Trimontium (Newstead)

Trimontium is a Roman fort complex in Scotland.[1] Located at Newstead, near Melrose, in the Scottish Borders, in view of the three Eildon Hills (Latin: trium montium, three hills), it is a remarkable site that still has much to reveal. Identified by Ptolemy in his Geography,[2] the location of Trimontium, sixty miles north of Hadrian's Wall, means that the fort's position and status was constantly changing.[3] Between c.80AD and c.180AD the expansion, consolidation & retreat of the Roman presence in Caledonia, as it pushed further north to the Antonine Wall & beyond,[4] and retreated back south of Hadrian's Wall, led to consequential changes in the role, fortunes and focus of Trimontium.

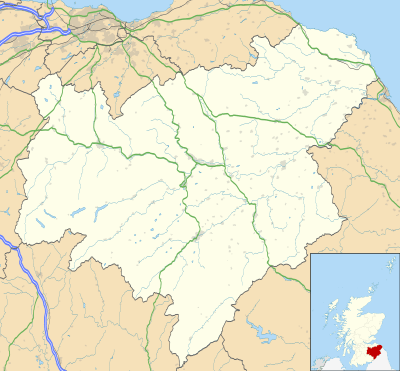

| Trimontium | |

|---|---|

Site of Trimontium with the three peaks of the Eildon Hills in the background | |

| |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 55.601°N 2.687°W |

| Town | Melrose |

| County | Scottish Borders |

| Country | Scotland |

| Reference | |

| UK-OSNG reference | NT569344 |

The Fort

It took the Romans less than four decades, from the invasion of 43AD and subsequent conquest of southern & eastern Britain, followed by expansion into northern England and Wales, for them to be knocking on the door of the northern expanses of Caledonia. Their next challenge was to press northwards into southern Scotland.[1]

The fort at Trimontium sits on the banks of the River Tweed, with the Eildon Hills and the Iron Age hillfort atop Eildon North a visible reminder of both the local population and imposing landscape of the Scottish Borders. With the rivers Tweed and the Leader both providing routes for the movement of goods and people, and with the Roman road that became Dere Street passing alongside the fort, the location was ideal.[5]

The fort's fortunes mirrored that of the Roman expansion and retreat in the area, as its role swung from frontier post to supply and logistical waypoint. From its first construction phase in c.80AD through to the last occupation and retreat shortly after 180AD the fort would have been a focal point and center of activity for both Romans and locals alike. The local Iron Age population, living in family farmsteads across the region, and gathering at times within the network of hillforts across the landscape would have had to develop a range of strategies to exist within or alongside the Roman presence. These could vary from alliance and trade to dispute and warfare.[1]

The fort was constructed in multiple phases. Dr Simon Clarke of Bradford University has produced a logical sequence of building and destruction for the fort and its annexes. This was managed by combining evidence from the first excavations of James Curle (1905–1910) and Sir Ian Richmond (1947) with aerial photographs and modern search and rescue excavations of Bradford University (1987–1997)[6]

Phase 1 (c.79-87AD): The earliest occupation of the site was the irregular Agricolan fort established c.80AD. It had a turf rampart on a cobble foundation with two ditches in front of it, overlapping each entrance. On the west side was an annexe which was also defended by a similar rampart and ditches arrangement.[7]

Phase 2 (c.90-105AD): After a possible short abandonment of the fort the Romans were back, and building in strength. Old ditches were filled in and new defences constructed. This resulted in a colossal strengthening of the fort. The new turf rampart was built on a cobble base which measured 13.5m across and around 8.4m high. In front of this was a single ditch between 5 & 7m wide and 2 to 4m deep. New, well defended annexes appear on the south, east and probably north sides of the fort, inhabited by civilians and camp followers.[7]

Phase 3 (c.105-137AD): Trimontium was deserted as the Roman occupiers retreated south of Hardrian's Wall.

Phase 4 (c.137-139AD): Dr. Clarke suggests that evidence points to the possibility that the fort was reoccupied a few year prior to the 140AD advances into Caledonia by Emperor Antoninus Pius. If this is the case it stands that the fort would have been a formidable outpost beyond Hadrian's Wall, with a civilian population within the annexes. Excavations and modern archaeology show the main entrance is now positioned through the southern annexe.[7]

Phase 5 (c.140-158AD): As the Roman presence pressed northwards and work began on the Antonine Wall (from 142AD), the role for Trimontium changed. It was reduced in size with the building of a 2m thick masonry wall through the main fort, though at the same time stone was used in the rebuilding. Manufacturing was becoming an important role for this newly purposed supply and logistics centre. Now behind the front line it is believed that the civilian population attached to the fort may have numbered some 2-3,000.[8]

Phase 6 (c.160AD): Around this time the previous construction of the sub-dividing wall was removed as Trimontium's role changed from supply & manufacture to a front line fort due in part to the abandonment of the Antonine Wall. Within the fort a long, narrow barrack block was constructed and evidence points to a large decrease in the civilian population surrounding the fort.[8]

Phase 7 (c.160-184AD): As the civilian population surrounding and supporting the fort diminished further the land that housed the annexes returned to a more natural state. The military presence reduced further, with the barrack block now housing the remaining soldiers and their families. The evidence points to the fort being deserted some time around 180AD. It is unclear whether the remaining civilian population left at this time or remained, outside or even inside the fort. Evidence does point to the potential use of early 3rd and late 4th century coins in the area (coins have been found to the south and to the west of Newstead village). Were the local population still engaged in a Romanised trade and economic pattern of behaviour?[8]

