Veil

A veil is an article of clothing or hanging cloth that is intended to cover some part of the head or face, or an object of some significance. Veiling has a long history in European, Asian, and African societies. The practice has been prominent in different forms in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The practice of veiling is especially associated with women and sacred objects, though in some cultures it is men rather than women who are expected to wear a veil. Besides its enduring religious significance, veiling continues to play a role in some modern secular contexts, such as wedding customs.

History

Antiquity

Elite women in ancient Mesopotamia and in the Greek and Persian empires wore the veil as a sign of respectability and high status.[1] The earliest attested reference to veiling is found a Middle Assyrian law code dating from between 1400 and 1100 BC.[2] Assyria had explicit sumptuary laws detailing which women must veil and which women must not, depending upon the woman's class, rank, and occupation in society.[1] Female slaves and prostitutes were forbidden to veil and faced harsh penalties if they did so.[3] The Middle Assyrian law code states:

§ 40. A wife-of-a-man, or [widows], or [Assyrian] women who go out into the main thoroughfare [shall not have] their heads [bare]. [...] A prostitute shall not veil herself, her head shall be bare. Whoever sees a veiled prostitute shall seize her, secure witnesses, and bring her to the palace entrance. They shall not take her jewelry; he who has seized her shall take her clothing; they shall strike her 50 blows with rods; they shall pour hot pitch over her head. And if a man should see a veiled prostitute and release her and not bring her to the palace entrance: they shall strike that man 50 blows with rods; the one who informs against him shall take his clothing; they shall pierce his ears, thread (them) on a cord, tie (it) at his back; he shall perform the king’s service for one full month. Slave-women shall not veil themselves, and he who should see a veiled slave-woman shall seize her and bring her to the palace entrance: they shall cut off her ears; he who seizes her shall take her clothing.[4]

Veiling was thus not only a marker of aristocratic rank, but also served to "differentiate between 'respectable' women and those who were publicly available".[1][3] The veiling of matrons was also customary in ancient Greece. Between 550 and 323 B.C.E respectable women in classical Greek society were expected to seclude themselves and wear clothing that concealed them from the eyes of strange men.[5]

The Mycenaean Greek term 𐀀𐀢𐀒𐀺𐀒, a-pu-ko-wo-ko, possibly meaning "headband makers" or "craftsmen of horse veil", and written in Linear B syllabic script, is also attested since ca. 1300 BC.[6][7] In ancient Greek the word for veil was καλύπτρα (kalyptra; Ionic Greek: καλύπτρη, kalyptrē; from the verb καλύπτω, kalyptō, "I cover").[8]

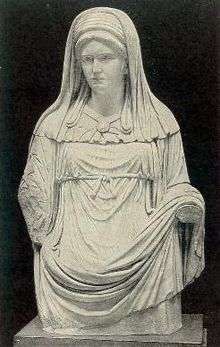

Classical Greek and Hellenistic statues sometimes depict Greek women with both their head and face covered by a veil. Caroline Galt and Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones have both argued from such representations and literary references that it was commonplace for women (at least those of higher status) in ancient Greece to cover their hair and face in public. Roman women were expected to wear veils as a symbol of the husband's authority over his wife; a married woman who omitted the veil was seen as withdrawing herself from marriage. In 166 BC, consul Sulpicius Gallus divorced his wife because she had left the house unveiled, thus allowing all to see, as he said, what only he should see. Unmarried girls normally didn't veil their heads, but matrons did so to show their modesty and chastity, their pudicitia. Veils also protected women against the evil eye, it was thought.[9]

A veil called flammeum was the most prominent feature of the costume worn by the bride at Roman weddings.[10] The veil was a deep yellow color reminiscent of a candle flame. The flammeum also evoked the veil of the Flaminica Dialis, the Roman priestess who could not divorce her husband, the high priest of Jupiter, and thus was seen as a good omen for lifelong fidelity to one man. The Romans apparently thought of the bride as being "clouded over with a veil" and connected the verb nubere (to be married) with nubes, the word for cloud.[11]

Intermixing of populations resulted in a convergence of the cultural practices of Greek, Persian, and Mesopotamian empires and the Semitic peoples of the Middle East.[3] Veiling and seclusion of women appear to have established themselves among Jews and Christians, before spreading to urban Arabs of the upper classes and eventually among the urban masses.[3] In the rural areas it was common to cover the hair, but not the face.[3]

Later history

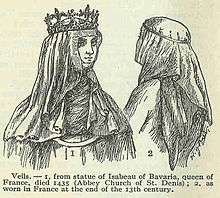

For many centuries, until around 1175, Anglo-Saxon and then Anglo-Norman women, with the exception of young unmarried girls, wore veils that entirely covered their hair, and often their necks up to their chins (see wimple). Only in the Tudor period (1485), when hoods became increasingly popular, did veils of this type become less common. This varied greatly from one country to another. In Italy, veils, including face veils, were worn in some regions until the 1970s.[12] Women in southern Italy often covered their heads to show that they were modest, well-behaved and pious. They generally wore a cuffia (cap), then the fazzoletto (kerchief/head scarves) a long triangular or rectangular piece of cloth that could be tied in various way, and sometimes covered the whole face except the eyes, sometimes bende (lit. swaddles, bandages) or a wimple underneath too.[13]

For centuries, European women have worn sheer veils, but only under certain circumstances. Sometimes a veil of this type was draped over and pinned to the bonnet or hat of a woman in mourning, especially at the funeral and during the subsequent period of "high mourning". They would also have been used, as an alternative to a mask, as a simple method of hiding the identity of a woman who was traveling to meet a lover, or doing anything she didn't want other people to find out about. More pragmatically, veils were also sometimes worn to protect the complexion from sun and wind damage (when un-tanned skin was fashionable), or to keep dust out of a woman's face, much as the keffiyeh(worn by men) is used today.

