Solomon Northup

Solomon Northup (born July 10, 1807 or 1808) was an American abolitionist and the primary author of the memoir Twelve Years a Slave. A free-born African American from New York, he was the son of a freed slave and a free woman of color. A farmer and a professional violinist, Northup had been a landowner in Hebron, New York. In 1841, he was offered a traveling musician's job and went to Washington, D.C. (where slavery was legal); there he was drugged, kidnapped, and sold as a slave. He was shipped to New Orleans, purchased by a planter, and held as a slave for 12 years in the Red River region of Louisiana, mostly in Avoyelles Parish. He remained a slave until he met a Canadian working on his plantation who helped get word to New York, where state law provided aid to free New York citizens who had been kidnapped and sold into slavery. His family and friends enlisted the aid of the Governor of New York, Washington Hunt, and Northup regained his freedom on January 3, 1853.[1]

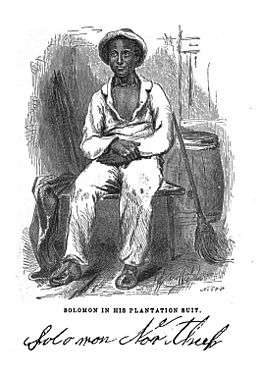

Solomon Northup | |

|---|---|

Engraving from his autobiography | |

| Born | Solomon Northup[Note 1] July 10, 1807 or 1808 Minerva, New York, U.S. |

| Died | between 1857 and 1875 |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Raftsman, fiddler, laborer, carpenter |

| Known for | Twelve Years a Slave |

| Signature | |

The slave trader in Washington, D.C., James H. Birch, was arrested and tried, but acquitted because District of Columbia law prohibited Northup as a black man from testifying against white people. Later, in New York State, his northern kidnappers were located and charged, but the case was tied up in court for two years because of jurisdictional challenges and finally dropped when Washington, D.C. was found to have jurisdiction. The D.C. government did not pursue the case. Those who had kidnapped and enslaved Northup received no punishment.

In his first year of freedom, Northup wrote and published a memoir, Twelve Years a Slave (1853). He lectured on behalf of the abolitionist movement, giving more than two dozen speeches throughout the Northeast about his experiences, to build momentum against slavery. He largely disappeared from the historical record after 1857, although a letter later reported him alive in early 1863;[2] some commentators thought he had been kidnapped again, but historians believe it unlikely, as he would have been considered too old to bring a good price.[3] The details of his death have never been documented.[4]

Northup's memoir was adapted and produced as the 1984 television film Solomon Northup's Odyssey and the 2013 feature film 12 Years a Slave. The latter won three Academy Awards, including Best Picture, at the 86th Academy Awards.

Early life

Family history

Solomon Northup was born on July 10, 1807 or in 1808.[5][6] His father Mintus was a freedman who had been a slave in his early life in service to the Northup family. Born in Rhode Island, he was taken with the Northups when they moved to Hoosick, New York, in Rensselaer County. His master, Capt. Henry Northup, a great grandson of Stephen Northup, manumitted Mintus in his will.[7][8] After being freed by Henry Northup, Mintus adopted the surname Northup as his own. The name appears interchangeably in records as Northup and Northrup.

Mintus Northup married and moved with his wife, a free woman of color, to the town of Minerva in Essex County, New York. Their two sons, Solomon and Joseph, were born free according to the principle of partus sequitur ventrem, as their mother was a free woman.[Note 2][9] Solomon described his mother as a quadroon, meaning that she was one-quarter African, and three-quarters European.[10] A farmer, Mintus Northup was successful enough to own land and thus meet the state's property requirements. From 1821 on, when it revised its constitution, the state retained the property requirement for black people, but dropped it for white men, thus expanding their franchise. It is notable that Mintus Northup was able to save enough money as a freedman to buy land that satisfied this requirement, and registered to vote.[Note 3][8] He provided an education for his two sons at a level considered high for free black people at that time.[11] As boys, Northup and his brother worked on the family farm.[5][8] Mintus and his wife last lived near Fort Edward. He died on November 22, 1829,[8] and his grave is in Hudson Falls Baker Cemetery.

Marriage and family

In 1828 or 1829,[Note 4][5][8] Solomon Northup married Anne Hampton. A "woman of color", she was of African, European, and Native American descent.[12] Between 1830 and 1834, the couple lived in Fort Edward and Kingsbury, small communities in Washington County, New York.[13]

They had three children: Elizabeth, Margaret, and Alonzo.[14] They owned a farm in Hebron and supplemented their income by various jobs. In his later memoir, Northup describes his love for his wife as "sincere and unabated", since the time of their marriage, and his children as "beloved".[15]

Work

Northup held various jobs, including working as a raftsman. He built a fine reputation as a fiddler and was in high demand to play for local dances. Anne became notable as a cook and worked for local taverns, which served food and drink.[8]

