Arden of Faversham

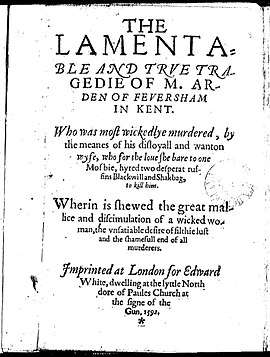

Arden of Faversham (original spelling: Arden of Feversham) is an Elizabethan play, entered into the Register of the Stationers Company on 3 April 1592, and printed later that same year by Edward White. It depicts the murder of Thomas Arden by his wife Alice Arden and her lover, and their subsequent discovery and punishment. The play is notable as perhaps the earliest surviving example of domestic tragedy, a form of Renaissance play which dramatized recent and local crimes rather than far-off and historical events.

The author is unknown, and the play has been attributed to Thomas Kyd, Christopher Marlowe, and William Shakespeare, solely or collaboratively, forming part of the Shakespeare Apocrypha. The use of computerized stylometrics has kindled academic interest in determining the authorship. The 2016 edition of The Oxford Shakespeare attributes the play to Shakespeare together with an anonymous collaborator, and rejects the possibility of authorship by Kyd or Marlowe.[1]

It has also been suggested that it may be the work of Thomas Watson with contributions by Shakespeare.[2][3]

Sources

.jpg)

Thomas Arden, or Arderne, was a successful businessman in the early Tudor period. Born in 1508, probably in Norwich, Arden took advantage of the tumult of the Reformation to make his fortune, trading in the former monastic properties dissolved by Henry VIII in 1538. In fact, the house in which he was murdered (which is still standing in Faversham) was a former guest house of Faversham Abbey, the Benedictine abbey near the town. His wife Alice had taken a lover, a man of low status named Mosby; together, they plotted to murder her husband. After several bungled attempts on his life, two ex-soldiers from the former English dominion of Calais known as Black Will and Shakebag were hired and continued to make botched attempts.[4] Arden was finally killed in his own home on 14 February 1551, and his body was left out in a field during a snowstorm, in the hope that the blame would fall on someone who had come to Faversham for the St Valentine's Day fair. The snowfall stopped, however, before the killers' tracks were covered, and the tracks were followed back to the house. Bloodstained swabs and rushes were found, and the killers quickly confessed. Alice and Mosby were put on trial and convicted of the crime; he was hanged and she burnt at the stake in 1551. Black Will may also have been burnt at the stake after he had fled to Flanders: the English records state he was executed in Flanders, while the Flemish records state he was extradited to England. Shakebag escaped and was never heard of again. Other conspirators were executed and hanged in chains. One – George Bradshaw, who was implicated by an obscure passage in a sealed letter he had delivered – was wrongly convicted and posthumously acquitted.

The story would most likely have been known to Elizabethan readers through the account in Raphael Holinshed's Chronicles, although the murder was so notorious that it is also possible that it was in the living memory of some of the anonymous playwright's acquaintances.

Both the play and the story in Holinshed's Chronicles were later adapted into a broadside ballad, "The complaint and lamentation of Mistresse Arden of Feversham in Kent".[5]

Main characters

- Thomas Arden: Thomas Arden was a self-made man, he was formerly the mayor of Faversham and was appointed as the king's controller of imports and exports. Arden made his will in the December before his death

- Alice Arden: Wife of Thomas Arden, Alice plots with her lover Mosby to kill Arden. Alice is shown to believe love transcends social class

- Mosby: Alice's lover and brother of Susan, Alice's maid

- Black Will and Shakebag: Hired murderers. In the play the pair fail a number of times to carry out the murder of Arden. Shakebag is shown to be the more evil of the two.

- Franklin: Thomas Arden's best friend and traveling companion. On the road from London, he begins telling a tale of female infidelity.