Evidence drawn from the site indicate the presence of a considerable cavalry contingent at Trimontium. The list of such archaeological finds is extensive and includes horse skeletons, multiple parts of horse tack or harnesses, outstanding decorated cavalry parade helmets & face masks[9] that can be seen at NMS Edinburgh, and intriguingly the prospect of a gyrus, or training ring.[10]

During these phases of occupation, the population of the fort varied considerably, the permanent garrison level was probably around 1000 - this number though would be complemented by the trades, manufacturers, craftsmen and families associated with the camp during the different phases of occupation. It has been estimated that the number could have risen to anywhere between 2000-5000.[9]

Site archaeology

The earliest modern reference to the archaeological significance of Trimontium stems from finds uncovered during mid-Victorian railway cutting works as part of the Waverley Line construction in 1846. As land to the east of the village of Newstead was worked, finds from pits crammed full of Roman artefacts were uncovered.[11]

Excavations by James Curle between February 1905 and September 1910 began the first exploration of the site, making many findings.[12] These include foundations of successive forts described earlier, which throw much light on the character of this unique Roman military site, an unparalleled collection of Roman armour, including ornate cavalry parade (or 'sports') helmets, horse fittings including bronze saddleplates and studded leather chamfrons, numerous artetfacts associated with trade and manufacture, building & construction and daily life on the Roman frontier. In 1911 Curle published his archaeological findings in 'A Roman Frontier Post and its People'. This remarkable volume quickly became a standard reference work, ahead of its time and still the most decisive work published in Scotland covering this period of Roman occupation, expansion & retreat.[11]

Sir Ian Richmond undertook small scale excavations and some re-interpretations of Curle's work in 1947. At this time, with the advent and development of aerial photography as a tool in modern archaeological research, Dr J.K. St Joseph's work at Trimontium revealed up to nine temporary encampments, evidenced through cropmarkings.[11]

In 1989 The Newstead Project began, a 5-year archaeological investigation undertaken by the Department of Archaeological Sciences of Bradford University. Initially under the direction of Dr. Rick Jones, and thereafter Dr. Simon Clarke, the project would employ the most modern archaeological techniques to the Trimontium site for the first time. Towards the end of the 5 year project the situation for the Trimontium site looked perilous - a new bypass was scheduled to cut through the south annexe of the fort site. The Trimiontium Trust gave evidence at two public enquiries, arguing for the historic evidence within the site to be preserved, arguing that there was too much archaeological knowledge held within the area to be disturbed. Dr Simon Clarke uncovered forty major archaeological features in his 1994 'rescue excavation', including six deep pits containing a wealth of organic material. In 1996 Dr. Clark returned to the site to examine the suspected amphitheater and suspected north annexe and in 1997 the Bradford University team completed the geophysics survey of the Trimontium site.[12]

Museums

The Trimiontium Trust run a museum local to the Trimontium site in the nearby town of Melrose. The museum is currently (as of Summer 2020) under redevelopment as part of a HLF funded project to enhance and extend the galleries, displays and interpretation of the Trimontoum story. The trust carry out guided walks to the Trimontium site, run a lecture and talk series of events, undertake activities linked to local community events and deliver school & family workshops.

Many of the original and later finds from Trimontium are of such quality and importance that they are displayed at National Museums Scotland (NMS) in Chambers Street, Edinburgh. The quantity and quality of the finds on display warrant a lengthy visit to the ground floor galleries where key items such as the cavalry helmets and decorative face mask, horse chamfron, leather work and much else besides can be seen.

The current Trimontium Trust museum redevelopment project will see key finds return to the vicinity of the original fort site & archaeological excavations. They will be housed within a contemporary museum setting as part of the trust's plans to extend, redesign, reinterpret and re-display objects telling the story of Trimontium and it's relationship with the local population.

References

- Chief. "The Fort". Trimontium Museum. Retrieved 2020-04-20.

- Mann, John C.; Breeze, David J (1987). "Ptolemy, Tacitus and the tribes of north Britain" (PDF). Proc Soc Antiq Scot. 117: 85–91.

- Chief. "Septimius Severus". Trimontium Museum. Retrieved 2020-04-20.

- "10 Facts About The Antonine Wall". History Hit. Retrieved 2020-04-20.

- "Border Archaeology - The Last Posts for Trimontium". sites.google.com. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- The Trimontium Trust (1994). The Trimontium Story. Scotland: The Trimontium Trust. p. 4.

- The Trimontium Trust (1994). The Trimontium Story. Scotland: The Trimontium Trust. p. 5.

- The Trimontium Trust (1994). The Trimontium Story. Scotland: The Trimontium Trust. p. 6.

- "Border Archaeology - The Last Posts for Trimontium". sites.google.com. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- "Border Archaeology - The Last Posts for Trimontium". sites.google.com. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- The Trimontium Trust (1994). The Trimontium Story. Scotland: The Trimontium Trust. p. 14.

- Clarke, Simon; Wise, Alicia (1999). "Evidence for extramural settlement north of the Roman fort at Newstead (Trimontium), Roxburghshire" (PDF). Proc Soc Antiq Scot. 129: 373–391.

Bibliography

Curle, J., 1911, A Roman Frontier Post and its People: The Fort of Newstead in the Parish of Melrose. Glasgow: James Maclehose and Sons.

Elliot, W., 1994, The Trimiontium Story. Selkirk: The Trimiontium Trust

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Trimontium (Newstead). |

- The Trimontium Trust Museum, Melrose

- The Newstead Project

- Curle's Newstead online

- NMS Scotland Newstead (Trimontium) objects

![]()