Grammar school

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented secondary school, differentiated in recent years from less academic secondary modern schools. The main difference is that a grammar school may select pupils based on academic achievement whereas a secondary modern may not.

.jpg)

The original purpose of medieval grammar schools was the teaching of Latin. Over time the curriculum was broadened, first to include Ancient Greek, and later English and other European languages, natural sciences, mathematics, history, geography, and other subjects. In the late Victorian era grammar schools were reorganised to provide secondary education throughout England and Wales; Scotland had developed a different system. Grammar schools of these types were also established in British territories overseas, where they have evolved in different ways.

Grammar schools became the selective tier of the Tripartite System of state-funded secondary education operating in England and Wales from the mid-1940s to the late 1960s and continuing in Northern Ireland. With the move to non-selective comprehensive schools in the 1960s and 1970s, some grammar schools became fully independent schools and charged fees, while most others were abolished or became comprehensive (or sometimes merged with a secondary modern to form a new comprehensive school). In both cases, many of these schools kept "grammar school" in their names. More recently, a number of state grammar schools still retaining their selective intake gained academy status, meaning that they are independent of the Local Education Authority (LEA). Some parts of England retain forms of the Tripartite System, and a few grammar schools survive in otherwise comprehensive areas. Some of the remaining grammar schools can trace their histories to before the 16th century.

History

Medieval grammar schools

Although the term scolae grammaticales was not widely used until the 14th century, the earliest such schools appeared from the sixth century, e.g. the King's School, Canterbury (founded 597) and the King's School, Rochester (604).[1][2] The schools were attached to cathedrals and monasteries, teaching Latin – the language of the church – to future priests and monks. Other subjects required for religious work were occasionally added, including music and verse (for liturgy), astronomy and mathematics (for the church calendar) and law (for administration).[3]

With the foundation of the ancient universities from the late 12th century, grammar schools became the entry point to a liberal arts education, with Latin seen as the foundation of the trivium. Pupils were usually educated in grammar schools up to the age of 14, after which they would look to universities and the church for further study. Three of the first schools independent of the church – Winchester College (1382), Oswestry School (1407) and Eton College (1440) – were closely tied to the universities; they were boarding schools, so they could educate pupils from anywhere in the nation.[3][4]

Early Modern grammar schools

An example of an early grammar school, founded by an early modern borough corporation unconnected with church, or university, is Bridgnorth Grammar School, founded in 1503 by Bridgnorth Borough Corporation.[5]

During the English Reformation in the 16th century, most cathedral schools were closed and replaced by new foundations funded from the dissolution of the monasteries.[3] For example, the oldest extant schools in Wales – Christ College, Brecon (founded 1541) and the Friars School, Bangor (1557) – were established on the sites of former Dominican monasteries. King Edward VI made an important contribution to grammar schools, founding a series of schools during his reign (see King Edward's School). A few grammar schools were also established in the name of Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth I. King James I founded a series of "Royal Schools" in Ulster, beginning with The Royal School, Armagh. In theory these schools were open to all and offered free tuition to those who could not pay fees; however, few poor children attended school, because their labour was economically valuable to their families.

In the Scottish Reformation schools such as the Choir School of Glasgow Cathedral (founded 1124) and the Grammar School of the Church of Edinburgh (1128) passed from church control to burgh councils, and the burghs also founded new schools.

With the increased emphasis on studying the scriptures after the Reformation, many schools added Greek and, in a few cases, Hebrew. The teaching of these languages was hampered by a shortage of non-Latin type and of teachers fluent in the languages.

During the 16th and 17th centuries the setting-up of grammar schools became a common act of charity by nobles, wealthy merchants and guilds; for example The Crypt School, Gloucester, founded by John and Joan Cook in 1539, Spalding Grammar School, founded by John Gamlyn and John Blanche in 1588, and Blundell's School, founded in 1604 by wealthy Tiverton merchant Peter Blundell. Many of these are still commemorated in annual "Founder's Day" services and ceremonies at surviving schools. The usual pattern was to create an endowment to pay the wages of a master to instruct local boys in Latin and sometimes Greek without charge.[6]

The school day typically ran from 6 a.m. to 5 p.m., with a two-hour break for lunch; in winter, school started at 7 a.m. and ended at 4 p.m. Most of the day was spent in the rote learning of Latin. To encourage fluency, some schoolmasters recommended punishing any pupil who spoke in English. The younger boys learned the parts of speech and Latin words in the first year, learned to construct Latin sentences in the second year, and began translating English-Latin and Latin-English passages in the third year. By the end of their studies at age 14, they would be quite familiar with the great Latin authors, and with Latin drama and rhetoric.[7] Other skills, such as arithmetic and handwriting, were taught in odd moments or by travelling specialist teachers such as scriveners.

