Androgyny

Androgyny is the combination of masculine and feminine characteristics into an ambiguous form. Androgyny may be expressed with regard to biological sex, gender identity, gender expression, or sexual identity.

| Intersex topics |

|---|

|

|

Medicine and biology |

|

History and events |

| Part of a series on |

| Transgender topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Health care and medicine |

|

Rights issues

|

|

Society and culture

|

|

By country

|

|

|

When androgyny refers to mixed biological sex characteristics in humans, it often refers to intersex people. As a gender identity, androgynous individuals may refer to themselves as non-binary, genderqueer, or gender neutral. As a form of gender expression, androgyny can be achieved through personal grooming, fashion, or a certain amount of THT treatment. Androgynous gender expression has waxed and waned in popularity in different cultures and throughout history.

Etymology

Androgyny as a noun came into use c. 1850, nominalizing the adjective androgynous. The adjective use dates from the early 17th century and is itself derived from the older French (14th Century) and English (c. 1550) term androgyne. The terms are ultimately derived from Ancient Greek: ἀνδρόγυνος, from ἀνήρ, stem ἀνδρ- (anér, andro-, meaning man) and γυνή (gunē, gyné, meaning woman) through the Latin: androgynus,[1] The older word form androgyne is still in use as a noun with an overlapping set of meanings.

History

Androgyny among humans – expressed in terms of biological sex characteristics, gender identity, or gender expression – is attested to from earliest history and across world cultures. In ancient Sumer, androgynous and intersex men were heavily involved in the cult of Inanna.[2]:157–158 A set of priests known as gala worked in Inanna's temples, where they performed elegies and lamentations.[2]:285 Gala took female names, spoke in the eme-sal dialect, which was traditionally reserved for women, and appear to have engaged in sexual acts with men.[3] In later Mesopotamian cultures, kurgarrū and assinnu were servants of the goddess Ishtar (Inanna's East Semitic equivalent), who dressed in female clothing and performed war dances in Ishtar's temples.[3] Several Akkadian proverbs seem to suggest that they may have also engaged in sexual activity with men.[3] Gwendolyn Leick, an anthropologist known for her writings on Mesopotamia, has compared these individuals to the contemporary Indian hijra.[2]:158–163 In one Akkadian hymn, Ishtar is described as transforming men into women.[3]

The ancient Greek myth of Hermaphroditus and Salmacis, two divinities who fused into a single immortal – provided a frame of reference used in Western culture for centuries. Androgyny and homosexuality are seen in Plato's Symposium in a myth that, according to Plato, Aristophanes tells the audience, possibly with a comic intention.[4] People used to be spherical creatures, with two bodies attached back to back who cartwheeled around. There were three sexes: the male-male people who descended from the sun, the female-female people who descended from the earth, and the male-female people who came from the moon. This last pairing represented the androgynous couple. These sphere people tried to take over the gods and failed. Zeus then decided to cut them in half and had Apollo repair the resulting cut surfaces, leaving the navel as a reminder to not defy the gods again. If they did, he would cleave them in two again to hop around on one leg. This is one of the earlier written references to androgyny - and the only case in classical greek texts that female homosexuality (lesbianism) is ever mentioned. Other early references to androgyny include astronomy, where androgyn was a name given to planets that were sometimes warm and sometimes cold.[5]

Philosophers such as Philo of Alexandria, and early Christian leaders such as Origen and Gregory of Nyssa, continued to promote the idea of androgyny as humans' original and perfect state during late antiquity.”[6] In medieval Europe, the concept of androgyny played an important role in both Christian theological debate and Alchemical theory. Influential Theologians such as John of Damascus and John Scotus Eriugena continued to promote the pre-fall androgyny proposed by the early Church Fathers, while other clergy expounded and debated the proper view and treatment of contemporary hermaphrodites.[6]

