Foundation (engineering)

In engineering, a foundation is the element of a structure which connects it to the ground, and transfers loads from the structure to the ground. Foundations are generally considered either shallow or deep.[1] Foundation engineering is the application of soil mechanics and rock mechanics (Geotechnical engineering) in the design of foundation elements of structures.

Purpose

Foundations provide the structure's stability from the ground:

- To distribute the weight of the structure over a large area in order to avoid overloading the underlying soil (possibly causing unequal settlement).

- To anchor the structure against natural forces including earthquakes, floods, frost heaves, tornadoes and wind.

- To provide a level surface for construction.

- To anchor the structure deeply into the ground, increasing its stability and preventing overloading.

- To prevent lateral movements of the supported structure (in some cases).

Requirements of a good foundation

The design and the construction of a well-performing foundation must possess some basic requirements that must not be ignored. They are:

- The design and the construction of the foundation is done such that it can sustain as well as transmit the dead and the imposed loads to the soil. This transfer has to be carried out without resulting in any form of settlement that can result in any form of stability issues for the structure.

- Differential settlements can be avoided by having a rigid base for the foundation. These issues are more pronounced in areas where the superimposed loads are not uniform in nature.

- Based on the soil and area it is recommended to have a deeper foundation so that it can guard any form of damage or distress. These are mainly caused due to the problem of shrinkage and swelling because of temperature changes.

- The location of the foundation chosen must be an area that is not affected or influenced by future works or factors.

Historic foundation types

.jpg)

Earthfast or post in ground construction

Buildings and structures have a long history of being built with wood in contact with the ground.[2][3] Post in ground construction may technically have no foundation. Timber pilings were used on soft or wet ground even below stone or masonry walls.[4] In marine construction and bridge building a crisscross of timbers or steel beams in concrete is called grillage.[5]

Padstones

Perhaps the simplest foundation is the padstone, a single stone which both spreads the weight on the ground and raises the timber off the ground.[6] Staddle stones are a specific type of padstones.

Stone foundations

Dry stone and stones laid in mortar to build foundations are common in many parts of the world. Dry laid stone foundations may have been painted with mortar after construction. Sometimes the top, visible course of stone is hewn, quarried stones.[7] Besides using mortar, stones can also be put in a gabion.[8] One disadvantage is that if using regular steel rebars, the gabion would last much less long than when using mortar (due to rusting). Using weathering steel rebars could reduce this disadvantage somewhat.

Rubble trench foundations

Rubble trench foundations are a shallow trench filled with rubble or stones. These foundations extend below the frost line and may have a drain pipe which helps groundwater drain away. They are suitable for soils with a capacity of more than 10 tonnes/m2 (2,000 pounds per square foot).

Gallery of shallow foundation types

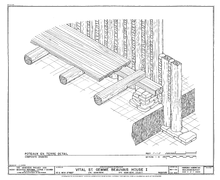

Drawing of Poteaux-en-Terre post in ground type of wall construction (this example technically called pallisade construction) in the Beauvais House in Ste Genevieve, Missouri, U.S.A.

Drawing of Poteaux-en-Terre post in ground type of wall construction (this example technically called pallisade construction) in the Beauvais House in Ste Genevieve, Missouri, U.S.A. PSM V24 D321 A primitive stilt house in Switzerland on wood pilings.

PSM V24 D321 A primitive stilt house in Switzerland on wood pilings. A granary on staddle stones, a type of padstone

A granary on staddle stones, a type of padstone Black Eagle Dam - cross-section of construction plans for 1892 structure

Black Eagle Dam - cross-section of construction plans for 1892 structure Davis House dry-laid stone foundation ruin, Gardiner, NY

Davis House dry-laid stone foundation ruin, Gardiner, NY A basic type of rubble trench foundation

A basic type of rubble trench foundation- Typical residential poured concrete foundation, except for the lack of anchor bolts. The concrete walls are supported on continuous footings. There is also a concrete slab floor. Note the standing water in the perimeter French drain trenches.

Modern foundation types

Shallow foundations

Shallow foundations, often called footings, are usually embedded about a metre or so into soil. One common type is the spread footing which consists of strips or pads of concrete (or other materials) which extend below the frost line and transfer the weight from walls and columns to the soil or bedrock.

Another common type of shallow foundation is the slab-on-grade foundation where the weight of the structure is transferred to the soil through a concrete slab placed at the surface. Slab-on-grade foundations can be reinforced mat slabs, which range from 25 cm to several meters thick, depending on the size of the building, or post-tensioned slabs, which are typically at least 20 cm for houses, and thicker for heavier structures.

Deep foundations

A deep foundation is used to transfer the load of a structure down through the upper weak layer of topsoil to the stronger layer of subsoil below. There are different types of deep footings including impact driven piles, drilled shafts, caissons, helical piles, geo-piers and earth stabilized columns. The naming conventions for different types of footings vary between different engineers. Historically, piles were wood, later steel, reinforced concrete, and pre-tensioned concrete.

Monopile foundation

A monopile foundation is a type of deep foundation which uses a single, generally large-diameter, structural element embedded into the earth to support all the loads (weight, wind, etc.) of a large above-surface structure.

Many monopile foundations[9] have been utilized in recent years for economically constructing fixed-bottom offshore wind farms in shallow-water subsea locations.[10] For example, a single wind farm off the coast of England went online in 2008 with over 100 turbines, each mounted on a 4.74-meter-diameter monopile footing in ocean depths up to 16 metres of water.[11]

Design

Foundations are designed to have an adequate load capacity depending on the type of subsoil/rock supporting the foundation by a geotechnical engineer, and the footing itself may be designed structurally by a structural engineer. The primary design concerns are settlement and bearing capacity. When considering settlement, total settlement and differential settlement is normally considered. Differential settlement is when one part of a foundation settles more than another part. This can cause problems to the structure which the foundation is supporting. Expansive clay soils can also cause problems.

See also

- Underpinning

- Structural settlement

References

- Terzaghi, Karl; Peck, Ralph Brazelton; Mesri, Gholamreza (1996), Soil mechanics in engineering practice (3rd ed.), New York: John Wiley & Sons, p. 386, ISBN 0-471-08658-4

- Crabtree, Pam J.. Medieval archaeology: an encyclopedia. New York: Garland Pub., 2001. 113.

- Edwards, Jay Dearborn, and Nicolas Verton. A Creole lexicon architecture, landscape, people. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2004. 92.

- Nicholson, Peter. Practical Masonry, Bricklaying and Plastering, Both Plain and Ornamental. Thomas Kelly: London. 1838. 30–31.

- Beohar, Rakesh Ranjan. Basic Civil Engineering. 2005. 90. ISBN 8170087937

- Darvill, Timothy. The concise Oxford dictionary of archaeology. 6th ed. [i.e. 2nd ed. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2008. Padstone. ISBN 0199534047

- Garvin, James L.. A building history of northern New England. Hanover: University Press of New England, 2001. 10. Print.

- Stones in gabion for foundation, done in Diez Casas Para Diez Familias (10x10)'s Casa Rosenda; see Design Like You Give a Damn 2 book by Kate Stohr

- Offshore Wind Turbine Foundations Archived 2010-02-28 at the Wayback Machine, 2009-09-09, accessed 2010-04-12.

- Constructing a turbine foundation Archived 2011-05-21 at the Wayback Machine Horns Rev project, Elsam monopile foundation construction process, accessed 2010-04-12

- "Lynn & Inner Dowsing Offshore Wind Farms". MT Højgaard. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Foundations. |