Roof

A roof is the top covering of a building, including all materials and constructions necessary to support it on the walls of the building or on uprights, providing protection against rain, snow, sunlight, extremes of temperature, and wind.[1] A roof is part of the building envelope.

The characteristics of a roof are dependent upon the purpose of the building that it covers, the available roofing materials and the local traditions of construction and wider concepts of architectural design and practice and may also be governed by local or national legislation. In most countries a roof protects primarily against rain. A verandah may be roofed with material that protects against sunlight but admits the other elements. The roof of a garden conservatory protects plants from cold, wind, and rain, but admits light.

A roof may also provide additional living space, for example a roof garden.

Etymology

Old English hrof "roof, ceiling, top, summit; heaven, sky," also figuratively, "highest point of something," from Proto-Germanic *khrofam (cf. Dutch roef "deckhouse, cabin, coffin-lid," Middle High German rof "penthouse," Old Norse hrof "boat shed").

There are no apparent connections outside the Germanic family. "English alone has retained the word in a general sense, for which the other languages use forms corresponding to OE. þæc thatch" [OED].

Design elements

The elements in the design of a roof are:

- the material

- the construction

- the durability

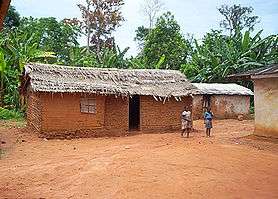

The material of a roof may range from banana leaves, wheaten straw or seagrass to laminated glass, copper (see: copper roofing), aluminium sheeting and pre-cast concrete. In many parts of the world ceramic tiles have been the predominant roofing material for centuries, if not millennia. Other roofing materials include asphalt, coal tar pitch, EPDM rubber, Hypalon, polyurethane foam, PVC, slate, Teflon fabric, TPO, and wood shakes and shingles.

The construction of a roof is determined by its method of support and how the underneath space is bridged and whether or not the roof is pitched. The pitch is the angle at which the roof rises from its lowest to highest point. Most US domestic architecture, except in very dry regions, has roofs that are sloped, or pitched. Although modern construction elements such as drainpipes may remove the need for pitch, roofs are pitched for reasons of tradition and aesthetics. So the pitch is partly dependent upon stylistic factors, and partially to do with practicalities.

Some types of roofing, for example thatch, require a steep pitch in order to be waterproof and durable. Other types of roofing, for example pantiles, are unstable on a steeply pitched roof but provide excellent weather protection at a relatively low angle. In regions where there is little rain, an almost flat roof with a slight run-off provides adequate protection against an occasional downpour. Drainpipes also remove the need for a sloping roof.

A person that specializes in roof construction is called a roofer.

The durability of a roof is a matter of concern because the roof is often the least accessible part of a building for purposes of repair and renewal, while its damage or destruction can have serious effects.

Form

The shape of roofs differs greatly from region to region. The main factors which influence the shape of roofs are the climate and the materials available for roof structure and the outer covering.[2]

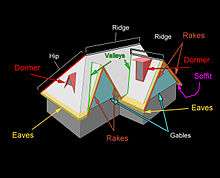

The basic shapes of roofs are flat, mono-pitched, gabled, hipped, butterfly, arched and domed. There are many variations on these types. Roofs constructed of flat sections that are sloped are referred to as pitched roofs (generally if the angle exceeds 10 degrees).[3] Pitched roofs, including gabled, hipped and skillion roofs, make up the greatest number of domestic roofs. Some roofs follow organic shapes, either by architectural design or because a flexible material such as thatch has been used in the construction.

Parts

There are two parts to a roof: its supporting structure and its outer skin, or uppermost weatherproof layer. In a minority of buildings, the outer layer is also a self-supporting structure.

The roof structure is generally supported upon walls, although some building styles, for example, geodesic and A-frame, blur the distinction between wall and roof.