Western esotericism’s embrace of androgyny continued into the modern period. A 1550 anthology of Alchemical thought, De Alchemia, included the influential Rosary of the Philosophers, which depicts the sacred marriage of the masculine principle (Sol) with the feminine principle (Luna) producing the "Divine Androgyne," a representation of Alchemical Hermetic beliefs in dualism, transformation, and the transcendental perfection of the union of opposites.[7] The symbolism and meaning of androgyny was a central preoccupation of the German mystic Jakob Böhme and the Swedish philosopher Emanuel Swedenborg. The philosophical concept of the “Universal Androgyne” (or “Universal Hermaphrodite”) – a perfect merging of the sexes that predated the current corrupted world and/or was the utopia of the next – also plays a central role in Rosicrucian doctrine[8][9] and in philosophical traditions such as Swedenborgianism and Theosophy. Twentieth century architect Claude Fayette Bragdon expressed the concept mathematically as a magic square, using it as building block in many of his most noted buildings.[10]

Symbols and iconography

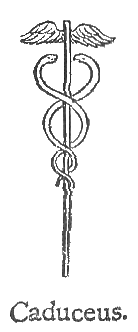

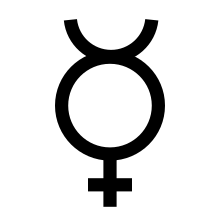

In the ancient and medieval worlds, androgynous people and/or hermaphrodites were represented in art by the caduceus, a wand of transformative power in ancient Greco-Roman mythology. The caduceus was created by Tiresias and represents his transformation into a woman by Juno in punishment for striking at mating snakes. The caduceus was later carried by Hermes/Mercury and was the basis for the astronomical symbol for the planet Mercury and the botanical sign for hermaphrodite. That sign is now sometimes used for transgender people.

Another common androgyny icon in the medieval and early modern period was the Rebis, a conjoined male and female figure, often with solar and lunar motifs. Still another symbol was what is today called sun cross, which united the cross (or saltire) symbol for male with the circle for female.[11] This sign is now the astronomical symbol for the planet Earth.[12]

Mercury symbol derived from the Caduceus |

A Rebis from 1617 |

"Rose and Cross" Androgyne symbol |

Alternate "rose and cross" version |

Biological

Historically, the word androgynous was applied to humans with a mixture of male and female sex characteristics, and was sometimes used synonymously with the term hermaphrodite.[13] In some disciplines, such as botany, androgynous and hermaphroditic are still used interchangeably.

When androgyny is used to refer to physical traits, it often refers to a person whose biological sex is difficult to discern at a glance because of their mixture of male and female characteristics. Because androgyny encompasses additional meanings related to gender identity and gender expression that are distinct from biological sex, today the word androgynous is rarely used to formally describe mixed biological sex characteristics in humans. [14] In modern English, the word intersex is used to more precisely describe individuals with mixed or ambiguous sex characteristics. However, both intersex and non-intersex people can exhibit a mixture of male and female sex traits such as hormone levels, type of internal and external genitalia, and the appearance of secondary sex characteristics.

Psychological

Though definitions of androgyny vary throughout the scientific community, it is generally supported that androgyny represents a blending of traits associated with both masculinity and femininity. In psychological study, various measures have been used to characterize gender, such as the Bem Sex Role Inventory, the Personal Attributes Questionnaire.[15]

Broadly speaking, masculine traits are categorized as agentic and instrumental, dealing with assertiveness and analytical skill. Feminine traits are categorized as communal and expressive, dealing with empathy and subjectivity.[16] Androgynous individuals exhibit behavior that extends beyond what is normally associated with their given sex.[17] Due to the possession of both masculine and feminine characteristics, androgynous individuals have access to a wider array of psychological competencies in regards to emotional regulation, communication styles, and situational adaptability. Androgynous individuals have also been associated with higher levels of creativity and mental health.[18][19]

Bem Sex-Role Inventory

The Bem Sex-Role Inventory (BSRI) was constructed by the early leading proponent of androgyny, Sandra Bem (1977).[20] The BSRI is one of the most widely used gender measures. Based on an individual's responses to the items in the BSRI, they are classified as having one of four gender role orientations: masculine, feminine, androgynous, or undifferentiated. Bem understood that both masculine and feminine characteristics could be expressed by anyone and it would determine those gender role orientations.[21]

An androgynous person is an individual who has a high degree of both feminine (expressive) and masculine (instrumental) traits. A feminine individual is ranked high on feminine (expressive) traits and ranked low on masculine (instrumental) traits. A masculine individual is ranked high on instrumental traits and ranked low on expressive traits. An undifferentiated person is low on both feminine and masculine traits.[20]

According to Sandra Bem, androgynous individuals are more flexible and more mentally healthy than either masculine or feminine individuals; undifferentiated individuals are less competent.[20] More recent research has debunked this idea, at least to some extent, and Bem herself has found weaknesses in her original pioneering work. Now she prefers to work with gender schema theory.

