Sonnet 22

Sonnet 22 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare, and is a part of the Fair Youth sequence.

| Sonnet 22 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

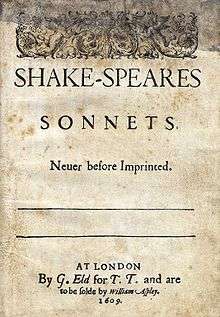

Sonnet 22 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

In the sonnet, the speaker of the poem and a young man are represented as enjoying a healthy and positive relationship. The last line, however, hints at the speaker's doubts, which becomes prominent later in the sequence.

Synopsis

Sonnet 22 uses the image of mirrors to argue about age and its effects. The poet will not be persuaded he himself is old as long as the young man retains his youth. On the other hand, when the time comes that he sees furrows or sorrows on the youth's brow, then he will contemplate the fact ("look") that he must pay his debt to death ("death my days should expiate"). The youth's outer beauty, that which 'covers' him, is but a proper garment ("seemly raiment") dressing the poet's heart. His heart thus lives in the youth's breast as the youth's heart lives in his: the hearts being one, no difference of age is possible ("How can I then be elder than thou art?").[2]

The poet admonishes the youth to be cautious. He will carry about the youth's heart ("Bearing thy heart") and protect ("keep") it; "chary" is an adverbial usage and means 'carefully'. The couplet is cautionary and conventional: when the poet's heart is slain, then the youth should not take for granted ("presume") that his own heart, dressed as it is in the poet's, will be restored: "Thou gav'st me thine not to give back again."[2]

Structure

Sonnet 22 is a typical English or Shakespeare sonnet. Shakespearean sonnets consists of three quatrains followed by a couplet, and follow the form's rhyme scheme: ABAB CDCD EFEF GG. They are written in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions per line. The first line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / My glass shall not persuade me I am old, (22.1)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus. (×) = extrametrical syllable.

The eleventh line exhibits two common metrical variations: an initial reversal, and a final extrametrical syllable or feminine ending:

/ × × / × / × / × /(×) Bearing thy heart, which I will keep so chary (22.11)

Source and analysis

The poem is built on two conventional subjects for Elizabethan sonneteers. The notion of the exchange of hearts was popularized by Petrarch's Sonnet 48; instances may be found in Philip Sidney (Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia) and others, but the idea is also proverbial. The conceit of love as an escape for an aged speaker is no less conventional and is more narrowly attributable to Petrarch's Sonnet 143. The image cannot be used to date the sonnet, if you agree with most critics, that it was written by a poet in his mid-30s. Samuel Daniel employs the same concept in a poem written when Shakespeare was 29, and Michael Drayton used it when he was only 31. Stephen Booth perceives an echo of the Anglican marriage service in the phrasing of the couplet.

"Expiate" in line 4 formerly caused some confusion, since the context does not seem to include a need for atonement. George Steevens suggested "expirate"; however, Edmond Malone and others have established that expiate here means "fill up the measure of my days" or simply "use up." Certain critics, among them Booth and William Kerrigan, still perceive an echo of the dominant meaning.

The conventional nature of the poem, what Evelyn Simpson called its "frigid conceit," is perhaps a large part of the reason that this poem is not among the most famous of the sonnets today.

References

- Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- Larsen, Kenneth J. "Sonnet 22". Essays on Shakespeare's Sonnets. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

Sources

- Baldwin, T. W. (1950). On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

- Hubler, Edwin (1952). The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Schoenfeldt, Michael (2007). The Sonnets: The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's Poetry. Patrick Cheney, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

External links

- Paraphrase and analysis (Shakespeare-online)

- Analysis

.png)