Maya Hero Twins

The Maya Hero Twins are the central figures of a narrative included within the colonial Kʼicheʼ document called Popol Vuh, and constituting the oldest Maya myth to have been preserved in its entirety. Called Hunahpu (Junajpuʼ) and Xbalanque (Ixbʼalankeʼ) in the Kʼicheʼ language, the Twins have also been identified in the art of the Classic Mayas (200–900 AD). The twins are often portrayed as complementary forces. The complementary pairings of life and death, sky and earth, day and night, Sun and Moon, among multiple others have been used to represent the twins. The duality that occurs between male and female is often seen in twin myths, as a male and female twin are conceptualized to be born to represent the two sides of a single entity (Miller and Taube 1993: 81).

.jpg)

The Twin motif recurs in many Native American mythologies; the Maya Twins, in particular, could be considered as mythical ancestors to the Maya ruling lineages.

The Hero Twins in word and image

Summoned to Xibalba by the Lords of the Underworld, the father and uncle were defeated and sacrificed. Two sons were conceived, however, by the seed of the dead father. The pregnant mother fled from Xibalba. The sons—or 'Twins'—grew up to avenge their father, and after many trials, finally defeated the lords of the Underworld in the ballgame. The Popol Vuh features other episodes involving the Twins as well (see below), including the destruction of a pretentious bird demon, Vucub Caquix, and of his two demonic sons. The Twins also turned their half-brothers into the howler monkey gods, who were the patrons of artists and scribes. The Twins were finally transformed into sun and moon, signaling the beginning of a new age. the Qʼeqchiʼ myth of Sun and Moon, where he is hunting for deer (a metaphor for making captives), and capturing the daughter of the Earth Deity. In these cases, Hunahpu has no role to play.

Iconography

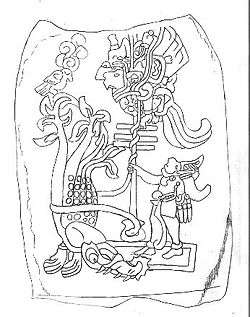

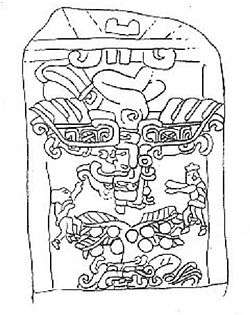

Another main source for Hero Twin mythology is much earlier and consists of representations found on Maya ceramics until about 900 AD and in the Dresden Codex some centuries later.[3] Clearly recognizable are the figures of Hunahpu, Xbalanque, and the howler monkey scribes and sculptors. Hunahpu is distinguished by black spots on his skin, showing the spirit of the jaguar. On the Preclassic murals from San Bartolo (Maya site), the king, marked with a black spot on the cheek, and drawing blood from his genitals in the four corners of the world, appears to personify the hero Hunahpu. Xbalanque—the 'War Twin'—is more animal-like, in that he is distinguished by jaguar patches on his skin and by whiskers or a beard.

Certain iconographic scenes are suggestive of episodes in the Popol Vuh. The Twins' shooting of a steeply descending bird (the 'Principal Bird Deity') with blowguns may represent the defeat of Vucub-Caquix, whereas the principal Maya maize god rising from the carapace of a turtle in the presence of the Hero Twins may visualize the resurrection of the Twins' father, Hun-Hunahpu. This second scene has also been explained differently, however.[4] In any case, the Twins are often depicted together with the main maize god, and these three semi-divinities were obviously felt to belong together. Therefore, it is probably no coincidence that in the Popol Vuh, the Twins are symbolically represented by two maize stalks.

Names and calendrical functions

The name "Xbalanque" (pronounced [ʃɓalaŋˈke]) has been variously translated as 'Jaguar Sun' (x-balam-que), 'Hidden Sun' (x-balan-que), and 'Jaguar Deer' (x-balam-quieh). The initial sound may stem from yax (precious), since in Classical Maya, a hieroglyphic element of this meaning precedes the pictogram of the hero (although it has also been suggested to be the female prefix ix-). For the combination of prefix and pictogram, a reading as Yax Balam has been proposed. The name "Hunahpu" (pronounced [hunaxˈpu]) is usually understood as Hun-ahpub 'One-Blowgunner', the blowgun characterizing the youthful hero as a hunter of birds.