Grammar schools in the 18th and 19th centuries

In 1755 Samuel Johnson's Dictionary defined a grammar school as a school in which the learned languages are grammatically taught;[8] However, by this time demand for these languages had fallen greatly. A new commercial class required modern languages and commercial subjects.[6] Most grammar schools founded in the 18th century also taught arithmetic and English.[9] In Scotland, the burgh councils updated the curricula of their schools so that Scotland no longer has grammar schools in any of the senses discussed here, though some, such as Aberdeen Grammar School, retain the name.[10]

In England, urban middle-class pressure for a commercial curriculum was often supported by the school's trustees (who would charge the new students fees), but resisted by the schoolmaster, supported by the terms of the original endowment. Very few schools were able to obtain special acts of Parliament to change their statutes; examples are the Macclesfield Grammar School Act 1774 and the Bolton Grammar School Act 1788.[6] Such a dispute between the trustees and master of Leeds Grammar School led to a celebrated case in the Court of Chancery. After 10 years, Lord Eldon, then Lord Chancellor, ruled in 1805, "There is no authority for thus changing the nature of the Charity, and filling a School intended for the purpose of teaching Greek and Latin with Scholars learning the German and French languages, mathematics, and anything except Greek and Latin."[11] Although he offered a compromise by which some subjects might be added to a classical core, the ruling set a restrictive precedent for grammar schools across England; they seemed to be in terminal decline.[3][9] However it should be borne in mind that the decline of the grammar schools in England and Wales was not uniform and that until the foundation of St Bees Clerical College, in 1817, and St David's College Lampeter, in 1828, specialist grammar schools in the north-west of England and South Wales were in effect providing tertiary education to men in their late teens and early twenties, which enabled them to be ordained as Anglican clergymen without going to university.[12]

Victorian-era grammar schools

The 19th century saw a series of reforms to grammar schools, culminating in the Endowed Schools Act 1869. Grammar schools were reinvented as academically oriented secondary schools following literary or scientific curricula, while often retaining classical subjects.

The Grammar Schools Act 1840 made it lawful to apply the income of grammar schools to purposes other than the teaching of classical languages, but change still required the consent of the schoolmaster. At the same time, the national schools were reorganising themselves along the lines of Thomas Arnold's reforms at Rugby School, and the spread of the railways led to new boarding schools teaching a broader curriculum, such as Marlborough College (1843). The first girls' schools targeted at university entrance were North London Collegiate School (1850) and Cheltenham Ladies' College (from the appointment of Dorothea Beale in 1858).[6][9]

Modelled on the Clarendon Commission, which led to the Public Schools Act 1868 which restructured the trusts of nine leading schools (including Eton College, Harrow School and Shrewsbury School), the Taunton Commission was appointed to examine the remaining 782 endowed grammar schools. The commission reported that the distribution of schools did not match the current population, and that provision varied greatly in quality, with provision for girls being particularly limited.[6][9] The commission proposed the creation of a national system of secondary education by restructuring the endowments of these schools for modern purposes. The result was the Endowed Schools Act 1869, which created the Endowed Schools Commission with extensive powers over endowments of individual schools. It was said that the commission "could turn a boys' school in Northumberland into a girls' school in Cornwall". Across England and Wales schools endowed to offer free classical instruction to boys were remodelled as fee-paying schools (with a few competitive scholarships) teaching broad curricula to boys or girls.[6][9][13]

In the Victorian era there was a great emphasis on the importance of self-improvement, and parents keen for their children to receive a decent education organised the creation of new schools with modern curricula, though often retaining a classical core. These newer schools tended to emulate the great public schools, copying their curriculum, ethos and ambitions, and often took the title "grammar school" for historical reasons. A girls' grammar school established in a town with an older boys' grammar school would often be named a "high school".

Under the Education (Administrative Provisions) Act 1907 all grant-aided secondary schools were required to provide at least 25 percent of their places as free scholarships for students from public elementary schools. Grammar schools thus emerged as one part of the highly varied education system of England and Wales before 1944.[3][9]

In the Tripartite System

The 1944 Education Act created the first nationwide system of state-funded secondary education in England and Wales, echoed by the Education (Northern Ireland) Act 1947. One of the three types of school forming the Tripartite System was called the grammar school, which sought to spread the academic ethos of the existing grammar schools. Grammar schools were intended to teach an academic curriculum to the most intellectually able 25 percent of the school population as selected by the 11-plus examination.

