Sonnet 93

Sonnet 93 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a member of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man.

| Sonnet 93 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

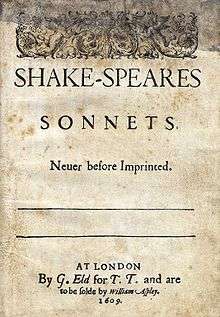

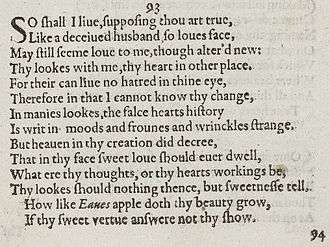

Sonnet 93 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Synopsis

Continuing the alarmed discovery at the end of Sonnet 92, the poet here explores what it would be like to be living a life in which the young man's deceiving of him is simply unknown to the poet. Instead of dying at the moment of discovery of falsity, the poet now lives 'like a deceived husband'.

The vocabulary of this sonnet repeats terms that appear throughout the sequence, and gives readers a sense of the sequence feeding off itself, finding source in its own prior utterances.

Sonnet 93 features 'face' twice (15 times in the whole sequence), 'looks' twice (12 times in the whole sequence), and 'love' also twice ('love', unsurprisingly appears frequently, 172 times, throughout the Q1609 sequence).

Remarkably, the poet imagines himself as being like a 'deceived husband': directly relating his friendship with the young man to marriage. The sonnet ends with the allusion to 'Eve's apple', making the 'deceived husband', the poet in line 2, into a version of Adam, and the betrayal into a version of the Fall. Otherwise, religious references in the poem seem facile or inflated: 'heaven in thy creation did decree' etc. Readers are confronted again to the exaggerated sense of betrayal expressed in these sonnets - what kind of claim could the poet have thought he had over the young man?

The final line of the sonnet expresses the poet's uneasy bafflement: the young man's beautiful 'show' is completely opaque, he will only ever seem beautiful to the poet, his heart's duplicitous inner 'workings' will never betray themselves in 'moods and frowns and wrinkles strange'. That triad of terms, redundant in expression again suggests that Shakespeare in not writing at high pressure in this sonnet. 'Workings' is a rare word in Shakespeare, only here and in the no doubt near contemporary Henry IV Part 2. The unreadable, always beautiful face of the young man looks forward in the Q1609 sequence to the face of the 'woman coloured ill' in the final group of so-called 'Dark Lady' sonnets, where face and deeds match blackness, rather than the young man's mismatch of lovely appearance and morally ugly behaviour.

This sonnet perhaps struggles to get the attention of experienced readers of the sequence, as it is followed by a far more striking sonnet, 94, and such readers might always be tempted to turn to the utterly unformulaic sonnet that follows.

Structure

Sonnet 93 is notionally an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet has three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. However, in terms of its syntactical units, sonnet 93 breaks down into 6 lines, another 6, then the closing couplet. It still follows the typical rhyme scheme of the form, ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, and is composed in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The 5th line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / For there can live no hatred in thine eye, (93.5)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

The meter demands a few variant pronunciations: line 2's "deceivèd" has three syllables,[2] and line 9's "heaven" functions as one.[3]

Notes

- Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- Kerrigan 1995, p. 123.

- Kerrigan 1995, p. 290.

References

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

.png)