Polytetrafluoroethylene

Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) is a synthetic fluoropolymer of tetrafluoroethylene that has numerous applications. The well-known brand name of PTFE-based formulas is Teflon by Chemours.[2] Chemours was a spin-off from DuPont, which originally discovered the compound in 1938.[2] Another popular brand name of PTFE is Syncolon by Synco Chemical Corporation.[3]

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Poly(tetrafluoroethylene)[1] | |

| Other names

Syncolon, Fluon, Poly(tetrafluroethene), Poly(difluoromethylene), Poly(tetrafluoroethylene), teflon | |

| Identifiers | |

| Abbreviations | PTFE |

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.120.367 |

| KEGG | |

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| Properties | |

| (C2F4)n | |

| Density | 2200 kg/m3 |

| Melting point | 600 F, 327 °C |

| Thermal conductivity | 0.25 W/(m·K) |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

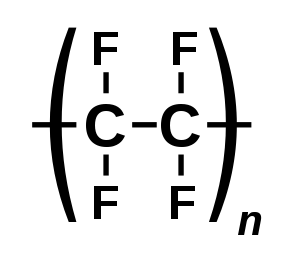

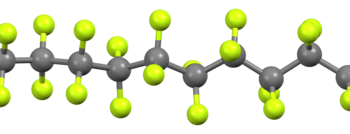

PTFE is a fluorocarbon solid, as it is a high molecular weight compound consisting wholly of carbon and fluorine. PTFE is hydrophobic: neither water nor water-containing substances wet PTFE, as fluorocarbons demonstrate mitigated London dispersion forces due to the high electronegativity of fluorine. PTFE has one of the lowest coefficients of friction of any solid.

PTFE is used as a non-stick coating for pans and other cookware. It is non-reactive, partly because of the strength of carbon–fluorine bonds, and so it is often used in containers and pipework for reactive and corrosive chemicals. Where used as a lubricant, PTFE reduces friction, wear, and energy consumption of machinery. It is commonly used as a graft material in surgical interventions. It is also frequently employed as coating on catheters; this interferes with the ability of bacteria and other infectious agents to adhere to catheters and cause hospital-acquired infections.

History

PTFE was accidentally discovered in 1938 by Roy J. Plunkett while he was working in New Jersey for DuPont. As Plunkett attempted to make a new chlorofluorocarbon refrigerant, the tetrafluoroethylene gas in its pressure bottle stopped flowing before the bottle's weight had dropped to the point signaling "empty." Since Plunkett was measuring the amount of gas used by weighing the bottle, he became curious as to the source of the weight, and finally resorted to sawing the bottle apart. He found the bottle's interior coated with a waxy white material that was oddly slippery. Analysis showed that it was polymerized perfluoroethylene, with the iron from the inside of the container having acted as a catalyst at high pressure.[4] Kinetic Chemicals patented the new fluorinated plastic (analogous to the already known polyethylene) in 1941,[5] and registered the Teflon trademark in 1945.[6][7]

By 1948, DuPont, which founded Kinetic Chemicals in partnership with General Motors, was producing over two million pounds (900 tons) of Teflon brand PTFE per year in Parkersburg, West Virginia.[8] An early use was in the Manhattan Project as a material to coat valves and seals in the pipes holding highly reactive uranium hexafluoride at the vast K-25 uranium enrichment plant in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.[9]

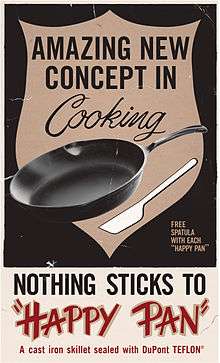

In 1954, Collette Grégoire, the wife of French engineer Marc Grégoire, urged him to try the material he had been using on fishing tackle on her cooking pans. He subsequently created the first PTFE-coated, non-stick pans under the brand name Tefal (combining "Tef" from "Teflon" and "al" from aluminium).[10] In the United States, Marion A. Trozzolo, who had been using the substance on scientific utensils, marketed the first US-made PTFE-coated pan, "The Happy Pan", in 1961.[11] Non-stick cookware has since become a common household product, nowadays offered by hundreds of manufacturers across the world.

