Charles City County, Virginia

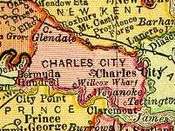

Charles City County is a county located in the U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. The county is situated southeast of Richmond and west of Jamestown. It is bounded on the south by the James River and on the east by the Chickahominy River.

Charles City County | |

|---|---|

Iona Whitehead-Adkins Courthouse | |

Seal | |

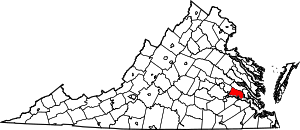

Location within the U.S. state of Virginia | |

Virginia's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 37°21′N 77°04′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1619 |

| Named for | Charles I of England |

| Seat | Charles City |

| Area | |

| • Total | 204 sq mi (530 km2) |

| • Land | 183 sq mi (470 km2) |

| • Water | 21 sq mi (50 km2) 10.5% |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 7,256 |

| • Estimate (2018) | 6,941 |

| • Density | 36/sq mi (14/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 4th |

| Website | www |

The area that would become Charles City County was first established as "Charles Cittie" by the Virginia Company in 1619. It was one of the first four "boroughs" of Virginia, and was named in honor of Prince Charles, who would later become King Charles I of England. After Virginia became a royal colony, the borough was changed to "Charles City Shire" in 1634, as one of the five original Shires of Virginia. It acquired the present name of Charles City County in 1643.

In the 21st century, Charles City County is part of the Greater Richmond Region of the state of Virginia. As of the 2010 census, the county population was 7,256; it is still relatively rural and one of smaller counties in Virginia by population.[1] Its county seat is the community of Charles City.[2]

Notable natives include the 9th and 10th Presidents of the United States, William Henry Harrison and John Tyler.

History

Native Americans

Various Indian tribes had used this area for thousands of years. When the region was explored by the English in the 17th century, the Algonquian-speaking Chickahominy tribe inhabited areas along the river that was later named for them by English colonists. The Paspahegh lived in Sandy Point, and the Weanoc lived in the Weyanoke Neck area. The latter two tribes were part of the Powhatan Confederacy. These three were all Algonquian-speaking tribes, the language family of the varied peoples who occupied the Tidewater and low country in Virginia and along the East Coast from Canada to south of the Carolinas.[3]

Algonquian was one of the three major language family groups of American Indians in Virginia. Other tribes located on lands in the interior spoke Siouan and Iroquoian languages.

English colonization

The English began to colonize the area under the auspices of the Virginia Company, a private company formed to support this effort and gain profits from expected development and trade. In 1619 the Virginia Company established Charles Cittie (sic) as one of the first four "boroughs" or "incorporations" in the region. West of James County, it was named for Prince Charles, second son of King James I of England, who became the Prince of Wales and heir apparent after the death of his older brother Henry in 1612. After his father's death, he became King Charles I of England.[4]

1619 marked the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in the Tidewater area. They had been captured from a Spanish ship and were taken to Weyanoke Peninsula. They were treated as indentured servants in the colony, and at least one later became a landowner after gaining his freedom. They created the first African community in what became the United States. Weyanoke, Virginia continues as a small, unincorporated community.

The Virginia Company lost its charter in 1624 under King James I, and Virginia became a royal colony. Charles City Shire was formed in 1634 in the Virginia Colony by order of the King. Its name was changed to Charles City County in 1643. It is one of the five original shires in Virginia that are extant in essentially the same political entity (county) as they were originally formed in 1634. Colonists developed the land as tobacco plantations and produced this commodity crop for export.

Cultivation and processing of this crop required intensive labor. The wealthier planters recruited indentured servants from the British Isles and Africa, and later purchased numerous enslaved Africans. In Virginia and the Upper South, historians have classified persons holding 20 or more slaves as planters.

The original central city of the county was Charles City Point, located south of the James River at the confluence of the Appomattox River. The first Charles City County courthouses were located along the James River at Westover on the north side and at City Point on the south side. The latter's name was shortened from Charles City Point.

Breaking off other counties

In 1634, Charles City Shire became one of the eight original Shires of Virginia established by the British in the Virginia Colony.[5] Since then, five counties: Prince George County, Brunswick, Dinwiddie, Amelia, and Prince Edward; and three independent cities: Hopewell, Petersburg and ; have been formed from the original territory of Charles City Shire.[6] The most significant division was the organization of Prince George County in 1703, which took in all the land south of the James River formerly assigned to Charles City County. The later divisions of Prince George County yielded most of those other counties and independent cities.[7] Charles City County was one of the original Virginia shires of 1634. As the population increased, several other counties were formed from this territory. Beginning in 1703, all of the original area of Charles City County south of the James River was severed to form Prince George. This in turn was later divided, in a pattern typical of colonial development, into several other counties. The incorporated town of City Point, then in Prince George County, was annexed by the independent city of Hopewell in 1923. Prince George County was later divided: Brunswick County was organized in 1732; Amelia County in 1735; and Prince Edward County in 1754, all from territory at one time within the very large Charles City County.