The head of Hunahpu is used as a variant sign for the 20th day in the day count or tzolkin, which in these cases may actually have been read as (Hun)ahpu, rather than Ahau (Lord or King). The 20th day is also the concluding day of all vigesimal periods, including the katun and baktun. The head of Xbalanque is used as a variant for the number nine (balan being similar to bolon 'nine').

Twin myth summary

The following is a detailed summary of the Popol Vuh Twin Myth, on from the death of the heroes' father and uncle.[5]

Early life of the heroes

Hunahpu and his brother were conceived when their mother Xquic, daughter of one of the lords of Xibalba, spoke with the severed head of their father Hun. The skull spat upon the maiden's hand, which caused the twins to be conceived in her womb. Xquic sought out Hun Hunahpu's mother, who begrudgingly took her as a ward after setting up a number of trials to prove her identity.

Even after birth, Hunahpu and Xbalanque were not well treated by their grandmother or their older half-brothers, One Howler Monkey and One Artisan. Immediately after their births, their grandmother demanded they be removed from the house for their crying, and their elder brothers obliged by placing them on an anthill and among the brambles. Their intent was to kill their younger half-brothers out of jealousy and spite, for the older pair had long been revered as fine artisans and thinkers and feared the newcomers would steal from the attention they received.

The attempts to kill the young twins after birth were a failure, and the boys grew up without any obvious spite for their ill-natured older siblings. During their younger years, the twins were made to labor, going to hunt birds which they brought back for meals. The elder brothers were given their food to eat first, in spite of the fact they spent the day singing and playing while the younger twins were working.

Hunahpu and Xbalanque demonstrated their wit at a young age in dealing with their older half brothers. One day, the pair returned from the field without any birds to eat and were questioned by their older siblings. The younger boys claimed that they had indeed shot several birds but that they had gotten caught high in a tree and were unable to retrieve them. The older brothers were brought to the tree and climbed up to get the birds when the tree suddenly began to grow even taller, and the older brothers were caught. This is also the first instance in which the twins demonstrate supernatural powers, or perhaps simply the blessings of the greater gods; the feats of power are often only indirectly attributed to the pair.

Hunahpu further humiliated his older brethren by instructing them to remove their loincloths and tie them about their waists in an attempt to climb down. The loincloths became tails, and the brothers were transformed into monkeys. When their grandmother was informed that the older boys had not been harmed, she demanded they be allowed to return. When they did come back to the home, their grandmother was unable to contain her laughter at their appearance, and the disfigured brothers ran away in shame.[6]

Defeat of Seven Macaw and his family

At a point in their lives not specified in the Popol Vuh, the twins were approached by the god Huracan regarding an arrogant god named Seven Macaw (Vucub Caquix). Seven Macaw had built up a following of worshipers among some of the inhabitants of the Earth, making false claims to be either the sun or the moon. Seven Macaw was also extremely vain, adorning himself with metal ornaments in his wings and a set of false teeth made of gemstones.

In a first attempt to dispatch the vain god, the twins attempted to sneak up on him as he was eating his meal in a tree, and shot at his jaw with a blowgun. Seven Macaw was knocked from his tree but only wounded, and as Hunahpu attempted to escape, his arm was grabbed by the god and torn off.

In spite of their initial failure, the twins again demonstrated their clever nature in formulating a plan for Seven Macaw's defeat. Invoking a pair of gods disguised as grandparents, the twins instructed the invoked gods to approach Seven Macaw and negotiate for the return of Hunahpu's arm. In doing so, the "grandparents" indicated they were but a poor family, making a living as doctors and dentists and attempting to care for their orphaned grandchildren. Upon hearing this, Seven Macaw requested that his teeth be fixed since they had been shot and knocked loose by the blowgun, and his eyes cured (it is not specifically said what ailed his eyes). In doing so, the grandparents replaced his jeweled teeth with white corn and plucked the ornaments he had about his eyes, leaving the god destitute of his former greatness. Having fallen, Seven Macaw died, presumably of shame.