Two types of grammar schools existed under the system:[14][15]

- There were more than 1,200 maintained grammar schools, which were fully state-funded. Though some were quite old, most were either newly created or built since the Victorian period, seeking to replicate the studious, aspirational atmosphere found in the older grammar schools.

- There were also 179 direct-grant grammar schools, which took between one quarter and one-half of their pupils from the state system, and the rest from fee-paying parents. They also exercised far greater freedom from local authorities, and were members of the Headmasters' Conference. These schools included some very old schools encouraged to participate in the Tripartite System. The most famous example of a direct-grant grammar was Manchester Grammar School, whose headmaster, Lord James of Rusholme, was one of the most outspoken advocates of the Tripartite System.[16]

Grammar school pupils were given the best opportunities of any schoolchildren in the state system. Initially, they studied for the School Certificate and Higher School Certificate, replaced in 1951 by General Certificate of Education examinations at O-level (Ordinary level) and A-level (Advanced level). In contrast, very few students at secondary modern schools took public examinations until the introduction of the less academic and less prestigious Certificate of Secondary Education (known as the CSE) in the 1960s.[17] Until the implementation of the Robbins Report in the 1960s, children from public and grammar schools effectively monopolised access to universities. These schools were also the only ones that offered an extra term of school to prepare pupils for the competitive entrance exams for Oxford and Cambridge.

According to Anthony Sampson, in his book Anatomy of Britain (1965), there were structural problems within the testing process that underpinned the eleven plus which meant it tended to result in secondary modern schools being overwhelmingly dominated by the children of poor and working-class parents, while grammar schools were dominated by the children of wealthier middle-class parents.[18]

The Tripartite System was largely abolished in England and Wales between 1965, with the issue of Circular 10/65, and the Education Act 1976. Most maintained grammar schools were amalgamated with a number of other local schools, to form neighbourhood comprehensive schools, though a few were closed. This process proceeded quickly in Wales, with the closure of such schools as Cowbridge Grammar School. In England, implementation was less even, with some counties and individual schools successfully resisting conversion or closure.[19][20]

The Direct Grant Grammar Schools (Cessation of Grant) Regulations 1975 required direct grant schools to decide whether to convert into comprehensives under local authority control or become independent schools funded entirely by fees. Of the direct grant schools remaining at that time, 51 became comprehensive, 119 opted for independence, and five were "not accepted for the maintained system and expected to become independent schools or to close".[21] Some of these schools retained the name "grammar" in their title but are no longer free of charge for all but a few pupils. These schools normally select their pupils by an entrance examination and sometimes by interview.

By the end of the 1980s, all of the grammar schools in Wales and most of those in England had closed or converted. Selection also disappeared from state-funded schools in Scotland in the same period. While many former grammar schools ceased to be selective, many of these also retained the name "grammar". Most of these schools remain comprehensive, though a few became partially selective or fully selective in the 1990s. The tripartite system of grammar and secondary modern schools does survive in a few areas, such as Kent, where the eleven-plus examination to divide children into grammar and secondary modern schools is known as the Kent Test.

Current British grammar schools

Today, "grammar school" commonly refers to one of the 163 remaining fully selective state-funded schools in England and the 69 remaining in Northern Ireland.

The National Grammar Schools Association campaigns in favour of such schools,[22] while Comprehensive Future and the Campaign for State Education campaign against them.[23][24]

A University College London study has shown that UK grammar school pupils gain no significant social or emotional advantages by the age of 14 over similarly gifted pupils in non-selective schools.[25]

England

At the 1995 Labour Party conference, David Blunkett, then education spokesman, promised that there would be no selection under a Labour government. However the party's manifesto for the 1997 election promised that "Any changes in the admissions policies of grammar schools will be decided by local parents."[26] Under the Labour government's School Standards and Framework Act 1998, grammar schools were for the first time to be designated by statutory instrument.[27][28] The Act also defined a procedure by which local communities could petition for a ballot for an end to selection at schools.[29][30] Petitions were launched in several areas, but only one received the signatures of 20% of eligible parents, the level needed to trigger a ballot.[31] Thus the only ballot held to date was for Ripon Grammar School in 2000, when parents rejected change by a ratio of 2 to 1.[32] These arrangements were condemned by the Select Committee for Education and Skills as being ineffective and a waste of time and resources.[33]

