Memorials to William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare has been commemorated in a number of different statues and memorials around the world, notably his funerary monument in Stratford-upon-Avon (c. 1623); a statue in Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey, London, designed by William Kent and executed by Peter Scheemakers (1740);[1] and a statue in New York's Central Park by John Quincy Adams Ward (1872).[2][3]

17th century

Shakespeare's funerary monument is the earliest memorial to the playwright, located inside Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, UK, the same church in which he was baptised. The exact date of its construction is not known, but must have been between Shakespeare's death in 1616 and 1623, when it is mentioned in the First Folio of the playwright's works.

The monument, by Gerard Johnson, is mounted on a wall above Shakespeare's grave. It features a bust of the poet, who holds a quill pen in one hand and a piece of paper in another. His arms are resting on a cushion. Above him is the Shakespeare family's coat of arms, on either side of which stands two allegorical figures: one, representing Labour, holds a spade, the other, representing Rest, holds a torch and a skull.

18th century

As Shakespeare's reputation rose, monuments began to be created in nationally significant locations. William Kent designed a statue for Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey. The design was executed by the sculptor Peter Scheemakers and installed in 1740. Its creation was funded by Lord Burlington and Alexander Pope, among others. At least two fundraising events were led by the efforts of the Shakespeare Ladies Club: a benefit performance of Julius Caesar on April 28, 1738 at Drury Lane and a benefit performance of Hamlet on April 10, 1739 at Covent Garden.[4][5] There are carved heads on the pedestal, which probably depict Queen Elizabeth I, Henry V and Richard III. Shakespeare is depicted leaning on books and pointing to a scroll which has a slightly misquoted version of Prospero's lines from The Tempest about the globe dissolving to "leave not a wrack behind". A variant of Kent's design was installed in a Glasgow theatre in 1764. It is now in the Theatre Royal in Dunlop Street.[6]

In 1757 the English actor David Garrick commissioned a marble statue of William Shakespeare from the French sculptor Louis-François Roubiliac for his Palladian Temple to Shakespeare at Hampton. Garrick himself is thought to have posed for the statue.[7] It was bequeathed, along with Garrick's books, to the British Museum in 1779; in 2005 it was transferred to the British Library.[8] Garrick later commissioned Roubiliac to produce a bust of the poet for his Shakespeare festival in Stratford in 1769;[9] this is now in the Garrick Club in London.[2]

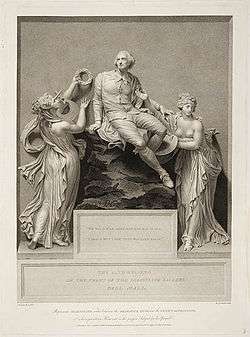

In 1788, in the exterior wall of John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery building, the architect George Dance the Younger placed Thomas Banks's sculpture Shakespeare attended by Painting and Poetry, for which the artist was paid 500 guineas. The sculpture depicted Shakespeare, reclining against a rock, between the Dramatic Muse and the Genius of Painting. Beneath it was a panelled pedestal inscribed with a quotation from Hamlet: "He was a Man, take him for all in all, I shall not look upon his like again".[10][11] The building was later used by the British Institution. After its demolition the monument was relocated to the garden of New Place in Stratford.

19th century

By the nineteenth century Shakespeare's reputation had advanced to the point of what came to be known as bardolatry. Statues and other memorials began to appear outside Britain, while in Britain itself Shakespeare's status as national poet was consolidated.

United States

New York City's Central Park contains a statue of Shakespeare that was commissioned in 1864 as a celebration of the tricentenary of Shakespeare's birth in 1564. Funds were raised by a performance of Julius Caesar in which Edwin Booth took the lead role, with John Wilkes Booth playing Mark Antony.[12] The statue was designed by John Quincy Adams Ward. Following the creation of the statue, in 1873 commissioners proposed that the Mall should be a designated location for sculpture and the statue was moved there, soon to be accompanied by others[13] (in 1986, a replica of the statue was made for the State Theater in Montgomery, Alabama, which has a yearly Shakespeare Festival).[14]

In 1888, a large seated statue by William Ordway Partridge was unveiled in Lincoln Park, Chicago and in 1896 a bronze statue of Shakespeare by Frederick William MacMonnies was erected as part of a series representing the world's geniuses in the gallery of the reading-room of the Library of Congress.

Britain

With the removal of Banks's sculpture to New Place in 1871 London boasted no outdoor public memorial to the bard, and the erection of the New York statue in 1872 made this omission particularly glaring. In 1874 the financier Baron Albert Grant, wishing to address this situation, installed a fountain with a marble statue of Shakespeare at its centre in the gardens of Leicester Square. Sculpted by Giovanni Fontana, this was a replica of Scheemakers's monument in Poets' Corner.[15] Another statue was erected in Stratford, London, a suburb with the same name as Shakespeare's home town.

