Equatoria

Equatoria is a region of southern South Sudan, along the upper reaches of the White Nile. Originally a province of Egypt, it also contained most of northern parts of present-day Uganda, including Lake Albert. It was an idealistic effort to create a model state in the interior of Africa that never consisted of more than a handful of adventurers and soldiers in isolated outposts.[1]

Equatoria | |

|---|---|

Region | |

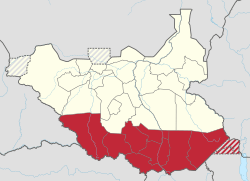

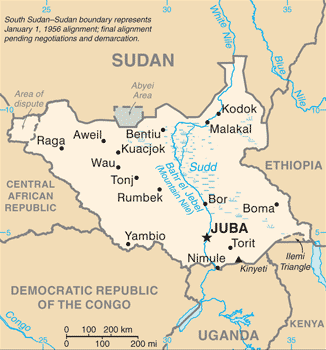

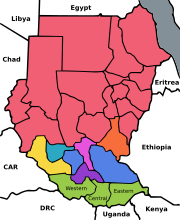

Location in South Sudan | |

| Country | |

| Capital | Juba |

| Area | |

| • Total | 195,847.67 km2 (75,617.21 sq mi) |

| Population (2014 Estimate) | |

| • Total | 3,399,400 |

| • Density | 17/km2 (45/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EAT) |

Equatoria was established by Samuel Baker in 1870. Charles George Gordon took over as governor in 1874, followed by Emin Pasha in 1878. The Mahdist Revolt put an end to Equatoria as an Egyptian outpost in 1889. Later British Governors included Martin Willoughby Parr. Important settlements in Equatoria included Lado, Gondokoro, Dufile and Wadelai. The last two are in the part of Equatoria that is now in Uganda.

Under Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, most of Equatoria became one of the eight original provinces. The state of Bahr el Ghazal was split from Equatoria in 1948. In 1976, Equatoria was further split into the states of East and West Equatoria. The region has been troubled with violence during both the First and Second Sudanese Civil Wars, as well as the anti-Ugandan insurgencies based in Sudan, such as the Lord's Resistance Army and West Nile Bank Front.

Geography

Administrative divisions

Equatoria consists of the following states:

Between October 2015 and February 2020, Equatoria consisted of the following states:

People

.jpg)

The people of Equatoria are traditionally peasants or nomads belonging to numerous ethnic groups. They live in the counties of Budi, Ezo, Juba, Kajo-keji, Kapoeta, Magwi, Maridi, Lainya, Mundri, Terekeka, Tombura, Torit, Yambio, and Yei. Equatoria is inhabited by the ethnolinguistic groups listed below. The following tribes occupy the three states of Greater Equatoria: Acholi, Avokaya, Baka, Balanda, Bari, Didinga, Kakwa, Keliko, Kuku, Lango, Lokoya, Narim, Lopit, Lugbwara, Lulubo, Madi, Makaraka, Moru, Mundari, Mundu, Nyangbwara, Otuho, Pari, Pojulu, Tenet, Toposa and Azande Avukaya Mundu. Some of these tribes like Bari, Pojulu, Kuku, Kakwa, Mundari and Nyangbwara share a common language, but their accents, and some adjectives and nouns do vary; the same applies to Keliko, Moru and Madi.

Languages

Other than Arabic and English, the following languages are spoken in Equatoria according to Ethnologue.[2]

|

|

Culture and music

Due to the many years of the civil war, the culture is heavily influenced by the countries neighboring South Sudan. Many South Sudanese fled to Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Central African Republic, where they interacted with the nationals and learnt their languages and culture. For most of those who remained in the country, or went North to Sudan and Egypt, they greatly assimilated Arabic culture.

Most South Sudanese kept the core of their culture even while in exile and diaspora. Traditional culture is highly upheld and a great focus is given to knowing one's origin and dialect. Although the common languages spoken are Arabi Juba and English, Kiswahili is being introduced to the population to improve the country's relations with its East African neighbors. Many music artists from Equatoria use English, Kiswahili, Arabi Juba (Arabic Creole), their language or dialect or a mix of all. Popular artists sing Afro-beat, R&B, and Zouk. Dynamiq is popular for his reggae.

Early history

In the 19th century, Egypt had control of Sudan and established the Equatoria province to further control its interests over the Nile River. Equatoria was established by British explorer Sir Samuel Baker in 1870. Baker was sent by Egyptian authorities to establish trading posts along the White Nile and Gondokoro (Gondu kuru, means "difficult to dig", in Bari), a trading center located on the east bank of the White Nile in Southern Sudan. Gondokoro was an important center since it was located within a few kilometres from the cutoff point of navigability of the Nile from Khartoum. It is presently located near the city of Juba in Equatoria.