After selling their farm in 1834, the Northups moved 20 miles to Saratoga Springs, New York,[16] for its employment opportunities.[5][8] Northup played his violin at several well-known hotels in Saratoga Springs, though he found its seasonal cycles of employment difficult. He was busy during the summer, but work was scarce at other times. He worked at an assortment of jobs, constructing the Champlain Canal and the railroad, and as a skilled carpenter. Anne worked from time to time as a cook at the United States Hotel and other public houses, and she was highly praised for her culinary skills. When court was in session at the county seat of Fort Edward, she worked at Sherrill's Coffee House in Sandy Hill (now Hudson Falls) to earn extra money.[17][18]

Kidnapped and sold into slavery

In 1841, at age 32, Northup met two men, who introduced themselves as Merrill Brown and Abram Hamilton. Saying they were entertainers, members of a circus company, they offered him a job as a fiddler for several performances in New York City.[5][8] Expecting the trip to be brief, Northup did not notify Anne, who was working in Sandy Hill.[19] When they reached New York City, the men persuaded Northup to continue with them for a gig with their circus in Washington, D.C., offering him a generous wage and the cost of his return trip home. They stopped so that he could get a copy of his "free papers", which documented his status as a free man.[8] His status was a concern as he was traveling to Washington, where slavery was legal.

The city had one of the nation's largest slave markets, and slave catchers were not above kidnapping free black people.[20] At this time, 20 years before the Civil War, the expansion of cotton cultivation in the Deep South had led to a continuing high demand for healthy slaves. Kidnappers used a variety of means, from forced abduction to deceit, and frequently abducted children, who were easier to control.[21]

It is possible that "Brown" and "Hamilton" incapacitated Northup—his symptoms suggest that he was drugged with belladonna or laudanum, or with a mixture of both[22]—and sold him to Washington slave trader James H. Birch[Note 5] for $650, claiming that he was a fugitive slave.[8][14] However, Northup stated in his account of the ordeal in Twelve Years a Slave in Chapter II, "[w]hether they were accessory to my misfortunes – subtle and inhuman monsters in the shape of men – designedly luring me away from home and family, and liberty, for the sake of gold – those who read these pages will have the same means of determining as myself." Birch and Ebenezer Radburn, his jailer, severely beat Northup to stop him from saying he was a free man. Birch then wrongfully presented Northup as a slave from Georgia.[23] Northup was held in the slave pen of trader William Williams, close to the United States Capitol.[14] Birch shipped Northup and other slaves by sea to New Orleans, in what was called the coastwise slave trade, where Birch's partner Theophilus Freeman would sell them.[5][8] During the voyage, Northup and the other slaves caught smallpox.[14] A slave named Robert died of the disease en route.

Northup persuaded John Manning, an English sailor, to send to Henry B. Northup, upon reaching New Orleans, a letter that told of his kidnapping and illegal enslavement.[24] Henry was a lawyer, the son of the man who had once held Solomon's father as a slave and freed him, and a childhood friend of Solomon's. The New York State Legislature had passed a law in 1840 to protect its African-American residents by providing legal and financial assistance to aid the recovery of any who were kidnapped and taken out of state and illegally enslaved.[21] Henry Northup was willing to help but could not act without knowing where Solomon was held.

At the New Orleans slave market, Birch's partner Theophilus Freeman sold Northup (who had been renamed Platt) along with Harry and Eliza (renamed Dradey) [26] to William Prince Ford, a preacher who engaged in small farming on Bayou Boeuf of the Red River in northern Louisiana.[5][8] Ford was then a Baptist preacher. (In 1843, he led his congregation in converting to the closely related Churches of Christ, after they were influenced by the writings of Alexander Campbell.) In his memoir, Northup characterized Ford as a good man, considerate of his slaves. In spite of his situation, Northup wrote:

In my opinion, there never was a more kind, noble, candid, Christian man than William Ford. The influences and associations that had always surrounded him, blinded him to the inherent wrong at the bottom of the system of Slavery.[8]

At Ford's place in Pine Woods, Northup assessed the problem of getting timber off Ford's farm to market. He proposed making log rafts to move lumber down the narrow Indian Creek, in order to transport the logs more easily and less expensively than overland. He was familiar with this process from previous work in New York, and Ford was delighted to see his project was a success. Northup used his carpentry skills to build looms, copying from one nearby, so that Ford could set up mills on the creek. With Ford, Northup found his efforts appreciated. But the planter came into financial difficulties and had to sell 18 slaves to settle his debts. He sold 17 to a neighboring planter named Compton. Solomon could not pick cotton, however, so Ford found a buyer in a local tradesman.

