State room

A state room in a large European mansion is usually one of a suite of very grand rooms which were designed to impress. The term was most widely used in the 17th and 18th centuries. They were the most lavishly decorated in the house and contained the finest works of art. State rooms were usually only found in the houses of the upper echelons of the aristocracy, those who were likely to entertain a head of state. They were generally to accommodate and entertain distinguished guests, especially a monarch and/or a royal consort, or other high-ranking aristocrats and state officials, hence the name. In their original form a set of state rooms made up a state apartment, which always included a bedroom.

United Kingdom

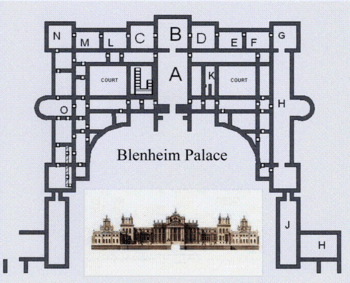

In the United Kingdom in particular, state rooms in country houses were seldom used. The owner of the house and his family actually lived in the "second best" apartments in the house. There was usually an odd number of state rooms for the following reason: at the centre of the facade, the largest and most lavish room, (for example at Wilton House the famed Double Cube Room), or as at Blenheim Palace (right) this was a gathering place for the court of the honoured guest. Leading symmetrically from the centre room on either side were often one or two suites of smaller, but still very grand state rooms, often in enfilade, for the sole use of the occupant of the final room at each end of the facade – the state bedroom. Unlike the main reception rooms of later houses, state apartments were not freely open to all the guests in the house. Admittance to the state apartment was a privilege, and the further one penetrated (there were many variations, but an apartment might include for example an anteroom; withdrawing room; bedroom; dressing room; and closet) the greater the honour.

Changes from the early 18th century

From the early 18th century, as aristocratic lifestyles slowly became less formal, there was a move on the one hand to increase the number of shared living rooms in a large house and to give them more specialised functions (music rooms and billiard rooms for example) and on the other hand to make bedroom suites more private. In houses from earlier than around 1720 which survived without major structural alteration, the state rooms sometimes became a meaningless succession of drawing rooms and the original intention was lost. This is certainly true at Wilton House, Blenheim Palace, and Castle Howard. On the other hand, there were a few houses, and royal palaces, most of them exceptionally large, which were laid out in such a way that the state rooms could be left in their original form, while other rooms were converted to meet the new needs of the 18th and 19th centuries, or where funds were available to simply add on extra wings to meet the new requirements. Examples of such residences with surviving state suites which have never really changed their function include Chatsworth House and Boughton House.

The term "state" continued to be used in the names of individual rooms in some post 1720 houses (e.g. state dining room; state bedroom), but by then the original concept of a self-contained state apartment for an honoured personage was lost, and the term "state" can be taken more accurately to mean "best".

On board a ship

On board a ship, the term state room defines a superior first-class cabin.

References

- Girouard, Mark (1978). Life in the English Country House. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02273-5.

- Halliday, F. E. (1967). Cultural History of England. London: Thames and Hudson.

- The Country House in Perspective. Pavilion Books Ltd. ISBN 0-8021-1228-5.