Support

The supporting structure of a roof usually comprises beams that are long and of strong, fairly rigid material such as timber, and since the mid-19th century, cast iron or steel. In countries that use bamboo extensively, the flexibility of the material causes a distinctive curving line to the roof, characteristic of Oriental architecture.

Timber lends itself to a great variety of roof shapes. The timber structure can fulfil an aesthetic as well as practical function, when left exposed to view.

Stone lintels have been used to support roofs since prehistoric times, but cannot bridge large distances. The stone arch came into extensive use in the ancient Roman period and in variant forms could be used to span spaces up to 140 feet (43 m) across. The stone arch or vault, with or without ribs, dominated the roof structures of major architectural works for about 2,000 years, only giving way to iron beams with the Industrial Revolution and the designing of such buildings as Paxton's Crystal Palace, completed 1851.

With continual improvements in steel girders, these became the major structural support for large roofs, and eventually for ordinary houses as well. Another form of girder is the reinforced concrete beam, in which metal rods are encased in concrete, giving it greater strength under tension.

Outer layer

This part of the roof shows great variation dependent upon availability of material. In vernacular architecture, roofing material is often vegetation, such as thatches, the most durable being sea grass with a life of perhaps 40 years. In many Asian countries bamboo is used both for the supporting structure and the outer layer where split bamboo stems are laid turned alternately and overlapped. In areas with an abundance of timber, wooden shingles and boards are used, while in some countries the bark of certain trees can be peeled off in thick, heavy sheets and used for roofing.

The 20th century saw the manufacture of composition asphalt shingles which can last from a thin 20-year shingle to the thickest which are limited lifetime shingles, the cost depending on the thickness and durability of the shingle. When a layer of shingles wears out, they are usually stripped, along with the underlay and roofing nails, allowing a new layer to be installed. An alternative method is to install another layer directly over the worn layer. While this method is faster, it does not allow the roof sheathing to be inspected and water damage, often associated with worn shingles, to be repaired. Having multiple layers of old shingles under a new layer causes roofing nails to be located further from the sheathing, weakening their hold. The greatest concern with this method is that the weight of the extra material could exceed the dead load capacity of the roof structure and cause collapse. Because of this, jurisdictions which use the International Building Code prohibit the installation of new roofing on top of an existing roof that has two or more applications of any type of roof covering; the existing roofing material must be removed before installing a new roof.[4]

Slate is an ideal, and durable material, while in the Swiss Alps roofs are made from huge slabs of stone, several inches thick. The slate roof is often considered the best type of roofing. A slate roof may last 75 to 150 years, and even longer. However, slate roofs are often expensive to install – in the US, for example, a slate roof may have the same cost as the rest of the house. Often, the first part of a slate roof to fail is the fixing nails; they corrode, allowing the slates to slip. In the UK, this condition is known as "nail sickness". Because of this problem, fixing nails made of stainless steel or copper are recommended, and even these must be protected from the weather.[5]

Asbestos, usually in bonded corrugated panels, has been used widely in the 20th century as an inexpensive, non-flammable roofing material with excellent insulating properties. Health and legal issues involved in the mining and handling of asbestos products means that it is no longer used as a new roofing material. However, many asbestos roofs continue to exist, particularly in South America and Asia.

Roofs made of cut turf (modern ones known as green roofs, traditional ones as sod roofs) have good insulating properties and are increasingly encouraged as a way of "greening" the Earth. Adobe roofs are roofs of clay, mixed with binding material such as straw or animal hair, and plastered on lathes to form a flat or gently sloped roof, usually in areas of low rainfall.

In areas where clay is plentiful, roofs of baked tiles have been the major form of roofing. The casting and firing of roof tiles is an industry that is often associated with brickworks. While the shape and colour of tiles was once regionally distinctive, now tiles of many shapes and colours are produced commercially, to suit the taste and pocketbook of the purchaser.

