Sonnet 101

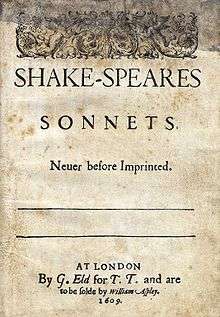

Sonnet 101 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a member of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man. The three other internal sequences include the procreation sonnets (1–17), the Rival Poet sequence (78–86) and the Dark Lady sequence (127–154). While the exact date of composition of Sonnet 101 is unknown, scholars generally agree that the group of Sonnets 61–103 was written mainly in the first half of the 1590s and was not revised before being published with the complete sequence of sonnets in the 1609 Quarto.[2]

| Sonnet 101 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The first line of Sonnet 101 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Synopsis

The Muse is chided for her absence and neglect of praise for the youth. The poet-speaker goes further, imagining the Muse responding that truth and beauty need no additions or explanations. The Muse is implored by the poet to praise the youth. The poet will teach her how to immortalize the youth's beauty.

Structure

Sonnet 101 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet has three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the typical rhyme scheme of the form ABAB CDCD EFEF GG and is composed in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The 11th line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / To make him much outlive a gilded tomb (101.11)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

The 7th line has a common metrical variation, an initial reversal:

/ × × / × / × / × / Beauty no pencil, beauty's truth to lay; (101.7)

Initial reversals are potentially present in lines 6 and 12, and a mid-line reversal ("what shall") is potentially present in line 1. The parallelism of "seem" and "shows" in the final line suggest a rightward movement of the fourth ictus (resulting in a four-position figure, × × / /, sometimes referred to as a minor ionic):

× / × / × / × × / / To make him seem, long hence, as he shows now. (101.14)

While Petrarchan sonnets by tradition have a volta at the end of line eight, in Shakespeare's sonnets this can occur as late as line 12 and sometimes not at all.[3] In Sonnet 101, a volta seems to occur at the end of line eight, as the poet-speaker, in a role-reversal with the Muse, begins to actively lead the Muse towards the couplet and there provides the Muse with a solution to the problem of "what to say and how to say it" thus ensuring that memory of youth will endure.[4]

Context

Within the sonnet sequence

In addition to Sonnet 100, Sonnet 101 is recognized as one of the only two sonnets in the complete sequence which directly invokes the Muse. These two sonnets in turn are part of the group of four sonnets, 100–103, wherein the poet-speaker deflects blame for his silence from himself onto the Muse, making excuses for having not written or if writing, not writing adequately.[5] Dubrow notes the use here of occupatio, that rhetorical method of announcing a topic which one will not discuss and by that announcement already commencing a discussion of it.[6] On the other hand, Stirling has noted the differences of 100–101 from 102–103 and from the larger group 97–104, and that by removing them, one creates a more cohesive sequence (97–99, 102–104) tied together by "the theme of absence and 'return'".[7] A new position for 100–101 is suggested as the introduction to a sequence (100–101, 63–68, 19, 21, 105) which develops with its "twin ideas of Time the destroyer—Verse the preserver."[8]

As mentioned above, the large group 61–103 was probably written mainly in the first half of the 1590s, and presented unrevised in 1609.[9] Together with two other groups, 1–60 ("... written mainly in the first half of the 1590s; revised or added to after 1600, perhaps as late as 1608 or 1609"[10]) and 104-26 ("... written around or shortly after 1600"[11]) they make up the largest subsection known as the Fair Youth Sonnets (1-126).[12]

The other three internal sequences of note are the Procreation sequence (1-17), the Rival Poet sequence (78-86) and the Dark Lady sequence (127-154).