In the 1990s, it was found that PTFE could be radiation cross-linked above its melting point in an oxygen-free environment.[12] Electron beam processing is one example of radiation processing. Cross-linked PTFE has improved high-temperature mechanical properties and radiation stability. This was significant because, for many years, irradiation at ambient conditions has been used to break down PTFE for recycling.[13] This radiation-induced chain scission allows it to be more easily reground and reused.

Production

PTFE is produced by free-radical polymerization of tetrafluoroethylene.[14] The net equation is

- n F2C=CF2 → −(F2C−CF2)n−

Because tetrafluoroethylene can explosively decompose to tetrafluoromethane and carbon, special apparatus is required for the polymerization to prevent hot spots that might initiate this dangerous side reaction. The process is typically initiated with persulfate, which homolyzes to generate sulfate radicals:

- [O3SO−OSO3]2− ⇌ 2 SO4•−

The resulting polymer is terminated with sulfate ester groups, which can be hydrolyzed to give OH end-groups.[15]

Because PTFE is poorly soluble in almost all solvents, the polymerization is conducted as an emulsion in water. This process gives a suspension of polymer particles. Alternatively, the polymerization is conducted using a surfactant such as PFOS.

Properties

PTFE is a thermoplastic polymer, which is a white solid at room temperature, with a density of about 2200 kg/m3. According to research, its melting point is 600 K (327 °C; 620 °F).[16] It maintains high strength, toughness and self-lubrication at low temperatures down to 5 K (−268.15 °C; −450.67 °F), and good flexibility at temperatures above 194 K (−79 °C; −110 °F).[17] PTFE gains its properties from the aggregate effect of carbon-fluorine bonds, as do all fluorocarbons. The only chemicals known to affect these carbon-fluorine bonds are highly reactive metals like the alkali metals, and at higher temperatures also such metals as aluminium and magnesium, and fluorinating agents such as xenon difluoride and cobalt(III) fluoride.[18] At temperatures above 650–700 °C (1,200–1,290 °F) PTFE undergoes depolymerization.[19]

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Density | 2200 kg/m3 |

| Glass temperature | 114.85 °C (238.73 °F; 388.00 K)[20] |

| Melting point | 326.85 °C (620.33 °F; 600.00 K) |

| Thermal expansion | 112–125×10−6 K−1[21] |

| Thermal diffusivity | 0.124 mm2/s[22] |

| Young's modulus | 0.5 GPa |

| Yield strength | 23 MPa |

| Bulk resistivity | 1018 Ω·cm[23] |

| Coefficient of friction | 0.05–0.10 |

| Dielectric constant | ε = 2.1, tan(δ) < 5×10−4 |

| Dielectric constant (60 Hz) | ε = 2.1, tan(δ) < 2×10−4 |

| Dielectric strength (1 MHz) | 60 MV/m |

| Magnetic susceptibility (SI, 22 °C) | −10.28×10−6[24] |

The coefficient of friction of plastics is usually measured against polished steel.[25] PTFE's coefficient of friction is 0.05 to 0.10,[16] which is the third-lowest of any known solid material (BAM being the first, with a coefficient of friction of 0.02; diamond-like carbon being second-lowest at 0.05). PTFE's resistance to van der Waals forces means that it is the only known surface to which a gecko cannot stick.[26] In fact, PTFE can be used to prevent insects from climbing up surfaces painted with the material. PTFE is so slippery that insects cannot get a grip and tend to fall off. For example, PTFE is used to prevent ants from climbing out of formicaria.

Because of its chemical inertness, PTFE cannot be cross-linked like an elastomer. Therefore, it has no "memory" and is subject to creep. Because of its superior chemical and thermal properties, PTFE is often used as a gasket material within industries that require resistance to aggressive chemicals such as pharmaceuticals or chemical processing.[27] However, because of the propensity to creep, the long-term performance of such seals is worse than for elastomers that exhibit zero, or near-zero, levels of creep. In critical applications, Belleville washers are often used to apply continuous force to PTFE gaskets, thereby ensuring a minimal loss of performance over the lifetime of the gasket.[28]