Seven Macaw's sons, Zipacna and Cabrakan, inherited a large part of their father's arrogance, claiming to be the creators and destroyers of mountains, respectively. The elder son Zipacna was destroyed when the twins tricked him with the lure of a fake crab, burying him beneath a mountain in the process.

The Maya god Huracan again implored the young twins for help in dealing with Seven Macaw's younger son, Cabrakan, the Earthquake. Again, it was primarily through their cleverness that the pair were able to bring about the downfall of their enemy, having sought him out and then using his very arrogance against him; they told the story of a great mountain they had encountered that kept growing and growing. Cabrakan prided himself as the one to bring down the mountains, and upon hearing such a tale, he predictably demanded to be shown the mountain. Hunahpu and Xbalanque obliged, leading Cabrakan toward the non-existent mountain. Being skilled hunters, they shot down several birds along the way, roasting them over fires and playing upon Cabrakan's hunger. When he asked for some meat, he was given a bird that had been prepared with plaster and gypsum, a poison to the god. Upon eating it, he was weakened and the boys were able to bind him and cast him into a hole in the earth, burying him forever.

Discovery of One Hunahpu's gaming equipment

Sometime after the expulsion of their older siblings, the twins used their special powers or abilities to expedite their gardening chores for their grandmother—a single swing of the axe would do a full day's worth of clearing, for example. The pair covered themselves in dust and wood chippings when their grandmother approached to make it seem they had been hard at work, in spite of the fact they spent the whole day relaxing. However, the next day they returned to find their work undone by the animals of the forest. Upon completion of their work, they hid and lay in wait, and when the animals returned, they attempted to catch or scare them off.

Most animals eluded their capture. The rabbit and the deer they caught by the tail, but these tails broke off, thus giving all future generations of rabbits and deer short tails. The rat, however, they did capture, singeing his tail over the fire in revenge for the act. In exchange for mercy, the rat revealed an important piece of information: the gaming equipment of their father and uncle was hidden by their grandmother in her grief, for it was playing ball that was directly responsible for the deaths of her sons.

Again, a ruse was devised to get their equipment, the twins once more relying upon trickery to meet their goals. The pair snuck the rat into their home during dinner and had their grandmother cook a meal of hot chili sauce. They demanded water for their meal, which their grandmother went to retrieve. The jar of water, however, had been sabotaged with a hole, and she was unable to return with the water. When their mother left to find out why and the pair were alone in the home, they sent the rat up into the roof to gnaw apart the ropes that held the equipment hidden and were able to retrieve the equipment their father and uncle had used to play ball. It had long been a favorite past-time for their father, and soon would become a favored activity for them as well.

Xibalban ballgames

Hunahpu and Xbalanque played ball in the same court that their father and his brother had played in long before them. When One Hunahpu and his brother had played, the noise had disturbed the Lords of Xibalba, rulers of the Maya Underworld. The Xibalbans summoned them to play ball in their own court.

When the twins began to play ball in the court, once again the Lords of Xibalba were disturbed by the racket, and sent summons to the boys to come to Xibalba and play in their court. Fearing they would suffer the same fate, their grandmother relayed the message only indirectly, telling it to a louse which was hidden in a toad's mouth, which was in turn hidden in the belly of a snake in a falcon. Nevertheless, the boys did receive the message, and much to their grandmother's dismay, set off to Xibalba.

When their father had answered the summons, he and his brother were met with a number of challenges along the way which served to confuse and embarrass them before their arrival, but the younger twins would not fall victim to the same tricks. They sent a mosquito ahead of them to bite at the Lords and uncover which were real and which were simply mannequins, as well as uncovering their identities. When they arrived at Xibalba, they were easily able to identify which were the real Lords of Xibalba and address them by name. They also turned down the Lords' invitation to sit on a bench for visitors, correctly identifying the bench as a heated stone for cooking. Frustrated by the twins' ability to see through their traps, they sent the boys away to the Dark House, the first of several deadly tests devised by the Xibalbans.

