Formal wear

Formal wear, formal attire or full dress is the traditional Western dress code category applicable for the most formal occasions, such as weddings, christenings, confirmations, funerals, Easter and Christmas traditions, in addition to certain state dinners, audiences, balls, and horse racing events. Formal wear is traditionally divided into formal day and evening wear; implying morning dress (morning coat) before 6 p.m., and white tie (dress coat) after 6 p.m. Generally permitted other alternatives, though, are the most formal versions of ceremonial dresses (including court dresses, diplomatic uniforms and academic dresses), full dress uniforms, religious clothing, national costumes, and most rarely frock coats (which preceded morning coat as default formal day wear 1820s-1920s). In addition, formal wear is often instructed to be worn with official full size orders and medals.

| Part of a series on |

| Western dress codes and corresponding attires |

|---|

|

|

|

Casual (anything not above) |

|

Supplementary alternatives

|

|

Legend: |

The protocol indicating particularly men's traditional formal wear has remained virtually unchanged since the early 20th century. Despite decline following the counterculture of the 1960s, it remains observed in formal settings influenced by Western culture: notably around Europe, the Americas, South Africa, Australia, as well as Japan. For women, although fundamental customs for formal ball gowns (and wedding gowns) likewise apply, changes in fashion have been more dynamic. Traditional formal headgear for men is the top hat, and for women picture hats etc. of a range of interpretations. Shoes for men are dress shoes, dress boots or pumps and for women heeled dress pumps. Other accessories such as gloves for men and opera gloves for women may be worn.

Formal wear being the most formal dress code, it is followed by semi-formal wear, equivalently based around daytime black lounge suit, and evening black tie (dinner suit/tuxedo), and evening gown for women. The male lounge suit and female cocktail dress in turn only comes after this level, traditionally associated with informal attire. Notably, if a level of flexibility is indicated (for example "uniform, morning coat or lounge suit", such as seen to the royal wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle in 2018), the hosts tend to wear the most formal interpretation of that dress code in order to save guests the inconvenience of out-dressing.

Since the most formal versions of national costumes are typically permitted as supplementary alternatives to the uniformity of Western formal dress codes, conversely, since most cultures have at least intuitively applied some equivalent level of formality, the versatile framework of Western formal dress codes open to amalgation of international and local customs have influenced its competitiveness as international standard. From these social conventions derive in turn also the variants worn on related occasions of varying solemnity, such as formal political, diplomatic, and academic events, in addition to certain parties including award ceremonies, balls, fraternal orders, high school proms, etc.

History

Clothing norms and fashions fluctuated regionally in the Middle Ages.

More widespread conventions emerged around royal courts in Europe in the more interconnected Early Modern era. The justacorps with cravat, breeches and tricorne hat was established as the first suit (in an anarchaic sense) by the 1660s-1790s. It was sometimes distinguished by day and evening wear.

By the Age of Revolution in the Late Modern era, it was replaced by the previously causal country leisure wear-associated front cutaway dress coat around the 1790s-1810s. At the same time, breeches were gradually replaced by pantaloons, as where tricorne hats by bicorne hats and ultimately by the top hat by the 19th century and henceforth.

By the 1820s, the dress coat was replaced as formal day wear by the dark closed-front knee-length frock coat. However, the dress coat from the transition period was maintained as formal evening wear with white tie, remaining so until this day.

By the 1840s, the first cutaway morning coats of contemporary style emerged, which would eventually replace the frock coat as formal day wear by the 1920s.

Likewise, starting from the 1860s, fashion was further variegated by the gradual introduction of the sportive, shorter suit jacket, likewise originating in the country leisure wear. This evolved into the semi-formal evening wear black tie from the 1880s and the informal wear suit accepted by polite society from the 1920s.

Dress codes

The dress codes counted as formal wear are the formal dress codes of morning dress for daytime and white tie for evenings. Although some consider strollers for daytime and black tie for the evening as formal, they are traditionally considered semi-formal attires, sartorially speaking below in formality level.

The clothes dictated by these dress codes for women are ball gowns. For many uniforms, the official clothing is unisex. Examples of this are court dress, academic dress, and military full dress uniform.

Morning dress

Morning dress is the daytime formal dress code, consisting chiefly for men of a morning coat, waistcoat, and striped trousers, and an appropriate dress for women.

White tie

The required clothing for men, in the evening, is roughly the following:

- Formal trousers, uncuffed, with stripes on leg seams

- White piqué front or plain stiff-fronted shirt with a detachable wing collar, cuff links and shirt studs

- White piqué bow tie

- White piqué vest (waistcoat) or cummerbund[1]

- A (dress coat) tailcoat

- Black patent leather court shoes

- Accessories

Women wear a variety of dresses. See ball gowns, evening gowns, and wedding dresses. Business attire for women has a developmental history of its own and generally looks different from formal dress for social occasions.

Supplementary alternatives

Many invitations to white tie events, like the last published edition of the British Lord Chamberlain's Guide to Dress at Court, explictely state that national costume or national dress may be substituted for white tie.[2][3]

In general, each of the supplementary alternatives applies equally for both day attire, and evening attire.