After 1703, Charles City County was limited to land on the north bank of the James River, between James City County (another of the original shires) to its east and Henrico County, another original shire, to its west. On the west, Chesterfield County was organized from Henrico in 1749. Charles City County is bordered by New Kent County to its north and Henrico County to its north-west.

North of the river, the area remained Charles City County. During the late 19th century, numerous crossroads communities developed among the plantations to serve the religious, educational and mercantile needs of the citizenry of rural Charles City County. Crossroad communities, such as Adkins Store, Cedar Grove, Binns Hall, Parrish Hill, Ruthville and Wayside, typically included a store, church and school. (Public schools were not established until after the Civil War, when the Reconstruction legislature founded the system.) As in other parts of the Tidewater, common planters and merchants of Charles City County were attracted by the appeal of Methodist and Baptist preachers in the Great Awakening in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Several Methodist and Baptist churches were established in the early 19th century, mostly in the upland areas of the county. The county also had numerous Quaker settlers. The elite planters of the James River plantations tended to remain Anglican; the United States Episcopal Church was founded after the American Revolution.

The county has no "City", or any centralized city or town. Charles City Court House, which has a Charles City postal address, is the focal point of government. The building that served as the courthouse was constructed in the 1730s. Used until 2007, it was one of only five courthouses in America that was in continuous use for judicial purposes since before the Revolutionary War.[8] A new courthouse has since been built.

Indians

The English named the Weyanoke Peninsula after the Weyanoc, Indians whom they encountered in the area. The Weyanoc were gradually displaced by colonial encroachment. They merged with other, larger tribes about the time of Bacon's Rebellion, in which colonists purposefully attacked friendly Indians.

The Chickahominy River, which forms much of the county's eastern and northern borders, is named after another tribe of Algonquian-speaking Indians whom English colonists encountered in this area. Their descendants still inhabit the region. Chickahominy means "coarse-pounded corn people" in their Algonquian language. At the time of the earliest English settlement, the independent Chickahominy people occupied territory surrounded by numerous tribes of the powerful Powhatan Confederacy, but they were not part of it.[9]

The Chickahominy and Eastern Chickahominy tribes are among seven tribes officially recognized by the Commonwealth of Virginia, and, since January 2018, among the six in the state recognized by the federal government. Many of their descendants still live in the county. The Chickahominy are the second-largest Indian tribe in Virginia, with just under one thousand members.[10] The Eastern Chickahominy tribe has about 130 members.

English colonials

The majority of the colonists were English people who arrived as indentured servants and who owed labor. often as much as seven years, to wealthy patrons who had paid for their passage to gain land and laborers. The English government offered land grants to these patrons under a headright system, which was a way to encourage settlement in the colony. During the 17th century, for economic times encouraged many to settle in the North American colonies. Inthe early years, the Chesapeake Bay Colony had many more men than women, but more women entered began emigrating and families were begun.

As the indentured servants worked off their passage. they would be granted land of their own. Some became planters, owning 20 or more slaves, and they chose to settle in the upland section of the county. By then the most successful planter families already controlled the valuable riverfront property. This gave them ready access to the waterways, the transportation system for trade and travel.

African-Americans

With the growth of tobacco as a cash crop, demand for workers increased. Twenty-three African slaves were known to have been brought to Charles City County before 1660.[11] During the late 1600s and early 1700s, African slave labor rapidly supplanted European indentured servants. By the eighteenth century, slaves had become the major source of agricultural labor in the Virginia Colony, then devoted primarily to the labor-intensive commodity crop of tobacco.