Processing

Processing PTFE can be difficult and expensive, because the high melting temperature, 327 °C (621 °F), is above the initial decomposition temperature, 200 °C (392 °F).[29] Even when melted, PTFE does not flow, but instead behaves as a gel due to the absence of crystalline phase[30] and high melt viscosity.[31]

Some PTFE parts are made by cold-moulding, a form of compression molding.[32] Here, fine powdered PTFE is forced into a mould under high pressure (10–100 MPa).[32] After a settling period, lasting from minutes to days, the mould is heated at 360 to 380 °C (680 to 716 °F),[32] allowing the fine particles to fuse into a single mass.[33]

Applications and uses

_(cropped).jpg)

The major application of PTFE, consuming about 50% of production, is for the insulation of wiring in aerospace and computer applications (e.g. hookup wire, coaxial cables). This application exploits the fact that PTFE has excellent dielectric properties,[34] especially at high radio frequencies,[34] making it suitable for use as an excellent insulator in connector assemblies and cables, and in printed circuit boards used at microwave frequencies. Combined with its high melting temperature, this makes it the material of choice as a high-performance substitute for the weaker and lower-melting-point polyethylene commonly used in low-cost applications.

In industrial applications, owing to its low friction, PTFE is used for plain bearings, gears, slide plates, seals, gaskets, bushings[35], and more applications with sliding action of parts, where it outperforms acetal and nylon.[36]

Its extremely high bulk resistivity makes it an ideal material for fabricating long-life electrets, the electrostatic analogues of permanent magnets.

PTFE film is also widely used in the production of carbon fiber composites as well as fiberglass composites, notably in the aerospace industry. PTFE film is used as a barrier between the carbon or fiberglass part being built, and breather and bagging materials used to incapsulate the bondment when debulking (vacuum removal of air from between layers of laid-up plies of material) and when curing the composite, usually in an autoclave. The PTFE, used here as a film, prevents the non-production materials from sticking to the part being built, which is sticky due to the carbon-graphite or fiberglass plies being pre-pregnated with bismaleimide resin. Non-production materials such as Teflon, Airweave Breather and the bag itself would be considered F.O.D. (foreign object debris/damage) if left in layup.

Because of its extreme non-reactivity and high temperature rating, PTFE is often used as the liner in hose assemblies, expansion joints, and in industrial pipe lines, particularly in applications using acids, alkalis, or other chemicals. Its frictionless qualities allow improved flow of highly viscous liquids, and for uses in applications such as brake hoses.

Gore-Tex is a brand of expanded PTFE (ePTFE), a material incorporating a fluoropolymer membrane with micropores. The roof of the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome in Minneapolis, US, was one of the largest applications of PTFE coatings. 20 acres (81,000 m2) of the material was used in the creation of the white double-layered PTFE-coated fiberglass dome.

PTFE is often found in musical instrument lubrication product; most commonly, valve oil.

PTFE is used in some aerosol lubricant sprays, including in micronized and polarized form. It is notable for its extremely low coefficient of friction, its hydrophobia (which serves to inhibit rust), and for the dry film it forms after application, which allows it to resist collecting particles that might otherwise form an abrasive paste.[37]

PTFE (Teflon) is best known for its use in coating non-stick frying pans and other cookware, as it is hydrophobic and possesses fairly high heat resistance.

The sole plates of some clothes irons are coated with PTFE (Teflon).[38]

Other niche applications include:

- It is often found in ski bindings as a non-mechanical AFD (anti-friction device)

- It can be stretched to contain small pores of varying sizes and is then placed between fabric layers to make a waterproof, breathable fabric in outdoor apparel.[39]

- It is used widely as a fabric protector to repel stains on formal school-wear, like uniform blazers.[40]

- It is frequently used as a lubricant to prevent captive insects and other arthropods from escaping.

- It is used as a film interface patch for sports and medical applications, featuring a pressure-sensitive adhesive backing, which is installed in strategic high friction areas of footwear, insoles, ankle-foot orthosis, and other medical devices to prevent and relieve friction-induced blisters, calluses and foot ulceration.[41]

- Expanded PTFE membranes have been used in trials to assist trabeculectomy surgery to treat glaucoma.[42]

- Powdered PTFE is used in pyrotechnic compositions as an oxidizer with powdered metals such as aluminium and magnesium. Upon ignition, these mixtures form carbonaceous soot and the corresponding metal fluoride, and release large amounts of heat. They are used in infrared decoy flares and as igniters for solid-fuel rocket propellants.[43] Aluminium and PTFE is also used in some thermobaric fuel compositions.

