Rhine Province

The Rhine Province (German: Rheinprovinz), also known as Rhenish Prussia (Rheinpreußen) or synonymous with the Rhineland (Rheinland), was the westernmost province of the Kingdom of Prussia and the Free State of Prussia, within the German Reich, from 1822 to 1946. It was created from the provinces of the Lower Rhine and Jülich-Cleves-Berg. Its capital was Koblenz and in 1939 it had 8 million inhabitants. The Province of Hohenzollern was militarily associated with the Oberpräsident of the Rhine Province.

| Rhine Province Rheinprovinz | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province of Prussia | |||||||||||||||||

| 1822–1946 | |||||||||||||||||

Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||||||||

.svg.png) The Rhine Province (red), within the Kingdom of Prussia, within the German Empire | |||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Koblenz | ||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||

| • Coordinates | 50°22′N 7°36′E | ||||||||||||||||

• 1939 | 24,477 km2 (9,451 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||

• 1905 | 6,435,778 | ||||||||||||||||

• 1939 | 7,931,942 | ||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

• Established | 1822 | ||||||||||||||||

• Loss of Saar | 1920 | ||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1946 | ||||||||||||||||

| Political subdivisions | Aachen Cologne Düsseldorf Koblenz Trier | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of |

| ||||||||||||||||

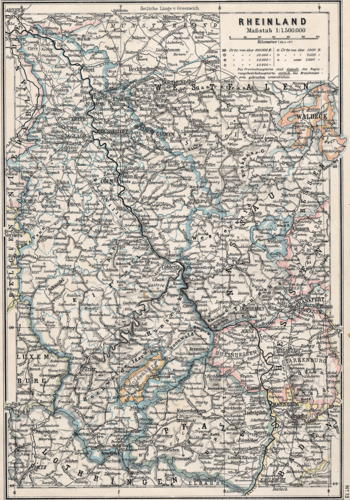

The Rhine Province was bounded on the north by the Netherlands, on the east by the Prussian provinces of Westphalia and Hesse-Nassau, and the grand duchy of Hesse-Darmstadt, on the southeast by the Palatinate (a district of the Kingdom of Bavaria), on the south and southwest by Lorraine, and on the west by Luxembourg, Belgium and the Netherlands.

The small exclave district of Wetzlar, wedged between the grand duchy states Hesse-Nassau and Hesse-Darmstadt was also part of the Rhine Province. The principality of Birkenfeld, on the other hand, was an enclave of the Grand Duchy of Oldenburg, a separate state of the German Empire.

In 1911, the extent of the province was 10,423 km2 (4,024 sq mi); its extreme length, from north to south, was nearly 200 km (120 mi), and its greatest breadth was just under 90 km (56 mi). It included about 200 km (120 mi) of the course of the Rhine, which formed the eastern border of the province from Bingen to Koblenz, and then flows in a north-northwesterly direction inside the province, approximately following its eastern border.[1]

Demographics

The population of the Rhine Province in 1905 was 6,435,778, including 4,472,058 Roman Catholics, 1,877,582 Protestants and 55,408 Jews. The left bank was predominantly Catholic, while on the right bank about half the population was Protestant. The great bulk of the population was ethnically German, although some villages and towns in the northern part (Province of Jülich-Cleves-Berg) were more oriented toward the Netherlands. On the western and southern frontiers (especially in the Saarland) resided smaller French-speaking communities, while the industrial region of the Ruhr housed recent Polish migrants from the eastern provinces of the Empire.

