Sonnet 62

Sonnet 62 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It is a member of the Fair Youth sequence, addressed to the young man with whom Shakespeare shares an intimate but tormented connection. This sonnet brings together a number of themes that run through the cycle: the speaker's awareness of social and other differences between him and the beloved; the power and limitations of poetic art; and the puzzling sense in which love erases the boundaries between individuals.

| Sonnet 62 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

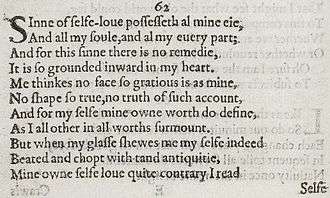

The first eleven lines of Sonnet 62 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Structure

Sonnet 62 is an English or Shakespearean sonnet, with three quatrains followed by a final rhyming couplet. It follows the form's typical rhyme scheme, ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, and is composed in a type of poetic metre known as iambic pentameter based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The sixth line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / No shape so true, no truth of such account, (62.6)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus.

The first line (as do some others) has an initial reversal:

/ × × / × / × / × / Sin of self-love possesseth all mine eye, (62.1)

Reversals can be used to bring special emphasis to words — especially action verbs, as in line ten's "beated" and line fourteen's "painting" — a practice Marina Tarlinskaja calls rhythmical italics.[2]

Source and analysis

The conceit of the poem is derived most nearly from Petrarch; however, the idea of lovers who have in some sense exchanged souls is commonplace and proverbial. The connected theme—the speaker's unworthiness compared to his beloved—is likewise traditional.

Line 7 has posed some problems. Edward Dowden hypothesized that "for myself" meant "for my own satisfaction," and certain editors suggest that "do" be amended to "so." Consensus, however, has settled on some version of the gloss of Nicolaus Delius: "I define my own worth for myself," with "do" as an intensifier.

For "beated" in line 10, Edmond Malone suggested "bated," and George Steevens "blasted." Dowden speculated, without accepting, the possibility that "beated" referred to a process of tanning; John Shakespeare was a glover. Stephen Booth notes that the use of "bating" in this sense is not attested before the nineteenth century.

Helen Vendler sees the speaker of the poem as harshly criticizing his own weakness and foolishness, but for most critics the poem is lighter in mood. Though it echoes other poems in the sequence which present the connections created by love as painful, in this poem, the presence of the beloved is comforting rather than terrifying.

Interpretations

- John Sessions, for the 2002 compilation album, When Love Speaks (EMI Classics)

Notes

- Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- Tarlinskaja, Marina (2014). Shakespeare and the Versification of English Drama, 1561–1642. Farnham: Ashgate. pp. 29–32. ISBN 978-1-4724-3028-1.

References

- Baldwin, T. W. On the Literary Genetics of Shakspeare's Sonnets. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1950.

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

.png)