The earliest record of a free black living in Charles City County is the September 16, 1677 petition for freedom by a woman named Susannah. The Lott Cary House in the county has long been honored as the birth site of Lott Cary, a slave who purchased his freedom and that of his children.[12] In the 19th century, he became a founding father of the new country of Liberia in Africa.[13]

Beginning as early as the 17th century, some planters freed individual slaves by manumission. Some free mixed-race families, established before the American Revolution, were formed by descendants of unions or marriages between white indentured or free women and African men, indentured, slave or free. Colonial law and the principle of partus sequitur ventrem, provided that children were born into the status of their mother. Thus, the mixed-race children of white women were born free. If illegitimate, they had to serve time in lengthy apprenticeships, but freedom gave them an important step forward.[14]

In the first two decades after the American Revolution, numerous planters in Charles City County freed their slaves, persuaded by Quaker, Baptist and Methodist abolitionists.[15] Many free blacks settled together in today's Ruthville, Virginia, a crossroads and one of the first free-black communities in present-day Charles City County and the state of Virginia.[15] The unincorporated town of Ruthville was the center of the county's free black population for many years. Following emancipation, Ruthville became the site of the Mercantile Cooperative Company and the Ruthville Training School. The United Sorghum Growers Club also met here. Known previously by several other names, the name "Ruthville" recalls local resident Ruth Brown. Her name was selected for the local Post Office established there in 1880.[12]

When the Union Army began recruiting black troops during the American Civil War, many African Americans from Charles City County enlisted. In 1864, United States Colored Troops stationed at Fort Pocahontas roundly repelled an attack by 2500 Confederate troops commanded by Major General Fitzhugh Lee, nephew of General Robert E. Lee.[16] During Reconstruction, freedmen founded several benevolent associations, such as the Odd Fellows Lodge, Knights of Gideon, Order of St. Luke and the Benevolent Society, which were active in resolving common post-emancipation civic issues.

Virginia established statewide legal racial segregation when white Democrats regained control of the state legislature. They disfranchised most blacks at the turn of the century, maintaining this exclusion until after passage of civil rights legislation.

In 1968, following passage of the federal Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act of the 1960s, and federal enforcement of the black franchise, James Bradby of Charles City County was the first African-American Virginian to be elected to the position of County Sheriff.[17]

Geography

| Ruthville, VA[18] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 204 square miles (530 km2), of which 183 square miles (470 km2) is land and 21 square miles (54 km2) (10.5%) is water.[19]

Adjacent counties

- New Kent County – north

- James City – east

- Surry County – southeast

- Prince George County – south

- Chesterfield County – southwest

- Henrico County – west

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 5,588 | — | |

| 1800 | 5,365 | −4.0% | |

| 1810 | 5,186 | −3.3% | |

| 1820 | 5,255 | 1.3% | |

| 1830 | 5,500 | 4.7% | |

| 1840 | 4,774 | −13.2% | |

| 1850 | 5,200 | 8.9% | |

| 1860 | 5,609 | 7.9% | |

| 1870 | 4,975 | −11.3% | |

| 1880 | 5,512 | 10.8% | |

| 1890 | 5,066 | −8.1% | |

| 1900 | 5,040 | −0.5% | |

| 1910 | 5,253 | 4.2% | |

| 1920 | 4,793 | −8.8% | |

| 1930 | 4,881 | 1.8% | |

| 1940 | 4,275 | −12.4% | |

| 1950 | 4,676 | 9.4% | |

| 1960 | 5,492 | 17.5% | |

| 1970 | 6,158 | 12.1% | |

| 1980 | 6,692 | 8.7% | |

| 1990 | 6,282 | −6.1% | |

| 2000 | 6,926 | 10.3% | |

| 2010 | 7,256 | 4.8% | |

| Est. 2018 | 6,941 | −4.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[20] 1790–1960[21] 1900–1990[22] 1990–2000[23] 2010–2012[1] | |||

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 7,256 people living in the county. 48.4% were Black or African American, 40.9% White, 7.1% Native American, 0.3% Asian, Pacific Islader, 0.6% of some other race and 2.6% of two or more races. 1.2% were Hispanic or Latino (of any race).

As of the census[24] of 2000, there were 6,926 people, 2,670 households, and 1,975 families living in the county. The population density was 38 people per square mile (15/km²). There were 2,895 housing units at an average density of 16 per square mile (6/km²). The racial makeup of the county was 54.85% Black or African American, 35.66% White, 7.84% Native American, 0.10% Asian, 0.17% from other races, and 1.37% from two or more races. 0.65% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 2,670 households out of which 27.50% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 53.60% were married couples living together, 15.20% had a female householder with no husband present, and 26.00% were non-families. 22.50% of all households were made up of individuals and 8.40% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.59 and the average family size was 3.02.

In the county, the population was spread out with 22.10% under the age of 18, 7.50% from 18 to 24, 28.90% from 25 to 44, 28.80% from 45 to 64, and 12.60% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 40 years. For every 100 females there were 96.30 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.80 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $42,745, and the median income for a family was $49,361. Males had a median income of $32,402 versus $26,000 for females. The per capita income for the county was $19,182. 10.60% of the population and 8.00% of families were below the poverty line. Out of the total people living in poverty, 13.00% are under the age of 18 and 18.50% are 65 or older.

