Francisco de Orellana

Francisco de Orellana Bejarano Pizarro y Torres de Altamirano (Spanish pronunciation: [fɾanˈθisko ðe oɾeˈʝana]; 1511 – November 1546) was a Spanish explorer and conquistador. He completed the first known navigation of the entire length of the Amazon River, which initially was named "Rio de Orellana." He also founded the city of Guayaquil in what is now Ecuador.

Francisco de Orellana | |

|---|---|

Image of a bust of Francisco de Orellano with a patch over his left eye | |

| Born | 1511 |

| Died | November 1546 (aged 34–35) |

| Nationality | Castilian (Spanish) |

| Occupation | Conquistador |

| Employer | Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor |

| Known for | First known navigation through the length of the Amazon River |

| Spouse(s) | Ana de Ayala |

Orellana died during a second expedition on the Amazon.

Background

Born in Trujillo (various birth dates, ranging from 1490 to 1511, are still quoted by biographers), Orellana was a close friend and possibly a relative of Francisco Pizarro, the Trujillo-born conquistador of Peru (his cousin, according to some historians). He traveled to the New World (probably in 1527). Orellana served in Nicaragua until joining Pizarro's army in Peru in 1533, where he supported Pizarro in his conflict with Diego de Almagro (1538). After the victory over De Almagro's men, he was appointed governor of La Culata and re-established the town of Guayaquil, previously founded by Pizarro and repopulated by Sebastián de Belalcázar. (During the civil war he sided with the Pizarros and was Ensign General of a force sent by Francisco Pizarro from Lima in aid of Hernando Pizarro. He was granted land at Puerto Viejo, on the coast of Ecuador.)

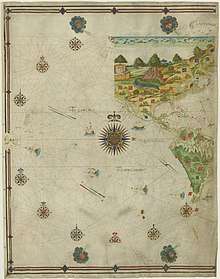

First exploration of the Amazon River

In 1540 Gonzalo Pizarro arrived in Quito as governor and was charged by Francisco Pizarro with an expedition to locate the "Land of Cinnamon", thought to be somewhere to the east. Orellana was one of Gonzalo Pizarro's lieutenants during his 1541 expedition east of Quito into the South American interior. In Quito, Gonzalo Pizarro collected a force of 220 Spaniards and 4000 natives, while Orellana, as second in command, was sent back to Guayaquil to gather troops and horses. Pizarro left Quito in February 1541 just before Orellana arrived with his 23 men and horses. Orellana hurried after the main expedition, eventually making contact with them in March. However, by the time the expedition had left the mountains, 3000 natives and 140 Spanish had either died or deserted.

On reaching the River Coca (a tributary of the Napo), a brigantine, the San Pedro, was constructed to ferry the sick and supplies. Gonzalo Pizarro ordered him to explore the Coca River and return after finding the river's end. When they arrived at the confluence with the Napo River, his men threatened to mutiny if they did not continue. On 26 December 1541 he agreed to be elected chief of the new expedition and to conquer new lands in name of the king. Orellana (with the Dominican Gaspar de Carvajal who chronicled the expedition) and 50 men set off downstream to find food. Unable to return against the current, Orellana waited for Pizarro, finally sending back three men with a message, and started construction of a second brigantine, the Victoria. Pizarro had in the meantime returned to Quito by a more northerly route, by then with only 80 men left alive.

After leaving the village on the Napo, Orellana continued downstream to the Amazon. The 49 men began to build a bigger ship for river navigation. During their navigation on Napo River they were threatened constantly by the Omaguas. They reached the Negro River on 3 June 1542 and finally arrived on the Amazon River.

At a longitude of about 69°W Orellana and his men were involved in a skirmish with Machiparo's natives and were chased downstream. Continuing downstream they consecutively passed the Rio de la Trinidad (= Rio Jurua?), the Pueblo Vicioso, the Rio Negro (named by Orellana), the Pueblo del Corpus, the Pueblo de los Quemados and the Pueblo de la Calle at about 57°W. There they entered the territory of the Pira-tapuya. The name 'Amazon' is said to arise from a battle Francisco de Orellana fought with a tribe of Tapuyas. The women of the tribe fought alongside the men, as was the custom among the tribe. Orellana derived the name Amazonas from the mythical Amazons of Asia described by Herodotus (see The Histories [4.110-116]) and Diodorus in Greek legends. A skirmish with these South American warrior women[1] allegedly took place on 24 June 1542 while Orellana was approaching the Trombetus River, in the neighborhood of the Ilha Tupinambarama at the junction with the River Madeira.