Ceremonial dress

Including court dresses, diplomatic uniforms, and academic dresses.

Full dress uniform

Prior to World War II formal style of military dress, often referred to as full dress uniform, was generally restricted to the British, British Empire and United States armed forces; although the French, Imperial German, Swedish and other navies had adopted their own versions of mess dress during the late nineteenth century, influenced by the Royal Navy.[4]

In the U.S. Army, evening mess uniform, in either blue or white, is considered the appropriate military uniform for white-tie occasions.[5] The blue mess and white mess uniforms are black tie equivalents, although the Army Service Uniform with bow tie are accepted, especially for non-commissioned officers and newly commissioned officers. For white-tie occasions, of which there are almost none in the United States outside the national capital region for U.S. Army, an officer must wear a wing-collar shirt with white tie and white vest. For black tie occasions, officers must wear a turndown collar with black tie and black cummerbund. The only outer coat prescribed for both black- and white-tie events is the army blue cape with branch color lining.[6]

Religious clothing

Certain clergy wear, in place of white tie outfits, a cassock with ferraiolone, which is a light-weight ankle-length cape intended to be worn indoors. The colour and fabric of the ferraiolone is determined by the rank of the cleric and can be scarlet watered silk, purple silk, black silk or black wool. For outerwear, the black cape (cappa nigra), also known as a choir cape (cappa choralis), is most traditional. It is a long black woolen cloak fastened with a clasp at the neck and often has a hood. Cardinals and bishops may also wear a black plush hat or, less formally, a biretta. In practice, the cassock and especially the ferraiolone have become much less common and no particular formal attire has appeared to replace them. The most formal alternative is a clerical waistcoat incorporating a Roman collar (a rabat) worn with a collarless French cuff shirt and a black suit, although this is closer to black-tie than white tie.

Historically, clerics in the Church of England would wear a knee-length cassock called an apron, accompanied by a tailcoat with silk facings but no lapels, for a white tie occasion. In modern times this is rarely seen. However, if worn, the knee-length cassock is now replaced with normal dress trousers.

First native Catholic parish priest from the Belgian Congo, wearing a Roman cassock with the standard 18 buttons (Gazet van Antwerpen, 2 September 1906)

First native Catholic parish priest from the Belgian Congo, wearing a Roman cassock with the standard 18 buttons (Gazet van Antwerpen, 2 September 1906) Catholic Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone wearing a tropical white cassock trimmed in cardinalatial scarlet in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic (2006)

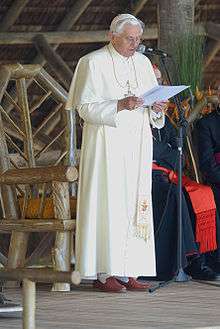

Catholic Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone wearing a tropical white cassock trimmed in cardinalatial scarlet in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic (2006) Pope Benedict XVI in white cassock (sometimes though unofficially called a simar) with pellegrina and fringed white fascia (2007)

Pope Benedict XVI in white cassock (sometimes though unofficially called a simar) with pellegrina and fringed white fascia (2007)- Justin Welby, Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury, and Kim Geun-Sang, Anglican Primate of the Anglican Church of Korea (2013)

- Chief Rabbi Shlomo Amar of Jerusalem, Israel (right) with Jewish scholar Joseph J. Sherman (left) (2014)

Folk costume

In Western formal state ceremonies and social functions, diplomats, foreign dignitaries, and guests of honor wear a Western formal dress if not wearing their own national dress.

Many cultures have a formal day and evening dress, for example:

- Av Pak — both traditional and modern embroidered blouse worn by women in Cambodia at Special occasion, traditional festival and Formal show.

- Bandhgala — also called Jodhpuri suit is worn by men in India is a traditional dress.

- Barong Tagalog — worn by men in the Philippines.

- Bisht — worn by men with thawb and shmagh or ghutrah and agal in formal and religious occasions, e.g. Eid, in some Eastern Arab countries like (Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Kuwait, UAE, Qatar, Bahrain and others).

- Batik shirt — worn by men and women in Indonesia. Besides counting as formal wear, batik shirts are worn well into the informal level.

- Bunad — worn as formal dress by women and men in Norway.

- Changshan — a long male version of the qipao, which originated during the Qing Dynasty. It can be of cotton for ordinary wear, or of silk for those within aristocratic families. Beneath the changshan, the male generally wears a white mandarin-collar long-sleeve shirt and a pair of dark-colored long pants. Like the qipao, this changshan male gown has slits on both sides (at least knee level) as well. Worn nowadays either by Chinese men in the martial arts world or as attire for weddings to match the qipao the bride wears. The qipao and changshan originated as Manchu dresses which government officials, but not ordinary civilians, were required to wear under the Qing Dynasty's laws. Gradually, the general non-official Han Chinese civilian population not voluntarily shifted from wearing traditional Chinese hanfu clothing to the qipao and changshan.

- Cheongsam — a modern female variation of the Qing Dynasty silk dress, characterized by a high mandarin collar, and side open slits of varying lengths. It can be sleeveless, short, elbow or long sleeve, and has been adopted by most Chinese women as Chinese wear, depending on materials and occasions.