Within Elizabethan literary society

The two most likely candidates for the Fair Youth are Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton, an early patron of Shakespeare, and William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke, a later patron. Duncan-Jones argues that Pembroke is the more likely candidate.[13] She also suggests that John Davies of Hereford, Samuel Daniel, George Chapman, and Ben Jonson are all plausible candidates for the role of Rival Poet in Sonnets 78–86.[14]

Atkins argues that pursuing a biographical context to the poems in Shakespeare's sequence is nonsensical and that a more productive focus of attention might be on the literary society of the time—which may have included small literary associations or academies, and for one of these, the sonnets perhaps were composed. The popular themes would have included the Renaissance philosophy of platonic ideas of Truth and Beauty and Love and the relationship of each to the others.[15]

Within Elizabethan national culture and society

In Shakespeare's time, the word 'pencil,' means paintbrush, though it can also mean style, or level of skill in painting, or "an agent or medium which brushes, delineates, or colors."(OED 1) Dundas describes the fascination of the English Renaissance poets with painting. Sonnet 24 uses the painter and painting as the extended conceit, pointing out the limits of the painter to capture the accurate image of beauty, and even then that the visual image may show no knowledge of the inward beauty of the heart. Sonnet 101 builds on that philosophy, that neither the painter nor the poet can ever accurately reflect the truth of the loved one's beauty so why not remain silent.[16] Martz extends the discussion by suggesting that the work of Sidney and Shakespeare is analogous to the transition from High Renaissance to Mannerist styles in that they may refer to the ideals of harmonious composition, but focus on the tensions, instabilities and anxieties and (in Shakespeare) darker moods in the images of the subjects depicted in their art.[17]

If, however "dyed" (defined as to tinge with color, (OED 1) as of textiles and clothing) as the key metaphor, then the concepts, values and motivations behind the English sumptuary laws become of plausible relevance. Indeed, a more direct reference to the dyer's profession is given in Sonnet 111, "And almost thence my nature is subdued / to what it works in, like the dyer's hand[.]" Here in Sonnet 101 as in others in the sequence Shakespeare can be seen as making reference to the "anxiety about the emulation of betters" that drove the regulation of apparel and its coloring.[18]

Exegesis

Quatrain 1

In the preceding Sonnet 100, the poet literally asks, "Where art thou, Muse, that thou forget'st so long / to speak of that which gives thee all thy might?" (Sonnet 100, 1-2), and then implores, "Return, forgetful Muse, and straight redeem" (Sonnet 100, 5) itself/the poet, by inspiring him his pen with "both skill and argument," (Sonnet 100, 8). By Sonnet 101, however, the poet has taken a very different tone with the Muse, and no longer simply begs or implores for inspiration, but rather asks "Oh truant Muse what shall be thy amends / for thy neglect of truth in beauty dyed?" (Sonnet 101,1-2). The poet has gone from speaking as passively inspired to demanding amends from the Muse for its neglect of he and his Fair Youth. The poet then implicates the Muse in his own plight, by declaring, "Both truth and beauty on my love depends; / so dost thou too, and therein dignified" (101, 3-4), meaning that both the poet and the Muse are given purpose by their function in praising truth and beauty.[19]

Quatrain 2

As mentioned above, rather than asking for inspiration, the poet demands explanation, though now he presumes his Muse's excuse for the neglect, which the poet takes to be that truth of beauty is self-evident, and needs no further embellishment. It is in the second and third line of this quatrain, or the sixth and seventh lines in the sonnet, where the rhythmic structure of Sonnet 101 becomes noteworthy. Whereas the rest of Sonnet 101 follows conventional structural patterns, it is in line 6 and 7, "Truth needs no colour with his colour fixed; / Beauty no pencil, beauty's truth to lay," that the rhythm deviates from the established norm, which is discussed in depth earlier in this article. Though there is no definitive explanation for this alteration, its inconsistency warrants speculation. If we assume that the difference in pattern is not an oversight on the part of Shakespeare, then it is conceivable that this creative idiosyncrasy was made for aesthetic or symbolic reasons. It is then pertinent to question why these particular lines are given this unique structural treatment. Putting aside aesthetic interpretation, it could be conceived that Shakespeare intentionally chose these two lines with which to assert freedom from the regular metrics of iambic pentameter, to show that truth and beauty should be singled out. Given this interpretation of the second and third lines of the quatrain, the fourth line, "But best is best, if never intermixed?" can even be read as the poet-speaker's assessment that his Muse does not see fit to embellish truth and beauty through poetic inspiration.

