Dark Lady (Shakespeare)

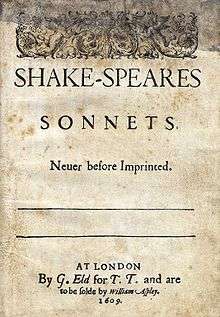

The Dark Lady is a woman described in Shakespeare's sonnets (sonnets 127–154) and so called because the poems make it clear that she has black wiry hair and dark, brown, "dun" coloured skin. The description of the Dark Lady distinguishes itself from the Fair Youth sequence by being overtly sexual. Among these, Sonnet 151 has been characterised as "bawdy" and is used to illustrate the difference between the spiritual love for the Fair Youth and the sexual love for the Dark Lady.[1] The distinction is commonly made in the introduction to modern editions of the sonnets.[1] As with the Fair Youth sequence, there have been many attempts to identify her with a real historical individual. A widely held scholarly opinion, however, is that the "dark lady" is nothing more than a construct of Shakespeare's imagination and art, and any attempt to identify her with a real person is "pointless".[2]

Speculation about the Dark Lady

The question of the true identity of the Dark Lady is an unsolved, controversial issue because of the insufficiency of historical detail. Some believe that she might be of Mediterranean descent with dark hair and dark eyes of Greece, Spain, Italy and Southern France. Other scholars have suggested, given Shakespeare's description of her dark, dun-colored skin and black wiry hair, that the Dark Lady might have been a woman of African descent. Ultimately, "none of the many attempts at identifying the dark lady…are finally convincing".[3]

Emilia Lanier

In 1973 A. L. Rowse claimed to have solved the identity of the Dark Lady in his book Shakespeare's Sonnets—the Problem Solved, based upon his study of astrologer Simon Forman's journal entries describing his meetings with Emilia Lanier.[4][5] It was later shown that Rowse had based his identification on a misreading of Forman's text: Forman had described Lanier as "brave in youth", not "brown in youth", but Rowse, while later correcting his misreading, continued to defend his argument.[6][7] In the diaries, Emilia is described as the mistress of Lord Hunsdon, the Queen's Lord Chamberlain. She seemed to have similar qualities to ones of the Dark Lady. For example, Emilia was so attractive to men that during the years of being Hunsdon's mistress, she may have been viewed as a prostitute. She might have been a musician because she was a member of the Bassano family which was famous for providing the music to entertain the Courts of Elizabeth I and James I. They were Italians and Emilia may have been of Mediterranean descent.[2]

However there are academics, such as David Bevington of the University of Chicago, who refuse to acknowledge the theory that Lanier was the Dark Lady not only due to the lack of any direct proof but also because the claimed association with Shakespeare tends to overshadow her own literary achievements: she published her celebrated collection of poems Salve Deus Rex Judæorum in 1611.[8][9]

Black Luce

G. B. Harrison, writing in 1933, notes that a Clerkenwell brothel-owner known as "Black Luce" had participated in the 1601–1602 Christmas revels at Gray's Inn (under the Latinized stage-name "Lucy Negro") and that she could there have encountered Shakespeare, as this was the occasion of the first performance of Twelfth Night. Harrison "tentatively" proposes Black Luce as the Dark Lady.[10] Two Clerkenwell brothel-keepers carried the nickname of "Black Luce"—Lucy Baynham and Lucy Morgan—but there is no evidence that either was of African descent.[11] Duncan Salkeld, a Shakespearean scholar from the University of Chichester, while acknowledging that "[t]he records do not link her directly with Shakespeare", established that Luce had multiple connections to London's theatrical scene.[12]

Wife of John Florio

Jonathan Bate in his The Genius of Shakespeare (2008) considers the case for both Lanier and Luce, before suggesting his own "pleasing fancy" that the unnamed, "low-born" but "witty and talented" wife of Italian linguist John Florio (and sister of poet Samuel Daniel[13][14]) was the Dark Lady, the lover of not only Shakespeare but also of Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton, who was at the time the patron of both the linguist and the playwright. Bate acknowledges the possibility that the sonnets may be no more than Shakespeare's "knowing imaginings", rather than allusions to actual events.[15]

