Second War of Scottish Independence

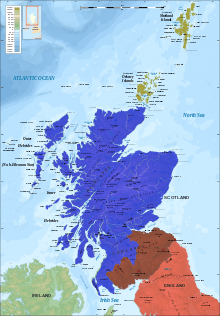

The Second War of Scottish Independence, also known as the Anglo-Scottish War of Succession[1] (1332–1357) was the second cluster of a series of military campaigns fought between the Kingdom of Scotland and the Kingdom of England in the late 13th and early 14th centuries.

The Second War arose from lingering issues from the First. The Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton by which the First War had been settled had never been popularly accepted among the English, and it had created a new group of disenfranchised nobles called the "disinherited" who felt unduly deprived by it of their rights to Scottish lands. One of these "disinherited" was Edward Balliol, son of a former Scottish king. With the discreet backing of Edward III of England, Balliol demanded the return of his ancestral lands, and when these were not forthcoming invaded Scotland, following which he had himself crowned King of Scots, despite the young David II already holding the title. What followed became both a war of succession and civil war, as some Scottish citizens rose in defense of David II and others cast their lot with Edward Balliol, who was soon joined in his efforts by the English king. David II was forced to take shelter under the "Auld Alliance" with Philip VI of France until he reached his majority, while a series of guardians including future Scottish king Robert Stewart fought back and forth battles with Balliol and Edward III for territory in Scotland. Upon his majority, he returned, but was not long in Scotland before he was captured by the English, following which he served for the rest of the Second War as a bargaining point.

The politics of the situation were ever complex. The Scottish faced discord in their own ranks, as various nobles jockeyed for position and power both before and after the majority of David II. Balliol's English allies grew distracted from his cause by their own growing preoccupation with France, with whom they were poised to enter the Hundred Years' War. The same conflict weakened the ability of the French to aid the Scots in their battles. Eventually, after several decades of repeated engagements, the Second War of Scottish Independence was settled with the signing of the Treaty of Berwick in 1357. Balliol had already relinquished his claim to the Scottish crown to Edward III, who dropped his pursuit of Scotland and released the then-captive David II in return for a pledge of 100,000 merks.

Background

The First War began when the English invaded Scotland in 1296, forcing the Scottish King John Balliol to abdicate, and ended shortly after Edward II of England was deposed and killed in 1327. Following Edward II's death, Robert the Bruce invaded Northern England and, on 1 May 1328, forced the adolescent Edward III of England to sign the Treaty of Edinburgh–Northampton which recognised the independence of Scotland with Bruce as King. To further seal the peace, Robert's very young son and heir David married Joan, the likewise youthful sister of Edward III. When Robert the Bruce died in 1329, he left his five-year-old son David heir to his throne. David II was crowned and anointed king of Scotland on 24 November 1331.[2] Until his own sudden death in 1332, Thomas Randolph, 1st Earl of Moray, would serve as regent.

But the so-called "Peace of Northampton" was to be short-lived.[3] Edward III had not acted under his own auspices, but under the pressure of his regent, Roger Mortimer, 1st Earl of March, and his mother Isabella of France.[4] Dubbed by the English "the shameful peace", the Treaty had failed to make war reparations to a group of nobles with land and position in both England and Scotland whose property and titles had been bestowed on the Bruce's allies.[5][6] With a depleted treasury and an increasingly unpopular regent controlling the throne, the outraged English people and the minor king of England were not yet in position to attempt to do anything about it.[4] But the year following the coronation of David II, 1330, two significant events occurred: Edward III had his regent executed, taking control of his crown and country,[7] and Edward Balliol made an appeal to the English king.[2]

Edward Balliol was the eldest son of John Balliol, who had been forced to abdicate the Scottish throne following the invasion of 1296, and Isabella de Warenne, daughter of John de Warenne, 6th Earl of Surrey and Alice of Lusignan. An important figurehead and chief among the disinherited, Edward Balliol wanted the return of certain ancestral lands, and at the end of the year Edward III conveyed his demands to David II's regent, Thomas Randolph.[2] When Thomas Randolph delayed response, Edward III pressed the matter, repeating the request on 22 April 1332. And though Edward III did not openly give his support, Balliol and his followers began preparing for invasion of Scotland.[8]