In the winter of 1842, Ford sold Northup to John M. Tibaut,[8][Note 6] a carpenter who had been working for Ford on the mills. He also had helped construct a weaving-house and corn mill on Ford's Bayou Boeuf plantation. Ford owed Tibaut money for the work. Since the amount Ford owed Tibaut was less than the purchase price agreed upon for Solomon, Ford held a chattel mortgage on Northup for $400, the difference between the two amounts.[27]

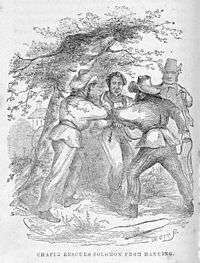

Under Tibaut, Northup suffered cruel and capricious treatment. Tibaut used him to help complete construction at Ford's plantation. At one point, Tibaut whipped Northup because he did not like the nails Northup was using. But Northup fought back, beating Tibaut severely. Enraged, Tibaut recruited two friends to lynch and hang the slave, which a master was legally entitled to do. Ford's overseer Chapin interrupted and prevented the men from killing Northup, reminding Tibaut of his debt to Ford, and chasing them off at gunpoint. Northup was left bound and noosed for hours until Ford returned home to cut him down.[28] Northup believed that Tibaut's debt to Ford saved his life. Historian Walter Johnson suggests that Northup may well have been the first slave Tibaut ever bought, marking his transition from itinerant employee to property-owning master.[29]

Tibaut, who had a low reputation locally, decided at another point to kill Northup. When the two men were alone, Tibaut seized an axe and swung it to hit Northup, but he again defended himself. With his bare hands, he strangled Tibaut to the point of unconsciousness. Northup ran away through swamps so that dogs could not track him, making his way back to Ford, with whom he stayed for four days. The planter convinced Tibaut to "hire out" Northup to limit their conflict and take the fees he could generate.

Tibaut hired Northup out to a planter named Eldret, who lived about 38 miles south on the Red River. At what he called "The Big Cane Brake", Eldret had Northup and other slaves clear cane, trees, and undergrowth in the bottomlands in order to develop cotton fields for cultivation.[14][30] With the work unfinished, after about five weeks, Tibaut sold Northup to Edwin Epps.

Epps held Northup for almost 10 years, until 1853, in Avoyelles Parish. He was a cruel master who frequently and indiscriminately punished slaves and drove them hard. His policy was to whip slaves if they did not meet daily work quotas he set for pounds of cotton to be picked, among other goals.[31] Northup wrote that the sounds of whipping were heard every day on Epps' plantation, from sundown until lights out. Epps sexually abused a young enslaved woman named Patsey, repeatedly raping her. This led to additional severe physical and mental abuse prompted by Epps's wife, the mistress of the plantation.

In 1852, itinerant Canadian carpenter Samuel Bass came to do some work for Epps. Hearing Bass express his abolitionist views, Northup eventually decided to confide his secret to him. Bass was the first person he told of his true name and origins as a free man since he was first enslaved.[32] Along with mailing a letter written by Northup, Bass wrote several letters at his request to Northup's friends, providing general details of his location at Bayou Boeuf, in hopes of gaining his rescue.[33]

Bass did this at great personal risk as the local people would not take kindly to a person helping a slave and depriving a man of his property. In addition, Bass's help came after passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which increased federal penalties against people assisting slaves to escape.[34]

Restoration of freedom

Bass wrote several letters: one reached Cephas Parker and William Perry, storekeepers in Saratoga who knew Northup. Parker or Perry forwarded the letter to Northup's wife, Anne, who contacted attorney Henry B. Northup, the son of Solomon's father's former master. Henry B. Northup contacted New York Governor Washington Hunt, who took up the case, appointing the attorney general as his legal agent. In 1840, the New York State Legislature had passed a law committing the state to help any African-American residents kidnapped into slavery, as well as guaranteeing a jury trial to alleged fugitive slaves. Once Northup's family was notified, his rescuers still had to do detective work to find the enslaved man, as he had partially tried to hide his location for protection in case the letters fell into the wrong hands, and Bass had not used his real name. They had to find documentation of his free status as a citizen and New York resident; Henry B. Northup also collected sworn affidavits from people who knew Solomon Northup. During this time, Northup did not know if Bass had reached anyone with the letters. There was no means of communicating, because of the secrecy they needed to maintain, and the necessity of preventing Northup's owner from knowing their plans.[8][18]

Bass was itinerant and had no local family. (Unbeknownst to his friends in Louisiana, he had left a wife and children in Canada.[34] He also lived with a free woman of color in Louisiana.[34]) Because of the risk, Bass did not reveal his own name in the letter. Henry Northup still managed to find him in Louisiana, and Bass revealed that Solomon Northup was held by Edwin Epps on his plantation.[35] Henry B. Northup took the precaution of bringing with him the sheriff of Marksville, the parish seat, to enforce the law.

In cooperation with U.S. Senator Pierre Soulé from Louisiana and other local authorities, Henry B. Northup arrived in Marksville on January 1, 1853. Tracing Northup was difficult as he was known locally only by his slave name of Platt. When the attorney confronted Epps with the evidence that Platt/Northup was a free man, with a wife and children, Epps first demanded of the enslaved man why he had not told him this at the time of purchase. Then Epps said, had he known that men were coming to take "Platt", he would have ensured they could never take the slave alive. Epps cursed the man (unknown to him) who had helped Northup, and threatened to kill him if he ever learned his identity.