One study found that masculine and androgynous individuals had higher expectations for being able to control the outcomes of their academic efforts than feminine or undifferentiated individuals.[22]

Personal Attributes Questionnaire

The Personal Attributes Questionnaire (PAQ) was developed in the 70s by Janet Spence, Robert Helmreich, and Joy Stapp. This test asked subjects to complete a survey consisting of three sets of scales relating to masculinity, femininity, and masculinity-femininity. These scales had sets of adjectives commonly associated with males, females, and both. These descriptors were chosen based on typical characteristics as rated by a population of undergrad students. Similar to the BSRI, the PAQ labeled androgynous individuals as people who ranked highly in both the areas of masculinity and femininity. However, Spence and Helmreich considered androgyny to be a descriptor of high levels of masculinity and femininity as opposed to a category in and of itself.[15]

Gender identity

An individual's gender identity, a personal sense of one's own gender, may be described as androgynous if they feel that they have both masculine and feminine aspects. The word androgyne can refer to a person who does not fit neatly into one of the typical masculine or feminine gender roles of their society, or to a person whose gender is a mixture of male and female, not necessarily half-and-half. Many androgynous individuals identify as being mentally or emotionally both masculine and feminine. They may also identify as "gender-neutral", "genderqueer", or "non-binary". A person who is androgynous may engage freely in what is seen as masculine or feminine behaviors as well as tasks. They have a balanced identity that includes the virtues of both men and women and may disassociate the task with what gender they may be socially or physically assigned to.[23] People who are androgynous disregard what traits are culturally constructed specifically for males and females within a specific society, and rather focus on what behavior is most effective within the situational circumstance.[23]

Many non-western cultures recognize additional androgynous gender identities. Jewish culture recognizes the Tumtum and Androgynos genders. Chinese culture has the Yinyang ren gender. The Bugis of Indonesia recognize five genders, Bissu representing the androgynous category. In Hawaiian culture, the third gender Māhū is recognized. In Oaxacan Zapotec culture, the Muxe are recognized as a third gender. In India, the Hijra is the third androgynous gender. Samoans accept Fa’afafine as a third gender. Native American culture includes Two Spirit as a general third gender.

Gender expression

Gender expression, which includes a mixture of masculine and feminine characteristics, can be described as androgynous. The categories of masculine and feminine in gender expression are socially constructed, and rely on shared conceptions of clothing, behavior, communication style, and other aspects of presentation. In some cultures, androgynous gender expression has been celebrated, while in others, androgynous expression has been limited or suppressed. To say that a culture or relationship is androgynous is to say that it lacks rigid gender roles, or has blurred lines between gender roles.

The word genderqueer is often used by androgynous individuals to refer to themselves, but the terms genderqueer and androgynous are neither equivalent nor interchangeable.[24] Genderqueer is not specific to androgynes, and does not denote gender identity. It may refer to any person, cisgender or transgender, whose behavior falls outside conventional gender norms. Furthermore, genderqueer, by virtue of its ties with queer culture, carries sociopolitical connotations that androgyny does not carry. For these reasons, some androgynes may find the label genderqueer inaccurate, inapplicable, or offensive. Androgyneity is considered by some to be a viable alternative to androgyn for differentiating internal (psychological) factors from external (visual) factors.[25]

Terms such as bisexual, heterosexual, and homosexual are less applicable to androgynous individuals who do not identify as men or women to begin with. Infrequently the words gynephilia and androphilia are used, and some describe themselves as androsexual. These words refer to the gender of the person someone is attracted to, but do not imply any particular gender on the part of the person who is feeling the attraction.