- Daura-Suruwal — worn as formal dress by men in Nepal.

- Dashiki — worn by men in West African countries.

- Dhoti — worn by men in Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, the Maldives, and Tamil men in Sri Lanka.

- Folkdräkt — worn as formal dress by women and men in Sweden.

- Hátíðarbúningur — worn by men in Iceland to formal events such as state dinners and weddings.

- Highland dress with Scottish kilt — worn as formal dress by men in Scotland or of Scottish descent

- Kebaya — worn by women in Malaysia and Indonesia.

- Mao suit, worn as diplomatic uniform and evening dress by officials of the People's Republic of China

- Sari — worn by women in India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

- Shalwar kameez — worn by both men and women in Pakistan, India and Bangladesh.

- Sherwani worn by men in India and Pakistan

An Icelandic man wears the hátíðarbúningur formal dress on his wedding day along with a boutonnière.

An Icelandic man wears the hátíðarbúningur formal dress on his wedding day along with a boutonnière.

King Abdullah in Arab formal dress

King Abdullah in Arab formal dress.jpg)

Frock coat

Although ceased as a protocol-regulated required formal attire at the British royal court in 1936 at the order of the short-reigning King Edward VIII, the frock coat - embodying the background for all contemporary civil formal wear - has not altogether vanished. Yet, it is a rarity mostly confined to infrequent appearances at certain weddings.

The state funeral of Winston Churchill in 1965 included bearers of frock coats.[7]

To this day, King Tupou VI of Tonga (born 1959) has been a frequent wearer of frock coats at formal occasions.

Also more recent fashion has been inspired by frock coats: Prada's autumn editions of 2012,[8] Alexander McQueen's menswear in the autumn of 2017,[9] and Paul Smith's autumn 2018.[10]

Gallery

Morning dress

Morning dress in 1901

Morning dress in 1901 Sir John Goodwin and Lady Goodwin together with Neil Campbell and his wife, walking over the Grey Street Bridge in morning dress, top hats and spats (1931)

Sir John Goodwin and Lady Goodwin together with Neil Campbell and his wife, walking over the Grey Street Bridge in morning dress, top hats and spats (1931) Torsten Nothin, Gunnar Asplund, Crown Prince Gustav Adolf, Prince Eugen and Yngve Larsson at the inauguration of Skogskyrkogården, Stockholm, Sweden (1940)

Torsten Nothin, Gunnar Asplund, Crown Prince Gustav Adolf, Prince Eugen and Yngve Larsson at the inauguration of Skogskyrkogården, Stockholm, Sweden (1940) Former U.S. President Harry Truman with William Lyon Mackenzie King (1947)

Former U.S. President Harry Truman with William Lyon Mackenzie King (1947) Men in morning dress and women in wedding gowns at a wedding (1929)

Men in morning dress and women in wedding gowns at a wedding (1929) John F. Kennedy and Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, in morning dress and wedding gown, outdoors (1953)

John F. Kennedy and Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, in morning dress and wedding gown, outdoors (1953)

White tie

- Caricature of William Lygon, 7th Earl Beauchamp in Vanity Fair (1899)

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in evening white tie formal wear (1925)

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in evening white tie formal wear (1925) Queen Elizabeth II (in ball gown) and Prince Philip (full dress uniform) before the formal (full dress) opening of the Parliament of Canada (1957), surrounded by participators of varying degrees of formal attire (morning dress, white tie etc.), presumably in accordance with their functions or time of arrival and departure

Queen Elizabeth II (in ball gown) and Prince Philip (full dress uniform) before the formal (full dress) opening of the Parliament of Canada (1957), surrounded by participators of varying degrees of formal attire (morning dress, white tie etc.), presumably in accordance with their functions or time of arrival and departure President of the United States Gerald Ford, First Lady Betty Ford, Japanese Emperor Hirohito and Empress Nagako (the men in white tie) during a state dinner (1975)

President of the United States Gerald Ford, First Lady Betty Ford, Japanese Emperor Hirohito and Empress Nagako (the men in white tie) during a state dinner (1975) King Willem-Alexander and Queen Maxima walking to the Nieuwe Kerk on his inauguration day (30 April 2013)

King Willem-Alexander and Queen Maxima walking to the Nieuwe Kerk on his inauguration day (30 April 2013)

See also

References

- https://www.gentlemansgazette.com/tuxedo-black-tie-guide/vintage-evening-wear/waistcoats-vests-cummerbunds/

- Canadian Heritage (1985). "Dress". "Diplomatic and Consular Relations and Protocol" External Affairs. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- Nobleprize.org. "The Dress Code at the Nobel Banquet: What to wear?".

- Knötel, Knötel & Sieg (1980), pp. 442–445.

- http://www.ncoguide.com/files/da-pam-670_1.pdf

- http://www.ncoguide.com/files/da-pam-670_1.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hQldUeevrQQ

- https://www.vogue.co.uk/shows/autumn-winter-2012-menswear/prada/collection

- https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/frock-coat/

- https://www.vogue.com/fashion-shows/fall-2018-menswear/paul-smith/slideshow/collection