The repelled invasion of Edward Balliol – 1332

The first skirmish of the Second War of Scottish Independence took place in August 1332, when Edward Balliol and his Disinherited followers took the day at the Battle of Dupplin Moor.[9] The decisive victory left the invaders well placed in Scotland, where their ranks swelled as those who had not supported the Bruce cast their lots. Particularly prominent among Balliol's supporters were residents of Fife and Strathearn.[10] On 24 September, Edward Balliol was crowned the King of Scots, under which title he continued to rally supporters and to march across the country, settling in Roxburgh.[11] There, on 23 November, Edward Balliol offered his loyalty to Edward III as his liege, offering also to wed David II's sister and to give Edward III substantial lands in Scotland.[12] He also pledged his support to Edward III's future battles on penalty of all of Scotland and its isles. Afterward, he withdrew to Annan, but did not long remain there before he was driven from Scotland in a battle led by Sir Archibald Douglas and John Randolph, 3rd Earl of Moray.[13][14]

David II's resistance had been hampered even before the first skirmish by the unexpected illness and death of his Guardian.[13] Thomas Randolph was briefly replaced by Domhnall II, Earl of Mar, but the new Guardian died days after his appointment in the Battle of Dupplin Moor, and another Guardian had to be quickly located. Sir Andrew Murray was appointed to the position and took off in pursuit of Edward Balliol, but Murray was taken prisoner and had to himself be replaced. The next to be chosen Guardian was the military leader who had succeeded in rousting Edward Balliol, Archibald Douglas.

Edward III invades: 1333 – 1334

Cassell's History of England – Century Edition

After being rousted from Annan, Edward Balliol again offered homage to Edward III, and though the idea of returning to war against Scotland did not have universal appeal, Edward III gave Balliol his backing.[13] The English king claimed that the violation of the Treaty of Northampton was not his own, but those Scots who crossed the borders after Edward Balliol's ouster.[12] Balliol returned to Scotland in March 1333, besieging Berwick-upon-Tweed. In response, Archibald Douglas counterattacked, which Edward III took as excuse to justify open battle.[13] He traveled to Northumberland in May, where he and the pretender to the Scottish throne began preparing for battle, while elsewhere Archibald Douglas did the same. There was particular urgency to Scottish preparations, for Berwick had agreed to surrender to the English if it were not liberated by 20 July.[15]

On 19 July 1333, Sir Archibald Douglas and his men came to face the troops of Balliol and Edward III at the Battle of Halidon Hill, just to the north-west of Berwick.[13] Though greater in number, the Scottish forces were severely hampered by the lay of the land. Their cavalry was forced to dismount by boggy earth and proceed on foot uphill against English archers, who picked them off in great number.[13][16] Once weakened, they were overrun by the English cavalry, who claimed among their many victims Sir Archibald Douglas himself. The loss of the Guardian was a severe blow for loyalists to David II, who would soon be carried into exile in France, there to remain until 1341.[17]

Quite quickly, Edward Balliol made formal his promises to Edward III. Andrew Lang records that in a Parliament held in February 1334, Balliol "acknowledged fealty and subjection to his English namesake, and surrendered Berwick as an inalienable possession of the English crown", following which in July the same year Balliol yielded considerably more to Edward III, including Roxburgh, Edinburgh, Peebles, Dumfries, Linlithgow, and Haddington.[18] Edward III did not displace the Scottish laws governing his new territories, but he put his own men in charge of his new territories.

New unrest among the Scots

But while David II was safely removed and Edward III attending to other things, Edward Balliol was troubled not only by unrest among Scottish nationalists but also by discord among his own allies.[19] The common goal attained, his allies began to look to their own self interests, which did not always accord with each other's or Balliol's own. His three primary allies had been Richard Talbot, Henry de Beaumont and David III Strathbogie.[20] When Alexander de Mowbray petitioned Balliol for the lands of his brother, who had died with only daughters, these three stood for the daughters and, when Balliol granted the petition, withdrew severally to take matters into their own hands.[21]

At the same time that Balliol's allies were leaving him, his enemies seemed to be gathering strength. Scottish ships of war waited off the coast to disrupt supplies sent by Edward III, and the captive Sir Andrew Murray, formerly Guardian of David II, was released to return home. Balliol attempted to placate his three primary allies by withdrawing his support of de Mowbray, but only succeeded in convincing de Mowbray to throw in with the son of the Bruce.[22]