_-_TIMEA.jpg)

In Judaism, Christianity, and Islam the concept of covering the head is or was associated with propriety and modesty. Most traditional depictions of the Virgin Mary, the mother of Christ, show her veiled. During the Middle Ages most European married women covered their hair rather than their face, with a variety of styles of wimple, kerchiefs and headscarves. Veiling, covering the hair, rather than the face, was a common practice with church-going women until the 1960s, Catholic women typically using lace, and a number of very traditional churches retain the custom. Bonnets were the rule in non-Catholic churches. Lace face-veils are still often worn by female relatives at funerals in some Catholic countries. In Orthodox Judaism, married women cover their hair for reasons of modesty; many Orthodox Jewish women wear headscarves (tichel) for this purpose.

Christian Byzantine literature expressed rigid norms pertaining to veiling of women, which have been influenced by Persian traditions, although there is evidence to suggest that they differed significantly from actual practice.[5] Since Islam identified with the monotheistic religions practiced in the Byzantine and Sassanian empires, in the aftermath of the early Muslim conquests veiling of women was adopted as an appropriate expression of Qur'anic ideals regarding modesty and piety.[14] Veiling gradually spread to upper-class Arab women, and eventually, it became widespread among Muslim women in cities throughout the Middle East. Veiling of Arab Muslim women became especially pervasive under Ottoman rule as a mark of rank and exclusive lifestyle, and Istanbul of the 17th century witnessed differentiated dress styles that reflected geographical and occupational identities.[3] Women in rural areas were much slower to adopt veiling because the garments interfered with their work in the fields.[15] Since wearing a veil was impractical for working women, "a veiled woman silently announced that her husband was rich enough to keep her idle."[16] By the 19th century, upper-class urban Muslim and Christian women in Egypt wore a garment which included a head cover and a burqa (muslin cloth that covered the lower nose and the mouth).[3] Up to the first half of the twentieth century, rural women in the Maghreb and Egypt put on a face veil when they visited urban areas, "as a sign of civilization".[17] The practice of veiling gradually declined in much of the Muslim world during the 20th century before making a comeback in recent decades The choice, or the forced option for women to veil remains controversial, whether a personal choice as an outward sign of religious devotion, or a forced one because of extremist groups that require a veil, under severe penalty, even death. [18] The motives and reasons for wearing a hijab are wide and various, but ultimately depend on each individual person's situation and can not be said to come from any one distinct reason or motive. [19] Although religion can be a common reason for choosing to veil, the practice also reflects political and personal conviction, so that it can serve as a medium through which personal choices can be revealed, in countries where veiling is indeed a choice, such as Turkey.[20]

Veils for men

Among the Tuareg, Songhai, Hausa, and Fulani of West Africa, women do not traditionally wear the veil, while men do. Male veiling was also common among the Berber Sanhaja tribes.[21] The North African male veil, which covers the mouth and sometimes part of the nose, is called litham in Arabic and tagelmust by the Tuareg.[21][22] Tuareg boys start wearing the veil at the onset of puberty and veiling is regarded as a mark of manhood.[22] It is considered improper for a man to appear unveiled in front of elders, especially those from his wife's family.[22]

Ancient African rock engravings depicting human faces with eyes but no mouth or nose suggest that the origins of litham are not only pre-Islamic but even pre-historic.[21] Wearing of the litham is not viewed as a religious requirement, although it was apparently believed to provide magical protection against evil forces.[21] In practice, the litham has served as protection from the dust and extremes of temperature characterizing the desert environment.[21] Its use by the Almoravids gave it a political significance during their conquests.[21]

In some parts of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Nepal, men wear a sehra on their wedding day. This is a male veil covering the whole face and neck. The sehra is made from either flowers, beads, tinsel, dry leaves, or coconuts. The most common sehra is made from fresh marigolds. The groom wears this throughout the day concealing his face even during the wedding ceremony. In Northern India today you can see the groom arriving on a horse with the sehra wrapped around his head.

Veiling and religion

Biblical references

Biblical references include:

- Hebrew mitpachat (Ruth 3:15[23]; marg., "sheet" or "apron;" R.V., "mantle"). In Isaiah 3:22[24] this word is plural, rendered "wimples;" R.V., "shawls" i.e. wraps.

- Massekah (Isaiah 25:7[25]; in Isaiah 28:20[26] rendered "covering"). The word denotes something spread out and covering or concealing something else (compare with 2 Corinthians 3:13–15[27]).

- Masveh (Exodus 34:33, 35[28]), the veil on the face of Moses. This verse should be read, "And when Moses had done speaking with them, he put a veil on his face," as in the Revised Version. When Moses spoke to them he was without the veil; only when he ceased speaking he put on the veil (compare with 2 Corinthians 3:13[29]).

- Parochet (Exodus 26:31–35[30]), the veil of the tabernacle and the temple, which hung between the holy place and the most holy (2 Chronicles 3:14[31]). In the temple, a partition wall separated these two places. In it were two folding doors, which are supposed to have been always open, the entrance being concealed by the veil which the high priest lifted when he entered into the sanctuary on the Day of Atonement. This veil was rent when Christ died on the cross (Matthew 27:51[32]; Mark 15:38[33]; Luke 23:45[34]).

- Tza'iph (Genesis 24:65[35]). Rebecca "took a veil and covered herself." (See also Genesis 38:14,19[36]) Hebrew women generally appeared in public with the face visible (Genesis 12:14[37]; 24:16; 29:10; 1 Samuel 1:12[38]).