- Powdered PTFE is used in a suspension with a low-viscosity, azeotropic mixture of siloxane ethers to create a lubricant for use in twisty puzzles.[44]

- In optical radiometry, sheets of PTFE are used as measuring heads in spectroradiometers and broadband radiometers (e.g., illuminance meters and UV radiometers) due to PTFE's capability to diffuse a transmitting light nearly perfectly. Moreover, optical properties of PTFE stay constant over a wide range of wavelengths, from UV down to near infrared. In this region, the ratio of its regular transmittance to diffuse transmittance is negligibly small, so light transmitted through a diffuser (PTFE sheet) radiates like Lambert's cosine law. Thus PTFE enables cosinusoidal angular response for a detector measuring the power of optical radiation at a surface, e.g. in solar irradiance measurements.

- Certain types of bullets are coated with PTFE to reduce wear on the rifling of firearms that uncoated projectiles would cause. PTFE itself does not give a projectile an armor-piercing property.[45]

- Its high corrosion resistance makes PTFE useful in laboratory environments, where it is used for lining containers, as a coating for magnetic stirrers, and as tubing for highly corrosive chemicals such as hydrofluoric acid, which will dissolve glass containers. It is used in containers for storing fluoroantimonic acid, a superacid.[46]

- PTFE tubes are used in gas-gas heat exchangers in gas cleaning of waste incinerators. Unit power capacity is typically several megawatts.

- PTFE is widely used as a thread seal tape in plumbing applications, largely replacing paste thread dope.

- PTFE membrane filters are among the most efficient industrial air filters. PTFE-coated filters are often used in dust collection systems to collect particulate matter from air streams in applications involving high temperatures and high particulate loads such as coal-fired power plants, cement production and steel foundries.[47]

- PTFE grafts can be used to bypass stenotic arteries in peripheral vascular disease if a suitable autologous vein graft is not available.

- Many bicycle lubricants and greases contain PTFE and are used on chains and other moving parts subjected to frictional forces (such as hub bearings).

- EPTFE is used for some types of dental floss.

- PTFE can also be used for dental fillings, to isolate the contacts of the anterior tooth so the filling materials will not stick to the adjacent tooth.[48][49]

- PTFE sheets are used in the production of butane hash oil due to its non-stick properties and resistance to non-polar solvents.[50]

- PTFE, associated with a slightly textured laminate, makes the plain bearing system of a Dobsonian telescope.

- PTFE is widely used as a non-stick coating for food processing equipment;[51] dough hoppers, mixing bowls, conveyor systems, rollers, and chutes. PTFE can also be reinforced where abrasion is present – for equipment processing seeded or grainy dough for example.[52]

- PTFE has been experimented with for electroless nickel plating.

- PTFE tubing is used for Bowden tubing in 3D printers because its low friction allows the extruder stepper motor to push filament through it more easily.

- PTFE is commonly used in aftermarket add-on mouse feet for gaming mice to reduce friction of the mouse against the mouse pad, resulting in a smoother glide.

- PTFE foils are commonly used with laserprinters everywhere, in their fuser unit, wrapped around the heater element(s) and as well on the opposite pressure roller to prevent any kind of sticking to it (neither the printed paper nor toner waste)

Safety

Pyrolysis of PTFE is detectable at 200 °C (392 °F), and it evolves several fluorocarbon gases and a sublimate. An animal study conducted in 1955 concluded that it is unlikely that these products would be generated in amounts significant to health at temperatures below 250 °C (482 °F).[29]Products like non-stick coated cookware have had their PFOA removed since 2013[53] and prior to this products containing PFOA weren't found to be major sources of exposure.[54]