Balliol's allies, divided, proved easier targets. Talbot was taken by loyalist William Keith of Galston and imprisoned in Dumbarton Castle, where once David II had taken shelter. Murray and de Mowbray pursued Beaumont, besieging him in Dundarg Castle and forcing him to retire to England.[22] Balliol had given Strathbogie the lands of Robert Stewart, one day to be king but at that time the deposed High Steward of Scotland though only an adolescent.[19] Heir to the throne currently claimed by David II, Stewart joined together with Sir Andrew Murray as co-Regents.[23] Stewart rallied support to attack Strathbogie, driving him to Lochaber where in evident "fear of his life" he decided to surrender and support the loyalists.[19]

Balliol, for his part, retreated to Berwick. There, though he managed to convince Edward III to spend the winter of 1334–1335 in Roxburgh, he could not convince his men to stop defecting to join those loyal to David II.[24] And though Balliol and the English king both led excursions into the surrounding western lowlands, destroying the property of friend and foe alike, they found no evidence of Scottish troops.[25]

The entry of France to the conflict: 1334/35

Jean Froissart, 15th century

Relations between France and England were already tense, with the English in control of the fief of Gascony and both sides struggling to impose their own interpretations of what precisely their relationship was. It had only been a few years, since 1331, that Philip VI and Edward III had begun to settle, after Edward had paid proper homage to Philip.[26]

While offering shelter to David II, Philip VI of France was also offering a clear message that, in the words of Spaltro and Bridge, "no Anglo-French peace settlement could scant the interest of France's ally Scotland."[17] France and Scotland had been joined in an "Auld Alliance" since Edward Balliol's father John had signed a treaty with Philip IV of France against Edward I of England in 1295, pledging mutual defence.

David II's new co-regents sent a plea for help to Philip VI, who in November 1334 advised Edward III that he was sending an ambassador to England to discuss the matter.[25] Accordingly, when Edward III returned from Roxburgh in February 1335, it was to find the Bishop of Avranches waiting, demanding to know why Edward III was acting against David II and David's queen, Edward's own sister Joan. Edward III deferred his answer, but in the meantime agreed to allow the ambassadors to try to negotiate peace between England and Scotland. As serious as the French ambassadors may have been at their task, they were unable to make headway with the co-regents of David II, who were at this time divided by their own disagreements about governance.[27] What they did do, unwitting as they may have been, was allow time for the English to restore their finances.[28]

The return of Edward III: 1335

In March 1335, Edward III began seriously mustering his forces, timing his invasion to the expiration of the French-engineered temporary truce.[27] Aware of his plans, Scottish loyalists were also preparing for war, setting aside their personal differences and evacuating the lowlands in preparation for invasion. Edward III summoned an army of 13,000 men, the largest assemblage he had ever managed for an invasion of Scotland, and set off in July with a plan for a three-front invasion.[29] With a naval force waiting near the Clyde, Edward III would lead part of this troop north from Carlisle while Balliol would take the rest west from Berwick. They encountered little resistance. After the armies met up at Glasgow, Edward III settled in the area of Perth.

In France, lacking an answer to his question or satisfactory settlement of his truce, Philip VI openly assembled an army of 6,000 soldiers to send to support the Scottish troops, to whom he had also been sending supplies since February of that year.[30] Notice was sent to Edward III, informing him that if he did not submit the dispute to the arbitration of France and the Pope, the French soldiers would be deployed. Edward III flatly refused the demand.