At about 54°W they stopped for 18 days to repair the boats, and finally reached the open sea on 26 August 1542, and checked the boats for seaworthiness. While coasting towards Guiana the brigs were separated until reunited at Nueva Cadiz on Cubagua island off the coast of Venezuela. The Victoria, carrying Orellana and Carvajal, passed south around Trinidad and was trapped in the Gulf of Paria for seven days, finally reaching Cubagua on 11 September 1542. The San Pedro sailed north of Trinidad and reached Cubagua on 9 September.

.svg.png)

Second voyage and its preparation

From Cubagua, Orellana decided to return to Spain to obtain from the Crown the governorship over the discovered lands, which he named New Andalusia. After a difficult navigation, he touched first the shores of Portugal. The king received him in a friendly way and made him an offer to go back to the Amazon under a Portuguese flag. Orellana's exploration produced an international issue. According to the Treaty of Tordesillas, the majority of the Amazon River should belong to Spain, but the mouth should be ruled by Portugal. Orellana refused the Portuguese offer and went to Valladolid. After nine months of negotiations, Charles I appointed him governor of New Andalusia[2] on February 18, 1544. The charter established that he should explore and settle the Amazonian lands with less than 300 men and 100 horses, and found two cities, one in the mouth and another in the interior of the basin.[2]

After captivating the Spanish court with tales and alleged exaggerations of his voyage down the Amazon, Orellana, after nine months deliberation, obtained a commission to conquer the regions he had discovered. It permitted him to explore and settle Nueva Andalucia, with no fewer than 200 infantrymen, 100 horsemen and the material to construct two river-going ships. On his arrival at the Amazon, he was to build two towns, one just inside the mouth of the river. The commission was accepted on 18 February 1544, but preparations for the voyage were frustrated by unpaid debts, Portuguese spies and internal wranglings. Sufficient funds were raised through the efforts of Cosmo de Chaves, Orellana's stepfather, but the problems were compounded by Orellana's decision to marry a very young and poor girl, Ana de Ayala, whom he intended to take with him (along with her sisters). It was only on the arrival of a Portuguese spy fleet at Seville that Orellana's creditors relented and allowed him to sail. On reaching Sanlucar he was detained again, the authorities having discovered a shortfall in his complement of men and horses, and the fact that large numbers of his crew were not Spanish. On 11 May 1545 Orellana (in hiding on one of his own vessels) surreptitiously sailed out of Sanlucar with four ships and disappeared from view.

He sailed first for the Canary Islands, where he spent three months trying to re-supply his ships, then another two months at the Cape Verde Islands. By then one ship had been lost, 98 men had died of sickness and 50 had deserted. A further ship was lost in mid-Atlantic, carrying with it 77 crew, 11 horses and a boat to be used on the Amazon. Orellana arrived at the Brazilian coast shortly before Christmas 1545 and proceeded 100 leagues into the Amazon Delta.

A river-going vessel was constructed, but 57 men died from hunger and the remaining seagoing vessel was driven ashore. The marooned men found refuge among friendly indigenous people on an island in the delta, while Orellana and a boat delegation set off to find food and locate the principal arm of the Amazon. On returning to the shipwreck camp, they found it deserted, the men having constructed a second boat and set out to find Orellana. The second boat eventually gave up the search and made its way along the coast to the island of Margarita near the Venezuela coast. Orellana and his boat crew set out again to locate the principal channel, and were subsequently attacked by natives. 17 were killed by poisoned arrows, while Orellana himself died of illness and grief, sometime in November 1546.

The second boat crew, on arriving at Margarita, found 25 of their companions, including Ana de Ayala, who had arrived there on a ship of the original fleet. The total of 44 survivors (out of an estimated 300) were eventually rescued by a Spanish ship. Many of them settled in Central America, Peru and Chile, while Ana de Ayala befriended another survivor, Juan de Penalosa, whom she lived with for the rest of her days in Panama. She was last heard of in 1572.