Baker's attempt to create additional trading posts and control Equatoria was unsuccessful because villages surrounding Gondokoro were frequently bypassed by Arab invaders who wanted to impose their culture and way of life on the people. King Gbudwe who ruled Western part of Equatoria at the time as Azande local ruler despised the Arab culture and way of life and encouraged the tribes to resist the invaders and protect their African culture and their way of life. The invaders were met with such stiff resistance from Equatorian tribes such as the Azande, Bari, Lokoya, Otuho, and Pari.

At the end of Baker's service as governor, British general Charles George Gordon was appointed governor of Sudan. Gordon took over in 1874 and administered the region until 1876. He was more successful in creating additional trading posts in the area. In 1876, Gordon's views clashed with those of the Egyptian governor of Khartoum forcing him to go back to London.

In 1878 Gordon was succeeded by the Chief Medical Officer of the Equatoria province, Mehemet Emin, popularly known as Emin Pasha. Emin made his headquarters at Lado (now in South Sudan). Emin Pasha had little influence over the area because the Khartoum governor was uninterested in his development proposals for the Equatoria region.

In 1881, Muhammad Ahmad Abdullah, a Muslim religious leader, proclaimed himself the Mahdi ("expected one") and began a holy war to unify the tribes of Western and Central Sudan, including Equatoria. By 1883 the Mahdists had cut off outside communications. However, Emin Pasha managed to request assistance from Britain via Buganda. The British sent a relief expedition, called the "Advance," in February 1887 to rescue Emin. The Advance navigated up the Congo River and then through the Ituri Forest, one of the most difficult forest routes in Africa, resulting in the loss of two-thirds of the expedition's personnel. While the Advance succeeded in reaching Emin Pasha by February of the following year, the Mahdists had already overrun the bulk of the province, and Emin had already been deposed as governor by his officers in August 1887. The Advance reached the coast, with Emin, by the end of the year, by which point the Mahdists were firmly in control of Equatoria.

In 1898, the Mahdist state was overthrown by the Anglo Egyptian force led by British Field Marshal Lord Kitchener. Sudan was proclaimed a condominium under British-Egyptian administration and Equatoria was administered by the British.

British policy

Equatoria received little attention from the British prior to World War I. Equatoria was closed to outside influences and developed along indigenous lines. As a result, the region remained isolated and underdeveloped. Limited social services to the region were provided by Christian missionaries who opened schools and medical clinics. The education provided by the missionaries was mainly limited to learning English language and arithmetic.

Equatoria and Sudanese independence

In February 1953, the United Kingdom and Egypt reached an agreement providing for Sudanese self-government and self-determination. On January 1, 1956 Sudan gained independence from the British and Egyptian governments. The new state was under the control of the Arab led Khartoum government. The Arab Khartoum government had promised Southerners full participation in the political system, however, after independence the Khartoum government reneged on its promises. Southerners were denied participation in free elections and marginalized from political power. The government actions created resentment in the South that led to a mutiny by a group of Equatorians sparking the 21 year civil war (1955–1972, 1983 to 2004).

Equatoria Corps

Equatorians played an instrumental role in the struggle for autonomy in South Sudan. The origins of Sudan's civil war dates back to 1955, a year before independence, when it became clear the Arabs were going to take over the national government in Khartoum. Equatorians had a military unit called Equatoria Corps, formed during the Anglo-Egyptian administration.

On August 18, 1955, members of the Equatoria Corps mutinied at Torit, Eastern Equatoria.[3] A company of the Equatoria Corps had been ordered to make ready to move to the north, but instead of obeying, the troops mutinied, along with other Southern soldiers across the South in Juba, Yei, Yombo, and Maridi.[4] The Khartoum government sent Sudanese Army forces to quell the rebellion and many mutineers of the Equatoria Corps went into hiding rather than surrender to the Sudanese government. This marked the beginning of the first civil war in southern Sudan. The rebellion that emerged from the Equatoria Corps was later called Anya Nya and the leaders were separatists, who demanded the creation of a separate South Sudan nation, free from Arab domination. The Equatorian leaders of the Anya Nya and founders of the struggle were Saturlino Olire, from Acholi (OBBO), who was the first man said to have fired a bullet, and launched the start of the first civil war, in Torit; Fr. Saturnino Lohure from Otuho; Aggrey Jaden from Pojulu; Joseph Ohide from Otuho; Marko Rume from Kuku; Ezboni Mondiri from Moru; Albino Tombe from Lokoya; Tafeng Lodongi from Otuho; Lazaru Mutek from Otuho; Benjamin Loki from Pojulu; Elia Lupe from Kakwa; Elia Kuzee from Zande;Timon Boro from Moru; Dominic Dabi Manango, from Zande; Alison Monani Magaya, from Zande; Isaiah Paul, from Zande; Dominic Kassiano Dombo, from Zande; and many others.

