Ceftazidime

Ceftazidime, sold under the brand names Fortaz among others, is an antibiotic useful for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections.[1] Specifically it is used for joint infections, meningitis, pneumonia, sepsis, urinary tract infections, malignant otitis externa, Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection, and vibrio infection.[1] It is given by injection into a vein, muscle, or eye.[1][2]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /sɛfˈtæzɪdiːm/ |

| Trade names | Fortaz, Tazicef, others[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a686007 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Intravenous, intramuscular, inhalation |

| Drug class | Third-generation cephalosporin |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 91% (IM) |

| Metabolism | negligible |

| Elimination half-life | 1.6–2 hours |

| Excretion | 90–96% kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.069.720 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C22H22N6O7S2 |

| Molar mass | 546.57 g·mol−1 |

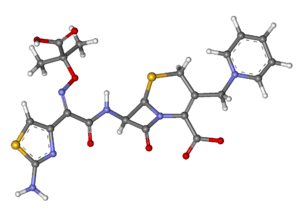

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Common side effects include nausea, allergic reactions, and pain at the site of injection.[1] Other side effects may include Clostridium difficile diarrhea.[1] It is not recommended in people who have had previous anaphylaxis to a penicillin.[1] Its use is relatively safe during pregnancy and breastfeeding.[3] It is in the third-generation cephalosporin family of medications and works by interfering with the bacteria's cell wall.[1]

Ceftazidime was patented in 1978 and came into commercial use in 1984.[4] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[5] Ceftazidime is available as a generic medication.[1]

Medical uses

Ceftazidime is used to treat lower respiratory tract, skin, urinary tract, blood-stream, joint, and abdominal infections, and meningitis.[6] The drug is given intravenously (IV) or intramuscularly (IM) every 8–12 hours (two or three times a day), with dose and frequency varying by the type of infection, severity, and/or renal function of the person. Ceftazidime is also commonly prescribed off-label for nebulization in people with cystic fibrosis for the suppression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the lungs as well as the treatment of pulmonary exacerbations. Those with kidney disease are dosed less frequently.[6]

Ceftazidime is the first-line treatment for the tropical infection, melioidosis, an important cause of sepsis in Asia and Australia.[7][8]

Labeled indications include the treatment of patients with:

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections

- other Gram-negative, aerobic infections

- neutropenic fever[9]

As a class, cephalosporins have activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. The balance of activity tips toward Gram-positive organisms for earlier generations; later generations of cephalosporins have more Gram-negative coverage. Ceftazidime is one of the few in this class with activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. It is not active against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Spectrum of activity

Clinically relevant organisms against which ceftazidime has activity include:

- Gram-negative aerobes such as Enterobacter, Escherichia coli, Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella spp., Proteus spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Neisseria meningitidis

- Gram-positive aerobes, such as group B streptococci, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Streptococcus pyogenes

- Anaerobes, such as Bacteroides spp.[6]

The following represents MIC susceptibility data for a few clinically significant pathogens:

- Escherichia coli – 0.015 μg/mL – 512 μg/mL

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa – ≤0.03 μg/mL – 1024 μg/mL [10]

Side effects

Ceftazidime is generally well tolerated. When side effects occur, they are most commonly local effects from the intravenous line site, allergic reactions, and gastrointestinal symptoms. According to one manufacturer, in clinical trials, allergic reactions including itching, rash, and fever, happened in fewer than 2% of patients. Rare but more serious allergic reactions, such as toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme, have been reported with this class of antibiotics, including ceftazidime. Gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, were reported in fewer than 2% of patients.[6]

Another source reported, in addition, blood tests of patients may show increased eosinophils (8%), increased lactate dehydrogenase (6%), increased gamma-glutamyl transferase (5%), positive direct Coombs test (4%), increased platelets (thrombocythemia) (2%), increased ALT (7%), increased AST (6%), or increased alkaline phosphatase (4%).[9]

Contraindications

Ceftazidime is contraindicated in people with a known allergy to ceftazidime or to any other cephalosporin antibiotic.[6]

Precautions

Ceftazidime is mainly eliminated by the kidneys into the urine. As such, drug levels in the blood may build up in persons with kidney injury or kidney disease. This includes those on dialysis. In these cases of renal impairment, the drug is dosed less frequently.[9] No dose adjustment is needed for those with liver disease.

Pregnancy

Ceftazidime falls under the pregnancy category B.[9] According to the manufacturer, research studies in mice and rats showed no evidence of harm to the fetus, even at up to 40 times the human dose of ceftazidime. Importantly, though, no high-quality research studies of the effects of the drug in pregnant women were conducted.[6]

Mechanism of action

Third-generation cephalosporins differ from earlier generations in the presence of a C=N-OCH3 group in their chemical structure (cefuroxime & cefuzonam also bear this functional group but are only listed as class II). This group provides improved stability against certain beta-lactamase enzymes produced by Gram-negative bacteria. These bacterial enzymes rapidly destroy earlier-generation cephalosporins by breaking open the drug's beta-lactam chemical ring, leading to antibiotic resistance. Though initially active against these bacteria, with widespread use of third-generation cephalosporins, some Gram-negative bacteria that produce extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) are even able to inactivate the third-generation cephalosporins. Infections caused by ESBL-producing Gram-negative bacteria are of particular concern in hospitals and other healthcare facilities.[11]

Chemistry

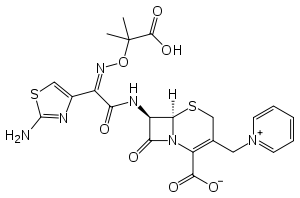

In addition to the syn-configuration of the imino side chain, compared to other third-generation cephalosporins, the more complex moiety (containing two methyl and a carboxylic acid group) confers extra stability to β-lactamase enzymes produced by many Gram-negative bacteria. The extra stability to β-lactamases increases the activity of ceftazidime against otherwise resistant Gram-negative organisms including Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The charged pyridinium moiety increases water-solubility. Ceftazidime shares the same variable R-group side chain with aztreonam, a monobactam antibiotic; the two drugs share a similar spectrum of activity, including activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

See also

References

- "Ceftazidime". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- "Intravitreal Injections - EyeWiki". eyewiki.aao.org. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 87. ISBN 9781284057560.

- Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 495. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Ceftazidime for Injection(R) [package insert]. Schaumburg, IL: Sagent; 2012. PDF of insert Archived 2014-04-23 at the Wayback Machine

- White NJ (2003). "Melioidosis". Lancet. 361 (9370): 1715–722. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13374-0. PMID 12767750.

- White, N. J.; Dance, D. A.; Chaowagul, W; Wattanagoon, Y; Wuthiekanun, V; Pitakwatchara, N (1989). "Halving of mortality of severe melioidosis by ceftazidime". Lancet. 2 (8665): 697–701. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90768-X. PMID 2570956.

- Lexicomp Online, Lexi-Drugs, Hudson, Ohio: Lexi-Comp, Inc.; 2014; April 20, 2014. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-04-23. Retrieved 2014-04-21.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.toku-e.com/Assets/MIC/Ceftazidime%20pentahydrate.pdf

- Sharma M, Pathak S, Srivastava P (October 2013). "Prevalence and antibiogram of Extended Spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL) producing Gram negative bacilli and further molecular characterization of ESBL producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp". J Clin Diagn Res. 7 (10): 2173–7. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2013/6460.3462. PMC 3843424. PMID 24298468.