Northup later wrote, "He [Epps] thought of nothing but his loss, and cursed me for having been born free."[8][36] Attorney Henry B. Northup convinced Epps that it would be futile to contest the free papers in a court of law, so the planter conceded the case. He signed papers giving up all claim to Northup. Finally on January 4, 1853, four months after meeting Bass, Northup regained his freedom.[14][37]

Court cases and memoir

Northup was one of the few kidnapped free black people to regain freedom after being sold into slavery. Represented by attorneys Senator Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, General Orville Clark, and Henry B. Northup, Solomon Northup sued Birch and other men involved in selling him into slavery in Washington, DC.[Note 7][1][3]

As Solomon Northup and Henry Northup made their way back to New York, they first stopped in Washington DC to file a legal complaint with the police magistrate against James H. Birch, the man who had first enslaved him. Birch was immediately arrested and tried on criminal charges. However, Northup was unable to testify at the trial due to laws in Washington DC against black men testifying in court. Birch and several others, who were also in the slave trade, testified that Northup had approached them, saying he was a slave from Georgia and was for sale. No note of his purchase was made in Birch's accounting ledger, however. The prosecution consisted of Henry B. Northup and another white man asserting that they had known Northup for many years, and he was born and lived a free man in New York until his abduction. With no one legally able to testify against Birch's tale, Birch was found not guilty. However, the sensational case immediately attracted national attention, and The New York Times published an article about the trial on January 20, 1853, just days after its conclusion and only two weeks after Northup's rescue.[1][38]

Following his acquittal, Birch demanded charges be filed against Solomon Northup for trying to defraud him of Northup's $625 purchase price by falsely claiming he was a Georgia slave for sale. Northup, eager to prove the veracity of his own story, urged the trial to proceed. Upon the advice of his lawyer, Birch withdrew the complaint, against the protests of Northup. Northup knew that a trial related to Birch's complaint could only rebound against Birch and make him look bad. If Northup had in fact claimed to be a slave from Georgia, it would not have made sense for him to risk his freedom, days after regaining it, by contacting the law to bring charges against Birch.

At the time, Northup did not file a legal complaint against the men with the circus, Alexander Merrill and Joseph Russell, because they could not be found, having used false names with Northup. At first, Northup had trouble believing they could be complicit.

Later that same year, Solomon Northup wrote and published his memoir, Twelve Years a Slave (1853). The book was written in three months with the help of David Wilson, a local writer and journalist.[3] Published by Derby & Miller of Auburn, New York[39] In the period when questions of slavery generated debate and the novel Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852) by Harriet Beecher Stowe was a bestseller, Northup's book sold 30,000 copies within three years, also becoming a bestseller.[3]

When the book and case were publicized, Thaddeus St. John, a county court judge in nearby Fonda, New York, recalled having seen two old friends, Alexander Merrill and Joseph Russell, traveling with a black man to Washington, DC at the time of the late President Harrison's funeral in 1841. He saw them again while returning from Washington, but they were without the black man. They wore and carried new extravagantly expensive items, and he recalled an odd conversation with them during the first trip. They had asked him then to call them Brown and Hamilton when in company with the black man, rather than Merrill and Russell, as he knew them. After contacting authorities, St. John met with Northup. The two recognized each other from the first encounter on the train in 1840. With this identification, Merrill and Russell were located and arrested.

The New York trial opened on October 4, 1854. Both Northup and St. John testified against the two men. The case brought widespread illegal practices in the domestic slave trade to light. Through testimony during the court case, various details of Northup's account of his experience were confirmed.[8] The respective counsels argued over whether the crime had been committed in New York (where Northup could testify), or in Washington, DC, outside the jurisdiction of New York courts. After more than two years of appeals, a new district attorney in New York failed to continue with the case, and it was dropped in May 1857.[8][40] Washington, DC authorities declined to prosecute Merrill and Russell, and no further legal action was taken against those who had allegedly kidnapped and sold Northup into slavery.

Last years

After regaining his freedom, Solomon Northup rejoined his wife and children. By 1855, he was living with his daughter Margaret Stanton and her family in Queensbury, Warren County, New York.[41] He was working again as a carpenter. He became active in the abolitionist movement and lectured on slavery on nearly two dozen occasions throughout the northeastern United States in the years before the American Civil War.[42][43]

During the summer of 1857, Northup was in Canada for a series of lectures. It was widely reported that Northup was in Streetsville, Ontario, but that a hostile Canadian crowd prevented him from speaking.[44] There is no contemporaneous documentation of his whereabouts after that time.[4] The location and circumstances of his death are unknown.[45] Rumors ran rife. In 1858, a newspaper reported, "It is said that Solomon Northup, who was kidnapped, sold as a slave, and afterwards recovered and restored to freedom has been again decoyed South, and is again a slave."[46] Shortly thereafter, even his benefactor Henry B. Northup is said to have believed Solomon had been kidnapped from Canada while drunk.[47]