Aubrey Burl, a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and commentator on prehistoric monuments, takes up the case that the Dark Lady is the wife of John Florio, whom he names as "Aline Florio". He arrives at his theory from a play-on-words he invented: the name of the dark-haired character Rosaline in Love's Labours Lost being suggested to Shakespeare by combining "rose" from the earl's family name of "Wriothesley" and "Aline" from a popular contemporary given name. Burl lists eight possible contenders for the Dark Lady's true identity, and finally asserts that Florio's wife is the real one, using some clues which were mentioned in Shakespeare's work: she was dark-haired, self-centred, and enjoyed sex. According to him, Mrs. Florio loved "for her own gratification", indulged in "temptation and callously self-satisfied betrayal of her husband", which coincides with features of the Dark Lady. He also suggests that the fact that she was born of low degree in Somerset explains the darkness of her complexion. Burl reasons that Florio probably first met Shakespeare at Titchfield, the Wriothesley family seat in Hampshire, and met him again in London at Florio's home.[16]

Saul Frampton of the University of Westminster identifies Samuel Daniel's birthplace as Wilton, near Marlborough, Wiltshire, citing William Slatyer's The history of Great Britain (1621), with the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography also recording a connection between the Daniel family and Marlborough. Frampton notes that the baptismal records of the parish contain an entry for one "Avisa Danyell" (dated 8 February 1556) and from this he deduces that this was Samuel's sister and therefore John Florio's wife. Thus, Avisa Florio was the Dark Lady.[17][18][19]

The speculations that Florio’s wife, of whatever baptismal name and relationship with Shakespeare, was Daniel's sister may be based on an original, incorrect interpretation. This was first made by Anthony à Wood (offering no authority) in his Athenæ Oxonienses of 1691. There is no documentary evidence to support this: rather, à Wood arrived at his conclusion from a passage of text where Daniel names Florio as his "brother" in introductory material to the latter’s famous translation of Michel de Montaigne’s Essays. If this were referring (in today’s terms) to his "brother-in-law" this could, therefore, have been the marriage of either man’s sister to the other. Furthermore, in the prevalent usage of the time (ignored by à Wood), this may simply signify that they were both members of the same "brotherhood": in this instance, both men were Grooms of the privy chamber (an honorary and not a functional office) and not related by marriage at all.[13][20][21]

Mary Fitton

Based upon the recurring theme in the early sonnets of two men vying for a lady's affection, often assumed to be Shakespeare and William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke, Herbert's mistress Mary Fitton has accordingly been proposed as the "Dark Lady". The first to make this suggestion was Thomas Tyler in the preface to his 1890 facsimile edition of the Sonnets but later commentators have assessed the depiction of the rivalry as a "fictitious situation" presented for poetic effect. When a portrait of Fitton, showing her to have fair complexion, brown hair and grey eyes, was discovered in 1897 the identification fell from favour. It was Fitton whom George Bernard Shaw had in mind when writing his play The Dark Lady of the Sonnets (below).[22][23][24]

Jacqueline Field

Field was the French-born wife of Shakespeare's friend and publisher Richard Field. The "not impeccable" reasoning provided by Charlotte Carmichael Stopes, a lecturer in literary history, to justify the claim does not form a strong case, comprising little more than: “as a Frenchwoman…she would have had dark eyes, a sallow complexion and that indefinable charm", so matching the character in the sonnets.[25][26]

Jennet Davenant

Originally arising from nothing more than the poet William Davenant's boast that he was the illegitimate son of Shakespeare, Jennet (or Jane) Davenant, the wife of a tavern-keeper on the route between London and Stratford, has been proposed as the Dark Lady.[27][28]

In popular culture

George Bernard Shaw's short play The Dark Lady of the Sonnets (1910) was written in support of a campaign for a national theatre in Britain; Shakespeare encounters Queen Elizabeth while attempting an assignation with the Dark Lady and commends the project to her.

In the Doctor Who series 3 episode "The Shakespeare Code", set in 1599, Shakespeare becomes infatuated with the Tenth Doctor's new companion Martha Jones, a Black British woman. At the end of the episode, after deducing that she is from the future, he calls her his "dark lady" and recites Sonnet 18 for her.