Their father One Hunahpu and his brother had suffered embarrassing defeats in each of the tests, but again Hunahpu and Xbalanque demonstrated their prowess by outwitting the Xibalbans on the first of the tests, surviving the night in the pitch black house without using up their torch. Dismayed, the Xibalbans bypassed the remaining tests and invited the boys directly to the game. The twins knew that the Xibalbans used a special ball that had a blade with which to kill them, and instead of falling for the trick, Hunahpu stopped the ball with a racquet and spied the blades. Complaining that they had been summoned only to be killed, Hunahpu and Xbalanque threatened to leave the game.

As a compromise, the Lords of Xibalba allowed the boys to use their own rubber ball, and a long and proper game ensued. In the end, the twins allowed the Xibalbans to win the game, but this was again a part of their ruse. They were sent to Razor House, the second deadly test of Xibalba, filled with knives that moved of their own accord. The twins, however, spoke to the knives and convinced them to stop, thereby ruining the test. They also sent leafcutting ants to retrieve petals from the gardens of Xibalba, a reward to be offered to the Lords for their victory. The Lords had intentionally chosen a reward they thought impossible, for the flowers were well guarded, but the guards did not take notice of the ants and were killed for their inability to guard the flowers.

The twins played a rematch with the Xibalbans and lost by intent again and were sent to Cold House, the next test. This test they defeated, as well. In turn, Hunahpu and Xbalanque by purpose lost their ballgames so that they might be sent to the remaining tests, Jaguar House, Fire House, Bat House, and in turn defeat the tests of the Xibalbans. The Lords of Xibalba were dismayed at the twins success until the twins were placed in Bat House. Though they hid inside their blowguns from the deadly bats, Hunahpu peeked out to see if daylight had come, and was decapitated by the bat god Camazotz.

The Xibalbans were overjoyed that Hunahpu had been defeated. Xbalanque summoned the beasts of the field, however, and fashioned a replacement head for Hunahpu. Though his original head was used as the ball for the next day's game, the twins were able to surreptitiously substitute a squash or a gourd for the ball, retrieving Hunahpu's real head and resulting in an embarrassing defeat for the Xibalbans.

Downfall of Xibalba

Embarrassed by their defeat, the Xibalbans still sought to destroy the twins. They had a great oven constructed and once again summoned the boys, intending to trick them into the oven and to their deaths. The twins realized that the Lords had intended this ruse to be the end of them, but nevertheless, they allowed themselves to be burned in the oven, killed and ground into dust and bones. The Xibalbans were elated at the apparent demise of the twins and cast their remnants into a river. This was, however, a part of the plan devised by the boys, and when cast into the river their bodies regenerated, first as a pair of catfish, and then as a pair of young boys again.

Not recognizing them, the boys were allowed to remain among the Xibalbans. Tales of their transformation from catfish spread, as well as tales of their dances and the way they entertained the people of Xibalba. They performed a number of miracles, setting fire to homes and then bringing them back whole from the ashes, sacrificing one another and rising from the dead. When the Lords of Xibalba heard the tale, they summoned the pair to their court to entertain them, demanding to see such miracles in action.

The boys answered the summons and volunteered to entertain the Lords at no cost. Their identities remained secret for the moment, claiming to be orphans and vagabonds, and the Lords were none the wiser. They went through their gamut of miracles, slaying a dog and bringing it back from the dead, causing the Lords' house to burn around them while the inhabitants were unharmed, and then bringing the house back from the ashes. In a climactic performance, Xbalanque cut Hunahpu apart and offered him as a sacrifice, only to have the older brother rise once again from the dead.