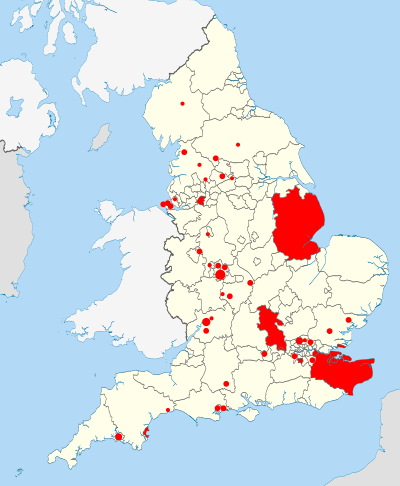

There remain 163 grammar schools in England (out of some 3,000 state secondaries in total).[34] Only a few areas have kept a formal grammar school system along the lines of the Tripartite System. In these areas, the eleven plus exam is used solely to identify a subset of children (around 25%) considered suitable for grammar education. When a grammar school has too many qualified applicants, other criteria are used to allocate places, such as siblings, distance or faith. Such systems still exist in Buckinghamshire, Rugby and Stratford districts of Warwickshire, the Salisbury district of Wiltshire and most of Lincolnshire, Kent, Reading and Medway.[35][36] Of metropolitan areas, Trafford and most of Wirral are selective.[37][38]

In other areas, grammar schools survive mainly as very highly selective schools in an otherwise comprehensive county, for example in several of the outer boroughs of London. These schools are often heavily oversubscribed, and award places in rank order of performance in their entry tests. In some LEAs, as many as 10–15% of 11-year-olds may attend grammar schools (for example in Gloucestershire), but in other LEAs it is as low as 2%. These very highly selective schools also tend to dominate the top positions in performance tables.[39]

Further radical change was opposed by both Conservative and Labour governments until September 2016. Although many on the left argue that the existence of selective schools undermines the comprehensive structure, Labour governments have delegated decisions on grammar schools to local processes, which have not yet resulted in any changes. Moreover, government education policy appears to accept the existence of some kind of hierarchy in secondary education, with specialist schools, beacon schools, academies and similar initiatives proposed as ways of raising standards. Many grammar schools have featured in these programmes, and a lower level of selection is permitted at specialist schools.[40][41]

In September 2016, prime minister Theresa May reversed the previous Conservative Party policy against expansion of grammar schools (except to cope with population expansion in wholly selective areas).[42] The government opened a consultation on proposals to allow existing grammar schools to expand and new ones to be set up.[43] The Labour and Liberal Democrat parties remain opposed to any expansion.[42]

Northern Ireland

Attempts to move to a comprehensive system (as in the rest of the United Kingdom) have been delayed by shifts in the administration of Northern Ireland. As a result, Northern Ireland still maintains the grammar school system, with many pupils being entered for academic selection exams similar to the 11-plus. Since the "open enrolment" reform of 1989, these schools (unlike those in England) have been required to accept pupils up to their capacity, which has also increased.[44] By 2006, the 69 grammar schools took 42% of transferring children, and only 7 of them took all of their intake from the top 30% of the cohort.[45]

The 11-plus has long been controversial, and Northern Ireland's political parties have taken opposing positions. Unionists tend to lean towards preserving the grammar schools as they are, with academic selection at the age of 11, whereas nationalist politicians lean towards scrapping the 11-plus, despite vehement protestations from the majority of Catholic Grammar Schools, most notably by the board of governors at Rathmore Grammar School in Finaghy, (a South Belfast suburb) and Lumen Christi (although co-educational) in Derry. The Democratic Unionist Party claimed to have ensured the continuation of the grammar school system in the Province as part of the St Andrews Agreement in October 2006. By contrast, Sinn Féin claims to have secured the abolition of the 11-plus and a veto over any system which might follow it.

The last government-run 11-plus exam was held in 2008 (for 2009 entry),[46] but the Northern Ireland Assembly has not been able to agree on a replacement system for secondary transfer. The grammar schools have organised groupings to run their own tests, the Post-Primary Transfer Consortium (mostly Catholic schools) and the Association for Quality Education.[47][48][49] The Northern Ireland Commission for Catholic Education has accepted continued selection at Catholic grammar schools as a temporary measure, but wishes them to end the practice by 2012.[50][51] As of September 2019, the practice continues.

In other countries or regions

Grammar schools were established in various British territories, and have developed in different ways since those territories became independent.

Australia

In the mid-19th century, private schools were established in the Australian colonies to spare the wealthy classes from sending their sons to schools in Britain. These schools took their inspiration from English public schools, and often called themselves "grammar schools".[52] Early examples include Launceston Grammar School (1846), Pulteney Grammar School (1847), Geelong Grammar School (1855), Melbourne Grammar School (1858) and Hale School (1858).

