Bagli, Charles V. (April 27, 2001). "Deal Is Signed To Take Over Trade Center". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 22, 2009. Retrieved November 20, 2008.

- Smothers, Ronald (July 25, 2001). "Leasing of Trade Center May Help Transit Projects, Pataki Says". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved November 20, 2008.

- Moghadam, Assaf (2008). The Globalization of Martyrdom: Al Qaeda, Salafi Jihad, and the Diffusion of Suicide Attacks. Johns Hopkins University. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-8018-9055-0.

- "The 9/11 Commission Report" (PDF). National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. July 27, 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 8, 2011. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- Dwyer, Jim; Lipton, Eric; et al. (May 26, 2002). "102 Minutes: Last Words at the Trade Center; Fighting to Live as the Towers Die". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- Lipton, Eric (July 22, 2004). "Study Maps the Location of Deaths in the Twin Towers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 28, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- NIST NCSTAR 1-1 (2005), pp. 34, 45–46.

- World Trade Center Building Performance Study (2002), pp. 5.23 to 5. 24.

- "Final Report on the Collapse of World Trade Center Building 7 – Draft for Public Comment" (PDF). NIST. August 2008. pp. xxxii. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2008.

- World Trade Center Building Performance Study (2002), pp. 3.1, 4.1

- "The Last Steel Column". The New York Times. May 30, 2002. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 30, 2013. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- World Trade Center Building Performance Study (2002), p. 6.1.

- "The Deutsche Bank Building at 130 Liberty Street". Lower Manhattan Construction Command Center. Archived from the original on August 26, 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2007.

- Shapiro, Julie (August 27, 2012). "Students Return to Rebuilt Fiterman Hall 11 Years After 9/11". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on October 27, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- Averill, Jason D.; et al. (2005). "Occupant Behavior, Egress, and Emergency Communications" (PDF). Final Reports of the Federal Building and Fire Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 14, 2009. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- "Cantor rebuilds after 9/11 losses". BBC News. London. September 4, 2006. Archived from the original on April 7, 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- Siegel, Aaron (September 11, 2007). "Industry honors fallen on 9/11 anniversary". InvestmentNews. Archived from the original on September 15, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- Grady, Denise; Revkin, Andrew C. (September 10, 2002). "Lung Ailments May Force 500 Firefighters Off Job". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- "Post-9/11 report recommends police, fire response changes". USA Today. Washington DC. Associated Press. August 19, 2002. Archived from the original on August 20, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- "Police back on day-to-day beat after 9/11 nightmare". CNN. July 21, 2002. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- Lemre, Jonathan (August 24, 2011). "Remains of WTC worker Ernest James, 40, ID'd ten years after 9/11". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on August 24, 2011. Retrieved August 25, 2011.

- Denerstein, Robert (August 4, 2006). "Terror in close-up". Rocky Mountain News. Denver, CO. Archived from the original on July 30, 2013. Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- Pérez-Peña, Richard (November 3, 2001). "A Nation Challenged; Downtown; State Plans Rebuilding Agency, Perhaps Led by Giuliani". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- McGuigan, Cathleen (November 12, 2001). "Up From The Ashes". Newsweek.

- "Refined Master Site Plan for the World Trade Center Site". Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. Archived from the original on April 16, 2014. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- Dunlap, David W. (June 12, 2012). "1 World Trade Center Is a Growing Presence, and a Changed One". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 27, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- "7 World Trade Center Opens with Musical Fanfare". Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC). May 22, 2006. Archived from the original on August 9, 2007. Retrieved July 27, 2007.

- NY1 News (September 12, 2011). "Public Gets First Glimpse Of 9/11 Memorial". Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- "National September 11 Memorial Museum opens". Fox NY. May 21, 2014. Archived from the original on May 21, 2014. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- "World Trade Center Reopens for Business". Associated Press. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "|| World Trade Center ||". Wtc.com. December 31, 2013. Archived from the original on September 9, 2008. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- "3 World Trade Center Opens Today: Here's a Look Inside". Commercial Observer. June 11, 2018. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- Levitt, David M. (November 12, 2013). "NYC's World Trade Tower Opens 40% Empty in Revival". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on February 4, 2014. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- Minchom, Clive (November 12, 2013). "New World Trade Center Coming To Life Already Impacts New York Skyline". Jewish Business News. Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- "The looming World Trade Center 'stalemate'". Downtown Express. September 11, 2014. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- "2 World Trade Center Office Space – World Trade Center". Archived from the original on October 6, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- Katz, Lily (February 11, 2019). "Silverstein May Start Building Final WTC Tower Without Signed Tenant". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on February 22, 2019. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- Dunlap, David W. (August 1, 2014). "At World Trade Center Site, Rebuilding Recreates Intersection of Long Ago". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 64.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 65.