Meanwhile, the situation among the Scottish loyalists had worsened, but only temporarily. England was regaining ground, and both Strathbogie and Robert Stewart surrendered to Edward III,[23] Strathbogie so enthusiastically that he was later known for his tyranny against the loyalists.[31] The remaining loyalists gathered at Dumbarton Castle, with the sole remaining regent, Sir Andrew Murray.[23] To discuss terms, Murray and Edward III established a truce, which ultimately lasted from mid-October through Christmas, but the truce did not govern Balliol or Balliol's followers.[32] When Strathbogie lay siege against Murray's wife at Kildrummy Castle, Murray went after him, and with the assistance of the recently ransomed William Douglas, Lord of Liddesdale, killed Strathbogie and routed Strathbogie's troops at the Battle of Culblean.[32] It was the first of a number of victories against Balliol and his followers that gradually pushed Balliol to shelter in the shadow of the English king.[33]

Edward III seems at this point to have been primarily interested in maintaining the eight counties which Balliol had given him, which he was restoring to military strength.[33] In spite of his flat refusal to meet Philip VI's demands, he was concerned about the potential actions of the French, particularly against his inherited lands in that country.[34] Through the winter, the treaty remained under discussion, promoting the idea that the middle-aged Edward Balliol might retain the throne and David II — who would relocate to England — be named his heir.[31][35] Philip VI, David II's protector and adviser, had been persuaded by Pope Benedict XII to postpone his own military action,[35] but in March 1336 he persuaded David II to reject the treaty, which evidently his regent had been prepared to accept.[31][36] There were just weeks to go in the treaty, following which Edward III intended to press on with the war.

In May 1336, Edward III sent Henry of Lancaster to enter Scotland, where the Scottish leaders were involved in sieges at Lochindorb and Cupar.[37] Lancaster paused for reinforcements at Perth, sending Sir Thomas Rosslyn ahead to fortify the ruined castle of Dunnottar. Edward III was receiving grave and probably inflated intelligence of the amassing forces of Philip VI, which were intending to land in Scotland and invade England from the north, and he determined to thwart the plan by eliminating the most likely port for their arrival: Aberdeen.[38]

In June, Edward III arrived in Scotland via Newcastle with a force of 400 men, picking up an additional 400 from Lancaster's troops with which to march on Lochindorb, ending that siege, and thence to the Moray Firth.[39] He destroyed everything he encountered from there through Aberdeen, which he burned to the ground. Later that same month, Carrick Clydesdale were likewise devastated by an attack of several thousand men under the command of John of Eltham, Earl of Cornwall.[40]

France joins the fight: 1336

Meanwhile, an English embassy empowered by the Great Council of June 1336 had been attempting to negotiate with Philip VI and David II. In August, Philip VI gave the English ambassadors his final answer, that he intended to invade England and Scotland immediately with the fleet and army he had gathered.[41] The ambassadors sent urgent word to the Council of England, but two days before the messenger's arrival, on 22 August, four French privateers attacked the English town of Orford. Soon after the messenger arrived and was dispatched to call Edward back to England, French privateers captured several royal ships and loaded merchantmen anchored at the Isle of Wight.[42]

It was the middle of September before Edward III received that word and returned to England, abandoning his immediate plans to attack Douglas of Liddesdale in light of the greater threat. Too late to strike at the French ships, Edward III aggressively raised funds and returned to Scotland, beginning a series of wins and losses of castles before settling to winter at the fortress in Clyde.[43] Douglas of Liddesdale kept up a campaign of harassment against the king, while Murray destroyed Dunnottar, Kinneff and Lauriston in order to prevent Edward III using them to his own advantage.[44] Famine and disease exacted harsh tolls throughout Scotland. In England, though French naval attacks were dying down, French political and legal pressures were increasing. Edward III again returned to England in December 1336 and began to plan a force to enter Gascony in the spring.[45]

Scottish resurgence: 1336 – 1340

The Scottish loyalists pressed the advantage of Edward III's distraction. Murray and Douglas of Liddesdale made incursions into the English strongholds of Perth and Fife and met no real resistance.[46] Shortly thereafter, they negotiated terms with the troops garrisoned at Bothwell Castle, immediately afterward destroying the English fortifications. This was only the start. By the end of March, the Scottish troops had reclaimed most of Scotland north of the Forth and done serious damage to the lands of Edward Balliol.

Edward III continued to focus on France, though he made clear his intentions of addressing Scotland when time permitted.[47] But at the same time that Edward III was considering how best to deal with the French, the French were continuing to pour supplies into Scotland, and as the year progressed the Scottish forces began to encroach even into northern England, laying waste to Cumberland.[48] Such actions forced Edward III to take the Scottish threat seriously, and in October he sent William Montagu, 1st Earl of Salisbury, to Scotland to see what he could do to contain the situation.