With the exception of the non-denominational Sydney Grammar School (1857) and Queensland grammar schools, all the grammar schools established in the 19th century were attached to the Church of England (now the Anglican Church of Australia). In Queensland, the Grammar Schools Act 1860 provided for the state-assisted foundation of non-denominational grammar schools. Beginning with Ipswich Grammar School (1863), ten schools were founded, of which eight still exist.[53] They include Brisbane Girls Grammar School (1875), the first of several grammar schools for girls in Australia.[54]

In the 1920s grammar schools of other denominations were established, including members of the Associated Grammar Schools of Victoria,[55] and the trend has continued to the present day. Today, the term is defined only in Queensland legislation.[53] Throughout the country, "grammar schools" are generally high-cost private schools.

The nearest equivalents of contemporary English grammar schools are selective schools. The New South Wales public education system operates 19 selective public schools which resemble the English grammar-school system insofar as they engage in academic selection by way of centralised examination, they do not charge tuition fees and they are recipients of a greater degree of public funding per pupil than is afforded to non-selective government schools.

Ontario

Grammar schools provided secondary education in Ontario until 1871.

The first lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada, John Graves Simcoe, advocated grammar schools for the colony to save the wealthy from sending their sons to the United States to be educated, but was unable to convince his superiors in London. He did however make a grant enabling John Stuart to set up Kingston Grammar School in 1795.[56][57] After several abortive attempts to raise funding, the District Schools Act of 1807 provided support for one grammar school teacher in each district (of which there were then eight), but they were then left to their own devices. Finding the grammar schools unsuitable as preparation for university, lieutenant-governor Sir John Colborne founded Upper Canada College as a superior grammar school.[58]

Legislation in 1839 allowed for more than one grammar school in a district, triggering a rapid but unstructured growth in numbers over the following two decades, rising to 86 in 1861. The schools became more independent of the Church of England, and also began to admit girls. However, the schools were unsupervised, often underfunded and of varying standards. Some, like Tassie's School in Galt provided a traditional classical education, while many provided a basic education of poor quality.[59] Chief Superintendent of Education Egerton Ryerson attempted to reform the schools in the 1850s and 1860s, moving control of the schools from counties (the former districts) to city authorities, securing their funding and introducing inspectors. However, his efforts to convert the schools into classical schools for only boys were unsuccessful.[60] In recognition of the broad curricula offered, grammar schools were redesignated as high schools by the Act to Improve the Common and Grammar Schools of the Province of Ontario of 1871.[61] Schools able to offer classical studies were given additional funding as collegiate institutes.[62]

Hong Kong

Mainstream schools in Hong Kong reflect the post-war British grammar system, focusing on a traditional curriculum rather than vocational subjects.[63]

Ireland

Education in Ireland has traditionally been organised on denominational lines. Grammar schools along the lines of those in Great Britain were set up for members of the Church of Ireland prior to its disestablishment in 1871. Some schools remain, as private schools catering largely for Protestant students. These are often fee-paying and accommodate boarders, given the scattered nature of the Protestant population in much of Ireland. Such schools include Bandon Grammar School,[64] Drogheda Grammar School, Dundalk Grammar School and Sligo Grammar School.[65] Others are among the many former fee-paying schools absorbed into larger state-funded community schools founded since the introduction of universal secondary education in the Republic by minister Donogh O'Malley in September 1967. Examples include Cork Grammar School, replaced by Ashton Comprehensive School in 1972.[66]

Malaysia

Malaysia has a number of grammar schools, a majority of which were established when the country was under the British. They are generally not known as "grammar schools" but are similarly selective in their intake. Among the best known being the Penang Free School, the Victoria Institution (Kuala Lumpur), Malay College Kuala Kangsar, the English College (Johor Bahru), King George V School (Seremban) and St George's Institution (Taiping). Mission schools set up by various Christian denominations paralleled the selective state school albeit not with the same degree of selectivity. Notable mission schools include the La Sallian family of schools and those set up by the Marist Brothers and Methodist missionaries. Before the 1970s when Malay was made the medium of instruction, many such selective schools became known for providing excellent English-medium education and have produced many notable alumni, including former Prime Minister of Malaysia Najib Tun Razak (St. John's Institution) and all five of his predecessors.

Singapore

Singapore was established as a Crown Colony, and the term "grammar school" was used since 1819 among the English community. The English, and later, the Scottish, set up cathedrals, churches, and elite grammar schools for the upper class. Initially, this was a racially segregated colonial system.