In 1877 a committee was created in Stratford-upon-Avon to erect a memorial to Shakespeare. This originally comprised a theatre building, to be sited on land donated by the bank of the Avon within sight of the church where Shakespeare was buried. A statue was also created in 1888, the work of Lord Ronald Gower. This is situated in Stratford's Bancroft Gardens. The monument shows Shakespeare seated on a pedestal, surrounded, at ground level, by statues of Hamlet, Lady Macbeth, Prince Hal, and Falstaff. These characters were intended to be emblematic of Shakespeare's creative versatility: representing Philosophy, Tragedy, History, and Comedy.[13] Another statue is present in a niche on the exterior of the town hall building.

Other countries

Though most memorials are to be found in English speaking countries, there are also monuments elsewhere. In 1888 a statue was erected on the Boulevard Haussmann in Paris, designed by Paul Fournier.[16]

20th century

Britain

Between 1970 and 1993, an image of the Poets' Corner statue of Shakespeare appeared on the reverse of Series D £20 notes issued by the Bank of England. Alongside the statue was an engraving of the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet.[17][18]

A complex memorial to Shakespeare was created in Southwark Cathedral, which was his parish church when he lived in London close to the Globe Theatre. It is also the burial place of Shakespeare's brother Edmund, along with other Elizabethan actors and playwrights. A recumbent statue of Shakespeare, created by Henry McCarthy in 1912, was placed in a niche on which was carved images of Elizabethan Southwark depicting the Globe, Winchester Palace and the tower of the church. An elaborate stained glass window was also created, depicting Shakespearean characters. The original window was destroyed by a bomb blast in World War II but was replaced in 1954. A birthday celebration of Shakespeare is held every year in April.[19]

Continental Europe

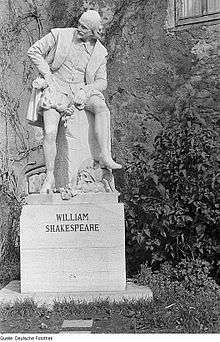

Despite Germany's early role in canonising Shakespeare it was not until 1904 that a statue was erected in Weimar showing him, as one critic has put it, "seated and staring into the distance with a bemused and thoughtful look".[20] It was designed by Otto Lessing.

In Denmark, a memorial statue was commissioned to commemorate the 300th anniversary of the publication of Hamlet in 1603.[21] The statue, designed by Louis Hasselriis, was funded by public subscription and erected in Elsinore, along with a sculpture of Hamlet.

Australia

A memorial in Sydney, Australia was erected in 1926, designed by Australian sculptor Sir Bertram MacKennal. It was commissioned by Henry Gullett (d. 4 August 1914), a former president of the Shakespeare Society of New South Wales. Paid for with a bequest from his estate, Gullett's daughter Lucy Gullett ensured that the commission was carried out after her father's death. It depicts not only Shakespeare at the top, but five of his most famous characters around the base – Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet embracing, Portia and Falstaff. It is located in Shakespeare Place, between the Mitchell Library (part of the State Library of New South Wales) and the Royal Botanic Gardens. In 1959 the statue was repositioned to make way for the Cahill Expressway.

Though initiated in 1889, the project to create a Shakespeare statue in Ballarat was not completed until 1960. Financial problems led to repeated shelving of the project. Eventually private donations to the fund produced sufficient resources to commission a bronze sculpture from Andor Meszaros, an Australian artist originally from Hungary. The statue depicts Shakespeare bowing, as if at the end of a performance.

North America

A statue was created for Logan Circle, Philadelphia in 1926, designed by Alexander Stirling Calder. It does not depict Shakespeare himself, but rather the figures of Touchstone the jester from As You Like It, representing comedy, and Hamlet, representing tragedy. Touchstone is lounging with his head tilted laughing, his feet hanging over the top of the tall stone pedestal and his left arm resting on Hamlet's legs. Hamlet is seated, brooding, his knife dangling over Touchstone's body.[22] The opening lines of the famous All the world's a stage speech from As You Like It are inscribed on the pedestal beneath the figures.

A statue made from tin was erected in the gardens outside the Festival Theatre, the principal theatre on the grounds of the Stratford Shakespeare Festival, held every year from April to November in Stratford, Ontario, Canada.