Salisbury proved able to do little. He took his forces to Dunbar, launching an attack in January 1338 against its Countess, "Black Agnes" Randolph, the daughter of the former regent Thomas Randolph and the wife of one Patrick de Dunbar, 9th Earl of March.[49] With the aid of Alexander Ramsay of Dalhousie, she withstood, and Salisbury withdrew on Edward III's command after six months of effort in June. Salisbury would, however, feature in the Second War again in 1341 when, as a prisoner of the French, his return to the English would be a bargaining point for the release of the Scottish John Randolph.

While not to say that Scottish victory was imminently on the horizon, the early winter and spring of 1338 were a turning point for the Scottish campaign.[50] Murray in particular was ruthless, and while suffering his own defeats left such destruction in his wake that thousands of Scottish civilians were left without food to sustain themselves, much less to fuel Balliol's cause. However, it was his dying blow. Early in the year, Murray died of an illness, but not before he had, in the words of Michael Brown, "ended the possibility of Edward III establishing stable lordship over southern Scotland."[50]

Meanwhile, William Douglas had settled in the area of Liddesdale, from which position he harassed the allies of the English.[50] In Spring 1339, Stewart — sole Guardian after Murray's death — brought a large force against the shrinking region under Balliol's control around Perth and Cupar. English reinforcements were held back by Scottish and French ships, and Stewart won the day in August, when his enemies surrendered.

David II leading Scotland: 1341 – 1346

Jean Froissart

In 1341, David II reached the age of 18. He returned to Scotland on 2 June of that year with his wife, Edward III's sister, Joan.[51] While the battles with the English had cooled in recent years, infighting amongst the Scottish loyalists had once again become an issue, and David II was eager to establish his own authority and surround himself with his own people.[51][52] These urges caused David II to make some questionable decisions that probably had the opposite effect of what he had intended. David knew that Douglas had an interest in Liddesdale, but he bestowed it instead on Stewart in 1342. Stewart — more interested in Atholl, which had already been bestowed on Douglas — was willing to swap, an act which not only increased the powers of Douglas and Stewart but also suggested little respect for David II's authority.[53] Perhaps in response, David II rewarded Alexander Ramsay of Dalhousie for retaking Roxburgh Castle from the English by appointing him sheriff. This act enraged Douglas, who had tried to retake Roxburgh himself several times and who had by some reports already been given the position.[51] He imprisoned Ramsay and took brutal revenge, starving him to death in Hermitage Castle. Although himself dismayed by the death of Ramsay,[54] Stewart intervened between Douglas of Liddesdale and the king, and Douglas was pardoned.[55]

Fighting with the English also continued. David II conducted several raids into England,[51] as did John Randolph.[55] In February 1343, the French and English entered into a treaty that also involved Scotland. While this was meant to last until 29 September 1346, several skirmishes in the intervening years did disturb the peace. But it was not until late in 1346, when Philip VI appealed to his ally David II for support, that circumstances would undergo a major change.[54]

Having sustained serious losses at the Battle of Crécy in August and fearing further losses in an English invasion, Philip VI asked David II to himself invade England.[51] Notwithstanding rivalries and divisions within his own troops, David summoned a massive army to Perth in September 1346.[54] But David II's approach was indirect, and the English had time to muster forces of their own. These armies engaged in the Battle of Neville's Cross on 17 October 1346, near Durham.

For the Scottish forces, it proved a disaster. The battle had already begun to go poorly for the Scots when Robert Stewart and Patrick de Dunbar withdrew with their rearguard, leaving the rest of the troops to defeat. By the time the battle was over, John Randolph was among the slain and William Douglas of Liddesdale among the captives. David II as well, was captured, taken wounded from the field.[51]

The captivity of David II: 1346 – 1357

David II would remain captive to the English until 1357, during much of which time he resided in the Tower of London.[51] Among the combatants at Neville's Cross, Edward Balliol set about recruiting forces to join him on an excursion back into Scotland, while Henry Percy and John Neville swiftly pressed the English advantage in the borders.[56] But though Balliol's subsequent campaign did restore some of the Southern communities to Edward III, on the whole he made little headway. Edward III was far more interested in the situation in France, and the Scottish locals were far less willing to submit to Balliol's demands.