- Radhidh (Song of Solomon 5:7[39], R.V. "mantle;" Isaiah 3:23[40]). The word probably denotes some kind of cloak or wrapper.

- Masak, the veil which hung before the entrance to the holy place (Exodus 26:36–37[41]).

Note: Genesis 20:16[42], which the King James Version renders as: "And unto Sarah he said, Behold, I have given thy brother a thousand pieces of silver: behold, he is to thee a covering of the eyes, unto all that are with thee, and with all other: thus she was reproved" has been interpreted in one source as implied advice to Sarah to conform to a supposed custom of married women, and wear a complete veil, covering the eyes as well as the rest of the face,[43] but the phrase is generally taken to refer not to Sarah's eyes, but to the eyes of others, and to be merely a metaphorical expression concerning vindication of Sarah (NASB, RSV), silencing criticism (GWT), allaying suspicions (NJB), righting a wrong (BBE, NLT), covering or recompensing the problem caused her (NIV, New Life Version, NIRV, TNIV, JB), a sign of her innocence (ESV, CEV, HCSB). The final phrase in the verse, which KJV takes to mean "she was reproved", is taken by almost all other versions to mean instead "she was vindicated", and the word "הוא", which KJV interprets as "he" (Abraham), is interpreted as "it" (the money). Thus, the general view is that this passage has nothing to do with material veils.

Judaism

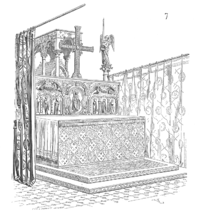

After the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, the synagogues that were established took the design of the Tabernacle as their plan.[44] The Ark of the Law, which contains the scrolls of the Torah, is covered with an embroidered curtain or veil called a parokhet. (See also below regarding the traditional Jewish custom of veiling – and unveiling – the bride.)

Christianity

Veiling of objects

Among Christian churches which have a liturgical tradition, several different types of veils are used. These veils are often symbolically tied to the veils in the Tabernacle in the wilderness and in Solomon's Temple. The purpose of these veils was not so much to obscure as to shield the most sacred things from the eyes of sinful men. In Solomon's Temple the veil was placed between the "Inner Sanctuary" and the "Holy of Holies". According to the New Testament, this veil was torn when Jesus Christ died on the cross.

- Tabernacle veil

- Used to cover the church tabernacle, particularly in the Roman Catholic tradition but in some others as well, when the Eucharist is actually stored in it.[44] The veil is used to remind worshipers that the (usually metal) tabernacle cabinet echoes the tabernacle tent of the Hebrew Scriptures, and it signals that the tabernacle is actually in use.[44] It may be of any liturgical color, but is most often white (always appropriate for the Eucharist), cloth of gold or silver (which may substitute for any liturgical color aside from violet), or the liturgical color of the day (red, green or violet). It may be simple, unadorned linen or silk, or it may be fringed or otherwise decorated. It is often designed to match the vestments of the celebrants.

- Ciborium veil

- The ciborium is a goblet-like metal vessel with a cover, used in the Roman Catholic Church and some others to hold the consecrated hosts of the Eucharist when, for instance, it is stored in the tabernacle or when communion is to be distributed. It may be veiled with a white cloth, usually silk. This veiling was formerly required but is now optional. In part, it signals that the ciborium actually contains the consecrated Eucharist at the moment.

- Chalice veil

- During Eucharistic celebrations, a veil is often used to cover the chalice and paten to keep dust and flying insects away from the bread and wine. Often made of rich material, the chalice veils have not only a practical purpose, but are also intended to show honor to vessels used for the sacrament.

- In the West, a single chalice veil is normally used. The veil will usually be the same material and color as the priest's vestments, though it may also be white. It covers the chalice and paten when not actually in use on the altar.

- In the East, three veils are used: one for the chalice, one for the diskos (paten), and a third one (the Aër) is used to cover both. The veils for the chalice and diskos are usually square with four lappets hanging down the sides, so that when the veil is laid out flat it will be shaped like a cross. The Aër is rectangular and usually larger than the chalice veil used in the West. The Aër also figures prominently in other liturgical respects.

- Humeral veil

- The humeral veil is used in both Roman Catholic and Anglican Churches during the liturgy of Exposition and Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament, and on some other occasions when special respect is shown to the Eucharist. From the Latin for "shoulders," it is an oblong piece of cloth worn as a sort of shawl, used to symbolize a more profound awareness of the respect due to the Eucharist by shielding the celebrant's hands from actually contacting the vessel holding the Eucharist, either a monstrance or ciborium, or in some cases to shield the vessel itself from the eyes of participants. It is worn only by bishops, priests or deacons.

- Vimpa

- A vimpa is a veil or shawl worn over the shoulders of servers who carry the miter and crosier in Roman Catholic liturgical functions when they are not being used by the bishop.

- Chancel veil

- In the early liturgies, there was often a veil that separated the sanctuary from the rest of the church (again, based upon the biblical description of the Tabernacle). In the Byzantine liturgy this veil developed into the iconostasis, but a veil or curtain is still used behind the Royal Doors (the main doors leading into the sanctuary), and is opened and closed at specific times during the liturgy. In the West, it developed into the Rood Veil, and later the Rood Screen, and finally the chancel rail, the low sanctuary railing in those churches that still have this. In some of the Eastern Churches (for instance, the Syrian liturgy) the use of a veil across the entire sanctuary has been retained.

- Lenten veiling

- Some churches veil their crosses during Passiontide with a fine semi-transparent mesh. The color of the veil may be black, red, purple, or white, depending upon the liturgical day and practice of the church. In traditional churches, there will sometimes be curtains placed to either side of the altar.

The Veil of our Lady is a liturgical feast celebrating the protection afforded by the intercessions of the Virgin Mary.

