Sonnet 11

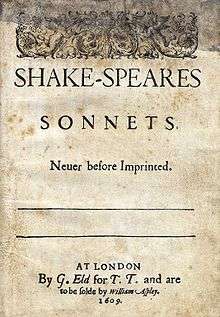

Sonnet 11 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a procreation sonnet within the 126 sonnets of the Fair Youth sequence, a grouping of Shakespeare's sonnets addressed to an unknown young man. While the order in which the sonnets were composed is undetermined (though it is mostly agreed that they were not written in the order in which modern readers know them), Sonnet 11 was first published in a collection, the Quarto, alongside Shakespeare's other sonnets in 1609.[2]

| Sonnet 11 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Sonnet 11 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

In the sonnet, the speaker reasons that though the young man will age his beauty will never fade so long as he passes his beauty on to a child. The speaker insists it is nature's will that someone of his beauty should procreate and make a copy of himself, going so far as to comment on the foolish effects of ignoring the necessity and inevitability of such procreation upon both the youth and mankind.

Synopsis

Sonnet 11 is part of the first block of 17 sonnets in the Fair Youth sequence (sonnets 1–126) and describes Shakespeare's call for the preservation of the Youth's beauty through procreation. Shakespeare urges the Fair Youth to copulate with a woman in marriage and conceive a boy so that the child may inherit and preserve the beauty of the Fair Youth. For, Shakespeare reasons, in fathering a child, the Youth can keep himself in youth and tenderness, as he has created another copy of himself to attested to the loveliness he loses as he ages.[3] Then in further manipulating the Youth to this idea, Shakespeare delves into what about the Fair Youth is worth preserving. Namely everything, as "Nature gave abundantly to those whom she endowed with the best qualities" (paraphrase, lines 11–12), flattering the Youth while showing his waste in not complying to "print more".[4]

Structure

Sonnet 11 is composed in the traditional form of what has come to be called the "Shakespearean" sonnet, also known as a "Surreyan" or "English" sonnet. The form, having evolved from the "Petrarchan" sonnet (originated in the thirteenth or fourteenth century by Italian poet Francesco Petrarch), entered the style as Shakespeare would have known it within the works of sixteenth century English poets the Earl of Surrey and Sir Thomas Wyatt. However, as it came to be the most popular sonnet form with which Shakespeare wrote his poetry, it took on his name.[5]

An English sonnet is made up of fourteen lines grouped into three quatrains and an ending couplet, with the rhyme scheme ABAB CDCD EFEF GG. Sonnet 11 exhibits this structure.

The sonnet has four feminine endings (accepting the Quarto's contraction of "grow'st" and "bestow'st"). "Convertest" would have been pronounced as a perfect rhyme with the second line's "departest", a holdover from Medieval English.[6] Carl D. Atkins notes "This is a sonnet of contrasts: feminine lines, regular lines; regular iambs, irregular line 10; no midline pauses, multiple midline pauses; waning, growth, beauty, harshness, life and death, beginning and end."[7]

This sonnet, like all but one of Shakespeare's sonnets, employs iambic pentameter throughout. The first line can be scanned as a regular iambic pentameter.

× / × / × / × / × / As fast as thou shalt wane, so fast thou grow'st (11.1)

The tenth-line irregularity alluded to by Atkins consists of two quite ordinary pentameter variations: a midline reversal, and a final extrametrical syllable (or feminine ending). However, their coincidence, together with their context, makes them stand out:

× / × / × / / × × /(×) Harsh, featureless, and rude, barrenly perish: (11.10)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus. (×) = extrametrical syllable.

While the beginning of the line is metrically regular, its initial nonictic stress and multiple syntactic breaks nevertheless give it a sense of roughness. The midline reversal and feminine ending together impart an abrupt falling rhythm on the end of the line, as though the phrase was brutally grafted on. "The line seems to describe itself."[7]

Context and Analysis

Since the sonnets' first publication a debate has raged as to the identity of the Fair Youth to whom so many of Shakespeare's sonnets are addressed. The most common theory is a Mr. W.H. And still even among this theory scholars have been unable to agree upon which persons should claim the title of Mr. W.H. The four main contenders, presented as such by Kenneth Muir in Shakespeare's Sonnets, are: "Apart from some candidates too absurd to merit discussion- William Himself, Willie Hughes- there are four main contenders: William Harvey, William Hatcliffe, William Hervert and Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton".[8] Out of these four, Henry Wriothesley is one of the favorites, as Shakespeare had dedicated two of his narrative poems to the Earl. Muir had another idea that, "It is, of course possible that the Sonnets were inspired by Shakespeare's relationship with more than one patron ... but, if so, this would undercut the poet's vows of eternal fidelity. It is possible, too, that W.H. has not yet been identified; and it is possible that there is such a large admixture of fiction in the sonnet story that it is a waste of time to treat them as contributions to the biography of any of the four candidates."