Government

Board of Supervisors

- District I: Gilbert Smith (I)

- District II: William Coada (Chairman) (I)

- District III: Lewis E. Black, III (I)

Constitutional officers

- Clerk of the Circuit Court: Victoria Cox-Washington (I)

- Commissioner of the Revenue: Denise B. Smith (I)

- Commonwealth's Attorney: Robert H. Tyler (I)

- Sheriff: Alan Jones Sr. (I)

- Treasurer: Mindy Bradby (I)

Charles City County is represented by Democrat Jennifer McClellan in the Virginia Senate, Democrat Lamont Bagby in the Virginia House of Delegates, and Democrat Donald McEachin in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Transportation

Only Henrico County to the west is accessible without a river crossing. State Route 106 crosses the James River on the Benjamin Harrison Memorial Bridge, providing the only direct access to areas south of the river and to Hopewell, the closest city. Three bridges across the Chickahominy River link the county with neighboring James City County and Providence Forge in New Kent County.

James River plantations

Charles City County features some of the larger and older of the extant James River plantations along State Route 5. All are privately owned. Many of the houses and/or grounds are open daily to visitors with various admission fees applicable.[25]

Some James River plantations open to the public, listed from west to east, include Shirley Plantation, Edgewood Plantation and Harrison's Mill, Berkeley Plantation, Westover Plantation, Belle Air Plantation, Piney Grove at Southall's Plantation, North Bend Plantation, and Sherwood Forest Plantation. Plantations not open to the public include Evelynton Plantation, Oak Hill, and Greenway Plantation.

William Henry Harrison, the ninth president of the United States, was born at Berkeley Plantation on Feb. 9, 1773. John Tyler, the tenth president, was born at Greenway Plantation in 1790. He bought the nearby Sherwood Forest Plantation in 1842. Tyler descendants have resided at Sherwood Forest Plantation continuously since then.[26]

Shirley Plantation is the home of the Carter family, descendants of General Robert E. Lee (his mother, Ann Hill Carter) who still live and work the plantation today.[27]

Agriculture

Some Charles City County farms along the James River have been under continuous crop production for more than 400 years, but they remain highly productive. Local farmers have won national contests in bushel per acre grain production. A Charles City farmer has been the National Corn Grower in three years, producing 300+ bushels of corn per acre (18.8 t/ha) in the "no-till non-irrigated" category. Two Charles City farmers have won the National Wheat Growers First Place, producing 140+ bushels per acre (9.4 t/ha) of soft red winter wheat.

Charles City County farmers have also helped develop the leading technology for controlling runoff from grain cultivation. Fully 90% of crop land in Charles City County is in a never-till cropping system. When Hurricane Floyd in 1999 dropped approximately 19 inches (480 mm) of rain in 24 hours on some long-term never-till fields, visual observation showed virtually no erosion. A scientific study conducted in 2000 on one long-term never-till field demonstrated a 99.9% reduction in sediment runoff compared to conventional tillage, and a 95% reduction of runoff of nitrogen and phosphorus. This new technology could become a primary strategy to achieve a healthy Chesapeake Bay.

Education

Charles City County Public Schools employs a staff of approximately 235 persons to meet the needs of approximately 1000 students in its three schools. All schools are technologically advanced with full wireless Internet access in both labs and classrooms. The school system strives to serve the whole child by offering students a broad spectrum of programs that includes core studies, electives gifted education, honors, dual enrollment, Advanced Placement, Army Junior ROTC, comprehensive vocational and technical programs, exceptional education programs, Title I reading, alternative education, pre-kindergarten program, and regional Governor's School program participation.[28]

Politics

Charles City County has favored the Democratic candidate in each of the last fifteen presidential elections, during which the Democratic candidate has consistently received over sixty percent of the vote from the county. It was the only county or independent city in Virginia won by George McGovern during the 1972 election,[29] when in fact, Charles City proved McGovern’s fourth strongest county nationwide.[30]