Years later, in The Bench and Bar of Saratoga County (1879), E. R. Mann mistakenly wrote that the Saratoga County kidnapping case against Merrill and Russell had been dismissed because Northup had disappeared. Mann speculated, "What his fate was is unknown to the public, but the desperate kidnappers no doubt knew."[48] In 1909, John Henry Northup, Henry's nephew, wrote: "The last I heard of him, Sol was lecturing in Boston to help sell his book. All at once, he disappeared. We believe that he was kidnapped and taken away or killed."[3] According to John R. Smith, in letters written in the 1930s, he said that his father Rev. John L. Smith, a Methodist minister in Vermont, had worked with Northup and former slave Tabbs Gross in the early 1860s, during the Civil War, aiding fugitive slaves on the Underground Railroad.[2] Northup was said to have visited Rev. Smith after Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, which was made in January 1863.[2]

Northup was not listed with his family in the 1860 United States Census.[49] The New York state census of 1865 records his wife Anne Northup (but not Solomon); she was recorded as married, not widowed, and living with their daughter and son-in-law, Margaret and Philip Stanton, in nearby Moreau in Saratoga County.[50] In 1870, Northup's wife was enumerated as a cook in the household of Burton C. Dennis.[51] At the time, Dennis kept the Middleworth House hotel in Sandy Hill, New York. Solomon Northup is not listed among those living at the hotel. That same year, his daughter, Margaret Stanton, and his son-in-law appear in the census schedule for Moreau, New York,[52] but Northup's name is not there, either. Northup's son, Alonzo, is included in the 1870 census for Fort Edward, New York; his household includes only him, his wife and his daughter.[53]

In 1875, Anne Northup was living in Kingsbury/Sandy Hill in Washington County, New York,[54] and, in census information, her marital status was given as "now widowed." When Anne Northup died in 1876, some newspaper notices of her death said that she was a widow. One obituary, while praising Anne, says of Solomon Northup that "after exhibiting himself through the country [he] became a worthless vagabond".[55]

The 21st-century historians Clifford Brown and Carol Wilson believe it is likely that he died of natural causes.[3] They think a kidnapping for slavery in the late 1850s was unlikely, as he was too old to be of interest to slave catchers, but his disappearance remains unexplained.[4]

Historiography

Although the memoir is often classified among the genre of slave narratives, the scholar Sam Worley says that it does not fit the standard format of the genre. Northup was assisted in the writing by David Wilson, a white man, and, according to Worley, some believed he would have biased the material. Worley discounted concerns that Wilson was pursuing his own interests in the book. He writes of the memoir:

Twelve Years is convincingly Northup's tale and no one else's because of its amazing attention to empirical detail and unwillingness to reduce the complexity of Northup's experience to a stark moral allegory.[18]

Northup's biographer, David Fiske, has investigated Northup's role in the book's writing and asserts authenticity of authorship.[56] Northup's full and descriptive account has been used by numerous historians researching slavery. His description of the "Yellow House" (also known as "The Williams Slave Pen"), in view of the Capitol, has helped researchers document the history of slavery in the District of Columbia.[Note 8]

Influence among scholars

- Northup's memoir was reprinted in 1869.[57]

- Ulrich B. Phillips, in his Life and Labor in the Old South (Boston, 1929) and American Negro Slavery (New York, 1918), doubted the "authenticity" of most narratives of ex-slaves but termed Northup's memoir "a vivid account of plantation life from the under side".[58][59]

- The scholar Kenneth M. Stampp often referred to Northup's memoir in his book on slavery, The Peculiar Institution (New York, 1956).[60][61] Stanley Elkins in his book, Slavery (Chicago, 1959), like Phillips and Stampp, found Northup's memoir to be of credible historical merit.[59]

- Since the mid-20th century, the civil rights movement, and an increase in works of social history and in African-American studies, have brought renewed interest in Northup's memoir.[62]

- The first scholarly edition of the memoir was published in 1968.[63] Co-edited by professors Sue Eakin and Joseph Logsdon, this well-annotated LSU Press publication has been used in classrooms and by scholars since that time and is still in print.[62]

- In 1998, a team of students at Union College in Schenectady, New York, with their political science professor Clifford Brown, documented Northup's historic narrative. "They gathered photographs, family trees, bills of sale, maps and hospital records on a trail through New York, Washington [DC] and Louisiana."[3] Their exhibit of this material was held at the college's Nott Memorial building.[3]

- In his book Black Men Built the Capitol (2007), Jesse Holland notes his use of Northup's account.[64][Note 9]

Legacy and honors

- In 1999, Saratoga Springs erected a historical marker at the corner of Congress and Broadway to commemorate Northup's life. The city later established the third Saturday in July as Solomon Northup Day, to honor him, bring regional African-American history to light, and educate the public about freedom and justice issues.[65][66]