Sheet metal in the form of copper and lead has also been used for many hundreds of years. Both are expensive but durable, the vast copper roof of Chartres Cathedral, oxidised to a pale green colour, having been in place for hundreds of years. Lead, which is sometimes used for church roofs, was most commonly used as flashing in valleys and around chimneys on domestic roofs, particularly those of slate. Copper was used for the same purpose.

In the 19th century, iron, electroplated with zinc to improve its resistance to rust, became a light-weight, easily transported, waterproofing material. Its low cost and easy application made it the most accessible commercial roofing, worldwide. Since then, many types of metal roofing have been developed. Steel shingle or standing-seam roofs last about 50 years or more depending on both the method of installation and the moisture barrier (underlayment) used and are between the cost of shingle roofs and slate roofs. In the 20th century a large number of roofing materials were developed, including roofs based on bitumen (already used in previous centuries), on rubber and on a range of synthetics such as thermoplastic and on fibreglass.

Functions

Insulation

Because the purpose of a roof is to secure people and their possessions from climatic elements, the insulating properties of a roof are a consideration in its structure and the choice of roofing material.

Some roofing materials, particularly those of natural fibrous material, such as thatch, have excellent insulating properties. For those that do not, extra insulation is often installed under the outer layer. In developed countries, the majority of dwellings have a ceiling installed under the structural members of the roof. The purpose of a ceiling is to insulate against heat and cold, noise, dirt and often from the droppings and lice of birds who frequently choose roofs as nesting places.

Concrete tiles can be used as insulation. When installed leaving a space between the tiles and the roof surface, it can reduce heating caused by the sun.

Forms of insulation are felt or plastic sheeting, sometimes with a reflective surface, installed directly below the tiles or other material; synthetic foam batting laid above the ceiling and recycled paper products and other such materials that can be inserted or sprayed into roof cavities. So called Cool roofs are becoming increasingly popular, and in some cases are mandated by local codes. Cool roofs are defined as roofs with both high reflectivity and high thermal emittance.

Poorly insulated and ventilated roofing can suffer from problems such as the formation of ice dams around the overhanging eaves in cold weather, causing water from melted snow on upper parts of the roof to penetrate the roofing material. Ice dams occur when heat escapes through the uppermost part of the roof, and the snow at those points melts, refreezing as it drips along the shingles, and collecting in the form of ice at the lower points. This can result in structural damage from stress, including the destruction of gutter and drainage systems.

Drainage

The primary job of most roofs is to keep out water. The large area of a roof repels a lot of water, which must be directed in some suitable way, so that it does not cause damage or inconvenience.

Flat roof of adobe dwellings generally have a very slight slope. In a Middle Eastern country, where the roof may be used for recreation, it is often walled, and drainage holes must be provided to stop water from pooling and seeping through the porous roofing material.

Similar problems, although on a very much larger scale, confront the builders of modern commercial properties which often have flat roofs. Because of the very large nature of such roofs, it is essential that the outer skin be of a highly impermeable material. Most industrial and commercial structures have conventional roofs of low pitch.

In general, the pitch of the roof is proportional to the amount of precipitation. Houses in areas of low rainfall frequently have roofs of low pitch while those in areas of high rainfall and snow, have steep roofs. The longhouses of Papua New Guinea, for example, being roof-dominated architecture, the high roofs sweeping almost to the ground. The high steeply-pitched roofs of Germany and Holland are typical in regions of snowfall. In parts of North America such as Buffalo, USA or Montreal, Canada, there is a required minimum slope of 6 inches in 12 inches, a pitch of 30 degrees.

There are regional building styles which contradict this trend, the stone roofs of the Alpine chalets being usually of gentler incline. These buildings tend to accumulate a large amount of snow on them, which is seen as a factor in their insulation. The pitch of the roof is in part determined by the roofing material available, a pitch of 3/12 or greater slope generally being covered with asphalt shingles, wood shake, corrugated steel, slate or tile.

