Sonnet 53

Shakespeare's Sonnet 53, presumably addressed to the same young man as the other sonnets in the first part of the sequence, raises some of the most common themes of the sonnet: the sublime beauty of the beloved, the weight of tradition, and the nature and extent of art's power. As in Sonnet 20, the beloved's beauty is compared to both a man's (Adonis) and a woman's (Helen).

| Sonnet 53 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

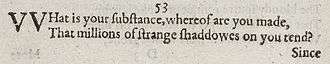

The first two lines of Sonnet 53 in the 1690 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Structure

Sonnet 53 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The Shakespearean sonnet contains three quatrains followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the typical rhyme scheme of this form, abab cdcd efef gg and is composed in a type of poetic metre called iambic pentameter based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The seventh line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / On Helen's cheek all art of beauty set, (53.7)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

Source and analysis

Following George Wyndham, John Bernard notes the neoplatonic underpinnings of the poem, which derive ultimately from Petrarch: the beloved's transcendent beauty is variously diffused through the natural world, but is purer at its source. The reference to Adonis has led numerous scholars, among them Georg Gottfried Gervinus, to explore connections to Venus and Adonis; Gerald Massey notes that the twinned references to Adonis and Helen underscore the sense of the beloved's androgyny, most famously delineated in Sonnet 20. Hermann Isaac notes that the first quatrain resembles a sonnet by Tasso. In support of his hypothesis that the person addressed in the sonnet was an actor, Oscar Wilde hypothesized that the poem's "shadows" refer to the young man's roles.

The poem is comparatively free of cruces. "Tires" (l. 8), which generally refers only to a head dress, has been glossed by editors from Edward Dowden to Sidney Lee as referring to the entire outfit. "Foison," a word of French origin, relatively uncommon even in Shakespeare's time, is glossed by Edmond Malone as "abundance."

The placement of the sonnet in the sequence has also caused some confusion. The last line, which is not evidently sarcastic, appears to contradict the tone of betrayal and reproach of many of the closest neighboring sonnets in the sequence as first presented.

A dominant motif within the first two stanzas of Sonnet 53 is the contrast between shadow and substance. According to G.L. Kittridge, in Sonnets of Shakespeare, "Shadow, often in Shakespeare is contrasted with substance to express the particular sort of unreality while 'substance' expresses the reality." The shadow is that which cannot be expressed in a concrete manner while substance is that which is tangible. Kittridge goes into more detail about the use of shadow and couplet within the initial couplet. "Shadow is the silhouette formed by a body that intercepts the sun's rays; a picture, reflection, or symbol. "Tend" means attend, follow as a servant, and is strictly appropriate to 'shadow' only in the first sense, though shadows is used here in the second… All men have one shadow each in the first sense; you being only one can yet cast many shadows, in the second sense, for everything good or beautiful is either a representation of you or a symbol of your merits," (Sonnets, p. 142). This definition helps elaborate on Shakespeare's extended metaphor and wordplay, explaining that shadow is that which is not palpable as well as the reflection of the young man in all that is real. Jonathan Bate, in his work, The Genius of Shakespeare, analyzes the classical allusions within the poem. He writes, "In Sonnet 53, the youth becomes Adonis, retaining a controlling classical myth beneath the surface,' (Genius, p. 48). In addition, Bate writes about how the poem could be interpreted in a way reminiscent of Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, "In A Midsummer Night's Dream, Theseus says that lunatics, lovers, and poets are of imagination all compact- their mental states lead to kinds of transformed vision whereby they see the world differently from how one sees it when in a 'rational' state of mind," (Bate, p. 51). This quote draws upon the theme of Shakespeare's attempt to materialize intangible emotions such as love or an aesthetic appreciation for beauty. Shakespearean scholar Joel Fineman offers a criticism of Shakespeare's sonnets in a broader context that is evident in Sonnet 53. Fineman writes, "from Aristotle on the conventional understanding of rhetoric of praise as all the rhetoricians uniformly say, energetically, 'heightens its effect," (Fineman). In this sense, the praise of the young man is meant to highlight his features and bring them to a literal understanding.

The first line of the third quatrain extends the conceit of the Platonic theory, the idea that the perceptions of reality are merely reflections of the essential reality of forms. Platonic theory suggests that our perceptions are derived from this world of forms in the same way shadows are derived from the objects that are lit. The metaphor of shadow was often employed to help explain the illusory quality of perception and the reality of forms, both by Renaissance Platonists and by Plato himself in his book, Symposium.[2] In the sonnet, spring can only offers shades of the beauty of the youth. The youth is presented as the ideal Beauty, the form, from which all other beautiful things come.[3] This idea is summarized in line thirteen of the sonnet: "In all external grace you have some part." This line finds the youth to be the exclusive source of all beautiful things, expanding his "domain" even further than the first quatrains in which the youth is said to be the source of the legendary figures of Adonis and Helen.