The British then opened up their schools to children from English mixed marriages, or to those with English descent. During the late colonial period, these schools expanded and also schooled descendants of the very few mixed English and Straits-Chinese families, and descendants of some rich Straits-born Chinese merchant class families, who were educated in Oxbridge or had London trade ties. Initially these schools were run exactly like their counterparts in England, and taught by the English.

The oldest of these, Raffles Institution, was founded in 1823 by Sir Stamford Raffles to educate sons born and living in the Crown Colony, often to fathers in Crown colonial service. Single-sex classes were set up for daughters of the British ruling class in 1844, and later became Raffles Girls' School, officially founded in 1879. After independence it became the Raffles Girls' School (Primary School), distinct from the branch school established by the local government after independence, the Raffles Girls' School (Secondary School).

The French Roman Catholic Orders later opened up their ministries and boarding schools to children of mixed marriages, and racial segregation was also relaxed to some extent in the English schools. The French Catholic missions and schools, but not the English schools, also accepted orphans, foundlings, and illegitimate children abandoned by mothers ostracized for breaching racial purity laws.

The CHIJMES building has commemorative plaques for these abandoned babies. The children were termed "children of God" and raised as Catholics. When laws banning polygamy became strictly enforced in Singapore after 1965, these schools extended their English-speaking classes to girls from families of any socio-economic background.

The British grammar schools in Singapore imitated much of this education system, with Catholicism replaced by Anglicanism. Later the Anglican High School of Singapore was set up.

Australian Methodist missionaries started UK-style grammar schools with American and British Methodist church funds. They founded the Anglo-Chinese School (1886) and Methodist Girls' School (1887).

When Singapore became independent from the United Kingdom, the Singapore government established publicly funded bilingual schools based on the existing grammar school system. Since the 1960s their mission was to provide a high-quality elite education to the top 10% in national annual IQ tests, regardless of socio-economic background. These bilingual schools were influenced by the US educational system, and termed "high schools" rather than "grammar schools". Other, less elitist, state schools were called simply "secondary schools", similar to the UK equivalent of "comprehensive schools". High schools include Dunman High School (co-educational), Nanyang Girls' High School, Maris Stella High School (for boys only) and Catholic High School (all-boys). Within these schools there are academically top classes, the very competitive Scholars' class or "A" class. Graduates tend to become part of the upper class. These schools recruit pupils worldwide, particularly from large emerging Asian economies. Recruitment is carried out under the auspices of the Special Assistant Plan Scholars programme, the ASEAN Scholars programme, and the India and China Scholars programmes. Gifted pupils, such as winners of Mathematical Olympiads, international violin and piano competitions, Physics Olympiads and child inventors are particularly sought after.

In addition to religious missions and the new high schools, the less selective Singapore Chinese Girls' School was set up by several Peranakan business and community leaders.

The Ministry of Education published annual rankings, but discontinued them after criticism of excessive academic stress placed on schoolchildren, some of whom committed suicide in response to perceived failure.

After the 1990s all schools were integrated into a unified national school system, but the elite schools distinguished themselves by descriptions such as "independent" or "autonomous".

United States

Grammar schools on the English and later British models were founded during the colonial period, the first being the Boston Latin School, founded as the Latin Grammar School in 1635.[67][68] In 1647 the Massachusetts Bay Colony enacted the Old Deluder Satan Law, requiring any township of at least 100 households to establish a grammar school, and similar laws followed in the other New England colonies. These schools initially taught young men the classical languages as a preparation for university, but by the mid-18th century many had broadened their curricula to include practical subjects. Nevertheless, they declined in popularity owing to competition from the more practical academies.[69]

The name "grammar school" was adopted by public schools for children from 10 to 14 years of age, following a primary stage from 5 to 9 years of age. These types were gradually combined around 1900 to form elementary schools, which were also known as "grammar schools".[69][70]

An analogous concept to the contemporary English grammar school is the magnet school, a state-funded secondary institution that may select students from a given school district according to academic criteria.[71]

New Zealand

In New Zealand, a small number of schools are named "grammar schools" and follow the academic and cultural traditions established in the United Kingdom. Grammar schools were established only in Auckland, and all originally came under the authority of the Auckland Grammar Schools' Board. Auckland's grammar schools share a common line of descent from the British grammar school system, with a strong focus on academics and traditional British sports. Originally these schools used entry assessments and selected academic students from across New Zealand. The schools mentioned below all share the school motto: "Per Angusta Ad Augusta". They also share the same icon/logo, the "Auckland Grammar Lion". Today, all grammar schools in New Zealand are non-selective state schools, although they use school donations to supplement their government funding. Within the Ministry of Education, they are regarded as any other secondary institutions.