- In 2000, the Library of Congress accepted the program of Solomon Northup Day into the permanent archives of the American Folklife Center. The Anacostia Community Museum and the National Park Service-Network to Freedom Project[67] have also recognized the merits of this multi-venue, multi-cultural event program. "Solomon Northup Day – a Celebration of Freedom" continues annually in the City of Saratoga Springs, as well as in Plattsburgh, New York, with the support of the North Country Underground Railroad Historical Association.[68]

- Annual observances have been made to honor Solomon Northup. A 2015 conference at Skidmore College had a gathering of Northup's descendants, and the speakers included Congressman Paul D. Tonko.[69]

Representation in media

- Former U.S. poet laureate and Pulitzer Prize winner Rita Dove wrote the poem "The Abduction" about Northup, published in her first collection, The Yellow House on the Corner (1980).[70]

- 1984, Twelve Years a Slave was adapted as a PBS television movie titled Solomon Northup's Odyssey, directed by Gordon Parks. Northup was portrayed by Avery Brooks.[71]

- In 2008, composer and saxophonist T. K. Blue, commissioned by the New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA), recorded Follow the North Star, a musical composition inspired by Northup's life.[72]

- The episode "Division" of the 2010 television miniseries America: The Story of Us depicts Northup's slave auction. Significant emphasis is placed on Eliza being separated from her children, and the actor portraying Northup does voiceover of direct passages from Twelve Years a Slave.

- The 2013 feature film 12 Years a Slave, adapted from his memoir, was written by John Ridley and directed by Steve McQueen.[73] British actor Chiwetel Ejiofor portrays Northup, for which he earned an Oscar nomination for Best Actor in a Leading Role. The film was nominated for nine Academy Awards,[74] winning 3—for Best Picture, Best Adapted Screenplay, for John Ridley,[75] and Best Supporting Actress for Lupita Nyong'o, who played the slave Patsey in her debut film role.[75]

See also

Notes

- In early newspaper articles, the name is spelled both "Northrop"and "Northrup", sometimes both spellings occurring in the same article.

- Although Northup gives his year of birth as 1808 in his book, in sworn testimony in 1854, he said he had reached the age of 47 on July 10 that year, making his year of birth 1807, which is consistent with a statement by his wife in 1852 that he was "about 45".

- "Transcription of New York Constitution of 1821 excerpt". New York State Archives. Archived from the original on December 31, 2013.

- Northup's text Twelve Years a Slave gives the date as 1829; however, his wife and the Justice of the Peace who performed the wedding gave the year as 1828. See "Memorial of Anne," and statement of Timothy Eddy, both in Appendix B of Twelve Years a Slave

- Birch is spelled as Burch in Northup's book

- The name is spelled as "Tibeats" in Northup's book, which is likely the way it was pronounced locally.

- The historian Carol Wilson documented 300 kidnapping cases in her 1994 book, Freedom at Risk: The Kidnapping of Free Blacks in America, 1780–1865. Freedom at Risk: The Kidnapping of Free Blacks in America, 1780–1865, University of Kentucky Press, 1994. She believes it is likely that thousands more were kidnapped who were never documented.

- Northup described the slave pen owned by William Williams in Washington: "It was like a farmer's barnyard in most respects, save it was so constructed that the outside world could never see the human cattle that were herded there. The building to which the yard was attached, was two stories high, fronting on one of the public streets of Washington. Its outside presented only the appearance of a quiet private residence. A stranger looking at it, would never have dreamed of its execrable uses. Strange as it may seem, within plain sight of this same house, looking down from its commanding height upon it, was the Capitol. The voices of patriotic representatives boasting of freedom and equality, and the rattling of the poor slave's chains, almost commingled. A slave pen within the very shadow of the Capitol! Such is a correct description as it was in 1841, of Williams' slave pen in Washington, in one of the cellars of which I found myself so unaccountably confined." "Free blacks kidnapped, sold into slavery in the shadow of the U.S. Capitol", Washington Times October 20, 2013

- Another slave market was located at Robey's Tavern; these sites were located on what is now the Mall between the present-day Department of Education and the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, within view of the Capitol.

References

- "The Kidnapping Case: Narrative of the Seizure and Recovery of Solomon Northrup" (PDF). The New York Times. January 20, 1853. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- "John R. Smith letter" (1930s), Wilbur Henry Siebert collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University "Wilbur Henry Siebert Collection". Archived from the original on April 3, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- Genz, Michelle (March 7, 1999). "Solomon's Wisdom". Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 16, 2005. Retrieved February 19, 2012.

- Lo Wang, Hansi. "'12 Years' Is The Story Of A Slave Whose End Is A Mystery". NPR. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- Chisholm, Hugh (1911). "Solomon Northup". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Nelson, Emmanuel Sampath (2002). "Solomon Northup (1808-1863?)". In Marsden, Elizabeth (ed.). African American Autobiographers: A Sourcebook. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 290. ISBN 9780313314094.