References

- Matz, Robert. The World of Shakespeare's Sonnets: An Introduction. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-7864-3219-6.

- Lasocki, David; Prior, Roger (1995). The Bassanos : Venetian musicians and instrument makers in England, 1531-1665. Abingdon, England: Routledge. pp. 114–6. ISBN 9780859679435.

- Holland, Peter (23 September 2004). "Shakespeare, William (1564–1616)". ODNB. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25200.

- Rowse, A. L. (1973). Shakespeare's sonnets - the problems solved. London: Macmillan. pp. xxxiv–xxxv. ISBN 9780333147344.

- Cook, Judith (2001). Dr Simon Forman : a most notorious physician. London: Chatto & Windus. p. 101. ISBN 978-0701168995.

- Rowse, A. L. (1974). The case books of Simon Forman : sex and society in Shakespeare's age. London: Cox & Wyman. p. 110. ISBN 9780330247849.

- Edwards, Philip; et al., eds. (2008). Shakespeare's styles : essays in honour of Kenneth Muir. Cambridge University Press. pp. 233–235. ISBN 978-0521616942.

- Bevington, David (2015). "Rowse's Dark Lady". In Grossman, Marshall (ed.). Aemilia Lanyer: Gender, Genre, and the Canon. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813149370.

- Woods, Susanne, ed. (1993). The Poems of Aemilia Lanyer: Salve Deus Rex Judæorum. Oxford University Press. p. xix.

Rowse's fantasy has tended to obscure Lanyer as a poet.

- Bagshawe, George (1933). Shakespeare under Elizabeth. New York: H Holt & Co. pp. 64, 310. OCLC 560738426.

- Kaufmann, Miranda (2017). "9". Black Tudors : the untold story. London: Oneworld. ISBN 9781786071842.

- Salkeld, Duncan (2012). "Shakespeares, the Clerkenwell Madam and Rose Flower". Shakespeare among the courtesans : prostitution, literature, and drama, 1500-1650. Farnham, England: Ashgate. ISBN 9780754663874.

- à Wood, Anthony (1691). Bliss, Philip (ed.). Athenæ Oxonienses (1815 ed.). p. 381.

[Florio] having married the sister of Samuel Daniel…

- O'Connor, Desmond (3 January 2008). "Florio, John (1553–1625". ODNB. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9758).

- Bate, Jonathan (2008). "The dark lady". The genius of Shakespeare. Oxford: Picador. p. 94. ISBN 9780330458436.

- Burl, Aubrey (15 June 2012). Shakespeare's mistress : the mystery of the dark lady revealed. Stroud, England: Amberley. ISBN 978-1445602172.

- Slatyer, William (1621). The History of Great Britanie from the first peopling of this island to this present raigne of o[u]r happy and peacefull Monarke K. James. London: William Stansby. OCLC 23246845.

- Frampton, Saul (10 August 2013). "In search of Shakespeare's dark lady". The Guardian.

- Pitcher, John (September 2004). "Daniel, Samuel (1562/3–1619)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- Corney, Bolton (1 July 1865). "Samuel Daniel and John Florio". Notes and Queries. Vol. 3/8. London.

- de Montaigne, Michel (1603). Essays. Translated by Florio, John.

To my deare brother and friend M. John Florio, one of the Gentlemen of hir Maiesties most Royall Privie Chamber

- Tyler, Thomas (1890). "Preface". Shakespeare's Sonnets. London: David Nutt. p. vi. OCLC 185191423.

- Lee, Sidney. "Fitton, Mary". Dictionary of National Biography.

- Edmondson, Paul; Wells, Stanley (eds.). Shakespeare's sonnets. Oxford University Press. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-0199256105.

- Schoenbaum, Samuel (1977). William Shakespeare : a compact documentary life. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-0198120469.

- Stopes, Charlotte Carmichael (1914). Shakespeare's Environment (1918 ed.). London: G. Bell and Sons. p. 155. OCLC 504848257.

- Aubrey, John (1696). Barber, Richard (ed.). Brief Lives (1982 ed.). Woodbridge, England: Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 90. ISBN 9780851152066.

- Wells, Stanley (8 April 2010). Shakespeare, Sex, & Love. Oxford University Press. p. 73. ISBN 9780199578597.