Whatever his identity, scholars and literati alike can conclude that the author was in love with the younger man. "However much we shuffle the pack, we have the same basic facts: that the poet loved a younger man, probably of aristocratic birth; that he urged him to marry and then claimed that he would immortalize him in his verse".[9]

As scholars are continuously adjusting their arguments as to who the Fair Youth may truly be, pinpointing the exact time of the text's composition prior to publication is difficult. The time-frame changes drastically depending upon the Youth's identity, and even the very order of the sonnets is questioned within the context of who the Fair Youth must have been. Regardless of the date and order of their composition though, scholars have been able to determine that, "It is true that the first seventeen, in which the poet is urging his friend to marry in order to perpetuate his beauty, have a thematic unity", making sonnet 11, if nothing else, a part of this subgroup of 17 known as the procreation sonnets.[8]

The procreation sonnets group sonnets 1–17 together, some claiming that they could very well be joined together as a single poem. They feed off of one other and Muir says, "The first seventeen, sonnets, urging the young man to marry so as to perpetuate his beauty, employ, as we have seen, traditional arguments in favour of marriage - some of the imagery ... These sonnets are closely linked by the repetition of rhymes in adjacent, or nearly adjacent, poems". Sonnet 11 is clearly apart of the marriage theme and the implications it speaks of nature gifting the Youth with, "Wisdom, beauty and increase". The Poet goes on to add that it would be 'folly' for the Youth not to have a child to which he could pass off these traits.[10]

Shakespeare famed for his mastery of wordplay and double-meaning, such as in Sonnet 11's opening line, "As fast as thou shalt wane so fast thou grow'st." This echoes the maxim, "Youth waineth by increasing," an aside of the elderly, with which Shakespeare will conclude his series of sonnets to the young man at Sonnet 126. It has been associated with Narcissus who wasted away as he grew as a youth. Here the aphorism is used allusively to argue for procreation.[11] Narcissus is mentioned by Muir as similar to the Procreation sonnets, in that both the Fair Youth and Narcissus are obsessed with their own self beauty and how such beauty would easily be lost were they not to procreate.[12]

Exegesis

Sonnet 11 has been compartmentalized as being part of the Fair Youth section (sonnets 1–126) of Shakespeare's 154 sonnets. Shakespeare's main objective in this sonnet is to manipulate the Youth into preserving his beauty. The Poet pushed the message that the boy should marry a woman and have a child, so that the Fair Youth could stay young in the tender form of the Youth's own son.[3]

Quatrain 1

As fast as thou shalt wane, so fast thou grow'st

In one of thine, from that which thou departest;

And that fresh blood which youngly thou bestow'st

Thou mayst call thine, when thou from youth convertest;[13]

Sonnet 11 begins with calling out the Youth on his slow decline in beauty. To paraphrased the first two lines, "As fast as you decline in beauty, so in your child you grow into that beauty which you yourself leave behind". This is also the beginning of the speaker's push for the Youth to have a child within this particular sonnet.[4] William Rolfe takes these same two lines and rolls out a thicker interpretation. He explains that having children explored how no matter how fast a person increases in age; the youth the young man has lost will be placed into his offspring. Rolfe ends his description by saying, "As it were, growing afresh that which thou departest (to depart) from".[14] This verse truly sets the stage for what the speaker wishes to convey most to the fair youth. Katherine Duncan-Jones expands that by paraphrasing the speaker's meaning behind line 3, saying, "You give your blood (semen) to a wife while you are young, and, perhaps, in a youthful manner".[13] The speaker has found every way to push at the idea of the Fair Youth marrying and having children.

Quatrain 2

Herein lies wisdom, beauty and increase;

Without this, folly, age and cold decay;

If all were minded so, the times should cease,

And threescore year would make the world away:[13]

The second quatrain (lines 5–8) warns the Youth of the negative effects the refusal to procreate would have on mankind, how if everyone thought/refused as the Youth did, "were minded so," humans would die off within "threescore year" (three generation, or sixty or so years in Shakespeare's time).[13]

Opening this quatrain, line 5 begins with 'Herein,' alluding to the concept of marriage and procreation which 'herein' possess the virtues of 'wisdom, beauty, and increase'.[13] In contrast not following this "plan" of procreation leads to 'folly, age and cold decay' of both the Youth (having no child 'herein' to carry on his expiring "virtue and virility") and humankind.[6] With the phrase 'minded so' in line 7 the speaker is referring to those who hold "the same opinion as you [the Youth]," with 'minded' referring to an opinion, thought or belief; in this case someone who holds the same position as the Youth.[13] 'The times' in line 7 refers to "the human era"[13] or "generations" as it was common for Shakespeare to use 'time' to encompass someone's lifespan.[6] As mentioned earlier, 'threescore year' is three generations, roughly sixty years, in Shakespeare's time, with 'make the world away' expanding on the phrase to "make away" meaning to "put an end to" or "destroy".[13] In line 8, 'year' is akin to the plural 'years' and while the statement 'the world' simply stands for the world "of men" it can read as a hyperbole, extending the end of the world of man to the end of "everything on earth" or in everything "the cosmos".[6]