- "Last Will & Testament of Henry Northrop" (recorded October 3, 1797), Rensselaer County, New York Will Book, vol 1, pp 144–145. Accessed October 22, 2013.

- "Oxford AASC: Home".

- "The Northup Kidnapping Case," New York Daily Tribune, July 14, 1854, p. 7; "Memorial of Anne," appendix to Twelve Years a Slave

- Northup, Solomon; David Wilson. Twelve Years a Slave, Auburn, NY: Orton and Mulligan; London: Samson Low, Son & Company, 1853, p. 1, at Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina

- Curtis, Nancy. Black Heritage Sites: the South, 1996, p. 118.

- Northup (1853), Twelve Years a Slave, p. 21

- "Solomon Northup, Kingsbury, Washington, New York". United States Census, 1830. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- African American Autobiographers: A Sourcebook (2002) Ed. Emmanuel S. Nelson, Greenwood Press, p. 291

- Northrup, Solomon; edited by Sue Eakin & Joseph Logsdon (1968). Twelve Years a Slave. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 7. ISBN 0807101508.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Solomon Northorp, Saratoga Springs, Saratoga, New York". United States Census, 1840. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- Northup (1853), Twelve Years, pp. 25, 28

- Worley, Sam. "Solomon Northup and the Sly Philosophy of the Slave Pen", Callaloo, Vol. 20, No. 1 (Winter 1997), p. 245.

- Northup (1853), Twelve Years a Slave, p. 30

- "Researching the African-American Experience in Washington, D.C." George Washington University. Gelman Library System. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- Wilson, Carol (1994). Freedom at Risk. University of Kentucky Press. pp. 10–12.

- Fradin, Judith Bloom; Fradin, Dennis Brindell (2012). Stolen into Slavery: The True Story of Solomon Northup, Free Black Man. National Geographic Books. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-4263-0937-3.

- Northup, Solomon (1853). Twelve Years a Slave. p. 36.

- Northup, Solomon (1969) [1853]. Osofsky, Gilbert (ed.). Puttin' On Ole Massa: The Slave Narratives of Henry Bibb, William Wells Brown, and Solomon Northup. Harper & Row. p. 260. LCCN 69017285.

- New Orleans Notarial Archives

- Northup, Solomon (1853). Twelve Years a Slave. pp. 84–85.

- Northup, Solomon (1853). Twelve Years a Slave. pp. 105–106.

- Northup, Solomon (1853). Twelve Years a Slave. pp. 114–116.

- Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market, (1999) Walter Johnson, Harvard University Press, p. 80

- Northup, Solomon (1853). Twelve Years a Slave. pp. 153–156.

- Northrup, Solomon; edited by Sue Eakin & Joseph Logsdon (1968). Twelve Years a Slave. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. pp. 125–126. ISBN 0807101508.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Northrup, Solomon; edited by Sue Eakin & Joseph Logsdon (1968). Twelve Years a Slave. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. pp. 211–212. ISBN 0807101508.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Fiske, David; Clifford W. Brown Jr. (August 12, 2013). Solomon Northup: The Complete Story of the Author of Twelve Years a Slave. ABC-CLIO. pp. 15–18. ISBN 978-1-4408-2975-8.

- Szklarski, Cassandra (November 15, 2013). "Canadian connection to 12 Years a Slave has descendants buzzing". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup, p.298

- Northup, Solomon (1853). Twelve Years a Slave. p. 184.

- Northup, Solomon (1853). Twelve Years a Slave. pp. 73–74, 270–73, 275, 292, 297–98.

- "Narrative of the Seizure and Recovery of Solomon Northrup". New York Times. Documenting the American South. University of North Carolina. January 20, 1853.

- J.C. Derby (1884), "William H. Seward", Fifty Years Among Authors, Books and Publishers, New York: G.W. Carleton & Co., pp. 62–63

- Fiske, David (2012). Solomon Northup: His Life Before and After Slavery. ISBN 1468096370.

- "Solomon Northup, Queensbury, Warren, New York". New York, State Census, 1855. New York Secretary of State. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- Fiske, David. Solomon Northup: His Life Before and After Slavery, 2012, Appendix A.

- Fiske, David; Brown, Clifford W.; Seligman, Rachel. Solomon Northup: The Complete Story of the Author of Twelve Years a Slave.

- "Freedom in Canada". Boston Herald. August 25, 1857. p. 2.

- "Death of Solomon Northup, author of 12 Years A Slave, still a mystery". The National. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- American Union (Ellicottville, NY), November 12, 1858

- "Poor Sol. Northop". Columbus (Georgia) Daily Enquirer. October 16, 1858. p. 2, citing the New York News.

- Mann, E. R. (1879). The Bench and Bar of Saratoga County. p. 153.