Quatrain 3

The poet rejects this neglect of praise that he has attributed to his Muse's will, and rationalizes that it is this very praise which will immortalize the Fair Youth, "to make him much outlive a gilded tomb / and to be praised of ages yet to be" (Sonnet 101, 11-12). The contextual use of the phrase "gilded tomb" potentially refers to two different concepts, one being the meaningless decadence of expensive burial chambers, and the other being a tome as in a large volume of literature. As T. Walker Herbert notes, "tomb and tome could be spelled tombe in the seventeenth century." "Granted that the external evidence is permissive rather than conclusive, let it be supposed to Shakespeare's ear that tome and tomb were sounded enough alike for purposes of a pun." (Herbert, 236, 239) A third concept is suggested by William Empson (p. 138) interpreting "tombe" so that "tomb is formal praise as would be written on a tombstone, whereas real merits of a man are closely connected with his faults." In other words, the poet-speaker is telling the muse he has the power to save his reputation when his social enemies might be writing the elegy or epitaph for his popularity, or possibly that the inner truth which is the source of his outward beauty will outlive the end of that youthful idea of beauty, or even that by the Muse singing his praise, the youth might be encouraged to sustain his lineage, even though he himself may grow old and pass on. Empson suggests that multiple ambiguous readings like this "must all combine to give the line its beauty and there is a sort of ambiguity in not knowing which of them to hold most clearly in mind. Clearly this is involved in all such richness and heightening of effect, and the machinations of ambiguity are among the very roots of poetry."[20][21]

Couplet

The poet ultimately declares to the Muses that he himself will show the Muse how to immortalize the Fair Youth. This is a significant change in attitude from the poet's previous prayers for inspiration in Sonnet 100, and even the poet's indignation at the beginning of Sonnet 101. The poet has gone from being passively inspired to a self-appointed leader of his own inspiration, which is a show of confidence that the poet does not necessarily maintain throughout the full body of sonnets.

References

- Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- Shakespeare, William (2012). Shakespeare's Sonnets : An Original-Spelling Text. Oxford;New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-19-964207-6.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine (2010). Shakespeare's Sonnets (Revised ed.). London: Arden Shakespeare. p. 96. ISBN 1-4080-1797-0.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine (2010). Shakespeare's Sonnets (Revised ed.). London: Arden Shakespeare. p. 97. ISBN 1-4080-1797-0.

- Butler, Samuel (1927). Shakespeare's Sonnets Reconsidered ([New ed.] ed.). London: J. Cape.

- Dubrow, Heather (1987). Captive Victors : Shakespeare's Narrative Poems and Sonnets. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Stirling, Brents (1960). "A Shakespeare Sonnet Group". PMLA (75.4): 346.

- Stirling, Brents (1960). "A Shakespeare Sonnet Group". PMLA (75.4): 344.

- Shakespeare, William (2012). Hammond, Paul (ed.). Shakespeare's Sonnets : An Original-Spelling Text. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 8.

- Shakespeare, William (2012). Hammond, Paul (ed.). Shakespeare's Sonnets : An Original-Spelling Text. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 8.

- Shakespeare, William (2012). Hammond, Paul (ed.). Shakespeare's Sonnets : An Original-Spelling Text. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 9.

- Shakespeare, William (2012). Hammond, Paul (ed.). Shakespeare's Sonnets : An Original-Spelling Text. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine (2010). Shakespeare's Sonnets (Revised ed.). London: Arden Shakespeare. pp. 52–69. ISBN 1-4080-1797-0.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine (2010). Shakespeare's Sonnets (Revised ed.). London: Arden Shakespeare. pp. 64–65. ISBN 1-4080-1797-0.

- Shakespeare, William (2007). Carl D. Atkins (ed.). Shakespeare's Sonnets : With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

- Dundas, Judith (1993). Pencils Rhetorique : Renaissance Poets and the Art of Painting. Newark Del. : London ; Cranbury, NJ: University of Delaware Press.

- Martz, Louis (December 1998). "Sidney and Shakespeare at Sonnets". Moreana. Angers, France: Association Amici Thomae Mori, France. 35 (135–136): 151–170. ISSN 0047-8105.

- Matz, Robert (2008). The World of Shakespeare's Sonnets : An Introduction. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co.

- Remarks on the Sonnets of Shakespeare. New York: James Miller. 1867.

- Herbert, T. Walter (1949). Shakespeare's Word Play on Tombe. The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 235–239. JSTOR 2909562.

- Empson, William (1966). Seven Types of Ambiguity. New York.

Further reading

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

.png)