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 35.9% 1,476 | 60.8% 2,496 | 3.2% 135 |

| 2012 | 33.0% 1,396 | 65.5% 2,772 | 1.5% 64 |

| 2008 | 31.0% 1,288 | 68.3% 2,838 | 0.7% 27 |

| 2004 | 36.5% 1,254 | 62.7% 2,155 | 0.9% 30 |

| 2000 | 33.4% 1,023 | 64.6% 1,981 | 2.0% 62 |

| 1996 | 26.2% 729 | 66.1% 1,842 | 7.8% 216 |

| 1992 | 24.2% 729 | 66.7% 2,010 | 9.1% 275 |

| 1988 | 30.6% 826 | 68.1% 1,839 | 1.3% 35 |

| 1984 | 30.0% 776 | 68.7% 1,776 | 1.2% 32 |

| 1980 | 23.7% 506 | 73.4% 1,564 | 2.8% 61 |

| 1976 | 22.5% 439 | 74.6% 1,455 | 2.9% 57 |

| 1972 | 30.8% 535 | 67.8% 1,177 | 1.3% 23 |

| 1968 | 16.3% 320 | 74.3% 1,457 | 9.4% 183 |

| 1964 | 24.0% 323 | 75.9% 1,023 | 0.1% 2 |

| 1960 | 35.0% 337 | 64.6% 623 | 0.4% 4 |

| 1956 | 72.1% 661 | 19.0% 174 | 8.9% 82 |

| 1952 | 40.2% 342 | 57.9% 492 | 1.9% 16 |

| 1948 | 33.6% 167 | 51.9% 258 | 12.5% 72 |

| 1944 | 29.9% 139 | 70.1% 326 | 0.0% 0 |

| 1940 | 27.9% 92 | 72.1% 238 | 0.0% 0 |

| 1936 | 25.3% 79 | 74.7% 233 | 0.0% 0 |

| 1932 | 25.4% 85 | 73.1% 245 | 1.5% 5 |

| 1928 | 66.3% 207 | 33.7% 105 | 0.0% 0 |

| 1924 | 35.3% 82 | 60.8% 141 | 3.9% 9 |

| 1920 | 40.6% 82 | 58.9% 119 | 0.5% 1 |

| 1916 | 28.9% 57 | 70.6% 139 | 0.5% 1 |

| 1912 | 20.4% 37 | 66.9% 121 | 12.7% 23 |

Communities

There are no incorporated towns in Charles City County, but the following unincorporated communities are located in the county:

Census-designated place

Other unincorporated communities

- Adkins Store

- Barnetts

- Berkeley

- Binns Hall

- Greenway

- Holdcroft

- Kimages

- Montpelier

- Mount Airy

- New Hope

- Old Union

- Roxbury

- Ruthville

- Sandy Point

- Sterling

- Tettington

- Wayside

- Westover

- Wilcox Neck

Notable people

- William Henry Harrison, American president

- John Tyler, American president

- John Tyler, Sr., father of John Tyler

- Alec Seward, blues musician[33]

References

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "Archeological Findings", Charles City County Community Plan Draft, Nov 2008, p. 2-7, accessed 23 February 2009

- "History". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 2016-05-29. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

- Henrico County. "Henrico Becomes a Shire". Henrico.us.

- Henrico Historical Society. "Henrico History". Henricohistoricalsociety.org.

- "Notes on Virginia Counties". Wimfamhistory.net. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "Charles City County" Archived November 24, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, Charles City County Website

- "Chickahominy Information". Ewebtribe.com. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-06-30. Retrieved 2005-10-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Charles City County – Slave Ancestor File". Charlescity.org. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Charles City County Historical Markers. Archived 2017-12-30 at the Wayback Machine

- Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Staff (April 1980). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Lott Cary Birth Site" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-05-12.

- Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans in Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware, 1999–2005 Freeafricanamercians.com

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-05-05. Retrieved 2005-12-16.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), Charles City County Website

- "Front Page". Fortpocahontas.org. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Friend Tells Why Sheriff Bradby Took Own Life. The Afro-American.

- "Virginia Beach City County, VA Weather". Usa.com. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- Joeckel, Jeff (12 September 2005). "James River Plantations: A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary". Cr.nps.gov. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- "James River Plantations: Sherwood Forest Plantation - Between Richmond and Williamsburg". Jamesriverplantations.org. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "James River Plantations: Shirley Plantation - Between Richmond and Williamsburg". Jamesriverplantations.org. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "Charles City County Public Schools – Tradition . Technology . Excellence". Ccps.net. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- "David Leip's Presidential Atlas (Maps for Virginia by election)". Uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- David Leip’s U.S. Election Atlas; 1972 Presidential Election Statistics

- Dave Leip’s U.S. Election Atlas; 1960 Presidential General Election Data Graphs – Virginia by County (and later election years)

- Scammon, Richard M. (compiler); America at the Polls: A Handbook of Presidential Election Statistics 1920–1964; pp. 468, 471, 474, 477, 480 ISBN 0405077114

- Eagle, Bob; LeBlanc, Eric S. (2013). Blues: A Regional Experience. Santa Barbara, California: Praeger. p. 132. ISBN 978-0313344237.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1879 American Cyclopædia article Charles City. |