While PTFE is stable and nontoxic at lower temperatures, it begins to deteriorate after the temperature of cookware reaches about 260 °C (500 °F), and decomposes above 350 °C (662 °F).[55] The degradation by-products can be lethal to birds,[56] and can cause flu-like symptoms[57] in humans—see polymer fume fever. Meat is usually fried between 204 and 232 °C (399 and 450 °F), and most oils start to smoke before a temperature of 260 °C (500 °F) is reached, but there are at least two cooking oils (refined safflower oil at 265 °C (509 °F) and avocado oil at 271 °C (520 °F)) that have a higher smoke point. However these cases of polymer fume fever were mostly present in people who had cooked at 390 °C (734 °F) for ⪰4 hours.[54]

Several recent legislative and regulatory efforts across the US to address polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have focused on limiting levels in drinking water. However, there has been relatively little conversation about the presence of these chemicals in our everyday lives and the public’s sheer exposure to PFAS through primary contact from commercial products used in our everyday lives. Several peer reviewed studies have shown that the mean and median concentration of PFOA in household dust in the US was found to be between approximately 10,000 and 50,000 parts per trillion (ppt). These studies highlight the fact that there is significantly more PFOA in the ambient dust in the average home than the levels currently being discussed as thresholds for drinking water. Because PFAS is in the products we use, is transported through air and water and has been found in the food we eat, there are numerous public exposure pathways for PFAS beyond drinking water. [58]

Drinking water treatment systems, wastewater treatment facilities, and municipal solid waste landfills are not “producers” or users of PFAS, and none of these essential public service providers utilize or profit from PFAS chemicals. Rather, they are “receivers” of these chemicals used by manufacturers and everyday consumers, and merely convey and/or manage the traces of PFAS coming into our systems daily. [59]

In response to the phase out of PFAS use and appropriate source control and product substitution, continued reduction of trace levels is anticipated. It is important to note that PFAS are also found in paper mill residuals, digestates, composts, and soils. Given the ubiquity of PFAS, and the comparative background levels which may be found in wastewater, biosolids, and leachates, setting requirements near analytical detection limits on these sources may not provide a discernable benefit to protecting public health. [60]

Ecotoxicity

Sodium trifluoroacetate and the similar compound chlorodifluoroacetate can both be generated when PTFE undergoes thermolysis, as well as producing longer chain polyfluoro- and/or polychlorofluoro- (C3-C14) carboxylic acids which may be equally persistent. Some of these products have recently been linked with possible adverse health and environmental impacts and are being phased out of the US market.[61]

Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) is sometimes used in the process of making PTFE/Teflon, although it is burned off during this process and is not usually present in significant quantities in the resultant PTFE.

PFOA

Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA, or C8) has been used as a surfactant in the emulsion polymerization of PTFE, although several manufacturers have entirely discontinued its use.

PFOA persists indefinitely in the environment.[62] PFOA has been detected in the blood of more than 98% of the general US population in the low and sub-parts per billion range, and levels are higher in chemical plant employees and surrounding subpopulations. PFOA and PFOS are found in every American person’s blood stream in the parts per billion range, though those concentrations have decreased by 70% for PFOA and 84% for PFOS between 1999 and 2014, which coincides with the end of the production and phase out of PFOA and PFOS in the US. [63][64] The general population has been exposed to PFOA through massive dumping of C8 waste into the ocean and near the Ohio River Valley.[65][66][67] PFOA has been detected in industrial waste, stain-resistant carpets, carpet cleaning liquids, house dust, microwave popcorn bags, water, food and Teflon cookware.

As a result of a class-action lawsuit and community settlement with DuPont, three epidemiologists conducted studies on the population surrounding a chemical plant that was exposed to PFOA at levels greater than in the general population. The studies concluded that there was an association between PFOA exposure and six health outcomes: kidney cancer, testicular cancer, ulcerative colitis, thyroid disease, hypercholesterolemia (high cholesterol), and pregnancy-induced hypertension.[68]

Overall, PTFE cookware is considered a minor exposure pathway to PFOA.[69]

Similar polymers

The Teflon trade name is also used for other polymers with similar compositions:

- Perfluoroalkoxy alkane (PFA)

- Fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP)

These retain the useful PTFE properties of low friction and nonreactivity, but are also more easily formable. For example, FEP is softer than PTFE and melts at 533 K (260 °C; 500 °F); it is also highly transparent and resistant to sunlight.[70]

See also

- BS 4994 PTFE as a thermoplastic lining for dual laminate chemical process plant equipment