- "Ann Northup, Queensbury, Warren, New York". United States Census, 1860. NARA, Washington DC. Retrieved March 29, 2014.

- "New York, State Census, 1865 - Saratoga - Moreau". FamilySearch. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Images 21-22. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- 1870 Federal Census for Sandy Hill, Washington County, New York, Household #44

- 1870 Federal Census for Moreau, Saratoga County, New York, Household #100

- 1870 Federal Census for Fort Edward, Washington County, New York, Household #662

- "New York, State Census, 1875 > Washington > Kingsbury, E.D. 03". FamilySearch. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Image 16. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- "Vicinity News". Daily Albany Argus. August 16, 1876. p. 4.

- Fiske, David "Authenticity and Authorship: Solomon Northup's Twelve Years a Slave", New York State History Blog, David Fiske, December 11, 2013

- Ernest, John (2004). Liberation Historiography: African American Writers and the Challenge of History, 1794–1861. Chapel Hill: Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-8078-6353-4.

- Phillips, Ulrich Bonnell (2007) [1929]. Life and Labor in the Old South. Southern classics series. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. p. 219. ISBN 9781570036781. Retrieved May 5, 2014.

- Northrup, Solomon; edited by Sue Eakin & Joseph Logsdon (1968). Twelve Years a Slave. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. x. ISBN 0807101508.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Silbey, Joel H. "Review of Twelve Years a Slave by Solomon Northup, editors Sue Eakin and Joseph Logsdon", Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Vol. 63, No. 2 (Summer, 1970), p. 203.

- Stampp, Kenneth M. (1956). The Peculiar Institution. New York: Vintage Books. pp. 60, 74–5, 90, 162, 183, 285, 287, 323, 336–7, 359, 365, 380. Presence of "Twelve Years..." usually revealed by unindexed footnotes.

- "An Escape From Slavery, Now a Movie, Has Long Intrigued Historians". The New York Times. September 23, 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- Solomon Northup. "Twelve Years A Slave". Louisiana State University Press. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

- Holland, Jesse. "Black Men Built the Capitol", Democracy Now interview, January 20, 2009.

- City of Saratoga Springs. "Solomon Northup Day, A Celebration of Freedom". Press release carried at Saratoga NYGenWeb.

- Solomon Northup Day, in Saratoga Springs Heritage Area Visitor Center.

- "Freedom Project".

- "North Country Underground Railroad".

- Don Papson, "Solomon Northup Day 2015 Closing Remarks", Skidmore College, July 22, 2015

- "Rita Dove" at Facts On File, Encyclopedia of Black Women in America.

- "Solomon Northup's Odyssey". Fandor film site.

- "Follow the North Star". Allmusic.com.

- Kroll, Justin (October 11, 2011). "Fassbender, McQueen re-team for 'Slave'". Variety. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- "Oscars 2014: 12 Years a Slave must clean up. But that doesn't mean it will", Guardian, January 16, 2014

- Cieply, Michael; Barnesmarch, Brooks (March 2, 2014). "'12 Years a Slave' Claims Best Picture Oscar". The New York Times.

Further reading

- Fiske, David; Brown, Clifford W. & Seligman, Rachel (2013). Solomon Northup: The Complete Story of the Author of Twelve Years a Slave.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link), a complete biography of Northup

- Lester, Julius (1968). To Be a Slave. New York. pp. 39–58., Newbery Honor, ages 10 and up

- Osofsky, Gilbert, ed. (1969). Puttin' on Ole Massa: The Slave Narratives of Henry Bibb, William Wells Brown, and Solomon Northup. New York: Harper and Row. LCCN 69017285.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Solomon Northup. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Solomon Northup |

- Works by or about Solomon Northup at Internet Archive

- Works by Solomon Northup at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "The Kidnapping Case: Narrative of the Seizure and Recovery of Solomon Northrup" (PDF). The New York Times. January 20, 1853.

- Northup, Solomon; David Wilson. Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup, a Citizen of New-York, Kidnapped in Washington City in 1841, and Rescued in 1853, Auburn, N.Y.: Derby and Miller, 1853, at Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina.

- Letters by John R. Smith, "Wilbur H. Siebert Content", Houghton Library, Harvard University. Available as online images (Digital Collections tab), detailing Northup's involvement in the Underground Railroad after January 1863.

- Twelve Years a Slave, National Archives : Docs Teach

- The Solomon Northup Trail, LSU's Acadiana Historical project: maps and descriptions of sites from Northup's memoir, based on Eakin's and Logsdon's 1968 research.

- Twelve Years a Slave: Analyzing Slave Narratives, National Endowment for the Humanities EDSITEment lesson plan

- Faces of Solomon Some direct descendants of Solomon Northup

- Solomon Northup's Odyssey at the Internet Movie Database

- Genealogy of Solomon Northup's 4th generation descendent, Joseph M. Linzy Sr. - Chart 1

- Genealogy of Solomon Northup's 4th generation descendent, Joseph M. Linzy Sr. - Chart 2