Androgyny in fashion

Throughout most of twentieth century Western history, social rules have restricted people's dress according to gender. Trousers were traditionally a male form of dress, frowned upon for women.[27] However, during the 1800s, female spies were introduced and Vivandières wore a certain uniform with a dress over trousers. Women activists during that time would also decide to wear trousers, for example Luisa Capetillo, a women's rights activist and the first woman in Puerto Rico to wear trousers in public.[28]

In the 1900s, starting around World War I traditional gender roles blurred and fashion pioneers such as Paul Poiret and Coco Chanel introduced trousers to women's fashion. The "flapper style" for women of this era included trousers and a chic bob, which gave women an androgynous look.[29] Coco Chanel, who had a love for wearing trousers herself, created trouser designs for women such as beach pajamas and horse-riding attire.[27] During the 1930s, glamorous actresses such as Marlene Dietrich fascinated and shocked many with their strong desire to wear trousers and adopt the androgynous style. Dietrich is remembered as one of the first actresses to wear trousers in a premiere.[30]

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the women's liberation movement is likely to have contributed to ideas and influenced fashion designers, such as Yves Saint Laurent.[31] Yves Saint Laurent designed the Le Smoking suit and first introduced in 1966, and Helmut Newton’s erotized androgynous photographs of it made Le Smoking iconic and classic.[32] The Le Smoking tuxedo was a controversial statement of femininity and has revolutionized trousers.

Elvis Presley, however is considered to be the one who introduced the androgynous style in rock'n'roll and made it the standard template for rock'n'roll front-men since the 1950s.[33] His pretty face and use of eye makeup often made people think he was a rather "effeminate guy",[34] but Elvis Presley was considered as the prototype for the looks of rock'n'roll.[33] The Rolling Stones, says Mick Jagger became androgynous "straightaway unconsciously" because of him.[34]

However, the upsurge of androgynous dressing for men really began after during the 1960s and 1970s. When the Rolling Stones played London's Hyde Park in 1969, Mick Jagger wore a white "man's dress" designed by British designer Mr Fish.[35] Mr Fish, also known as Michael Fish, was the most fashionable shirt-maker in London, the inventor of the Kipper tie, and a principal taste-maker of the Peacock revolution in men's fashion.[36] His creation for Mick Jagger was considered to be the epitome of the swinging 60s.[37] From then on, the androgynous style was being adopted by many celebrities.

During the 1970s, Jimi Hendrix was wearing high heels and blouses quite often, and David Bowie presented his alter ego Ziggy Stardust, a character that was a symbol of sexual ambiguity when he launched the album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and Spiders from Mars.[38] This was when androgyny entered the mainstream in the 1970s and had a big influence in pop culture. Another significant influence during this time included John Travolta, one of the androgynous male heroes of the post-counter-culture disco era in the 1970s, who starred in Grease and Saturday Night Fever.[39]

Continuing into the 1980s, the rise of avant-garde fashion designers like Yohji Yamamoto,[40] challenged the social constructs around gender. They reinvigorated androgyny in fashion, addressing gender issues. This was also reflected within pop culture icons during the 1980s, such as David Bowie and Annie Lennox.[41]

Power dressing for women became even more prominent within the 1980s which was previously only something done by men in order to look structured and powerful. However, during the 1980s this began to take a turn as women were entering jobs with equal roles to the men. In the article “The Menswear Phenomenon” by Kathleen Beckett written for Vogue in 1984 the concept of power dressing is explored as women entered these jobs they had no choice but to tailor their wardrobes accordingly, eventually leading the ascension of power dressing as a popular style for women.[42] Women begin to find through fashion they can incite men to pay more attention to the seduction of their mental prowess rather, than the physical attraction of their appearance. This influence in the fashion world quickly makes its way to the world of film, with movies like "Working Girl" using power dressing women as their main subject matter.

Androgynous fashion made its most powerful in the 1980s debut through the work of Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo, who brought in a distinct Japanese style that adopted distinctively gender ambiguous theme. These two designers consider themselves to very much a part of the avant-garde, reinvigorating Japanism.[43] Following a more anti-fashion approach and deconstructing garments, in order to move away from the more mundane aspects of current Western fashion. This would end up leading a change in Western fashion in the 1980s that would lead on for more gender friendly garment construction. This is because designers like Yamamoto believe that the idea of androgyny should be celebrated, as it is an unbiased way for an individual to identify with one's self and that fashion is purely a catalyst for this.