Veiling by women

Traditionally, in Christianity, women were enjoined to cover their heads in church, just as it was (and still is) customary for men to remove their hat as a sign of respect. Wearing a veil (also known as a headcovering) is seen as a sign of humility before God, as well as a reminder of the bridal relationship between Christ and the church.[44][46][47] This practice is based on 1 Corinthians 11:4–16 in the Christian Bible, where St. Paul writes:[48]

Now I praise you, brethren, that ye remember me in all things, and keep the ordinances, as I delivered them to you. But I would have you know, that the head of every man is Christ; and the head of the woman is the man; and the head of Christ is God. Every man praying or prophesying, having his head covered, dishonoureth his head. But every woman that prayeth or prophesieth with her head uncovered dishonoureth her head: for that is even all one as if she were shaven. For if the woman be not covered, let her also be shorn: but if it be a shame for a woman to be shorn or shaven, let her be covered. For a man indeed ought not to cover his head, forasmuch as he is the image and glory of God: but the woman is the glory of the man. For the man is not of the woman: but the woman of the man. Neither was the man created for the woman; but the woman for the man. For this cause ought the woman to have power on her head because of the angels. Nevertheless neither is the man without the woman, neither the woman without the man, in the Lord. For as the woman is of the man, even so is the man also by the woman; but all things of God. Judge in yourselves: is it comely that a woman pray unto God uncovered? Doth not even nature itself teach you, that, if a man have long hair, it is a shame unto him? But if a woman have long hair, it is a glory to her: for her hair is given her for a covering. But if any man seem to be contentious, we have no such custom, neither the churches of God.

In Western Europe and North America at the start of the 20th century, women in most mainstream Christian denominations wore head coverings during church services (often in the form of a scarf, cap, veil or hat).[49] These included many Anglican,[50] Baptist,[51] Catholic,[52][53] Lutheran,[54] Methodist,[55] Presbyterian Churches.[56][57][58] In these denominations, the practice now continues in isolated parishes where it is seen as a matter of etiquette, courtesy, tradition or fashionable elegance.[52]

Christian veiling is still practiced, especially among those who wear plain dress, such as Conservative Quakers and many Anabaptists (including Mennonites, Hutterites,[59] Old German Baptist Brethren,[60] Apostolic Christians and Amish). Moravian females wear a lace headcovering called a haube, especially when serving as dieners.[61] Many Holiness Christians who practice the doctrine of outward holiness, also practice headcovering,[62] in addition to the Laestadian Lutheran Church, the Plymouth Brethren, and the more conservative Scottish and Irish Presbyterian and Dutch Reformed churches. Traditionalist Catholics still follow it, generally as a matter of custom and biblically approved aptness; some also suppose that St. Paul's directive is in full force today as an ordinance of its own right, despite the teaching of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith's pronouncement on the matter, which stated that practice of headcovering for women was a matter of ecclesiastical discipline and not of Divine law;[52]

In many traditional Eastern Orthodox Churches, and in some conservative Protestant churches as well, the custom continues of women covering their heads in church (or even when praying privately at home).

Veiling by nuns

A veil over the hair rather than the face forms part of the headdress of some orders of nuns or religious sisters; this is why a woman who becomes a nun is said "to take the veil". In medieval times married women normally covered their hair outside the house, and a nun's veil is based on secular medieval styles, often reflecting the fashion of widows in their attire. In many institutes, a white veil is used as the "veil of probation" during novitiate, and a dark veil for the "veil of profession" once religious vows are taken; the color scheme varies with the color scheme of the habit of the order. A veil of consecration, longer and fuller, is used by some orders for final profession of solemn vows.

Nuns are the female counterparts of monks, and many monastic orders of women have retained the veil. Regarding other institutes of religious sisters who are not cloistered but who work as teachers, nurses or in other "active" apostolates outside of a nunnery or monastery, some wear the veil, while some others have abolished the use of the veil, and a few never had a veil to start with, but used a bonnet-style headdress as in the case of St. Elizabeth Ann Seton.

The fullest versions of the nun's veil cover the top of the head and flow down around and over the shoulders. In western Christianity, it does not wrap around the neck or face. In those orders that retain one, the starched white covering about the face, neck, and shoulders is known as a wimple and is a separate garment.

The Catholic Church has revived the ancient practice of allowing women to be consecrated by their bishop as a consecrated virgin. These women are set aside as sacred persons who belong only to Christ and the service of the church. The veil is a bridal one, because the velatio virginum primarily signified the newly consecrated virgin as the Bride of Christ. At one point this veil was called the flammeum because it was supposed to remind the virgin of the indissoluble nuptial bond she was contracting with Christ. The wearing of the flammeum for the sacred virgin Bride of Christ arose from the bridal attire of the strictest pagan marriage which did not permit of divorce at the time. The flammeum was a visible reminder that divorce was not possible with Christ, their Divine Spouse. Consecrated virgins are under the direct care of the local bishop, without belonging to a particular order, and they receive the veil as a bridal sign of consecration.

There has also been renewed interest in the last half century in the ancient practice of women and men dedicating themselves as anchorites or hermits, and there is a formal process whereby such persons can seek recognition of their vows by the local bishop; a veil for these women would be traditional.

Some Lutheran and Anglican women's religious orders also wear a veil, differing according to the traditions of each order.

In Eastern Orthodoxy and in the Eastern Rites of the Catholic Church, a veil called an epanokamelavkion is used by both nuns and monks, in both cases covering completely the kamilavkion, a cylindrical hat they both wear. In Slavic practice, when the veil is worn over the hat, the entire headdress is referred to as a klobuk. Nuns wear an additional veil under the klobuk, called an apostolnik, which is drawn together to cover the neck and shoulders as well as the head, leaving the face itself open.