Scholars though have disagreements about the end for which the Platonic theory is used. In "the usual interpretation of an elliptical construction," the ending couplet expresses further praise for the youth, seeming to say that while all things beautiful are shades of the youth, the youth like nothing else, is distinguished by a constant, faithful heart.[4] Considering the sonnets expressing betrayal in Sonnets 40-42, this sonnet extolling the youth's constancy seems absurd for some scholars and is problematic. Seymour-Smith suggests that the last line should be interpreted: "you feel affection for no one, and no one admires you for the virtue of constancy".[5] Duncan Jones agrees and suggests that the word "but" at the beginning of the closing line radically changes all that has gone before and marks a turn to a more critical perspective.

One interpretation of the sonnet by Hilton Landry interprets the last line in a slightly different light. He proposes that Sonnet 53 is part of a tentative group stretching from Sonnet 43 to Sonnet 58 which have in common the speaker's separation from the youth. Sonnet 53 in itself makes no mention of absence from the youth, but connects to this larger group via similar themes and word choices. Landry points out that seven other poems, sonnets 27, 37, 43, 61, 98, 99, and 113, connect separation with images of shadows. He notes that it is only when the speaker is absent from his friend that he begins to speak of shadows and images. Separation, Landry says, causes the poet's imagination to begin, "to find, or rather project, many images of the friend's beauty in his surroundings".[6]

In light of the poem's situation within the group of sonnets expressing separation from the youth and the feelings of betrayal seen in Sonnet 35 and 40-42, Landry argues that the speaker in the last line praises the youth's fidelity not because he is confident of the youth's constancy but because he fitfully hopes that the youth will have a constant heart.[7] Putting it another way, the speaker hopes that by praising the youth for his constancy the youth will become more constant while the pair is separated. This style of cautious advice finds parallels in Renaissance rhetoric. Francis Bacon in his essay, "Of Praise", explains a particular method of addressing kings and great persons with civility in which, "by telling men what they are, they represent to them what they should be".[8] In addition, C.S. Lewis notes that an established feature of praise verse in the Renaissance was that it, "hid advice as flattery and recommended virtues by feigning that they already existed".[9]

Helen Vendler, writing in The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets, is in agreement with Landry that the closing line is largely propitiatory though she arrives at this conclusion without including Sonnet 53 within a group of separation sonnets. She notes that the youth having, "millions of adorers…hover about him together with his millions of seductive shadows," and an androgynous beauty, as comparable to Adonis as Helen, that doubles the number of potential admirers puts the youth in a particularly dangerous situation to give in to temptation.[10]

Cultural references

Anthony Hecht's third book of poetry is titled Millions of Strange Shadows in reference to the second line.

Notes

- Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. Shakespeare's Sonnets with Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2007. 148-149. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. Shakespeare's Sonnets with Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2007. 148-149. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. Shakespeare's Sonnets with Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2007. 148-149. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. Shakespeare's Sonnets with Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2007. 148-149.ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7

- (Landry, Hilton. Interpretations in Shakespeare's Sonnets: The Art of Mutual Render. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1963. 47-55. OCLC # 608824

- Landry, Hilton. Interpretations in Shakespeare's Sonnets: The Art of Mutual Render. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1963. 47-55. OCLC # 608824

- Landry, Hilton. Interpretations in Shakespeare's Sonnets: The Art of Mutual Render. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1963. 47-55. OCLC # 608824

- Landry, Hilton. Interpretations in Shakespeare's Sonnets: The Art of Mutual Render. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1963. 47-55. OCLC # 608824

- Vendler, Helen. The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge and London: Belknap-Harvard University Press, 1997. 258-260. OCLC # 36806589

References

- Baldwin, T. W. On the Literary Genetics of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1950.

- Bate, Jonathan, The Genius of Shakespeare, 1998.

- Bernard, John. "'To Constancie Confin'd': the Poetics of Shakespeare's Sonnets." PMLA 94 (1979): 77-90.

- Fineman, Joel. Shakespeare's Perjured Eye: the Invention of Poetic Subjectivity in the Sonnets, 1986. OCLC 798792423 ISBN 9780520054868

- Hubler, Edwin. The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952.

- Kittridge, G.L.Sonnets of Shakespeare.

- Landry, Hilton. Interpretations in Shakespeare's Sonnets. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1963. 47-55. OCLC # 608824

- First edition and facsimile

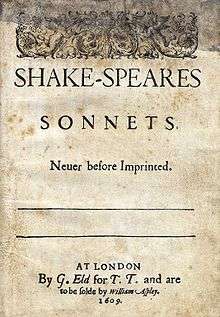

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

.png)