Also during the 1980s, Grace Jones, a singer and fashion model, gender-thwarted appearance in the 1980s, which startled the public. Her androgynous style inspired many and she became an androgynous style icon for modern celebrities.[44]

In 2016, Louis Vuitton revealed that Jaden Smith would star in their womenswear campaign. Because of events like this, gender fluidity in fashion is being vigorously discussed in the media, with the concept being articulated by Lady Gaga, Ruby Rose, and in Tom Hooper's film The Danish Girl. Jaden Smith and other young individuals, such as Lily-Rose Depp, have inspired the movement with his appeal for clothes to be non-gender specific, meaning that men can wear skirts and women can wear boxer shorts if they so wish.[45]

Alternatives

An alternative to androgyny is gender-role transcendence: the view that individual competence should be conceptualized on a personal basis rather than on the basis of masculinity, femininity, or androgyny.[46]

In agenderism, the division of people into women and men (in the psychical sense), is considered erroneous and artificial.[47] Agendered individuals are those who reject gender labeling in conception of self-identity and other matters.[48] [49][50][51] They see their subjectivity through the term person instead of woman or man.[48]:p.16 According to E. O. Wright, genderless people can have traits, behaviors and dispositions that correspond to what is currently viewed as feminine and masculine, and the mix of these would vary across persons. Nevertheless, it doesn't suggest that everyone would be androgynous in their identities and practices in the absence of gendered relations. What disappears in the idea of genderlessness is any expectation that some characteristics and dispositions are strictly attributed to a person of any biological sex.[52]

Contemporary trends

Androgyny has been gaining more prominence in popular culture in the early 21st century.[56] Both fashion industries[57] and pop culture have accepted and even popularised the "androgynous" look, with several current celebrities being hailed as creative trendsetters.

The rise of the metrosexual in the first decade of the 2000s has also been described as a related phenomenon associated with this trend. Traditional gender stereotypes have been challenged and reset in recent years dating back to the 1960s, the hippie movement and flower power. Artists in film such as Leonardo DiCaprio sported the "skinny" look in the 1990s, a departure from traditional masculinity which resulted in a fad known as "Leo Mania".[58] Musical stars such as Brett Anderson of the British band Suede, Marilyn Manson and the band Placebo have used clothing and makeup to create an androgyny culture throughout the 1990s and the first decade of the 2000s.[59]

While the 1990s unrolled and fashion developed an affinity for unisex clothes there was a rise of designers who favored that look, like Helmut Lang, Giorgio Armani and Pierre Cardin, the trends in fashion hit the public mainstream in the 2000s (decade) that featured men sporting different hair styles: longer hair, hairdyes, hair highlights. Men in catalogues started wearing jewellery, make up, visual kei, designer stubble. These styles have become a significant mainstream trend of the 21st century, both in the western world and in Asia.[60] Japanese and Korean cultures have featured the androgynous look as a positive attribute in society, as depicted in both K-pop, J-pop,[61] in anime and manga,[62] as well as the fashion industry.[63]

See also

- List of androgynous people

- Bigender

- Epicenity

- Futanari

- Gender bender

- Gender dysphoria

- Gender neutrality

- Gonochorism

- Gynandromorph

- Gynomorph

- Hermaphrodite

- List of transgender-related topics

- Non-binary gender

- Pangender

- Postgenderism

- Sexual Orientation Hypothesis

- Soft butch

- Third gender

- Transsexualism

- Trigender

- True hermaphroditism

References

- "Online Etymology Dictionary: androgynous". Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- Leick, Gwendolyn (2013) [1994]. Sex and Eroticism in Mesopotamian Literature. New York City, New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-92074-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roscoe, Will; Murray, Stephen O. (1997). Islamic Homosexualities: Culture, History, and Literature. New York City, New York: New York University Press. pp. 65–66. ISBN 0-8147-7467-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The Symposium: and, The Phaedrus; Plato's erotic dialogues. Translated and with introduction and commentaries by William S. Cobb. Albany: State University of New York Press. 1993. ISBN 978-0-7914-1617-4.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Androgyn". University of Michigan Library. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- van der Lugt, Maaike, "Sex Difference in Medieval Theology and Canon Law," Medieval Feminist Forum (University of Iowa) vol. 46 no. 1 (2010): 101–121

- Hauck, Dennis William (2008). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Alchemy. New York: Alpha Books. ISBN 9781592577354. OCLC 176917711.