Significance of Orellana's first Amazon River voyage

The indigenous dominated the area close to the Amazon River. When Orellana went down the river in search of new territories, descending from the Andes in 1541, the river was still called Rio Grande, Mar Dulce or Rio de Canela (Cinnamon), because cinnamon trees were once thought to be located there. The story of the fierce ambush launched by the Icamiabas that nearly destroyed the Spanish expedition was narrated to the king, Charles I, who, inspired by the Greek legend of the Amazons, named the river the Amazon.

In one of the most improbably successful voyages in known history, Orellana managed to sail the length of the Amazon, arriving at the river's mouth on 24 August 1542. He and his party sailed along the Atlantic coast until reaching Cubagua Island, near the coast of Venezuela.

The BBC documentary Unnatural Histories presents evidence that Orellana, rather than exaggerating his claims as previously thought, was correct in his observations that an advanced civilization was flourishing along the Amazon in the 1540s. It is believed that the civilization was later devastated by the spread of diseases from Europe, such as smallpox.[3] The evidence to support this claim comes from the discovery of numerous geoglyphs dating from between 1 and 1250 AD and terra preta.[4] Some 5 million people may have lived in the Amazon region in 1500, divided between dense coastal settlements, such as that at Marajó, and inland dwellers.[5] By 1900, the population had fallen to 1 million and by the early 1980s, it was less than 200,000.[5]

Places named after Orellana

Historical chronicles

Gaspar de Carvajal, the chaplain and chronicler of the first expedition, wrote Relación del nuevo descubrimiento del famoso río Grande que descubrió por muy gran ventura el capitán Francisco de Orellana,[6] which was partly reproduced in Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés's Historia general y natural de las Indias (1542),[7] who included in addition statements by Orellana and some of his men. Carvajal's work was published in 1894 by the Chilean historian José Toribio Medina, as part of his book Descubrimiento del río de las Amazonas.[8]

In popular culture

De Orellana's voyages served as partial inspiration for the film Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972). An earlier script, penned by director Werner Herzog, also deliberately included De Orellana in the movie, but he was ultimately left out. De Orellana's role in the search for El Dorado also forms part of the plot of the film Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008).

William Ospina's 2008 novel El país de la canela (The Cinnamon Country) includes a novelized version of Orellana's trip.[9]

One of the campaigns of Age of Empires II: The Forgotten is called El Dorado and is about the quest of Francisco de Orellana and Francisco Pizarro to find El Dorado, the legendary Lost City of Gold, thought to be hidden somewhere in the vast Amazon rainforest. The campaign is based on De Orellana's first exploration.

References

- Mann, Charles (2011). 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus (Second ed.). Vintage. p. 324.

- Frank Jacobs (June 19, 2012). "Amazonia or Bust!". The New York Times. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- "Unnatural Histories - Amazon". BBC Four.

- Simon Romero (January 14, 2012). "Once Hidden by Forest, Carvings in Land Attest to Amazon's Lost World". The New York Times.

- Chris C. Park (2003). Tropical Rainforests. Routledge. p. 108.

- Toribio Medina, José (1942). "Fray Gaspar de Carvajal: Vicario de Quito". In Julio Tobar Donoso (ed.). Historiadores y cronistas de las misiones. Miguel de Cervantes Virtual Library. Quito: Biblioteca Ecuatoriana Minima. pp. 423–471.

- Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, Gonzalo (1851). José Amador de los Ríos (ed.). Historia general y natural de las Indias. Miguel de Cervantes Virtual Library. Madrid: La Real Acadameia de La Historia.

- Toribio Medina, José (1894). Descubrimiento del río de las Amazonas. Seville: Imprenta de E. Rasco. Retrieved 2020-07-15.

- Ospina, William (2008). El país de la canela. Bogotá: Grupo Editorial Norma. ISBN 978-9584515117. Retrieved 2020-07-15.

Further reading

- Dalby, A., "Christopher Columbus, Gonzalo Pizarro, and the search for cinnamon" in Gastronomica (Spring 2001).

- Smith, A. (1994). Explorers of the Amazon. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-76337-4

- Levy, Buddy (2011). "River of Darkness: Francisco Orellana's Legendary Voyage of Death and Discovery Down the Amazon." New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-80750-9

- Warêgne, Jean-Marie (2014); "Francisco de Orellana découvreur de l'Amazone"; Paris:L'Harmattan.ISBN 978-2-343-02742-5

- Millar, George: A Crossbowman's Story. Knopf, 1954. fictionalised story of the Orellana expedition.

External links

| Library resources about Francisco de Orellana |