Sonnet 56

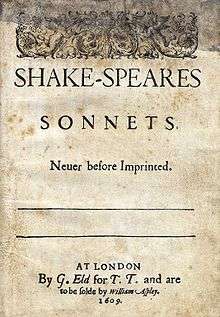

Sonnet 56 is one of 154 sonnets written by the English playwright and poet William Shakespeare. It's a member of the Fair Youth sequence, in which the poet expresses his love towards a young man. The exact date of its composition is unknown, it is thought that the Fair Youth sequence was written in the first half of the 1590s and was published with the rest of the sonnets in the 1609 Quarto.[2]

| Sonnet 56 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

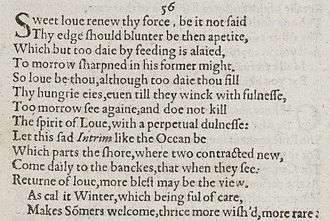

Sonnet 56 in the 1609 Quarto | |||||||

| |||||||

Structure

While "sonnet" originally referred to any short lyric,[3] the English (or Surreyan or Shakespearean) sonnet has a definite form. The English sonnet contains three quatrains followed by a rhyming couplet. It follows the form's typical rhyme scheme, ABAB CDCD EFEF GG, and is written in iambic pentameter, a type of poetic metre based on five pairs of metrically weak/strong syllabic positions. The fourth line exemplifies a regular iambic pentameter:

× / × / × / × / × / To-morrow sharpened in his former might: (56.4)

The meter demands a few variant pronunciations: Line six's "even" functions as one syllable, line eight's "spirit" as one and "perpetual" as three, line nine's "interim" as two, and line thirteen's "being" as one.

Two lines have a final extrametrical syllable or feminine ending, as exemplified by line eight:

× / × / × / × / × / (×) The spirit of love, with a perpetual dulness. (56.8)

- / = ictus, a metrically strong syllabic position. × = nonictus. (×) = extrametrical syllable.

Context

Sonnet 56 is part of the Fair Youth sequence.[2] This sequence spans sonnets 1-126. Furthermore, the first 77 sonnets are called the "Procreation" section, the rest 78-126 the "Rival Poet" and 127-154 is the "Dark Lady" section. In the Fair Youth section Shakespeare details his feelings towards the young man that he is in love with.[4] This sonnet was published along with the rest in 1609 in Quarto. There is a debate as to why the sonnets were published in 1609. One theory affirmed by Duncan-Jones, is that these sonnets were published in order to "put right the wrong done" by the unauthorized publishing by Jaggard in 1599.[5] They are thought to have been written long before the publication in 1609. Some researchers have used clues from Sonnet 107 with its allusions to Queen Elizabeth to date it to 1596. If the sonnets were written in the order that they appear in Quarto, then it is plausible that some were written before 1596.[4]

Sonnet 56 remained popular enough that even after four centuries contemporaries are still studying it. One such person is Paul Hoover, who released a book of poetry based on Sonnet 56, entitled "Sonnet 56." [6]

Exegesis

Overview

Sonnet 56 is part of the Fair Youth sonnets.[7] The sonnet's first line was inspired by George Whetstone's The Rocke of Regard (1576).[8] The sonnet is divided up into four quatrain, groups of four lines, and a couplet.[3] Sonnet 56 is puzzling because of its seemingly inappropriate placement next to Sonnet 55. In Sonnet 55, the poet's relationship with the young man is steady and secure, but here there is a sudden shift from confidence to deep insecurity.[9] In this sonnet the poet examines the "quality of love." It is not clear whose love is being addressed. The poet's, "his friend's, or that of both?" The poet "pleads for the love to be charged with fresh vigor." At the same time, the poet suggests that a "separation" may be what the relationship needs in order to "renew the intensity of their devotion." It should noted that the identity of the "Sweet love" is not located in the poem and the ultimate fate of the relationship is left ambiguous.[3] Although, there may be clues of their fate in the rest of the Fair You Sonnets.[7] Shakespeare also uses metaphors for eating to talk about a sexual appetite.[3]

As the poet implores "Sweet love" (1) to conquer the lust that is ruining his union with the young man. This analysis of the sonnet relies upon two assumptions: 1) the young man is the poet's lover and 2) that when the poet refers to "sad interim" (9), he does not mean that the young man is away from London, but that he is separated from him emotionally - i.e., they are in a "period of estrangement" from one another due to the young man's promiscuity. Thus the poet is "whipping up the young man's flagging affection. Behind lines 9-12 flickers a reminiscence of the situation of Hero and Leander" (Rowse 115). The situation becomes even more clear when we read Sonnet 57, in which the poet, now very worried about the young man's lustful nature, asks him outright, "Being your slave, what should I do but tend/Upon the hours and times of your desire? ... dare I question with my jealous thought/Where you may be" (1-2/9-10).[9]

The poet also muses how love in the states of "sharpness" and "dullness" is boring.[6]

Quatrain 1

The first quatrain details the love that the poet feels. The first line addresses "the quality of love." [3] Shakespeare also wants his love to be noticed and to the "desired" effect to happen.[8] The use of "sweet love" appears to address a specific person but later seems to address the love that the author feels.[9] The writer also questions whether or not this love is dying and doesn't want it to be spoken.[9] According to Duncan-Jones, the use of "than appetite" in line two and the use of "feeding" in line three suggests a "sexual appetite" because of the topic of love. Sexual appetite is more common in Shakespeare's works than "the application of food." [3][6] In this quatrain, Shakespeare also "admonishes" the youth that inspired this sonnet and wants to "return" to writing his praises.[8] Shakespeare manages to present all of this without sounding too "confrontational."[10]