Text, history and authorship

The play was printed anonymously in three quarto editions during the period, in 1592 (Q1), 1599 (Q2), and 1633 (Q3). The last publication occurred in the same year as a broadsheet ballad written from Alice's point of view. The title pages do not indicate performance or company. However, the play was never fully forgotten. For most of three centuries, it was performed in George Lillo's adaptation; the original was brought back to the stage in 1921, and has received intermittent revivals since. It was adapted into a ballet at Sadler's Wells in 1799, and into an opera, Arden Must Die, by Alexander Goehr, in 1967.

In 1656 it appeared in a catalogue (An Exact and perfect Catalogue of all Plaies that were ever printed) with apparent mislineation. It has been argued that attributions were shifted up one line; if this is true, the catalogue would have attributed Arden to Shakespeare.[6]

The question of the text's authorship has been analyzed at length, but with no decisive conclusions. Claims that Shakespeare wrote the play were first made in 1770 by the Faversham antiquarian Edward Jacob. Others have also attributed the play to Shakespeare, for instance Algernon Charles Swinburne, George Saintsbury, and the nineteenth-century critics Charles Knight and Nicolaus Delius. These claims are based on evaluations of literary style and parallel passages.

Christopher Marlowe has also been advanced as an author or co-author. The strong emotions of the characters and the lack of a virtuous hero are certainly in line with Marlowe's practice. Moreover, Marlowe was raised in nearby Canterbury and is likely to have had the knowledge of the area evinced by the play. Another candidate, favored by critics F. G. Fleay, Charles Crawford, H. Dugdale Sykes, and Brian Vickers, is Thomas Kyd, who at one time shared rooms with Marlowe.

Debates about the play's authorship involve the questions of: (a) whether the text was generated largely by a single writer; and (b) which writer or writers may have been responsible for the whole or parts. In 2006, a new computer analysis of the play and comparison with the Shakespeare corpus by Arthur Kinney, of the Massachusetts Center for Renaissance Studies at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in the United States, and Hugh Craig, director of the Centre for Linguistic Stylistics at the University of Newcastle in Australia, found that word frequency and other vocabulary choices were consistent with the middle portion of the play (scenes 4–9) having been written by Shakespeare.[7] This was countered in 2008, when Brian Vickers reported in the Times Literary Supplement that his own computer analysis, based on recurring collocations, indicates Thomas Kyd as the likely author of the whole.[8] In a study published in 2015, MacDonald P. Jackson set out an extensive case for Shakespeare's hand in the middle scenes of Arden, along with selected passages from earlier in the play.[9]

In 2013 the RSC published an edition attributing the play, in part, to William Shakespeare. Shakespeare had an ancestor named Thomas Arden on his mother's side, but he died in 1546 (four years prior to the Thomas Arden in the play) in Evenley, Rutland.

Modern performance

- In 1955 the play was performed by Joan Littlewood's Theatre Workshop at the Paris International Festival of Theatre as the English entry.

- In 1970 Buzz Goodbody directed a version for the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC), with Emrys James as Arden and Dorothy Tutin as Alice, at The Roundhouse.

- In 1982 Terry Hands directed the work, with Bruce Purchase and Jenny Agutter, at the RSC's Other Place theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon.

- In 2001 the play was performed for a summer season in the garden of Arden's house in Faversham, the scene of the murder.

- In 2004, the play was performed by the Metropolitan Playhouse of New York.[10]

- In 2010 the play was performed at the Rose Theatre in Bankside by Em-lou productions. Directed by Peter Darney, it was its first London run for a decade.[11]

- In 2014, the Royal Shakespeare Company performed a production of the play; it ran at the Swan Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon.[12]

- In 2015, the play was performed by the Brave Spirits Theatre at Atlas Performing Arts Center.[13]

- In 2015, the play received a new interpretation by the Hudson Shakespeare Company of New Jersey as it was moved from the 1500s to the 1950s as part of their Shakespeare in the parks series. The production was notable for matching the farcical plot with 1950s pop songs by Sinatra, Elvis, Patsy Cline, and Fats Domino and making Arden's friend Franklin a woman, playing up sexual subtext inherent in their scenes.[14]

