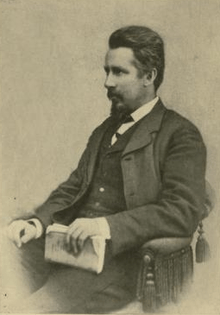

Edward Dowden

Edward Dowden (3 May 1843 – 4 April 1913), was an Irish critic and poet.

Biography

He was the son of John Wheeler Dowden, a merchant and landowner, and was born at Cork, three years after his brother John, who became Bishop of Edinburgh in 1886. Edward's literary tastes emerged early, in a series of essays written at the age of twelve. His home education continued at Queen's College, Cork and at Trinity College, Dublin; at the latter he had a distinguished career, becoming president of the Philosophical Society, and winning the vice-chancellor's prize for English verse and prose, and the first senior moderatorship in ethics and logic. In 1867 he was elected professor of oratory and English literature in Dublin University.[1]

Dowden's first book, Shakspere: A Critical Study of His Mind and Art (1875), resulted from a revision of a course of lectures, and made him widely known as a critic: translations appeared in German and Russian; his Poems (1876) went into a second edition. His Shakespeare Primer (1877) was translated into Italian and German. In 1878 the Royal Irish Academy awarded him the Cunningham gold medal "for his literary writings, especially in the field of Shakespearian criticism."[1][2]

Later works by him in this field included an edition of The Sonnets of William Shakespeare (1881), Passionate Pilgrim (1883), Introduction to Shakespeare (1893), Hamlet (1899), Romeo and Juliet (1900), Cymbeline (1903), and an article entitled "Shakespeare as a Man of Science" (in the National Review, July 1902), which criticized T. E. Webb's Mystery of William Shakespeare. His critical essays "Studies in Literature" (1878), "Transcripts and Studies" (1888), "New Studies in Literature" (1895) showed a profound knowledge of the currents and tendencies of thought in various ages and countries; but his The Life of Percy Bysshe Shelley (1886)[3][4] made him best known to the public at large. In 1900 he edited an edition of Shelley's works.[1]

Other books by him which indicate his interests in literature include: Southey (in the "English Men of Letters" series, 1879), his edition of Southey's Correspondence with Caroline Bowles (1881), and Select Poems of Southey (1895), his Correspondence of Sir Henry Taylor (1888), his edition of Wordsworth's Poetical Works (1892) and of his Lyrical Ballads (1890), his French Revolution and English Literature (1897; lectures given at Princeton University in 1896), History of French Literature (1897), Puritan and Anglican (1900), Robert Browning (1904) and Michel de Montaigne (1905). His devotion to Goethe led to his succeeding Max Müller in 1888 as president of the English Goethe Society.[1]

In 1889 he gave the first annual Taylorian Lecture at the University of Oxford, and from 1892 to 1896 served as Clark lecturer at Trinity College, Cambridge. To his research are due, among other matters of literary interest, the first account of Thomas Carlyle's Lectures on periods of European culture; the identification of Shelley as the author of a review (in The Critical Review of December 1814) of a romance by Thomas Jefferson Hogg; a description of Shelley's Philosophical View of Reform; a manuscript diary of Fabre d'Églantine; and a record by Dr Wilhelm Weissenborn of Goethe's last days and death. He also discovered a Narrative of a Prisoner of War under Napoleon (published in Blackwood's Magazine), an unknown pamphlet by Bishop Berkeley, some unpublished writings of William Hayley relating to Cowper, and a unique copy of the Tales of Terror.[5]

His wide interests and scholarly methods made his influence on criticism both sound and stimulating, and his own ideals are well described in his essay on The Interpretation of Literature in his Transcripts and Studies. As commissioner of education in Ireland (1896–1901), trustee of the National Library of Ireland, secretary of the Irish Liberal Union and vice-president of the Irish Unionist Alliance, he enforced his view that literature should not be divorced from practical life.[6] His biographical/critical concepts, particularly in connection with Shakespeare, are played with by Stephen Dedalus in the library chapter of James Joyce's Ulysses. Leslie Fiedler was to play with them again in The Stranger in Shakespeare.

Dowden married twice, first (1866) Mary Clerke, and secondly (1895) Elizabeth Dickinson West, daughter of the dean of St Patrick's.[6] His daughter by his first wife, Hester Dowden, was a well-known spiritualist medium.

Edward Dowden died in Dublin. His Letters were published in 1914 by Elizabeth and Hilda Dowden.[7][8]

References

- Chisholm 1911, p. 456.

- "Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, 1878". Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- Dowden, Edward (1886). The Life of Percy Bysshe Shelley.

- "Review of The Life of Percy Bysshe Shelley by Edward Dowden". The Quarterly Review. 164: 285–321. April 1887.

- Chisholm 1911, pp. 456–457.

- Chisholm 1911, p. 457.

-

- Dowden, E.; Dowden, E.D.W.; Dowden, H.M. (1914). Letters of Edward Dowden and his correspondents. J. M. Dent & Sons, Ltd. Retrieved 2019-08-07.

- Dowden, Edward. (1875). Shakespeare: A Critical Study of his Mind and Art. Henry S. King & Co. (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2009; ISBN 978-1-108-00076-5)

Further reading

- William M. Murphy. "Prodigal Father: the Life of John Butler Yeats (1839–1922)" (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1978; paperback edition, 1979; revised paperback edition, Syracuse University Press, 2001.)

- William M. Murphy, 'Yeats, Quinn, and Edward Dowden,' in "John Quinn: Selected Irish Writers from His Library," ed. Janis and Richard Londraville (Locust Hill Press, 2001).

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Edward Dowden |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edward Dowden. |

- Works by Edward Dowden at Project Gutenberg

- In Defense of Harriet Shelley – comments on Dowden's Life of Shelley by Mark Twain

- Works by or about Edward Dowden at Internet Archive

- Works by Edward Dowden at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "Archival material relating to Edward Dowden". UK National Archives.