Moravian Serbia

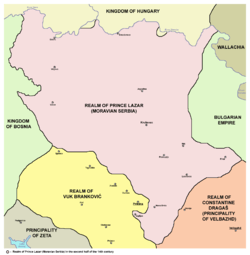

Moravian Serbia (Serbian: Моравска Србија / Moravska Srbija) or Realm of Prince Lazar is the name used in historiography for the largest and most powerful Serbian principality to emerge from the ruins of the Serbian Empire (1371).[1] Moravian Serbia is named after Morava, the main river of the region.[2] Independent principality in the region of Morava was established in 1371, and attained its largest extent in 1379 through the military and political activities of its first ruler, prince Lazar Hrebeljanović. In 1402 it was raised to the Serbian Despotate, which would exist until 1459 (de jure until the 1560s).

Moravian Serbia Моравска Србија Moravska Srbija | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1371–1402 | |||||||||

Reconstructed Flag of the former Serbian Empire

| |||||||||

Moravian Serbia | |||||||||

| Capital | Kruševac | ||||||||

| Common languages | Serbian | ||||||||

| Religion | Serbian Orthodox | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Prince (Knyaz) | |||||||||

• 1371–1389 | Lazar Hrebeljanović | ||||||||

• 1389–1402 | Stefan Lazarević | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1371 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1402 | ||||||||

| Currency | Serbian perper | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | RS | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The adjective Moravian does not imply that the state (Moravian Serbia) is affiliated in any way with the region of Moravia in the present-day Czech Republic. The term Moravian Serbia refers to the fact that the state comprised the basins of the Great Morava, West Morava, and South Morava rivers in present-day central Serbia.

History

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Serbia | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||

Lazar Hrebeljanović was born in around 1329 in the fortress of Prilepac, near the town of Novo Brdo in the region of Kosovo, Kingdom of Serbia. Lazar was a courtier at the court of Serbian Tsar Stefan Uroš Dušan, and at the court of Dušan's successor, Tsar Stefan Uroš V (r. 1356–1371).[3] Uroš's reign was characterized by the weakening of the central authority and the gradual disintegration of the Serbian Empire. Powerful Serbian nobles became practically independent in the regions they controlled.[4]

Lazar left the court Tsar Uroš in 1363 or 1365, and became a regional lord. He held the title of prince since at least 1371.[4] His territory initially developed in the shadow of stronger regional lords. The strongest were the Mrnjavčević brothers, Vukašin and Jovan Uglješa. They were defeated and killed by the Ottoman Turks in the Battle of Mariča in 1371, after which Lazar took a part of their territory. Lazar and Tvrtko I, the Ban of Bosnia, jointly defeated in 1373 another strong noble, Nikola Altomanović. Most of Altomanović's territory was acquired by Lazar. About that time, Lazar accepted the suzerainty of King Louis I of Hungary,[5] who granted him the region of Mačva, or at least a part of it. With all these territorial gains, Lazar emerged as the most powerful Serbian lord.[6] The state he then created is known in historiography as Moravian Serbia.[7]

Moravian Serbia attained its full extent in 1379, when Lazar took Braničevo and Kučevo, ousting the Hungarian vassal Radič Branković Rastislalić from these regions.[8] Lazar's state was larger than the domains of the other lords on the territory of the former Serbian Empire. It also had a better organized government and army. The state comprised the basins of the Great Morava, West Morava, and South Morava Rivers, extending from the source of South Morava northward to the Danube and Sava Rivers. Its north-western border ran along the Drina River. Besides the capital Kruševac, the state included important towns of Niš and Užice, as well as Novo Brdo and Rudnik, two richest mining centres of medieval Serbia. Of all the Serbian lands, Lazar's state lay furthest from Ottoman centres, and was least exposed to the ravages of Turkish raiding parties. This circumstance attracted immigrants from Turkish-threatened areas, who built new villages and hamlets in previously poorly inhabited and uncultivated areas of Moravian Serbia. There were also spiritual persons among the immigrants, which stimulated the revival of old ecclesiastical centres and the foundation of new ones in Lazar's state.[6][7]