- Dark Waters, a film about litigation related to PFOAs

- The Devil We Know documentary on PFOA's health and environmental effects

- ETFE

- Magnesium/Teflon/Viton pyrolant thermite composition

- Polymer adsorption

- Polymer fume fever

- Superhydrophobic coating

References

- "poly(tetrafluoroethylene) (CHEBI:53251)". ebi.ac.uk. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- "Teflon | Chemours Teflon Nonstick Coatings and Additives". www.chemours.com. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- "The Super Lube® Story". www.super-lube.com. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- "Roy J. Plunkett". Science History Institute. June 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- US 2230654, Plunkett, Roy J, "Tetrafluoroethylene polymers", issued 4 February 1941

- "History Timeline 1930: The Fluorocarbon Boom". DuPont. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- "Roy Plunkett: 1938". Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- American Heritage of Invention & Technology, Fall 2010, vol. 25, no. 3, p. 42

- Rhodes, Richard (1986). The Making of the Atomic Bomb. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 494. ISBN 0-671-65719-4. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- "Teflon History ", home.nycap.rr.com, Retrieved 25 January 2009.

- Robbins, William (21 December 1986) "Teflon Maker: Out Of Frying Pan Into Fame ", New York Times, Retrieved 21 December 1986 (Subscription)

- Sun, J.Z.; et al. (1994). "Modification of polytetrafluoroethylene by radiation—1. Improvement in high temperature properties and radiation stability". Radiat. Phys. Chem. 44 (6): 655–679. Bibcode:1994RaPC...44..655S. doi:10.1016/0969-806X(94)90226-7.

- Electron Beam Processing of PTFE E-BEAM Services website. Accessed 21 May 2013

- Puts, Gerard J.; Crouse, Philip; Ameduri, Bruno M. (28 January 2019). "Polytetrafluoroethylene: Synthesis and Characterization of the Original Extreme Polymer". Chemical Reviews. 119 (3): 1763–1805. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00458. PMID 30689365.

- Carlson, D. Peter and Schmiegel, Walter (2000) "Fluoropolymers, Organic" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a11_393

- Fluoroplastic Comparison – Typical Properties. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- Teflon PTFE Properties Handbook. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- DuPont Teflon Coatings. plastechcoatings.com

- R. J. Hunadi; K. Baum (1982). "Tetrafluoroethylene: A Convenient Laboratory Preparation". Synthesis. 39 (6): 454. doi:10.1055/s-1982-29830.

- Nicholson, John W. (2011). The Chemistry of Polymers (4, Revised ed.). Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 50. ISBN 9781849733915.

- "Reference Tables – Thermal Expansion Coefficients – Plastics". engineershandbook.com.

- Blumm, J.; Lindemann, A.; Meyer, M.; Strasser, C. (2011). "Characterization of PTFE Using Advanced Thermal Analysis Technique". International Journal of Thermophysics. 40 (3–4): 311. Bibcode:2010IJT....31.1919B. doi:10.1007/s10765-008-0512-z.

- "PTFE". Microwaves101.

- Wapler, M. C.; Leupold, J.; Dragonu, I.; von Elverfeldt, D.; Zaitsev, M.; Wallrabe, U. (2014). "Magnetic properties of materials for MR engineering, micro-MR and beyond". JMR. 242: 233–242. arXiv:1403.4760. Bibcode:2014JMagR.242..233W. doi:10.1016/j.jmr.2014.02.005. PMID 24705364.

- Coefficient of Friction (COF) Testing of Plastics. MatWeb Material Property Data. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- "Research into Gecko Adhesion", Berkeley, 2007-10-14. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- "PTFE Sheet". Gasket Resources Inc. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- Davet, George P. "Using Belleville Springs To Maintain Bolt Preload" (PDF). Solon Mfg. Co. Retrieved 18 May 2014.

- Zapp JA, Limperos G, Brinker KC (26 April 1955). "Toxicity of pyrolysis products of 'Teflon' tetrafluoroethylene resin". Proceedings of the American Industrial Hygiene Association Annual Meeting.

- "Free Flow Granular PTFE" (PDF). Inoflon Fluoropolymers. 16 August 2017.