India

Theatre Road, a street in the central business district of Kolkata, India, was renamed Shakespeare Sarani on 24 April 1964, to mark the fourth birth centenary of William Shakespeare.[23]

Gallery

In 1864 a Shakespeare penny memorial poster stamp to commemorate the tercentenary of his birth was sold to raise funds for the Memorial Theatre at Stratford upon Avon.

In 1864 a Shakespeare penny memorial poster stamp to commemorate the tercentenary of his birth was sold to raise funds for the Memorial Theatre at Stratford upon Avon. A bust of Shakespeare in the St Mary Aldermanbury Garden, London (though depicting Shakespeare, this is actually a memorial to John Heminge and Henry Condell, editors of the First Folio).

A bust of Shakespeare in the St Mary Aldermanbury Garden, London (though depicting Shakespeare, this is actually a memorial to John Heminge and Henry Condell, editors of the First Folio). Copy of the Poets' Corner statue in Leicester Square, London

Copy of the Poets' Corner statue in Leicester Square, London Shakespeare statue in Stratford, Ontario.

Shakespeare statue in Stratford, Ontario. Shakespeare memorial, Logan Circle, Philadelphia, PA. Designed by Alexander Stirling Calder, 1923–26.

Shakespeare memorial, Logan Circle, Philadelphia, PA. Designed by Alexander Stirling Calder, 1923–26. William Parker Ordway's statue in Chicago.

William Parker Ordway's statue in Chicago.- Ordway's statue from another angle.

- Memorial in Southwark Cathedral, London

- This bust is placed on the city gate of Verona, with lines from Romeo and Juliet stating "there is no world without Verona walls..."

Bust of Shakespeare on the National Theatre building, Hviezdoslav Square, Bratislava.

Bust of Shakespeare on the National Theatre building, Hviezdoslav Square, Bratislava. Stained glass at Ottawa Public Library features Charles Dickens, Archibald Lampman, Duncan Campbell Scott, Lord Byron, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, William Shakespeare, Thomas Moore

Stained glass at Ottawa Public Library features Charles Dickens, Archibald Lampman, Duncan Campbell Scott, Lord Byron, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, William Shakespeare, Thomas Moore Coade stone statue of Shakespeare at Bonaly Tower, Edinburgh

Coade stone statue of Shakespeare at Bonaly Tower, Edinburgh

See also

- Shakespeare's reputation

- Portraits of Shakespeare

Notes

- "William Shakespeare". Westminster Abbey. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- "Memorials and Statues of William Shakespeare". Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- "William Shakespeare statue". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. 12 February 2007. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- Avery, Emmett L. (1956). "The Shakespeare Ladies Club". Shakespeare Quarterly 7 (2): p. 157

- Dobson, Michael (1992), The Making of the National Poet: Shakespeare, Adaptation and Authorship, 1660-1769, Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, pp. 137–38, 159–60 ISBN 0198183232.

- Raymond McKenzie, Gary Nisbet, Public Sculpture of Glasgow, Liverpool University Press, 2001, p. 434

- "Marble full-length figure of William Shakespeare by Louis-François Roubiliac". British Museum. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- Howes, Jennifer (11 November 2013). "The Shakespeare sculpture at the British Library". English and Drama blog. British Library. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- Michael Dobson The Making of the National Poet: Shakespeare, Adaptation and Authorship, 1660–1769, Oxford University Press, p. 6

- Sheppard, 325–38.

- William Shakespeare, Hamlet. Act I, scene ii. Wikisource. Retrieved on 15 January 2008.

- Villanova Magazine Archive – Winter 2001. Archived 29 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine It is sometimes mistakenly said that John Wilkes Booth played Cassius, cf. Frederick Wagner, American Actors and Actresses, Dodd Mead Company, New York, 1961.

- "Shakespeare Memorials". William-shakespeare.info. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- "William Shakespeare Statue, New York City department of Parks and Recreation". Nycgovparks.org. 12 February 2007. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- Ward-Jackson, Philip (2011). Public Sculpture of Historic Westminster: Volume 1. Liverpool University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link), pp. 114–15

- "Statue of Shakespeare (1564–1616) on Boulevard Haussmann, unveiled in 1888". Scholarsresource.com. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- "What Did Shakespeare Look Like?". The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- "Withdrawn Banknotes Reference Guide". Bank of England. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- "Southwark Cathedral – Shakespeare Memorial". Southwark.anglican.org. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- Stephen Kinzer, "Shakespeare, Icon in Germany" New York Times, 30 December 1995

- "American Dramatic Pilgrimage to the Tomb of Hamlet", New York Times, 20 January 1907.

- Patricia Vance, Intimate bicycle tours of Philadelphia: ten excursions to the city's art, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004, P.64.

- "Shakespeare Sarani". Kolkata Wheels.

.png)