A Turkish raiding party, passing unobstructed through territories of Ottoman vassals, broke into Moravian Serbia in 1381. It was routed by Lazar's nobles Crep Vukoslavić and Vitomir in the Battle of Dubravica, fought near the town of Paraćin.[7] In 1386, the Ottoman Sultan Murad I himself led much larger forces that took Niš from Lazar. It is unclear whether the encounter between the armies of Lazar and Murad at Pločnik, a site southwest of Niš, happened shortly before or after the capture of Niš. Lazar rebuffed Murad at Pločnik.[9] After the death of King Louis in 1382, a civil war broke out in the Kingdom of Hungary. Lazar briefly participated in the war as one of the opponents of Prince Sigismund of Luxemburg, and he sent some troops to fight in the regions of Belgrade and Syrmia. These fights ended with no territorial gains for Lazar, who made peace with Sigismund in 1387.[10]

In the Battle of Kosovo fought on 15 June 1389, Lazar led the army which confronted a massive invading army of the Ottoman Empire commanded by Sultan Murad I. Both Prince Lazar and Sultan Murad lost their lives in the battle. Although the battle was tactically a draw, the mutual heavy losses were devastating only for the Serbs.[7][11] Lazar was succeeded by his eldest son Stefan Lazarević. As he was still a minor, Moravian Serbia was administered by Lazar's widow, Milica. She was attacked from north, five months after the battle, by troops of the Hungarian King Sigismund. When Turkish forces, moving toward Hungary, reached the borders of Moravian Serbia in the summer of 1390, Milica accepted Ottoman suzerainty.[11]

Stefan Lazarević participated as an Ottoman vassal in the Battle of Karanovasa in 1394, the Battle of Rovine in 1395, the Battle of Nicopolis in 1396, and in the Battle of Angora in 1402. After Angora, he visited Constantinople, the capital city of the Byzantine Empire, where he was given the title of Despot, and since then his state became known as the Serbian Despotate in 1402.[12]

Rulers

- Lazar Hrebeljanović (1371–1389)

- Stefan Lazarević (1389–1402)

Notes

- Ćirković 2004, p. 79.

- Samardžić & Duškov 1993, p. 104.

- Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 15–28

- Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 29–52

- Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 53–77

- Fine 1994, p. 387-389.

- Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 116–32

- Mihaljčić 2001, pp. 78–115

- Reinert 1994, p. 177

- Fine 1994, p. 395-398.

- Fine 1994, p. 409-414.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 88.

References

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

- Ivić, Pavle, ed. (1995). The History of Serbian Culture. Edgware: Porthill Publishers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mihaljčić, Rade (2001) [1984]. Лазар Хребељановић: историја, култ, предање (in Serbian). Belgrade: Srpska školska knjiga; Knowledge. ISBN 86-83565-01-7.

- Orbini, Mauro (1601). Il Regno de gli Slavi hoggi corrottamente detti Schiavoni. Pesaro: Apresso Girolamo Concordia.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Орбин, Мавро (1968). Краљевство Словена. Београд: Српска књижевна задруга.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reinert, Stephen W (1994). "From Niš to Kosovo Polje: Reflections on Murād I's Final Years". In Zachariadou, Elizabeth (ed.). The Ottoman Emirate (1300–1389). Heraklion, Greece: Crete University Press. ISBN 978-960-7309-58-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Samardžić, Radovan; Duškov, Milan, eds. (1993). Serbs in European Civilization. Belgrade: Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sedlar, Jean W. (1994). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500. Seattle: University of Washington Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Soulis, George Christos (1984). The Serbs and Byzantium during the reign of Tsar Stephen Dušan (1331-1355) and his successors. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Library and Collection.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)