The Rhine Province was the most densely populated part of Prussia, the general average being 617 persons per km2. The province contains a greater number of large towns than any other province in Prussia. Upwards of half, the population were supported by industrial and commercial pursuits, and barely a quarter by agriculture. There was the University of Bonn, and elementary education was especially successful.[2]

Government

For purposes of administration the province was divided into the five districts (Regierungsbezirke) of Koblenz, Düsseldorf, Cologne, Aachen and Trier. Koblenz was the official capital, though Cologne was the largest and most important city. Being a frontier province, the Rhineland was strongly garrisoned, and the Rhine was guarded by the three strong fortresses of Cologne with Deutz, Koblenz with Ehrenbreitstein, and Wesel. The province sent 35 members to the German Reichstag and 62 to the Prussian House of Representatives.[2]

Economy

Agriculture

Of the total area of the Rhine Province about 45% was occupied by arable land, 16% by meadows and pastures, and 31% by forests. Little except oats and potatoes could be raised on the high-lying plateaus in the south of the province, but the river-valleys and the northern lowlands were extremely fertile. The great bulk of the soil was in the hands of small proprietors, and this is alleged to have had the effect of somewhat retarding the progress of scientific agriculture. The usual cereal crops were, however, all grown with success, and tobacco, hops, flax, hemp and beetroot (for sugar) were cultivated for commercial purposes. Large quantities of fruit were also produced.[1]

The vine-culture occupied a space of about 30,000 acres (120 km2), about half of which was in the valley of the Mosel, a third in that of the Rhine itself, and the rest mainly on the Nahe and the Ahr. In the hilly districts more than half the surface was sometimes occupied by forests, and large plantations of oak are formed for the use of the bark in tanning.[1]

Considerable herds of cattle were reared on the rich pastures of the lower Rhine, but the number of sheep in the province was comparatively small, not greatly in excess of that of the goats. The wooded hills were well stocked with deer, and a stray wolf occasionally found its way from the forests of the Ardennes into those of the Hunsrück.[3]

The salmon fishery of the Rhine was very productive, and trout abound in the mountain streams.[2]

Mineral resources

The great mineral wealth of the Rhine Province furnished its most substantial claim to the title of the "richest jewel in the crown of Prussia".[2]

Besides parts of the carboniferous measures of the Saar and the Ruhr, it also contains important deposits of coal near Aachen. Iron ore was found in abundance near Koblenz, the Bleiberg in the Eifel possessed an apparently inexhaustible supply of lead, and zinc was found near Cologne and Aachen. The mineral products of the district also included lignite, copper, manganese, vitriol, lime, gypsum, volcanic stones (used for millstones) and slates. By far the most important item was coal.[2]

Of the numerous mineral springs, the best known were those of Aachen and Kreuznach.[2]

Industries

The mineral resources of the Rhine Province, coupled with its favourable situation and the facilities of transit afforded by its great waterway, made it the most important manufacturing district in Germany.[2]

The industry was mainly concentrated around two chief centres, Aachen and Düsseldorf (with the valley of the Wupper), while there were naturally few manufacturers in the hilly districts of the south or the marshy flats of the north. The largest iron and steel works were at Essen, Oberhausen, Duisburg, Düsseldorf and Cologne, while cutlery and other small metallic wares were extensively made at Solingen, Remscheid and Aachen.[2]

The cloth of Aachen and the silk of Krefeld formed important articles of export. The chief industries of Elberfeld-Barmen and the valley of the Wupper was cotton-weaving, calico-printing and the manufacture of turkey red and other dyes. Linen was largely made at Mönchengladbach, leather at Malmedy, glass in the Saar district and beetroot sugar near Cologne.[2]

Though the Rhineland was par excellence the country of the vine, beer was produced in quantities, distilleries were also numerous, and large quantities of sparkling Mosel wine were made at Koblenz, chiefly for exportation to Britain.[2]

Commerce was greatly aided by the navigable rivers, a very extensive network of railways, and the excellent roads constructed during the French régime. The imports consist mainly of raw material for working up in the factories of the district, while the principal exports are coal, fruit, wine, dyes, cloth, silk and other manufactured articles of various descriptions.[2]

History

In the 1815 Congress of Vienna,[4] Prussia gained control of the duchies of Cleves, Berg, Gelderland and Jülich, the ecclesiastical principalities of Trier and Cologne, the free cities of Aachen and Cologne, and nearly one hundred small lordships and abbeys which would all be amalgamated into the new Prussian Rhine Province.[2] In 1822 Prussia established the Rhine Province by joining the provinces of Lower Rhine and Jülich-Cleves-Berg. Its capital was Koblenz; it had 8.0 million inhabitants by 1939. In 1920, the Saar was separated from the Rhine Province and administered by the League of Nations until a plebiscite in 1935, when the region was returned to Germany. At the same time, in 1920, the districts of Eupen and Malmedy were transferred to Belgium (see German-Speaking Community of Belgium). In 1946, the Rhine Province was divided up between the newly founded states of North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate. The town of Wetzlar became part of Hesse.