The water repelled by the roof during a rainstorm is potentially damaging to the building that the roof protects. If it runs down the walls, it may seep into the mortar or through panels. If it lies around the foundations it may cause seepage to the interior, rising damp or dry rot. For this reason most buildings have a system in place to protect the walls of a building from most of the roof water. Overhanging eaves are commonly employed for this purpose. Most modern roofs and many old ones have systems of valleys, gutters, waterspouts, waterheads and drainpipes to remove the water from the vicinity of the building. In many parts of the world, roofwater is collected and stored for domestic use.

Areas prone to heavy snow benefit from a metal roof because their smooth surfaces shed the weight of snow more easily and resist the force of wind better than a wood shingle or a concrete tile roof.

- Insulation, drainage and solar roofing

- The flat roofs of the Middle East, Israel

Steeply pitched, gabled roofs in Northern Europe

Steeply pitched, gabled roofs in Northern Europe The overhanging eaves of China

The overhanging eaves of China

Solar roofs

Newer systems include solar shingles which generate electricity as well as cover the roof. There are also solar systems available that generate hot water or hot air and which can also act as a roof covering. More complex systems may carry out all of these functions: generate electricity, recover thermal energy, and also act as a roof covering.

Solar systems can be integrated with roofs by:

- integration in the covering of pitched roofs, e.g. solar shingles.

- mounting on an existing roof, e.g. solar panel on a tile roof.

- integration in a flat roof membrane using heat welding, e.g. PVC.

- mounting on a flat roof with a construction and additional weight to prevent uplift from wind.

Gallery of roof shapes

- Roof shapes

Pitched roof with decorated gable, Chang Mai, Thailand

Pitched roof with decorated gable, Chang Mai, Thailand Sateri roof (with vertical break in pitch), Sweden

Sateri roof (with vertical break in pitch), Sweden Mansard roof, county jail, Mount Gilead, Ohio

Mansard roof, county jail, Mount Gilead, Ohio

- Flat roofs, Haikou City, Hainan, China

Sloped flat roof, house, Western Australia

Sloped flat roof, house, Western Australia Butterfly roof in Paradise Palms in the southwestern United States

Butterfly roof in Paradise Palms in the southwestern United States

Gallery of significant roofs

The polychrome tiles of the Hospices de Beaune, France.

The polychrome tiles of the Hospices de Beaune, France. The glazed ceramic tiles of the Sydney Opera House.

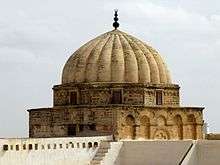

The glazed ceramic tiles of the Sydney Opera House. Ashlar masonry dome of the Great Mosque of Kairoun, Tunisia

Ashlar masonry dome of the Great Mosque of Kairoun, Tunisia Imbrex and tegula tiles on the dome of Florence Cathedral.

Imbrex and tegula tiles on the dome of Florence Cathedral. The marble dome of the Taj Mahal.

The marble dome of the Taj Mahal. The copper roof of Speyer Cathedral, Germany.

The copper roof of Speyer Cathedral, Germany. The lead roof of King's College Chapel, England.

The lead roof of King's College Chapel, England. The glass roof of the Grand Palais, Paris.

The glass roof of the Grand Palais, Paris.

See also

- List of roof shapes

- Domestic roof construction

- Roof cleaning

- Tensile architecture

- Thin-shell structure

- List of Greco-Roman roofs

References

- Harris, Cyril M. (editor). Dictionary of Architecture and Construction, Third Edition, New York, McGraw Hill, 2000, p. 775

- "Roofing Materials to Protect You From the Elements". HuffPost. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- C.M.Harris,Dictionary of Architecture & Construction

- "Chapter 9 - Roof Assemblies". publicecodes.cyberregs.com. Archived from the original on 2015-09-03. Retrieved 2015-08-31.

- "TRADITIONAL ROOFING MAGAZINE - Six Steps to Building a 150 Year Roof by Joseph Jenkins". www.traditionalroofing.com. Retrieved 2015-09-01.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roofs. |

.jpg)