- Atkinson, William Walker (2012). Marsh, Clint (ed.). The Secret Doctrine of the Rosicrucians. San Francisco, CA: Weiser Books. pp. 52–61. ISBN 9781578635344. OCLC 792888485.

- Rosicrucian Order, AMORC (13 December 2011). "Rosicrucian Prophecies" (PDF). rose-croix.org. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- Ellis, Eugenia Victoria (June 2004). “Geomantic Mathematical (re)Creation: Magic Squares and Claude Bragdon's Theosophic Architecture”. Nexus V: Architecture and Mathematics: 79-92.

- William Wallace Atkinson, The Secret Doctrines of the Rosicrucians (London: L.N. Fowler & Co., 1918), 53-54.

- "Solar System Symbols". Solar System Exploration: NASA Science. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/androgyny

- http://www.isna.org/faq/what_is_intersex

- Cook, Ellen Piel (1985). Psychological Androgyny. Pergamon Press. ISBN 0-08-031613-1.

- Sargent, Alice G. (1981). The Androgynous Manager. New York: AMACOM. ISBN 0-8144-5568-9.

- Rogers, Kara (6 February 2009). "Androgyny". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- Gartzia, Leire; Pizzaro, Jon; Baniandres, Josune. "Emotional Androgyny: A Preventive Factor of Psychosocial Risks at Work?". Frontiers in Psychology. 9 – via PMC.

- Kaufman, Scott Barry (1 September 2013). "Blurred Lines, Androgyny and Creativity". Scientific American Blog Network. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- Santrock, J. W. (2008). A Topical Approach to Life-Span Development. New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies. 007760637X

- DeFrancisco, Victoria L. (2014). Gender in Communication. SAGE Publications. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-4522-2009-3.

- Choi, N. (2004). Sex role group differences in specific, academic, and general self-efficacy. Journal of Psychology, 138, 149–159.

- Woodhill, Brenda; Samuels, Curtis (2004). "DESIRABLE AND UNDESIRABLE ANDROGYNY: A PRESCRIPTION FOR THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY". Journal of Gender Studies. 13: 15–28. doi:10.1080/09589236.2004.10599911.

- https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/genderqueer

- "Psychological Androgyny -- A Personal Take". Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- New world coming: the 1920s and the making of modern America. New York: Scribner, 2003, p. 253, ISBN 978-0-684-85295-9.

- Ewing, E.; Mackrell, A. (2002). History of Twentieth Century Fashion. LA: Quite Specific Media Group Ltd.

- Valle-Ferrer, Norma (1 June 2006). Luisa Capetillo, Pioneer Puerto Rican Feminist: With the collaboration of students from the Graduate Program in Translation, The University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras, Spring 1991. Peter Lang Publishing Inc. ISBN 9780820442853.

- Köksal, Duygu; Falierou, Anastasia (10 October 2013). A Social History of Late Ottoman Women: New Perspectives. BRILL. ISBN 9789004255258.

- "Harriet Fisher". The Queen of Androgyny – Marlene Dietrich – Blog. Archived from the original on 16 June 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- Commentator, Sally Kohn, CNN Political. "The Seventies: The sex freakout". CNN. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- Moet, Sophie (1 May 2014). "Androgyny and Feminism". Sophie Moet. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- "Elvis Never Gets Credit for One of His Greatest Gifts to Rock 'n Roll". Observer. 8 January 2016. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- Daniel, Pete (1 January 2000). Lost Revolutions: The South in the 1950s. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807848487.