Following World War I

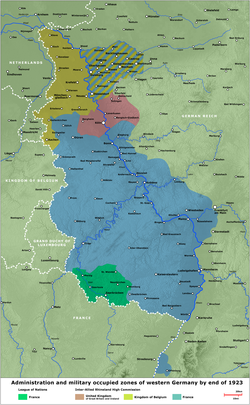

Following the Armistice of 1918, Allied forces occupied the Rhineland as far east as the river with some small bridgeheads on the east bank at places like Cologne. Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles of 1919 the occupation was continued and the Inter-Allied Rhineland High Commission was set up to supervise affairs. The treaty specified three occupation zones, which were due to be evacuated by Allied troops five, ten and finally 15 years after the formal ratification of the treaty, which took place in 1920, thus the occupation was intended to last until 1935. In fact, the last Allied troops left Germany five years prior to that date in 1930 in a good-will reaction to the Weimar Republic's policy of reconciliation in the era of Gustav Stresemann and the Locarno Pact.

Sections of the Rhineland, that had once belonged to the Habsburg Netherlands' Duchy of Limburg, were annexed by Belgium according to the Treaty of Versailles. The cantons of Eupen, Malmedy and Sankt Vith though (with the exception of Malmedy) German in culture and language, became the East Cantons of Belgium. Although a plebiscite was held in early 1920, it was not conducted as a secret ballot, instead of requiring those opposed to Belgian annexation to formally register their protest. Only a few did so. Today German is the third official language of Belgium, along with French and Dutch.

During the occupation (1919–1930), the French encouraged the establishment of an independent Rhenish Republic, banking on traditional anti-Prussian resentments (see: history of Palatinate). In the end, the separatists failed to gain any decisive support among the population.

The Treaty of Versailles also specified the de-militarization of the entire area to provide a buffer between Germany on one side and France, Belgium and Luxembourg (and to a lesser extent, the Netherlands) on the other side, which meant that no German forces were allowed there after the Allied forces had withdrawn. Furthermore, (and quite unbearably from the German perspective) the treaty entitled the Allies to reoccupy the Rhineland at their will if the Allies unilaterally found the German side responsible for any violation of the treaty.

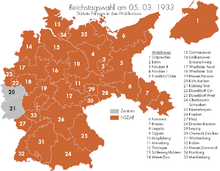

In the last free German federal election in March 1933, two of the four parliamentary districts of the Rhine Province (Cologne-Aachen and Koblenz-Trier) were the only districts in Germany where the Nazi Party did not win the plurality of votes.

In violation of the Treaty of Versailles and the spirit of the Locarno Pact, Nazi Germany remilitarized the Rhineland on Saturday, March 7, 1936. The occupation was done with very little military force, the troops entering on tractors, and no effort was made to stop it (see Appeasement of Hitler), even though the French had an overwhelming force nearby. France could not act due to political instability at the time, and, since the remilitarization occurred at a weekend, the British government could not find out or discuss actions to be taken until the following Monday. As a result of that, the governments were inclined to see the remilitarization as a fait accompli.

Adolf Hitler took a risk when he sent his troops to the Rhineland. He told them to "turn back and not to resist" if they were stopped by the French Army. The French, however, did not try to stop them because they were currently holding elections and the president did not want to start a war with Germany.

