Sonnet 42

Sonnet 42 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a part of the Fair Youth section of the sonnets addressed to an unnamed young man.

| Sonnet 42 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

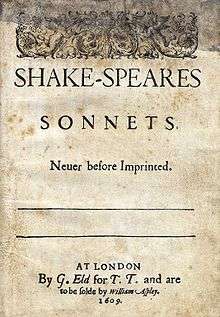

Sonnet 42 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Paraphrase

It is not my main ground of complaint that you have her, even though I loved her dearly; that she has you is my chief regret, a loss that touches me more closely. Loving offenders, I excuse you both thus: you love her, because you know I love her; similarly, she abuses me for my sake, in allowing my friend to have her. If I lose you, my loss is a gain to my love; and losing her, my friend picks up that loss. Both find each other, I lose both, and both lay this cross on me for my sake. But there is one consolation in this thought: my friend and I are one; therefore she loves me alone.[2]

Structure

Sonnet 42 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet. This type of sonnet consists of three quatrains followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the form's typical rhyme scheme, ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, and is written in a type of poetic metre called iambic pentameter based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. Line 10 exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / And losing her, my friend hath found that loss; (42.10)

The first three lines may be scanned:

× / × / × × / / × / That thou hast her it is not all my grief, × / × / × / × / × / (×) And yet it may be said I loved her dearly; × / × / × / × / × / That she hath thee is of my wailing chief, (42.1-3)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus. (×) = extrametrical syllable.

In the first and third lines, Shakespeare emphasizes pronouns by putting them in metrically strong positions, encouraging the reader to place contrastive accent on them, thereby emphasizing the antithetical relationships plaguing the Speaker. This technique is common in the Sonnets, and continues through this sonnet. The second line has a final extrametrical syllable or feminine ending (one of six in this sonnet).

Analyses and criticism

Some of the sonnets discuss a love triangle between the speaker, his mistress and a young man. In sonnet 42, this young man is presented as the speaker's 'friend'. The primary objective of this sonnet is to define the speaker's role in the complex relationship between the youth and the mistress.

Sonnet 42 is the final set of three sonnets known as the betrayal sonnets (40, 41, 42) that address the fair youth's transgression against the poet: stealing his mistress.[3] This offense was referred to in Sonnets 33–35, most obviously in Sonnet 35, in which the fair youth is called a "sweet thief." This same imagery is used again in Sonnet 40, when the speaker says, "I do forgive thy robbery, gentle thief." Sonnet 41 implies that it is easy for the speaker to forgive the fair youth his betrayal, since it is the mistress that "woos," tempted by the fair youth's beauty just as the speaker admires it. This affair is discussed later in sonnet 144-a poem which further suggests that the young man and the dark lady are lovers; "…my female evil tempteth my better angel from my side".[4]

In Helen Vendler's The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets, it is noted -- "By inserting himself somehow as cause or agent of the relation between the young man and the mistress, the speaker preserves a connection with the young man which is the overriding motive of this poem".[5] The idea that the fair youth and the poet are "one" is common in the sonnets; for example, it was also asserted in Sonnets 36, 39, and 40. A closer look at Sonnet 36 illustrates this point further, "In our two loves there is but one respect".[6] A possible reason the speaker emphasizes the oneness between himself and the youth is to align himself with the youth as opposed to his mistress.

Sonnet 42 uses feminine rhymes at the end of the lines: especially in the second quatrain as a poetic device, similar to sonnet 40.[7] "The poem is essentially a sad one…it's sadness heightened by the feminine endings, six in all [out of seven]".[8] Many critics seem to agree with this reading of the feminine endings, and note that additionally, the author uses two words to imply the emotionality tied up in his sonnet. The word "loss" is repeated throughout this poem, appearing six times. The repetition of this word emphasizes how strongly the speaker feels that he has been deprived of the two most important relationships in his life: the fair youth and the mistress. The word "loss" is balanced by the word "love," which also appears six times. They appear together in line 4, "A loss in love that touches me more nearly," referring to the poet's loss of the fair youth to his former mistress. Again in line 9, the two words are woven into the same line, "If I lose thee, my loss is my love's gain." These perfectly balanced words emphasize the main point of the sonnet as being about loss of love.[9]

The use of the term "loving offenders" in line 5 can have two meanings: that the offenders (the fair youth and the mistress) are in love; but it can also mean that they seem to enjoy their offense. This line, along with line 12, "And both for my sake lay on me this cross," hearken back to Sonnet 34, in which the speaker declares, "The offender's sorrow lends but weak relief / To him that bears the strong offence's cross." The biblical allusion of the cross ties the poet himself to Jesus in his suffering so that others might be happy, relieved of their sins.[10] Hammond writes that he feels the author was projecting himself as a martyr, a Christ like figure bearing the cross. Hammond reads line 5, "loving offenders" to mean equally as a vocative or self description; saying, 'it is my nature to love those who offend against me'. It appears that most critics agree that the author himself is accepting the 'cross' in this poem.[11]

The exaltation "Sweet flattery!" at the end of the sonnet indicates sarcasm, since "flattery" usually indicates dishonest beauty. The speaker makes the argument that since he and the youth are one, they must then share the same woman. Because the mistress and the youth are having an affair, the speaker comes to the logical conclusion that he and the youth are that much closer. Atkins illustrates this, "…we are meant to understand…that the flattery exists nowhere outside the poet's imagination".[12]

Notes

- Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- (Hammond 59)

- (Vendler 217)

- (Greenblatt 1803)

- (Vendler, p. 220)

- (Greenblatt pg. 1766)

- (Hammond, 59)

- (Atkins 124)

- (Atkins, 124)

- (Hammond 58)

- (Rowse, 87)

- (Atkins 124)

References

- Rowse, A.L. Shakespeare's Sonnets, the Problems Solved. pp. 86–87 2nd Ed. Harper Row Publishers. New York, New York. 1965.

- Hammond, Gerald. The Reader and Shakespeare's Young Man Sonnets. Pgs 58–69. Barnes and Noble Books. New Jersey 1981.

- Shakespeare, William. Sonnet 42. The Norton Shakespeare. Edited by Stephen Greenblatt. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1997.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

.png)