Islam

A variety of headdresses worn by Muslim women and girls in accordance with hijab (the principle of dressing modestly) are sometimes referred to as veils. The principal aim of the Muslim veil is to cover the Awrah (parts of the body that are considered private). Many of these garments cover the hair, ears and throat, but do not cover the face.

Depending on geography and culture, the veil is referenced and worn in different ways. The khimar is a type of headscarf. The niqāb and burqa are two kinds of veils that cover most of the face except for a slit or hole for the eyes. In Algeria, a larger veil called the haïk includes a triangular panel to cover the lower part of the face.[63] In the Arabian Peninsula and parts of North Africa (specifically Saudi Arabia), the abaya is worn constructed like a loose robe covering everything but the face itself. In another location, such as Iran, the chador is worn as the semicircles of fabric are draped over the head like a shawl and held in place under the neck by hand. The two terms for veiling that are directly mentioned in the Quran is the jilbab and the khimar. In these references, the veiling is meant to promote modesty by covering the genitals and breasts of women.

The Afghan burqa covers the entire body, obscuring the face completely, except for a grille or netting over the eyes to allow the wearer to see. The boshiya is a veil that may be worn over a headscarf; it covers the entire face and is made of a sheer fabric so the wearer is able to see through it. It has been suggested that the practice of wearing a veil – uncommon among the Arab tribes prior to the rise of Islam – originated in the Byzantine Empire, and then spread.[64]

In Central Asian sedentary Muslim areas (today Uzbekistan and Tajikistan) women wore veils which when worn the entire face was shrouded, called Paranja[65] or faranji. The traditional veil in Central Asia worn before modern times was the faranji[66] but it was banned by the Soviet Communists.[67][68]

Restrictions

The wearing of head and especially face coverings by Muslim women has raised political issues in the West; including in Quebec, and across Europe. Countries and territories that have banned or partially banned the veil include, among others:

- France, where full-face veils (burqa and niqab) have been banned in public places since April 2011, with a 150-euro fine for breaching the ban. All religious veils have been banned in public schools.

- Belgium, also banned full face veils in public places, in July 2011.

- Spain has several towns and cities which have banned the full face veil, including Barcelona.

- Russia's Stavropol region has announced a ban on hijabs in government schools, which was challenged but upheld by the Russian Supreme Court.[69][70]

Places where headscarves continue to be a contentious political issue include:

- United Kingdom, where the Home Office Minister Jeremy Browne called for a national debate about headscarves and their role in public environments in Britain.[70]

- Quebec, where there is much discussion as to whether the province should allow people wearing a veil over their face to vote without removing it.

- Europe, with a large Muslim population, the EU has allowed countries to ban full-face veils, as it does not breach the European Convention on Human Rights.[71]

Indian religions

In Indian subcontinent, from 1st century B.C. societies advocated the use of the veil for married Hindu women which came to be known as Ghoonghat.[72] Buddhists attempted to counter this growing practice around 3rd century CE.[73] Rational opposition against veiling and seclusion from spirited ladies resulted in system not becoming popular for several centuries.[72] Under the Medieval Islamic Mughal Empire, various aspects of veiling and seclusion of women was adopted, such as the concept of Purdah and Zenana, partly as an additional protection for women.[72] Purdah became common in the 15th and 16th century, as both Vidyāpati and Chaitanya mention it.[72] Sikhism was highly critical of all forms of strict veiling, Guru Amar Das condemned it and rejected seclusion and veiling of women, which saw decline of veiling among some classes during late medieval period.[74] This was stressed by Bhagat Kabir.[75]

Stay, stay, O daughter-in-law - do not cover your face with a veil. In the end, this shall not bring you even half a shell. The one before you used to veil her face; do not follow in her footsteps. The only merit in veiling your face is that for a few days, people will say, "What a noble bride has come". Your veil shall be true only if you skip, dance and sing the Glorious Praises of the Lord. Says Kabeer, the soul-bride shall win, only if she passes her life singing the Lord's Praises.

— Bhagat Kabir, Guru Granth Sahib 484 [75]

Bridal veils

The veil is one of the oldest parts of a bridal ensemble, dating as far back as Greek and Roman times, to hide a bride "from evil spirits who might want to thwart her happiness" or to frighten the spirits away.[10][76][77][78][79] The veil also served to hide the bride's face from the groom prior to the wedding, as superstition says that it is bad luck for the groom to see the bride before the ceremony.[77][79] As weddings became more religious ceremonies in Western culture, the veil was used to symbolize modesty before God, obedience, and when the veil was white, chastity.[76][77][79][80][81][82] By the 17th and 18th century, bridal veils were occasionally worn, but were generally out of fashion in Britain and North America, with brides choosing from many other options instead.[76][83] However, the bridal veil returned to popularity after Queen Victoria wore a veil in her wedding to Prince Albert in 1840.[76] The bridal veil became a status symbol during the Victorian era, and the weight, length, and quality of the veil indicated the bride's social status.[10] Bridal veils worn over the face were not common until the second half of the 19th century.[83]

The tradition of a veiled bride's face continues today wherein, a virgin bride, especially in Christian or Jewish culture, enters the marriage ritual with a veiled face and head, and remains fully veiled, both head and face, until the ceremony concludes. After the full conclusion of the wedding ceremony, either the bride's father lifts the veil, presenting the bride to the groom who then kisses her, or the new groom lifts her face veil in order to kiss her.[78][84] Some see the lifting of the veil as symbolically consummating the marriage, representing another thin membrane (the hymen) that will be physically penetrated on the wedding night.[79][85]

In modern weddings, the lifting of the veil at the conclusion of the ceremony to present the bride to the groom may not occur, since it may be considered sexist for the bride to have her face covered through the ceremony, whether or not the veil is worn to symbolize virginity.[79] Often the veil is worn solely as a fashion accessory as part of the bridal attire, instead of for its symbolism.[10][79] A bridal veil is not normally worn during a civil marriage ceremony, nor when the bride is remarrying.