The British government did not oppose the act in principle, feeling with Lord Lothian that "the Germans are after all only going into their own back garden"[5] but rejected the Nazi manner of accomplishing the act. Winston Churchill, however, advocated military action through cooperation by the British and French. The remilitarization of the Rhineland was favoured by some of the local population, because of a resurgence of German nationalism and harboured bitterness over the Allied occupation of the Rhineland until 1930 (Saarland until 1935).

A side-effect of the French occupations was the offspring of French soldiers and German women. These children, who were seen as the continuing French pollution of German culture, were shunned by the broader German society and were known as Rhineland Bastards. Children fathered by French colonial troops of African ancestry were especially despised and became targets of the Nazi sterilisation programmes in the 1930s. The American poet Charles Bukowski was born in 1920 in Andernach as the son of a German mother and a Polish-American U.S. soldier, serving among the occupation troops and soldiers.

1944–1945 military campaigns

Two different military campaigns were fought in the Rhineland.

U.S. Army

The first operation of the campaign was the Allied Operation Market Garden that sought to allow the Second British Army to advance past the northern flank of the Siegfried Line and enter the Ruhr industrial area. After the failure of that operation for five months, from September 1944 until February 1945, the First United States Army fought a costly battle to capture the Hürtgen Forest. The heavily forested and ravined terrain of the Hürtgen negated Allied combined arms advantages (close air support, armor, artillery) and favoured German defenders. The U.S. Army lost 24,000 troops. The military necessity of their sacrifice has been debated by military historians.

Canadian Army

In early 1945, after a long winter stalemate, military operations by most Allied armies in Northwest Europe resumed with the goal of reaching the Rhine. From their winter positions in The Netherlands, the First Canadian Army under General Henry Crerar reinforced by elements of the British Second Army under General Miles Dempsey, drove through the Rhineland beginning in the first week of February 1945.

Operation Veritable lasted several weeks, with the end result of clearing all German forces from the west side of the Rhine river. The supporting operation by the First US Army, Operation Grenade, was planned to coincide from the River Roer, in the south. This was delayed for two weeks, however, by German flooding of the Roer valley.

Other actions

On March 7, 1945, a company of armoured infantry of the U.S. 9th Armored Division captured the last intact bridge over the Rhine at Remagen. General George Patton's Third US Army also made a crossing of the river the day before the much anticipated Rhine crossings by the 21st Army Group (First Canadian Army and the British Second Army) under Field Marshal Montgomery in the third week of March 1945.

Operation Varsity was a massive airborne operation in conjunction with Operation Plunder, the amphibious crossings. By early April, the Rhine had been crossed by all the Allied armies operating west of the river, and the battles for the Rhineland were over.

Battle honours

In the official histories of the British and Canadian armies, the term Rhineland refers only to fighting west of the river in February and March 1945, with subsequent operations on the river and to the east known as "Rhine Crossing". Both terms are official Battle Honours in the Commonwealth forces.

In 1946, the Rhine Province was divided into the newly founded states of Hesse, North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate.

Notes

- Chisholm 1911, p. 242.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 243.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 242–243.

- "The Congress of Vienna | Boundless World History". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- Shirer, William L. (1959). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (Paperback ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 293.

References

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 242–243.

Further reading

- Brophy, James M. Popular Culture and the Public Sphere in the Rhineland, 1800–1850 (2010) excerpt and text search

- Collar, Peter. The Propaganda War in the Rhineland: Weimar Germany, Race and Occupation after World War I (2013) excerpt and text search

- Diefendorf, Jeffry M. Businessmen and Politics in the Rhineland, 1789–1834 (1980)

- Emmerson, J.T. Rhineland Crisis, 7 March 1936 (1977)

- Ford, Ken; Brian, Tony (2000). The Rhineland 1945: The Last Killing Ground in the West. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 1-85532-999-9.

- Marsden, Walter (1973). The Rhineland. New York: Hastings House. ISBN 0-8038-6324-1.

- Rowe, Michael, From Reich to State: The Rhineland in the Revolutionary Age, 1780–1830 (2007) excerpt and text search

- Sperber, Jonathan. Rhineland Radicals: The Democratic Movement and the Revolution of 1848–1849 (1992)

External links