Quatrain 2

Line five features "So, love, be thou;" gives a personal feeling to the person that is being addressed. This encourages the addressee to be thought of as a "human individual." The subject of the line still seems to be "'the emotion of love"' and the owner of the love still remains unclear. The use of the word "wink" in line six reinforces the appetite and feeding metaphor.[3] This reinforces the idea that the poet is addressing the "youth" about their love.[9] A "wink" closes the eyes like "two mouths" and so the winker is eating the "sight of the beloved that they shut themselves against further cramming" "Dullness" is likely referencing a sexual lethargy.[3]

Quatrain 3

The use of "interim" in line nine represents the time where Shakespeare would have to deal with inactivity or absence. This suggests that the "sad interim" is caused by "the young man's withdrawal." Line nine says "Let this sad interim like the ocean be" and line ten continues with "Which parts the shore, where two contracted new." Line nine and ten appears to conjure an image where the poet and his lover are on opposite sides of a shore but it is not tragic like in other applications.[3] Instead the allusion the Shakespeare makes is that he and his friend are like a married couple.[11] Lines eleven and twelve supports this: "Come daily to the banks, that when they see" "Return of love, more blessed be the view." The "betrothed lovers" are likened to gazing daily at each other and are "rewarded" by either seeing each other or a "fresh meeting." [3]

Couplet

Shakespeare uses "or" in line thirteen's "Or call it winter, which being full of care" in order to signal that an analogy is coming. However, using "or" is not the best way to do so as it "cannot readily introduce the sense" that is "required." Winter is used to represent the "misery" and the "absence" the poet feels. Winter being used to represent misery or absence is nothing new. "Summer's welcome" refers to the "eagerness" in the way people welcome spring. This welcome is considered "rare" or precious since it is uncommon yet still "wished" for.[3]

Further reading

This sonnet is also the inspiration behind Paul Hoover's 2009 book of poetry, "Sonnet 56," in which Hoover translates the sonnet into 56 written forms, including an answering machine transcript, tanka and confessional poem.[6]

References

- Pooler, C[harles] Knox, ed. (1918). The Works of Shakespeare: Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare [1st series]. London: Methuen & Company. OCLC 4770201.

- Shakespeare, William (2012). Shakespeare's Sonnets: An Original-Spelling Text. New York: Oxford. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-19-964207-6.

- Duncan-Jones, Katernine (2010). Shakespeare's Sonnets (Revised Edition). London: Arden Shakespeare. p. 58. ISBN 1-4080-1797-0.

- Fort, J.A. (1933). "The Order and Chronology of Shakespeare's Sonnets" (PDF). Review of English Studies. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine (2010). Shakespeare's Sonnets (Revised Edition). London: Arden Shakespeare. pp. 1–3. ISBN 1-4080-1797-0.

- Hoover, Paul. Sonnet 56. Les Figures Press. ISBN 978-1-934254-12-7.

- Pequigney, Joseph (1986). Such is My Love. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 123.

- Daugherty, Leo (2014). "A Previously Unreported Source for Shakespeare's Sonnet 56". Notes and Queries. doi:10.1093/notesj/gju013. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- "Analysis of Sonnet 56 and Plain English Paraphrase". www.shakespeare-online.com. Retrieved 2015-09-24.

- Risher, Renee (2010). "Re, Repeat, Re-ensure". American Book Review. 31 (3): 29. eISSN 2153-4578. ISSN 0149-9408 – via Project MUSE.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vedler, Helen (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Further reading

- First edition and facsimile

- Shakespeare, William (1609). Shake-speares Sonnets: Never Before Imprinted. London: Thomas Thorpe.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1905). Shakespeares Sonnets: Being a reproduction in facsimile of the first edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 458829162.

- Variorum editions

- Alden, Raymond Macdonald, ed. (1916). The Sonnets of Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 234756.

- Rollins, Hyder Edward, ed. (1944). A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets [2 Volumes]. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. OCLC 6028485.

- Modern critical editions

- Atkins, Carl D., ed. (2007). Shakespeare's Sonnets: With Three Hundred Years of Commentary. Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4163-7. OCLC 86090499.

- Booth, Stephen, ed. (2000) [1st ed. 1977]. Shakespeare's Sonnets (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale Nota Bene. ISBN 0-300-01959-9. OCLC 2968040.

- Burrow, Colin, ed. (2002). The Complete Sonnets and Poems. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192819338. OCLC 48532938.

- Duncan-Jones, Katherine, ed. (2010) [1st ed. 1997]. Shakespeare's Sonnets. The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series (Rev. ed.). London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4080-1797-5. OCLC 755065951.

- Evans, G. Blakemore, ed. (1996). The Sonnets. The New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521294034. OCLC 32272082.

- Kerrigan, John, ed. (1995) [1st ed. 1986]. The Sonnets ; and, A Lover's Complaint. New Penguin Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-070732-8. OCLC 15018446.

- Mowat, Barbara A.; Werstine, Paul, eds. (2006). Shakespeare's Sonnets & Poems. Folger Shakespeare Library. New York: Washington Square Press. ISBN 978-0743273282. OCLC 64594469.

- Orgel, Stephen, ed. (2001). The Sonnets. The Pelican Shakespeare (Rev. ed.). New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0140714531. OCLC 46683809.

- Vendler, Helen, ed. (1997). The Art of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-63712-7. OCLC 36806589.

.png)