In Scandinavia, the bridal veil is usually worn under a traditional crown and does not cover the bride’s face; instead, the veil is attached to and hangs from the back.[86]

Judaism

In Judaism, the tradition of the bride wearing a veil during the wedding ceremony dates back to biblical times. According to the Torah in Genesis 24:65, Isaac is brought Rebekah to marry by his father Abraham's servant, and Rebekah took her veil and covered herself when Isaac was approaching.[87]

In a traditional Jewish wedding, just before the ceremony, the badeken takes place, at which the groom places the veil over the bride's face, and either he or the officiating rabbi gives her a blessing.[79][87] The veil stays on her face until just before the end of the wedding ceremony – when they are legally married according to Jewish law – then the groom helps lift the veil off her face. The most often cited interpretation for the badeken is that, according to Genesis 29, when Jacob went to marry Rachel, his father-in-law Laban tricked him into marrying Leah, Rachel's older and homelier sister.

Many say that the veiling ceremony takes place to make sure that the groom is marrying the right bride. Some say that as the groom places the veil over his bride, he makes an implicit promise to clothe and protect her. Finally, by covering her face, the groom recognizes that he is marrying the bride for her inner beauty; while looks will fade with time, his love will be everlasting.[87] In some ultra-orthodox communities, it is a custom for the bride to wear an opaque veil as she is escorted to the groom. This is said to show her complete willingness to enter into the marriage and her absolute trust that she is marrying the right man.

In ancient Judaism, the lifting of the veil took place just prior to the consummation of the marriage in sexual union. The uncovering or unveiling that takes place in the wedding ceremony is a symbol of what will take place in the marriage bed. Just as the two become one through their words spoken in wedding vows, so these words are a sign of the physical oneness that they will consummate later on. The lifting of the veil is a symbol and anticipation of this.[79][85]

Christianity

In Christian theology, St. Paul's words concerning how marriage symbolizes the union of Christ and His Church underlie part of the tradition of veiling in the marriage ceremony.[46][80] In Catholic traditions, the veil is seen as "a visible sign that the woman is under the authority of a man" and that she is submitting herself to her husband's Christ-like leadership and loving care.[47][88]

The removing of the veil can be seen as a symbol of the temple veil that was torn when Christ died, giving believers direct access to God, and in the same way, the bride and the groom, once married, now have full access to one another.[80][89]

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

In 2019 a letter by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints President Russell M. Nelson and his counselors, Dallin H. Oaks and Henry B. Eyring, declared that "Veiling the faces of deceased, 'endowed' [members who have been through a temple ceremony] women prior to burial is optional"; previously it had been required. The letter went on to say that such veiling, "may be done if the sister expressed such a desire while she was living. In cases where the wishes of the deceased sister on this matter are not known, her family should be consulted."[90] That same year veiling of women during part of the temple endowment ceremony was also made optional where it had been required before.[90]

Mourning veils

Veils remained a part of Western mourning dress customs into the early 20th century.[91] The tradition of widow's veiling has its roots in nun's attire, which symbolized modesty and chastity, and the mourning veil became a way to demonstrate sincerity and piety.[92] The mourning veil was commonly seen as a means of shielding the mourner and hiding her grief,[91][92] and, on the contrary, seen by some women as a means of publicly expressing their emotions. Widows in the Victorian era were expected to wear mourning veils for at least three months and up to two and a half years, depending on the custom.[92][93][94]

Mourning veils have also been sometimes perceived as expressions of elegance or even sex appeal. In a 19th-century American etiquette book one finds: "Black is becoming, and young widows, fair, plump, and smiling, with their roguish eyes sparkling under their black veils are very seducing".[95]

Interpretations

One view is that as a religious item, it is intended to honor a person, object or space. The actual sociocultural, psychological, and sociosexual functions of veils have not been studied extensively but most likely include the maintenance of social distance and the communication of social status and cultural identity.[96][97]

A veil also has symbolic interpretations, as something partially concealing, disguising, or obscuring.

Etymology

The English word veil ultimately originates from Latin vēlum, which also means "sail," from Proto-Indo-European *wegʰslom, from the verbal root *wegʰ- "to drive, to move or ride in a vehicle" (compare way and wain) and the tool/instrument suffix *-slo-, because the sail makes the ship move. Compare the diminutive form vexillum, and the Slavic cognate veslo "oar, paddle", attested in Czech and Serbo-Croatian.

See also

References

Notes

- Ahmed, Leila (1992). Women and Gender in Islam. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 15.

- Graeber, David (2011). Debt: The First 5000 Years. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House. p. 184. ISBN 9781933633862. LCCN 2012462122.

- El Guindi, Fadwa; Sherifa Zahur (2009). Hijab. The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195305135.001.0001. ISBN 9780195305135.

- Stol, Marten (2016). Women in the Ancient Near East. Richardson, Helen,, Richardson, M. E. J. (Mervyn Edwin John), 1943–. Boston: De Gruyter. p. 676. ISBN 9781614512639. OCLC 957696695.

- Ahmed 1992, p. 26-28.

- Found on the PY Ab 210 and PY Ad 671 tablets. "The Linear B word a-pu-ko-wo-ko". Palaeolexicon. Word study tool of ancient languages. Raymoure, K.A. "a-pu-ko-wo-ko". Minoan Linear A & Mycenaean Linear B. Deaditerranean. "PY 210 Ab (21)". "PY 671 Ad (23)". DĀMOS: Database of Mycenaean at Oslo. University of Oslo.