New Zealand did not establish a state education system until 1877. The absence of a national education system meant that the first sizeable secondary education providers were grammar schools and other private institutions. The first grammar school in New Zealand, Auckland Grammar School, was established in 1850 and formally recognised as an educational establishment in 1868 through the Auckland Grammar School Appropriation Act. In 1888 Auckland Girls' Grammar School was established. In 1917 Auckland Grammar School's sister school was established—Epsom Girls' Grammar School. In 1922 Mount Albert Grammar School was established as part of Auckland Grammar School. Since then the two schools have become separate institutions. Takapuna Grammar School was established in 1927 and was the first co-educational grammar school to be established in New Zealand.

See also

References

- W.H. Hadow, ed. (1926). The Education of the Adolescent. London: HM Stationery Office. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- Peter Gordon; Denis Lawton (2003). Dictionary of British Education. London: Woburn Press.

- Will Spens, ed. (1938). Secondary education with special reference to grammar schools and technical high schools. London: HM Stationery Office. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- Rev. T.A. Walker (1907–21). "Chapter XV. English and Scottish Education. Universities and Public Schools to the Time of Colet". In A. W. Ward; A. R. Waller (eds.). Volume II: English. The End of the Middle Ages. The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- J. F. A. Mason, The Borough of Bridgnorth 1157–1957 (Bridgnorth, 1957), 12, 36

- Geoffrey Walford (1993). "Girls' Private Schooling: Past and Present". In Geoffrey Walford (ed.). The Private Schooling of Girls: Past and Present. London: The Woburn Press. pp. 9–32.

- "Educating Shakespeare: School Life in Elizabethan England". The Guild School Association, Stratford-upon-Avon. 2003. Archived from the original on 2 March 2001. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- Samuel Johnson (1755). A Dictionary of the English Language.

- Gillian Sutherland (1990). "Education". In F. M. L. Thompson (ed.). Social Agencies and Institutions. The Cambridge Social History of Britain 1750–1950. vol. 3. pp. 119–169.

- Robert Anderson (2003). "The History of Scottish Education, pre-1980". In T. G. K. Bryce; Walter M. Humes (eds.). Scottish Education: Post-Devolution. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 219–228. ISBN 978-0-7486-0980-2.

- J.H.D. Matthews; Vincent Thompson Jr (1897). "A Short Account of the Free Grammar School at Leeds". The Register of Leeds Grammar School 1820–1896. Leeds: Laycock and Sons. p. xvi.

- Slinn, Sara (2017). The Education of the Anglican Clergy, 1780–1839. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer. pp. 129–169. ISBN 978-1-78327-175-7.

- J.W. Adamson (1907–21). "Chapter XIV. Education". In A. W. Ward; A. R. Waller (eds.). Volume XIV. The Victorian Age, Part Two. The Cambridge History of English and American Literature in 18 Volumes.

- Anthony Sampson (1971). The New Anatomy of Britain. London: Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 139–145.

a few direct-grant schools have acquired a special reputation. The most famous of them is Manchester Grammar School

- Paul Bolton (19 October 2015), Grammar school statistics (PDF), House of Commons Library, retrieved 20 October 2015

- Sampson (1971), p. 143.

- The story of the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) Archived 11 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Qualifications and Curriculum Authority.

- Sampson, A. Anatomy of Britain Today, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1965, p.195

- Pischke, Jörn-Steffen; Manning, Alan (April 2006). "Comprehensive versus Selective Schooling in England in Wales: What Do We Know?". NBER Working Paper No. 12176. doi:10.3386/w12176.

- Ian Schagen; Sandy Schagen (November 2001). "The impact of the structure of secondary education in Slough" (PDF). National Foundation for Educational Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Direct Grant Schools". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 22 March 1978. col. 582W–586W.

- Welcome to the National Grammar Schools Association

- Comprehensive Future

- Campaign for State Education

- Grammar school pupils 'gain no social or emotional advantages' by age 14 The Guardian

- new Labour because Britain deserves better Archived 31 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Labour Party manifesto, 1997.

- The Education (Grammar School Designation) Order 1998, Statutory Instrument 1998 No. 2219, UK Parliament.

- The Education (Grammar School Designation) (Amendment) Order 1999, Statutory Instrument 1999 No. 2456, UK Parliament.

- The Education (Grammar School Ballots) Regulations 1998, Statutory Instrument 1998 No. 2876, UK Parliament.

- "A guide to petitions and ballots about grammar school admissions". Department for Education and Schools. 2000. Archived from the original on 26 February 2005.

- Judith Judd (28 March 2000). "Campaign against 11-plus is faltering". The Independent.

