Sonnet 14

Sonnet 14 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a procreation sonnet within the Fair Youth sequence.

| Sonnet 14 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

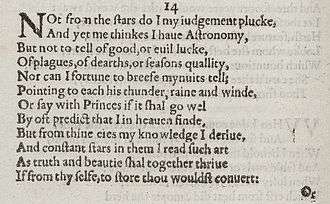

The first twelve lines of Sonnet 14 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Structure

Sonnet 14 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet, which consists of three quatrains followed by a couplet. It follows the traditional rhyme scheme of the form: ABAB CDCD EFEF GG. Like many of the others in the sequence, it is written in a type of metre called iambic pentameter, which is based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions per line.

Typically English sonnets present a problem or argument in the quatrains, and a resolution in the final couplet.[2] This sonnet suggests this pattern, but its rhetorical structure is more closely modeled upon the older Petrarchan sonnet which arranges the octave (the first eight lines) in contrast to the sestet (the final six lines).

Line 3 exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / But not to tell of good, or evil luck, (14.3)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

Historical Context

Some critics argue that the Fair Youth sequence follows a story-line told by Shakespeare.[3] Evidence that corroborates this is that the sonnets show a constant change of attitude that would seem to follow a day-by-day private journal entry.[3] Furthermore, there is an argument that the Fair Youth sequence was written to Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton.[4] Critics believe that Shakespeare would like him to marry and have an heir so that his beauty would live forever.[5] The historical timeline of the procreation sonnets directly relates to William Cecil Lord Burghley and the pressure he put on Southampton to marry his granddaughter Lady Elizabeth Vere (daughter of Edward de Vere).[5] To this day the relationship between Henry Wriothesly and Shakespeare is debated due to the fact that some believe it was romantic in nature, and not platonic.[6] Regardless most critics agree that Shakespeare wrote this sonnet in order to convince him to produce an heir.[5]

Exegesis

Sonnet 14 contains a speaker that may not know how to predict the future or what will happen, but they do know the value of procreating to retain one's beauty throughout the ages.

Quatrain 1

Quatrain 1 has multiple references to astronomy, and other literature. Edward Dowden argues that Philip Sidney's Astrophel and Stella is an influence in this sonnet due to the nature of both of the sonnets.[7] For example, Sonnet 26 of Sidney's Astrophel and Stella has a line "though duskie wits doe scorne Astrology.. who oft bewares my after following case, by only those two starres in Stella's face."[8] A. L. Rowse points out in both of these poems the speaker is unable to predict the future by using astrology, and can only predict the future through the object of their poem's eyes.[9]

According to Frederick Fleays, lines 3-4 are possible references to plagues that occurred in 1592–1593, and the dearths that followed in 1594–1596.[10] Alfread Rollins also states there was an irregularity in the seasons in 1595–1596, which all could have influenced these lines from Shakespeare.[11]

Quatrain 2

Lines 8–9 have influences from Ovid's Amores and Shakespeare's own "Love Labor's Lost". George Steevens points out that Shakespeare's early comedy included a line stating "From women's eyes this doctrine I derive."[12] In the context of Sonnet 14 it is explaining the importance of procreation, and that it is necessary.[11] Ovid's Amores has a similar line "at mihe te comitem auroras usque futuram- per me perque oculos, siders rostra, tuos."[13] Both Samuel Johnson and George Steevens noted the similar meaning and that it indicates Roman influence on Shakespeare's poetry.[12]

Quatrain 3

Lines 10-11 are saying that one can see that truth and beauty would thrive together; if only you would focus on the business of making provisions for yourself.[14]

Couplet

Shakespeare uses the portentous polysyllabic verb prognosticate with the alliteration 'doom and date' which is the stock in the trade of astrologers.[15] This is Shakespeare's prognostication, and it is delivered with a smile. West believed this due to the emphasis against the metre on 'this'.[15] Line 14 is saying that when one is dead, their truths and beauties come to an end as well.[14]

Interpretations

- Marianne Faithfull, for the 1999 compilation album, Emmaüs Mouvement (Virgin France)

- Ioan Gruffudd, for the 2002 compilation album, When Love Speaks (EMI)

References

- Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- "Basic Sonnet Forms". www.sonnets.org. Retrieved 2015-10-07.

- Crosman, Robert (1990). "Making Love out of Nothing at All: The Issue of Story in Shakespeare's Procreation Sonnets". Shakespeare Quarterly. doi:10.2307/2870777.

- Akrigg, G. P. V. (1968). Shakespeare and the Earl of Southampton. England: London: H. Hamilton. ISBN 0-241-01506-5.

- Boyle, W (1999). "Shakespeare, Southampton and the Sonnets: conference presentations explore competing theories". Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter.

- Thomson, Walter (1938). The sonnets of William Shakespeare & Henry Wriothesley, third earl of Southampton, together with a lover's complaint and the phoenix and turtle. England: Oxford : Printed and sold for the editor by B. Blackwell, and H. Young & sons, ltd., Liverpool.

- Dowden, Edward (1881). Shakespeare: A Critical Study of his Mind and Art. New York: Harper and Brothers.

- Marquis, T (January 1, 1896). "Sidney's 'Astrophel and Stella'". Poet Lore.

- Rowse, A. L. (1973). Shakespeare's sonnets- the problems solved: a modern edition with prose versions, introduction and notes. New York: Harper and Row.

- Fleay, Frederick (1892). A biographical chronicle of the English drama. England: B. Franklin.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward (1951). Sonnets. New York: Appleton Century Crofts.

- Shakespeare, William (1780). Supplement to the edition of Shakspeare's plays published in 1778 by Samuel Johnson and George Steevens. In two volumes. Containing additional observations ... to which are subjoined the genuine poems of the same author, and seven plays that have been ascribed to him; with notes by the editor and others. England: London.

- Turpin, William (May 2014). "Ovid's new muse: Amores 1.1". Classical Quarterly. doi:10.1017/S0009838813000876.

- Paterson, Don (2012). Reading Shakespeare's Sonnets. Essex, United Kingdom: Faber & Faber. pp. 45–46. ISBN 0-571-26399-2.

- West, David (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With a New Commentary by David West. London, England: Duckworth Overlook. pp. 53–54. ISBN 1-58567-921-6.

Further reading

- Baldwin, T. W. (1950). On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

- Hubler, Edwin (1952). The Sense of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- Schoenfeldt, Michael (2007). The Sonnets: The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare's Poetry. Patrick Cheney, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

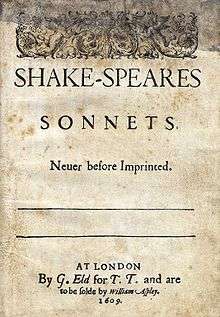

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

External links

.png)