- Melena, Jose L. "Index of Mycenaean words".

- καλύπτρα, καλύπτω. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- Sebesta, Judith Lynn. "Symbolism in the Costume of the Roman Woman", pp. 46–53 in Judith Lynn Sebesta & Larissa Bonfante, The World of Roman Costume, University of Wisconsin Press 2001, p.48

- Fairley Raney, Rebecca (25 July 2011). "10 Wedding Traditions With Surprising Origins". HowStuffWorks. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- Laetitia La Follette (2001). "The Costume of the Roman Bridge". In Judith Lynn Sebesta; Larissa Bonfante (eds.). The World of Roman Costume. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 55–56. ISBN 9780299138547.

- Doni, Elena & Manuela Fulgenz, Il secolo delle donne. L’Italia del novecento al femminile, (The Women’s Century. Italian Women in the 20th Century), Laterza 2001, p. 5.

- Marrosu, Irene (18 December 2014). "Storia del costume sardo – Su muccadore (il copricapo)" [History of Sardinian costume]. La Donna Sarda (in Italian). Archived from the original on 8 March 2016.

- Ahmed 1992, p. 36.

- Esposito, John (1991). Islam: The Straight Path (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 99.

- Bloom, Jonathan; Blair, Sheila (2002). Islam: A Thousand Years of Faith and Power. Yale University Press. pp. 47. ISBN 0300094221.

- Silverstri, Sara (2016). "Comparing Burqa Debates in Europe". In Silvio Ferrari; Sabrina Pastorelli (eds.). Religion in Public Spaces: A European Perspective. Routledge. p. 276. ISBN 9781317067542.

- "Women in Afghanistan: the back story". www.amnesty.org.uk. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- Al Saied, Najat (2018). "Reactionary regimes use hijab law to control women — but so do liberalizing ones (paywall)". Washington Post.

- Secor, Anna (2002). "The Veil and Urban Space in Istanbul: Women's Dress, Mobility and Islamic Knowledge". Gender, Place & Culture. 9 (1): 5–22. doi:10.1080/09663690120115010.

- Björkman, W. (2012). "Lit̲h̲ām". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_4672.

- Allen Fromherz (2008). "Twareg". In Peter N. Stearns (ed.). Oxford Encyclopedia of the Modern World. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195176322.001.0001. ISBN 9780195176322.

- Ruth 3:15, American Standard Version (1901)

- Isaiah 3:22, American Standard Version (1901)

- Isaiah 25:7, American Standard Version (1901)

- Isaiah 28:20, American Standard Version (1901)

- 2 Corinthians 3:13, American Standard Version (1901)

- Exodus 34:33, American Standard Version (1901)

- 2 Corinthians 3:13, American Standard Version (1901)

- Exodus 26:31, American Standard Version (1901)

- 2 Chronicles 3:14, American Standard Version (1901)

- Matthew 27:51, American Standard Version (1901)

- Mark 15:38, American Standard Version (1901)

- Luke 23:45, American Standard Version (1901)

- Genesis 24:65, American Standard Version (1901)

- Genesis 38:14, American Standard Version (1901)

- Genesis 12:14, American Standard Version (1901)

- 1 Samuel 1:12, American Standard Version (1901)

- Song of Solomon 5:7, American Standard Version (1901)

- Isaiah 3:23, American Standard Version (1901)

- Exodus 26:36, American Standard Version (1901)

- Genesis 20:16, King James Version (Oxford Standard, 1769)

-

- Hempe, Forest (27 February 2017). "The Theology of the Veil". Catholic365.com. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Dictionary of French Architecture from 11th to 16th century [1856] by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

- Ephesians 5

- "The Theological Significance of the Veil". Veils by Lily. 7 April 2014. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Osburn, Carroll D. (1 July 2007). Essays on Women in Earliest Christianity, Volume 1. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 208. ISBN 9781556355400.

- Kraybill, Donald B. (5 October 2010). Concise Encyclopedia of Amish, Brethren, Hutterites, and Mennonites. JHU Press. p. 103. ISBN 9780801896576. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

During the 20th century, the wearing of head coverings declined in more assimilated groups, which gradually interpreted the Pauline teaching as referring to cultural practice in the early church without relevance for women in the modern world. Some churches in the mid-20th century had long and contentious discussions about wearing head coverings because proponents saw its decline as a serious erosion of obedience to scriptural teaching.

- Muir, Edward (18 August 2005). Ritual in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 9780521841535. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

In England radical Protestants, known in the seventeenth century as Puritans, we especially ardent in resisting the churching of women and the requirement that women wear a head covering or veil during the ceremony. The Book of Common Prayer, which became the ritual handbook of the Anglican Church, retained the ceremony in a modified form, but as one Puritan tract put it, the "churching of women after childbirth smelleth of Jewish purification."

- Yearbook of American & Canadian Churches 2012. Abingdon Press. 1 April 2012. p. 131. ISBN 9781426746666. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

The holy kiss is practiced and women wear head coverings during prayer and worship.

- Nash, Tom (24 April 2017). "How Women Came to Be Bare-Headed in Church". Catholic Answers. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Henold, Mary J. (2008). Catholic and Feminist: The Surprising History of the American Catholic Feminist Movement. UNC Press Books. p. 126. ISBN 9780807859476. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

At that time, official practice still dictated that Catholic women cover their heads in church.

- The Lutheran Liturgy: Authorized by the Synods Constituting The Evangelical Lutheran Synodical Conference of North America. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House. 1941. p. 427.

