Sonnet 63

Sonnet 63 is one of 154 sonnets published in 1609 by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is one of the Fair Youth sequence. Contrary to most of the other poems in the Fair Youth sequence, in sonnets 63 to 68 there is no explicit addressee, indeed the second person pronoun (you or thou) is not used anywhere in sonnets 63 to 68.

| Sonnet 63 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

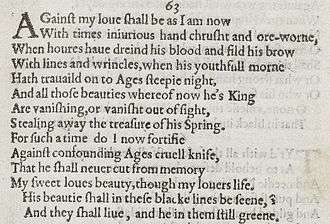

Sonnet 63 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Synopsis

In sonnet 63 the poet expresses his concern that the memory of his love's beauty be preserved and protected. The poet imagines a time when the young man will be old and worn, as he, the poet, is now. The passing of time will drain the young man's blood, carve wrinkles in his face, erode and wear away all of his beauty. Time will eventually take away the young man. To prevent the young man's beauty being cut from memory, this sonnet will be read and will preserve the memory of the young man's beauty.[2] Unlike Sonnet 2, in which immortality is gained through procreation, here it is gained in the reading of this poem ("these black lines").

Structure

Sonnet 63 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. The English sonnet has three quatrains, followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the typical rhyme scheme of the form, ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, and is composed in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The third line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / When hours have drained his blood, and filled his brow (63.3)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

The sonnet is quite metrically regular, but two variations stand out:

× / × / × / / × × / With time's injurious hand crushed and o'er-worn; (63.2) / × × / × / × / × / Stealing away the treasure of his spring; (63.8)

Reversals — such as the mid-line reversal "crush'd and", and the initial reversal "stealing" — can be used to bring special emphasis to words, especially verbs of action or motion, a practice Marina Tarlinskaja calls rhythmical italics.[3] Here, both instances highlight Time's cruel effects upon beauty.

Analysis

Like Sonnet 2, this poem makes use of cutting and crushing imagery to depict the effects of time in creating wrinkles on the face. The prevailing metaphors in this sonnet compare youthful beauty to riches, similar to Sonnet 4, and old age and death to night, similar to Sonnet 12.

The attention to the subject's mortality, returned to in this sonnet, remains the focus for the next two sonnets, and Sonnet 65 contains much the same resolution as this one does.

References

- Shakespeare, William. Duncan-Jones, Katherine. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Bloomsbury Arden 2010. p. 237 ISBN 9781408017975.

- Shakespeare, William. Duncan-Jones, Katherine. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Bloomsbury Arden 2010. p. 236 ISBN 9781408017975.

- Tarlinskaja, Marina (2014). Shakespeare and the Versification of English Drama, 1561–1642. Farnham: Ashgate. pp. 29–32. ISBN 978-1-4724-3028-1.

Further reading

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

.png)