Quatrain 3

Let those whom nature hath not made for store,

Harsh, featureless and rude, barrenly perish;

Look whom she best endowed, she gave the more,

Which bounteous gift thou shouldst in bounty cherish:[13]

Quatrain 3 takes on a slightly different path in addressing to the Youth. It speaks of nature and how she gave more to those who already had so much and little to those who already had nothing (this example can be found in the Synopsis). As definitions of certain words have changed from their meanings in the sixteenth century, an explanation of their original content is needed to understand quatrain 3 in its entirety. One of these words is 'store', which Hammond points out that within the context of the line means, "The breeding of animals". This supports the theme of the sonnet in its wish of the Youth to have a child.[4] Another expansion on this quatrain further explores nature giving more to those whom she's already gifted and how John Kerrigan sees this as being similar to Matthew's paradox in Matt. 25:29 (Bible verse). The comparison comes from the line saying, "For unto everyone that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance: But he that hath not, from him shall be taken away, even that which he hath". Kerrigan finds that line 11 is a good shadow of this line from Mathew (New Testament).[6] This quatrain is able to bring out the sort of beliefs in the idea of beauty and power in the time of Shakespeare.

Couplet

She carved thee for her seal, and meant thereby

Thou shouldst print more, not let that copy die.[13]

The couplet of a sonnet often serves one of three purposes: to offer a reason to confirm what has gone before, to follow through and complete the current idea, or to contradict or modify the quatrains.[2] The closing couplet (lines 13–14) is meant to drive home the speaker's message that the Youth must spawn a child, as nature herself willed him to "print more" rather than see him, the original "copy" die, his beauty lost.

Beginning line 13 is "She carved thee for her seal." Here 'She' refers to 'nature' (personified as to be mother nature) mentioned in line 8, while 'seal,' refers to "the stamp ... which represents nature's authority"[13] or a mark which "displays authority" rather than the closing of something or the physical wax itself. The Youth is a display of what it looks like to be of nature's "best endowed" (line 11) and "shows the world what nature is and can do."[6] In line 14 the call to "print more" does not mean necessarily to make an exact 'copy' or clone of the Youth with the best nature can bestow but rather, simply another person. In this case a child, who also displays and/or possess the 'seal' of nature.[13] The word 'copy,' also in line 14, one scholar notes, refers to a "pattern" or something "capable of producing copies"[6] as, "in sixteenth-century English, a 'copy' was something from which copies were produced."[15] Moreover, in Golding's translation it is argued that here Shakespeare uses the language of stone and carving, echoing the story of the creation of man from Ovid. Nature has "caru'd" out the youth so that he is no longer a rudely shaped impression in stone. He is a perfectly shaped, featured figure, which nature has carved. Here the translator finds a play on the word 'die' in that nature made this wonderful 'copy' intending that the Youth should stamp further copies ("should'st print more"), not stand alone like an unused die that can only die ("not let that copy die").[11] The word 'copy' is also a play on the Latin copia meaning abundance.[13]

Notes

- Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- Muir 1979.

- Matz 2008, p. 78.

- Hammond 2012, p. 130.

- Matz 2008, pp. 21–27.

- Kerrigan 1995, pp. 186–187.

- Atkins 2007, p. 52.

- Muir 1979, pp. 1–7.

- Muir 1979, pp. 6–7.

- Muir 1979, pp. 45–52.

- Larsen, Kenneth J. "Sonnet 11". Essays on Shakespeare's Sonnets. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- Muir 1979, pp. 46–47.

- Duncan-Jones 2010, pp. 132–133.

- J. Rolfe, William (1905). Shakespeare's Sonnets. New York, Cincinnati and Chicago: American Book Company. p. 149.

- Kerrigan 1995, pp. 27–28.

References

- Hammond, Paul (2012). Shakespeare's sonnets: an original-spelling text. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-964207-6. OCLC 778269717.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Matz, Robert (2008). The world of Shakespeare's sonnets : an introduction. North Carolina: Mcfarland and Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-3219-6. OCLC 171152635.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Muir, Kenneth (1979). Shakespeare's Sonnets. Unwin Critical Library. London: George Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-04-821042-0. OCLC 5862388.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

External links

- Paraphrase of sonnet in modern language

- Analysis of the sonnet

.png)