- "Grammar school ballots". teachernet. Archived from the original on 12 April 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- "Select Committee on Education and Skills Fourth Report". UK Parliament. 14 July 2004.

- BBC: Family and education: 8 September 2016

- "Admissions to secondary school 2009 booklet" (PDF). Kent County Council. 2009. p. 4. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- "Secondary admissions". Medway Council. 2010. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- David Jesson (2000). "The Comparative Evaluation of GCSE Value-Added Performance by Type of School and LEA" (PDF). Discussion Papers in Economics 2000/52, Centre for Performance Evaluation and Resource Management, University of York. Retrieved 11 October 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ian Schagen and Sandie Schagen (19 October 2001). "The impact of selection on pupil performance" (PDF). Council of Members Meeting. National Foundation for Educational Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2012.

- Sian Griffiths (18 November 2007). "Grammars show they can compete with best". The Sunday Times. London.

- Richard Garner (1 December 2001). "Anger over Labour's grammar school deal". The Independent.

- Clyde Chitty (16 November 2002). "The Right to a Comprehensive Education". Second Caroline Benn Memorial Lecture. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Heather Stewart; Peter Walker (9 September 2016). "Theresa May to end ban on new grammar schools". Guardian.

- Roberts, Nerys; Long, Robert; Foster, David (3 October 2018). "Recent policy developments: Grammar schools in England". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Eric Maurin; Sandra McNally (August 2007). "Educational Effects of Widening Access to the Academic Track: A Natural Experiment" (PDF). Centre for the Economics of Education, London School of Economics, Discussion Paper 85. Retrieved 4 April 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Caitríona Ruane (31 January 2008). "Education Minister's Statement for the Stormont Education Committee" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- "Minister Ruane outlines education reforms" (Press release). Department of Education, Northern Ireland. 4 December 2007. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.

- Smith, Lisa (17 December 2007). "'Test' schools accept D grade pupils". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013.

- Taggart, Maggie (28 April 2009). "Schools guard against test cheats". BBC.

- Torney, Kathryn (22 August 2009). "Parents put their faith in new entrance tests". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013.

- Torney, Kathryn (3 March 2009). "The Minister is losing control of the schools transfer system". Belfast Telegraph.

- "Professor Tony Gallagher, head of the School of Education at Queen's, answers readers' queries..." Belfast Telegraph. 10 August 2009.

- David McCallum (1990). The Social Production of Merit: Education, Psychology, and Politics in Australia, 1900–1950. Routledge. pp. 41–42, 46. ISBN 978-1-85000-859-0.

- Grammar Schools Act 2016, Queensland Government.

- Marjorie R. Theobald (1996). Knowing Women: Origins of Women's Education in Nineteenth-century Australia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 95–97. ISBN 978-0-521-42004-4.

- McCallum (1990), p. 45.

- Gidney, Robert Douglas; Millar, Winnifred Phoebe Joyce (1990). Inventing secondary education: the rise of the high school in nineteenth-century Ontario. McGill-Queen's Press. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-0-7735-0746-3.

- "Stuart, John". Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online. University of Toronto/Université Laval. 2000. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- Gidney and Millar, pp. 82–84.

- Gidney and Millar, pp. 86–114.

- Gidney and Millar, pp. 150–174.

- "Public School Boards: Reorganization, Division, Consolidation and Growth". Archives of Ontario. Archived from the original on 10 May 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- Gidney and Millar, pp. 196–198.

- Morris, Paul (1991). "Preparing pupils as citizens of the special administrative region of Hong Kong: an analysis of curriculum change and control during the transition period". In Postiglione, Gerard A. (ed.). Education and society in Hong Kong: toward one country and two systems. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 117–145. ISBN 978-0-87332-743-5.

- "Bandon Grammar School". Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- "About the school". Sligo Grammar School. Retrieved 13 February 2007.

The school is one of a small number of schools in the Republic of Ireland under Church of Ireland management

- "Ashton School: history". Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 13 February 2007.

Ashton School, as a comprehensive school, was founded in September 1972 when Rochelle School and Cork Grammar School merged on the Grammar School site.

- "BLS History". Boston Latin School. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- "Boston Latin School". Britannica Online Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 13 September 2008.

- Charles Dorn (2003). "Grammar School". In Paula S. Fass (ed.). Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood in History and Society. New York: Macmillan Reference Books. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- See definitions of grammar school in most U.S. dictionaries.

- Cyril Taylor; Conor Ryan (2013). Excellence in Education: The Making of Great Schools. Routledge. p. 229. ISBN 978-1-136-61021-9.