The Khartoum government sent its forces to arrest the rebels and capture anyone who supported their cause. By the early 1960s civilians believed to be Anya Nya sympathizers were arrested and shipped to Kodok concentration camp where they were tortured and killed. Some of the first detainees and survivors of the horrific torture at Kodok include Emmanuel Lukudu and Philip Lomodong Lako.

By 1969 the Equatorian rebels found support among foreign governments and were able to obtained weapons and supplies. Anya Nya recruits were trained in Israel where they also got some of their weapons. The Anya Nya rebels received financial assistance from Southern Sudanese and Southern exiles from the Middle East, Western Europe, and North America. By the late 1960s, the war had resulted in the deaths of half a million people and several hundred thousand southerners escaped to hide in the forests or to refugee camps in neighboring countries.

Anya Nya controlled the southern countryside while the government forces controlled the major towns in the region. The Anya Nya rebels were small in number and scattered all over the region making their operations ineffective. It is estimated that Anya Nya rebels ranged from 5,000 to 10,000 in number.

On May 25, 1969, Col Gaafar Muhammed Nimeiri led a military coup and overthrew Gen. Ibrahim Abboud's regime. In 1971 Joseph Lagu, from the Madi ethnic group, became the leader of the southern forces opposed to Khartoum government and founded the South Sudan Liberation Movement (SSLM). Anya Nya leaders united and rallied behind Lagu. Lagu also got support for his movement from exiled southern politicians. With Lagu's leadership the SSLM created a governing infrastructure throughout many areas in southern Sudan. In 1972 Nimeri held negotiations with the Anya Nya at Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. At the talks the Anya Nya demanded a separate southern government and an army to defend the south. Ethiopia's Emperor Haile Selassie moderated the talks and helped the two sides reach an agreement. The result was the Addis Ababa Agreement. The Addis Ababa Accords granted autonomy for the South with three provinces: Equatoria, Bar al Ghazal and Upper Nile. The south would have a regional president appointed by the national president to oversee all aspects of government in the region. The national government would maintain authority over defense, foreign affairs, currency, and finance, and economic and social planning, and interregional concerns. The members of the Anya Nya would be incorporated into the Sudanese army and have equal status with the northern forces. The accord declared Arabic as Sudan 's official language and English as the south's principal language for administration and schooling. Despite opposition from SSLM leaders on the terms of the Agreement, Joseph Lagu approved the agreement and both sides agreed to a cease-fire. The Addis Ababa Accords were signed on March 27, 1972 and the Sudanese celebrated that day as National Unity Day. This agreement resulted in a hiatus in the Sudanese civil war from 1972 to 1983.

Recent history

In 1983, President Gaafar Nimeiry abolished the parliament and embarked on a campaign to Islamize all of Sudan. He outlawed political parties and enacted Sharia law in the penal code. Non-Muslim southerners were now forced to obey Islamic laws and traditions. The policies revived southern opposition and military insurgency in the South. In 1985 Abdel Rahman Swar al-Dahab led a coup and overthrew the regime. In 1986, Sadiq al-Mahdi was elected president of Sudan. The new regime began negotiations led by Colonel John Garang de Mabior, the leader of the Sala, but failed to reach an agreement to end the southern insurgency. Civil war has continued since then, but international pressure has led SPLA and the Khartoum government to reach an agreement to end the 21-year civil war.

References

- Moorehead, Alan (2000). The White Nile (First ed.). New York: Harper Perennial. p. 448. ISBN 978-0060956394. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- Languages of South Sudan. Ethnologue, 22nd edition.

- Robert O. Collins, Civil wars and revolution in the Sudan: essays on the Sudan, 2005, p.140

- O'Ballance, 1977, p.41

- R. Gray, A History of the Southern Sudan, 1839–1889 (London, 1961).

- Iain R. Smith, The Emin Pasha Relief Expedition 1886–1890 (Oxford University Press, 1972).

- Alice Moore-Harell, Egypt's African Empire: Samuel Baker, Charles Gordon and the Creation of Equatoria (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2010).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Equatoria. |