In the absence of the king, the Scottish forces rallied again behind Robert Stewart, supported by de Dunbar and Uilleam Ross, among others. Stewart could be depended upon to defend Scotland from Edward III and Edward Balliol, but otherwise was more interested in securing his own power than looking after that of his king.[57] As Stewart looked after himself, voids left by Neville's Cross were being filled as well in other parts of Scotland. Notably, to fill the gap left by William Douglas, Lord of Liddesdale, came his namesake and ward, the son of Sir Archibald Douglas, to assume the lordship of Douglas, from which position he became a powerful leader for the Scottish in the war.[57][58]

With David II in his custody, Edward III had a good opportunity to try to reach terms, though Edward Balliol's interests were a sticking point.[59] He had evidently prepared to overlook them by the time he made his first offer, in 1348, which seems to have been that David II would hold Scotland as a fief for England, naming Edward III or one of his sons as his successor, should he die without children.[51] This had altered somewhat by 1350 when Edward III sent Douglas of Liddesdale, also in custody in the Tower of London, to see if the Scots would be willing to take different terms: to ransom David II for a fee of £40,000, the restoration of the disinherited lords, and the naming of Edward III's young son John of Gaunt as David's successor, should he die without children.[60][61] David himself is credited with removing Edward III's name from the line of succession in Scotland,[51] and the Scots seem to have been willing to entertain the idea as they sent Douglas of Liddesdale back for further negotiation and David II was himself permitted to briefly return to Scotland in early 1352 to try to seal the deal.[51][60] Stewart would obviously be disinclined to support terms that removed him from succession, but he seems ultimately not to have been alone.[61] The Parliament convened in March 1352 did not find the prospect of submitting to the English a fair trade for the freedom of their king. David II was sent back.

Still preoccupied with the war in France, Edward III tried again in 1354 with a simple demand of ransom, without settlement of the claim of England to superiority, but the Scots rejected this as well, perhaps because Robert Stewart was contemplating instead a stronger alliance with France.[51] It was with French backing around 1355 that the Scottish forces began again to escalate against England.[62] They launched a successful assault against Berwick, which fell under Scottish control.

Edward III reacted swiftly. In early 1356, along with Edward Balliol, he invaded Scotland, leading to an episode that would become known as the Burnt Candlemas. After recapturing Berwick and overwintering at Roxburgh, he spent ten days at Haddington, where he sacked the town and destroyed most of the buildings. His army ravaged the whole of Lothian, burning Edinburgh and the Shrine of the Virgin at Whitekirk.[62][63]

Treaty of Berwick (1357)

The episode demonstrated to both Scotland and England the fruitlessness of their struggles.[62] Thereafter, with France's fortunes falling and England's rising, the terms came to seem more favourable to the Scots, and in 1357 they were accepted after all, formalized in the Treaty of Berwick, under the terms of which Scotland would pay England 100,000 merks over a ten-year period.[51]

With the signing of the Treaty of Berwick, the Second War of Scottish Independence was effectively over. Even before the signing of the treaty, in January 1356, Edward Balliol — weary and ill — had relinquished his claim in the kingdom of Scotland to Edward III in exchange for an annuity of £2000.[59][62] He retired to live the rest of his life in the area of Yorkshire. David II returned to Scotland, to try again to deal with the rivalries of his lords as well as now among his ladies, as his wife Joan evidently objected to the English mistress he had taken during his 11 years in captivity.[51] The treaty did impose a financial hardship on Scotland, but David II stopped paying after only 20,000 merks of the debt had been met, following which renegotiation led ultimately to a reduction in the debt and a 14-year truce.

Notes

- Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: F-O. Santa Barbara: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 530. ISBN 9780313335389. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- Lang, 243.

- Creighton, 219.

- Weir, 314.

- Weir, 313–314.

- In 2002, Cameron and Ross challenge the widely held assumption that no provisions for restorations were made in the Treaty, but suggest that instead a clause that did make such provisions was not honoured. Cameron, Sonja; Alasdair Ross (16 December 2002). "The Treaty of Edinburgh and the Disinherited (1328–1332)". History. 84 (274): 237–256. doi:10.1111/1468-229X.00107. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012.

- Creighton, 229.

- Brown, 232.

- Liddy, 59.

- Brown, 234.

- Brown, 234–235.