- In May 2018, Maiden Thought Theatre performed it in their home town of Bremen (Germany), setting it to original music by Frances Byrd as a homage to the genre of Film Noir, playing out more of the comedic elements of the play. They, too, changed the role of Franklin to a female "Frankie", while setting up Faversham (restoring the original spelling, "Feversham") as a morally and deeply corrupt society.[15]

- In 2019, the play was performed on BBC Radio 3 (UK) with Ewan Bailey as Arden and Amaka Okafor as Alice, adapted and directed by Alison Hindell.[16]

Notes

- "Christopher Marlowe credited as one of Shakespeare's co-writers". theguardian.com.

- Dalya Alberge (5 April 2020). "Shakespeare's secret co-writer finally takes a bow … 430 years late". The Guardian.

- Taylor, Gary (11 March 2020). "Shakespeare, Arden of Faversham, and Four Forgotten Playwrights". The Review of English Studies. doi:10.1093/res/hgaa005.

- Raphael Holinshed, Chronicles of England, Scotland and Ireland, p. 1027

- Facsimiles and recordings of the ballad can be found on the English Broadside Ballad Archive.

- W. W. Greg, "Shakespeare and Arden of Feversham", The Review of English Studies, 1945, os-XXI(82):134–136.

- Craig H., Kinney, A., Shakespeare, Computers, and the Mystery of Authorship, Cambridge University Press, 2012, pp. 78–99.

- Brian Vickers, "Thomas Kyd, Secret Sharer", The Times Literary Supplement, 18 April 2008, pp. 13–15.

- Jackson, MacDonald P. (2015). Determining the Shakespeare Canon: 'Arden of Faversham' and 'A Lover's Complaint'. Cambridge: Cambridge. ISBN 978-0198704416.

- Bly, Mary. "Reviews – The Lamentable and True Tragedy of Master Arden of Faversham". Metropolitan Playhouse.

- Quarmby, Kevin (n.d.). "Theatre review: Arden of Faversham at Rose Theatre, Bankside". British Theatre Guide. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 June 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Hill, Heather. "Theatre Review: Arden of Faversham by Brave Spirits Theatre at Atlas Performing Arts Center". Maryland Theater Guide.

- "Shakespeare's 'The Murder of Thomas Arden of Faversham' coming to Kenilworth Library, July 20". NJ.com. Suburban News. 15 July 2015.

- "Arden of Feversham". 16 October 2017.

- "Drama on 3, Arden of Faversham". BBC Radio 3.

References

- Arden of Feversham: a study of the Play first published in 1592 (1970) written and illustrated by Anita Holt

- C. F. Tucker Brooke, ed., The Shakespeare Apocrypha, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1908.

- Max Bluestone, "The Imagery of Tragic Melodrama in Arden of Faversham," in Bluestone and Rabkin (eds.), Shakespeare's Contemporaries, 2nd ed., Prentice-Hall, 1970.

- Catherine Belsey. "Alice Arden's Crime." Staging the Renaissance. Ed. David Scott Kastan and Peter Stallybrass. New York: Routledge, 1991.

- Lena Cowen Orlin. Private Matter and Public Culture in Post Reformation England (especially Chapter One). Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1994.

External links

- Edition of the play in Brooke's Shakespeare Apocrypha

- Abridged modernized online text of the play (William Harris, Middlebury College)

- The RSC Shakespeare – "The text of Shakespeare's possible scene, a plot summary for the whole play and a brief introduction by Jonathan Bate."

- Account of the execution of the murderers in The Newgate Calendar.

- The complaint and lamentation of Mistresse Arden of Feversham in the English Broadside Ballad Archive. University of California, Santa Barbara. (Includes ballad facsimile, text, and MP3 recording of the ballad sung unaccompanied)

.png)