- Baker, Lindsay. "His or hers: Will androgynous fashion catch on?". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- Elan, Priya (13 March 2016). "Peacock revolution back with label that dressed Mick Jagger and David Bowie". The Guardian. London.

- "Mick Jagger's white dress cast him as a romantic hero". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- Lalovic, Itana (19 November 2013). "Androgyny in the fashion world". Wall Street International. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- Rehling, Nicola (21 June 2010). Extra-Ordinary Men: White Heterosexual Masculinity and Contemporary Popular Cinema. Lexington Books. ISBN 9781461633426.

- "Global Influences: Challenging Western Traditions". London: Berg.

- Andrew Anthony (10 October 2010). "Annie Lennox: the interview". The Observer. London, UK. Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- "The Menswear Phenomenon". Vogue; Conde Nast.

- "Global Influences: Challenging Western Traditions". London: Berg.

- "Androgynous Fashion Moments". Highsnobiety. 14 May 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- "Gender Fluidity in the Fashion Industry". Cub Magazine. 8 February 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Pleck, J. H. (1995). The gender-role strain paradigm. In R. F. Levant & W. S. Pollack (Ed.s), A new psychology of men. New York: Basic Books.

- Butler, Judith P. (1993). Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of 'Sex'. New York: Routledge. pp. 2–3. ISBN 9780415903660. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- Galupo, M. Paz; Pulice-Farrow, Lex; Ramirez, Johanna L. (2017). "Like a Constantly Flowing River": Gender Identity Flexibility Among Nonbinary Transgender Individuals. pp. 163–177. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-55658-1_10. ISBN 978-3-319-55656-7.

- Johanna Schorn. "Taking the "Sex" out of Transsexual: Representations of Trans Identities in Popular Media" (PDF). Inter-Disciplinary.Net. Universität zu Köln. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 October 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- Galupo, M. Paz; Henise, Shane B.; Davis, Kyle S. (2014). "Transgender microaggressions in the context of friendship: Patterns of experience across friends' sexual orientation and gender identity". Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 1 (4): 462. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.708.6228. doi:10.1037/sgd0000075.

- Sumerau, J. E.; Cragun, R. T.; Mathers, L. A. B. (2015). "Contemporary Religion and the Cisgendering of Reality". Social Currents. 3 (3): 2. doi:10.1177/2329496515604644.

- Erik Olin Wright (2011). "In defense of genderlessness (The Sex-Gender Distinction)". In Axel Gosseries, Philippe Vanderborght (ed.). Arguing about justice. Louvain: Presses universitaires de Louvain. pp. 403–413. ISBN 9782874632754. Retrieved 6 February 2017.

- Ian Chapman, Henry Johnson, ed. (2016). Global Glam and Popular Music: Style and Spectacle from the 1970s to the 2000s. Routledge. pp. 203–205. ISBN 9781317588191.

- "Move over, Psy! Here comes G-Dragon style". The Independent. 17 August 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- "K-pop: a beginner's guide". The Guardian. 3 March 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- "Androgyny becoming global?". uniorb.com. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- Wendlandt, Astrid. "Androgynous look back for spring". Reuters. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- Peter Hartlaub (24 February 2005). "The teenage fans from 'Titanic' days jump ship as Leonardo DiCaprio moves on". sfgate.com. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- Cavendish, Marshall (2010). Sex and Society, Vol 1. Paul Bernabeo. p. 69.

- "Androgynous look catches on". The Himalayan Times. 13–16 September 2010. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- "Harajuku Girls Harajuku Clothes And Harajuku Gothic fashion Secrets". Tokyo Top Guide. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- "Profile of Kagerou". jpopasia.com. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- Webb, Martin (13 November 2005). "Japan Fashion Week in Tokyo 2005. A stitch in time?". The Japan Times. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

External links

| Look up androgyny in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Androgyny. |

- Androgyny: study and collection of articles

- Androgyne Online

- Sandra Bem and androgyny

- The Two-Spirit Tradition

- "Hormone replacement therapy", Wikipedia, 27 January 2020, retrieved 17 February 2020

- How Androgyny Works (Part 1) Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- The Measurement of Psychological Androgyny Bem, S. L. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42(2), 155–162. retrieved February 17, 2020