- Sagalyn, L.B. (2016). Power at Ground Zero: Politics, Money, and the Remaking of Lower Manhattan. Oxford University Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-19-060704-3. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- Dunlap, David W. (November 24, 2005). "Does Putting Up a Glass Galleria Count as Bringing Back a Street?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- Klerks, Jan (2011). "Planning the World Trade Center 40 Years Apart". CTBUH Journal. Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (3): 29. Archived from the original on July 29, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- "WTC will be test for urbanism". CNU. September 1, 2002. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- "Ground Zero - The Stakeholders - Sacred Ground - FRONTLINE". PBS. July 4, 2004. Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- Greenspan, E. (2013). Battle for Ground Zero: Inside the Political Struggle to Rebuild the World Trade Center. St. Martin's Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-230-34138-8. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 219.

- "Wire-walk film omits 9/11 tragedy". BBC News. August 2, 2008. Archived from the original on July 21, 2018. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- McNarry, Dave (June 25, 2015). "Joseph Gordon-Levitt's 'The Walk' Running Early at Imax Locations". Variety. (Penske Media Corporation). Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- "He Had New York At His Feet". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on September 1, 2013. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- Gillespie 1999, pp. 142–143.

- Gillespie (1999), p. 149.

- Glanz & Lipton (2003), p. 218.

- "Skyscrapers". National Geographic: 169. February 1989.

- "Skyscraper Defense". Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- Poulou, Penelope (August 29, 2011). "New York's Twin Towers Appear in Many Hollywood Films". VOANews.com. Voice of America. Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- Langmead (2009), p. 354.

- Mashberg, Tom (September 10, 2019). "After Sept. 11, Twin Towers Onscreen Are a Tribute and a Painful Reminder". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- Bahr, Lindsay (January 21, 2013). "Television's uneasy relationship with the World Trade Center". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 26, 2018. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- Lemire, Christy (September 13, 2011). "Twin towers erased from some films after 9/11". Today.com. NBC News. Archived from the original on November 9, 2018. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- Dixon (2004), p. 4.

- Snierson, Dan (March 27, 2011). "'Simpsons' exec producer Al Jean: 'I completely understand' if reruns with nuclear jokes are pulled". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on July 8, 2018. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- Dixon (2004), p. 5.

- Kempley, Rita (May 10, 2002). "The unusual suspects". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- Langmead (2009), p. 355.

Bibliography

- Cudahy, Brian J. (2002), Rails Under the Mighty Hudson (2nd ed.), New York: Fordham University Press, ISBN 978-0-82890-257-1, OCLC 911046235

- Darton, Eric (1999). Divided we stand : a biography of New York's World Trade Center. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01727-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dixon, W.W. (2004). Film and Television After 9/11. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0-8093-2556-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gillespie, Angus K. (1999). Twin Towers: The Life of New York City's World Trade Center. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-2742-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Glanz, James & Lipton, Eric (2003). City in the Sky. Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-7691-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldberger, Paul (2004). Up from Zero: Politics, Architecture, and the Rebuilding of New York. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-58836-422-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Langmead, Donald (2009). Icons of American Architecture: From the Alamo to the World Trade Center. Greenwood icons. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-34207-3. Retrieved March 1, 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "World Trade Center Building Performance Study". Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 2002. Archived from the original on April 30, 2011. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- Design and Construction of Structural Systems. Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). September 2005.

- Fanella, David A.; Derecho, Arnaldo T.; Ghosh, S.K. (September 2005). Design and Construction of Structural Systems (NIST NCSTAR 1-1A) (PDF). Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

- Lew, Hai S.; Bukowski, Richard W.; Carino, Nicholas J. (September 2005). Design, Construction, and Maintenance of Structural and Life Safety Systems (NIST NCSTAR 1-1) (PDF). Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

- Gross, John L.; McAllister, Therese P. (September 2005). Structural Fire Response and Probable Collapse Sequence of the World Trade Center Towers (NIST NCSTAR 1–6) (PDF). Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

- Sivaraj Shyam-Sunder; Richard G. Gann; William L. Grosshandler; Hai S. Lew; Richard W. Bukowski; Fahim Sadek; Frank W. Gayle; John L. Gross; Therese P. McAllister (September 2005). Final Report of the National Construction Safety Team on the Collapses of the World Trade Center Tower (NIST NCSTAR 1) (PDF). Federal Building and Fire Safety Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to World Trade Center (1970–2001). |

- World Trade Center – Silverstein Properties

- World Trade Center (1997) - World Trade Center (2001) – Port Authority of New York & New Jersey

- World Trade Center at Curlie

- Building the Twin Towers: A Tribute – slideshow by Life magazine

- New York: A Documentary film features the construction and destruction of the World Trade Center in the seventh and final episode of the series directed by Ric Burns.

- Historic video with scenes of World Trade Center under construction in 1970

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. NY-6369, "World Trade Center Site", 103 photos, 21 data pages, 8 photo caption pages

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Empire State Building |

Tallest building in the world 1970–1974 (North Tower) |

Succeeded by Willis Tower |

| Tallest building in the United States 1970–1974 (North Tower) | ||

| Tallest building with the most floors 1970–2001 | ||

| Tallest building in New York City 1970–2001 (North Tower) |

Succeeded by Empire State Building | |

| Tallest building with the most floors ever 1970–2008 |

Succeeded by Burj Khalifa | |

| Preceded by City National Plaza |

Tallest twin towers in the world 1970–1998 |

Succeeded by Petronas Towers |