Enthralled by the performance, One Death and Seven Death, the highest lords of Xibalba, demanded that the miracle be performed upon them. The twins obliged by killing and offering the lords as a sacrifice, but did not bring them back from the dead. The twins then shocked the Xibalbans by revealing their identities as Hunahpu and Xbalanque, sons of One Hunahpu whom they had slain years ago along with their uncle Seven Hunahpu. The Xibalbans despaired, confessed to the crimes of killing the brothers years ago, and begged for mercy. As a punishment for their crimes, the realm of Xibalba was no longer to be a place of greatness, and the Xibalbans would no longer receive offerings from the people who walked on the Earth above. All of Xibalba had effectively been defeated.

The twins returned to the ballcourt and retrieved the buried remains of their father, Hun Hunahpu.

Then finished, the pair departed Xibalba and climbed back up to the surface of the Earth. They did not stop there, however, and continued climbing straight on up into the sky. One became the Sun, the other became the Moon.

Hero Twins in other Native American cultures

Many Native American cultures in the United States have traditions of two male hero twins. For instance, in the creation myth of the Navajo (called the Diné Bahaneʼ) the hero twins Monster Slayer and Born for Water (sons of Changing Woman) acquire lightning bolt arrows from their father, the Sun, in order to rid the world of monsters that prey upon the people.

Ho-Chunk and other Siouan-speaking peoples have a tradition of Red Horn's Sons. The mythology of Red Horn and his two sons have some interesting analogies with the Maya Hero Twins mythic cycle.[7]

In popular culture

- Xbalanque is a playable character in the free downloadable PC game Smite, where his title is "The Hidden Jaguar Sun".

- The 2014 From Dusk Till Dawn Series hints at a prophecy about the Gecko Brothers being The "Hero Twins" of Maya legend.

- Hunahpu was the name of one of the tribes in Survivor: San Juan del Sur.

- The Hero Twins appear in the opening of the 2000 animated film The Road to El Dorado. They are also the gods that the main characters Miguel and Tulio impersonate.

See also

- Jaguars in Mesoamerican culture

- Maya religion

- Maya mythology

- Twins in mythology

- Divine twins

- HD 98219

- List of lunar deities

- List of solar deities

Notes

- Coe 2002, p. 75-76

- "See famsi.org for a clearer drawing".

- Coe 1989

- H.E.M. Braakhuis (2009), The Tonsured Maize God and Chicome-Xochitl as Maize Bringers and Culture Heroes, Wayeb Notes No. 32

- "Part 2: Hero Twins". Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-20. Retrieved 2013-05-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Hall, Robert L. (1989), Galloway, Patricia (ed.), "The Cultural Background of Mississippian Symbolism", The Southeastern Ceremonial Complex: Artifacts and Analysis. The Cottonlandia Conference, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, pp. 239–278

References

- Coe, Michael D. (1989). "The Hero Twins: Myth and Image". In Barbara Kerr; Justin Kerr (eds.). The Maya Vase Book: A Corpus of Rollout Photographs of Maya Vases. 1. Justin Kerr (illus.). New York: Kerr Associates. pp. 161–184. ISBN 0-9624208-0-8.

- Las Casas, Bartolomé de (1967) [ca.1559]. Edmundo O'Gorman (ed.). Apologética Historia Sumaria. Serie de historiadores y cronistas de Indias, 1 (in Spanish). 1–2. México D.F.: Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

- Taube, Karl (1997). Aztec and Maya Myths (The Legendary Past) (3rd ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-78130-X.

- Tedlock, Dennis (trans.) (1985). Popol Vuh: the Definitive Edition of the Maya Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-45241-X.

- Thompson, J. Eric S. (1970). Maya History and Religion. Civilization of the American Indian Series, No. 99. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-0884-3.

- Thompson, J. Eric S. (1978). Maya Hieroglyphic Writing; An Introduction. Civilization of the American Indian Series, No. 56 (3rd ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-0958-0.

External links

- The Hero Twins as Catfish, by Justin Kerr, with vase rollout photos

- Diego Rivera, The Trials of the Hero Twins, 1931

- The Hero Twins for kids, with cartoons

- Hero Twins: Explorations of Mythic and Historical Dichotomies, Southern Illinois University Carbondale