- Lang, 246.

- Brown, 235.

- Boardman (2004).

- Conduit, 27.

- Conduit, 28.

- Spaltro and Bridge, 69.

- Lang, 249-50.

- Lang, 250.

- Tytler, 410.

- Tytler, 410–411.

- Tytler, 411.

- Sumption, 148.

- Brown, 238.

- Sumption, 142.

- Rogers, 241.

- Sumption, 143.

- Sumption, 142-43.

- Sumpton, 144.

- Sumption, 145–146.

- Brown, 239

- Sumption, 149.

- Sumption, 150.

- Sumption, 150–151.

- Sumption, 153.

- Sumption, 154.

- Sumption, 158.

- Sumption, 159–161.

- Sumption, 161.

- Sumption, 162.

- Sumption, 163.

- Sumption, 164.

- Sumption, 166.

- Sumption, 166–167.

- Sumption, 173.

- Sumption, 179.

- Sumption, 180.

- Sumption, 214.

- Lang, 254.

- Brown, 241.

- Webster, "David II" (2004).

- Brown, 244–245.

- Brown, 245.

- Brown, 247.

- Lang, 256.

- Brown, 248.

- Brown, 249.

- Lang, 258.

- Webster "Balliol, Edward" (2004)

- Duncan (2004)

- Brown, 251.

- Brown, 253.

- Major et al., 296–297.

References

- Boardman, S.I. (2004). "Randolph, John, third earl of Moray (d. 1346)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23119. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- Brown, Michael (28 July 2004). The wars of Scotland, 1214-1371. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1238-3. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- Creighton, Mandell (1886). Epochs of English history: A complete edition in one volume. Longmans, Green & co. p. 219. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- Conduit, Brian (25 September 2005). Battlefield Walks in Northumbria and Scottish Borders. Sigma. ISBN 978-1-85058-825-2. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- Duncan, A.A.M. (2004). "Douglas, Sir William, lord of Liddesdale (c. 1310–1353)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/7923. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- Fry, Plantagenet Somerset (1 April 2007). Castles: Scotland & the Border Country: The Essential Visitor Guide to the Best of the Region. David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-2707-4. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- Lang, Andrew (1903). A history of Scotland from the Roman occupation. Dodd, Mead and Co. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- Liddy, Christian Drummond; R. H. Britnell (2005). North-east England in the later Middle Ages. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-127-3. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- Major, John; Archibald David Constable; Aeneas James George Mackay; Thomas Graves Law (1892). A history of Greater Britain as well England as Scotland. Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society. p. 297. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- Rogers, Clifford J. (1999). The wars of Edward III: sources and interpretations. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85115-646-0. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- Spaltro, Kathleen; Noeline Bridge (December 2005). Royals of England: A Guide for Readers, Travelers, and Genealogists. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-37312-3. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- Sumption, Jonathan (1999). The Hundred Years War: Trial by battle. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1655-4. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- Tytler, Patrick Fraser (1845). History of Scotland. W. Tait. p. 14. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- Webster, Bruce (2004). "Balliol, Edward (b. in or after 1281, d. 1364)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/1206. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- Webster, Bruce (2004). "David II (1324–1371)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/3726. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- Weir, Alison (26 December 2006). Queen Isabella: Treachery, Adultery, and Murder in Medieval England. Random House, Inc. p. 314. ISBN 978-0-345-45320-4. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

Further reading (primary sources)

- Anonimalle Chronicle, 1333-81, ed. V. H. Galbraith, 1927.

- Bower, Walter, Scotichronicon, ed. D. E. R. Watt, 1987-96.

- Brut, or the Chronicles of England, ed. F. W. D. Brie, 1906.

- Capgrave, John, The Book of the Illustrious Henries, ed. F. Hingeston, 1858.

- Calendar of Documents Relating to Scotland, ed. J. Bain, 1857.

- Fordun, John, Chronicles of the Scottish Nation, ed. W. F. Skene, 1872.

- Gray, Thomas, Scalicronica, ed. H. Maxwell, 1913.

- The Lanercost Chronicle, ed. H. Maxwell, 1913.

- Wyntoun, Andrew, The Original Chronicle of Scotland, ed. F. J. Amours, 1907.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wars of Scottish Independence. |