- Morgan, Sue (23 June 2010). Women, Gender and Religious Cultures in Britain, 1800–1940. Taylor & Francis. p. 102. ISBN 9780415231152. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

Several ardent Methodist women wrote to him, asking for his permission to speak. Mar Bosanquet (1739–1815) suggested that if Paul had instructed women to cover their heads when they spoke (1. Cor. 11:5) then he was surely giving direction on how women should conduct themselves when they preached.

- John Knox, "The first blast of the trumpet against the monstruous regiment of women", Works of John Knox, David Laing, ed. (Edinburgh: Printed for the Bannatyne Club), IV:377

- Seth Skolnitsky, trans., Men, Women and Order in the Church: Three Sermons by John Calvin (Dallas, TX: Presbyterian Heritage Publications, 1992), pp. 12,13.

- Hausa in Benin. "Joshua Project".

- Hostetler, John (1997). Hutterite Society. The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-8018-5639-6.

- Thompson, Charles (2006). The Old German Baptist Brethren: Faith, Farming, and Change in the Virginia Blue Ridge. University of Illinois Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-252-07343-4.

- Crump, William D. (30 August 2013). The Christmas Encyclopedia, 3d ed. McFarland. p. 298. ISBN 9781476605739.

- DeMello, Margo (14 February 2012). Faces around the World. ABC-CLIO. p. 303. ISBN 9781598846188. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- Kellou, Dorothée Myriam. Algerian women take to streets to bring back traditional veil. The Observers. 16 March 2015. Accessed on 5 March 2016.

- Review of Herrin book and Michael Angold. Church and Society in Byzantium Under the Comneni, 1081–1261. Cambridge University Press. 21 September 2000. pp. 426–7. ISBN 978-0-521-26986-5. see also John Esposito (2005). Islam: The Straight Path (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 98.

- Ahmad Hasan Dani; Vadim Mikhaĭlovich Masson; Unesco (1 January 2003). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in contrast : from the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. UNESCO. pp. 357–. ISBN 978-92-3-103876-1.

- Abdullaev, Kamoludin; Shahram Akbarzaheh (27 April 2010). Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan. Scarecrow Press. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-0-8108-6061-2.

- Abdullaev 2010, p. 381.

- Pannier, Bruce (1 April 2015). "Central Asia's Controversial Fashion Statements". Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty.

- Ellen Barry (18 March 2013). "Local Russian Hijab Ban Puts Muslims in a Squeeze". The New York Times.

- "Islamic Veil Across Europe". BBC News. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- "French ban on the wearing in public of clothing designed to conceal one's face does not breach the Convention ECHR 191" (PDF). BBC News/ECHR. ECHR. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- Sadashiv Altekar, Anant (1956). The Position of Women in Hindu Civilization, from Prehistoric Times to the Present Day. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 171–175. ISBN 9788120803244.

- Kelen, Betty (1967). Gautama Buddha in Life and Legend. Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Company. pp. 7–8.

- Singh, Sardar Harjeet (2009). The Position of Women in Hindu Civilization. p. 259.

- Jhutti-Johal, Jagbir (2011). Sikhism Today. A&C Black. p. 35. ISBN 9781847062727.

- Susong, Liz (28 September 2017). "Wedding Veil Traditions Explained". Brides. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- "History behind the bridal veil". Richmond Times-Dispatch. 7 July 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- Mikkelson, Barbara (27 June 2005). "FACT CHECK: Wedding Veil". Snopes. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- "What is the Symbolism of a Bride's Veil?". WiseGeek. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Fairchild, Mary (20 May 2018). "Uncover the Meaning Behind Today's Christian Wedding Traditions". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- Markel, Katrina (25 April 2011). "The Meaning of Wedding Traditions...and What to Watch for Friday". Lipstick & Politics. Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- Paez, Tory (5 May 2010). "Remedies for Sexism in Christian Weddings". Academia. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- Monger, George (2004). Marriage Customs of the World: From Henna to Honeymoons. Social Science.

- Ingrassia, Catherine (2007). "Diana, Martha and Me". In Curran, Colleen (ed.). Altared: bridezillas, bewilderment, big love, breakups, and what women really think about contemporary weddings. New York: Vintage Books. pp. 24–30. ISBN 978-0-307-27763-3.

- Grate, Rachel (17 June 2016). "7 Surprisingly Sexist Wedding Traditions We Should Change Immediately". Mic. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- "Bridal Crown History from Sweden". Ingebretsen's Nordic Marketplace. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- Shurpin, Yehuda. "Why Does a Jewish Bride Wear a Veil on Her Face?". Chabad.org. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- 1 Corinthians 11:4

- 1 Corinthians 7:4

- https://www.sltrib.com/religion/2019/01/29/heels-temple-changes/

- Peffer, Mary (14 October 2016). "Funeral fashion has become more lax, but there are still rules". Today. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Sears, Jocelyn (29 March 2018). "Wearing a 19th-Century Mourning Veil Could Result in – Twist – Death". Racked. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- "Dearly Departed...a glimpse into Victorian mourning traditions". Stagecoach Inn Museum. 28 October 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Nehring, Abigail (29 September 2017). "Do Women Still Wear Veils to Funerals?". Our Everyday Life. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Baker, Lindsay (3 November 2014). "Mourning glory: Two centuries of funeral dress". BBC Culture. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- Murphy, R.F. (1964). Social Distance and the Veil. American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 66, No. 6, Part 1, pp. 1257–1274

- Brenner, S. (1996). Reconstructing Self and Society: Javanese Muslim Women and "The Veil". American Ethnologist, Vol. 23, No. 4, pp. 673–697

Further reading

- Heath, Jennifer (ed.). (2008). The Veil: Women Writers On Its History, Lore, And Politics. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-25518-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to veils. |

- Curtain article from the Jewish Encyclopedia