- "COWIE TECHNOLOGY - PTFE: High Thermal Stability". www.cowie.com. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- "Polyflon PTFE Molding Powder" (PDF). Daikin Chemical. 16 August 2017.

- "Unraveling Polymers: PTFE". Poly Fouoro Ltd. 26 April 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- Mishra, Munmaya; Yagci, Yusuf (208). Handbook of Vinyl Polymers: Radical Polymerization, Process, and Technology, Second Edition (2nd, illustrated, revised ed.). CRC Press. p. 574. ISBN 978-0-8247-2595-2. Extract of page 574

- "Teflon Machining & Fabrication | ESPE". www.espemfg.com. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- Mishra & Yagci, p 573

- "What is MicPol?". Lubrication. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- Fers à repasser semelle teflon - Fiche pratique - Le Parisien. Pratique.leparisien.fr. Retrieved on 2016-11-17.

- "A Motorcyclist's Guide To Gore-Tex". Infinity Motorcycles. Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- "Advantages and Disadvantages of Teflon-coated Covert Cloth". The Cutter and Tailor.

- "Film Interface Patch". American Academy of Orthotists & Prosthetists.

- Wang X, Khan R, Coleman A (2015). "Device-modified trabeculectomy for glaucoma". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 12 (12): CD010472. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010472.pub2. PMC 4715269. PMID 26625212.

- Koch, E.-C. (2002). "Metal-Fluorocarbon Pyrolants:III. Development and Application of Magnesium/Teflon/Viton". Propellants, Explosives, Pyrotechnics. 27 (5): 262–266. doi:10.1002/1521-4087(200211)27:5<262::AID-PREP262>3.0.CO;2-8.

- "Lubicle 1". TheCubicle.us. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- "Interview with an inventor of the KTW bullet". NRAction Newsletter. 4 (5). May 1990.

- Pomeroy, Ross (24 August 2013). "The World's Strongest Acids: Like Fire and Ice". Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- "Industrial Air Permits - New Clean Air Regulations And Baghouses". Baghouse.com. 28 May 2012.

- Brown, DDS, Dennis E. "Using Plumber's Teflon Tape to Enhance Bonding Procedures". Dentistry Today.

- Dunn, WJ; et al. (2004). "Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) tape as a matrix in operative dentistry". Operative Dentistry. 29 (4): 470–2. PMID 15279489.

- Rosenthal, Ed (21 October 2014). Beyond Buds (Revised ed.). Quick American Archives. ISBN 978-1936807239.

- "Fluoropolymer PTFE coating services from Surface Technology UK".

- "Fluoropolymer PTFE coating services from Surface Technology UK". Surface Technology. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- "The truth about teflon: are non-stick pans safe?". Better Homes and Gardens. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- "Is Nonstick Cookware Like Teflon Safe to Use?". Healthline. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- "Polytetrafluouroethylene: PTFE Sheets & PTFE Coatings from Porex". www.porex.com. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- "Key Safety Questions About Teflon Nonstick Coatings". DuPont. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- "Key Safety Questions about the Safety of Nonstick Cookware". DuPont.

- http://www.mwra.com/01news/2019/2019-11-PFAS-fact-sheet.pdf

- https://casaweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/National-PFAS-Receivers-Factsheet.pdf

- https://casaweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/National-PFAS-Receivers-Factsheet.pdf

- "Toxnet Has Moved".

- Emerging Contaminants Fact Sheet – Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA). National Service Center for Environmental Publications (Report). United States Environmental Protection Agency. March 2014. p. 1. 505-F-14-001. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- https://casaweb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/National-PFAS-Receivers-Factsheet.pdf

- http://www.mwra.com/01news/2019/2019-11-PFAS-fact-sheet.pdf

- RIch, Nathaniel. "The Lawyer Who Became Dupont's Worst Nightmare". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Blake, Mariah. "Welcome to Beautiful Parkersburg, West Virginia Home to one of the most brazen, deadly corporate gambits in U.S. history". Huffington Post. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- Fellner, Carrie (16 June 2018). "Toxic Secrets: Professor 'bragged about burying bad science' on 3M chemicals". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- Nicole, W. (2013). "PFOA and Cancer in a Highly Exposed Community: New Findings from the C8 Science Panel". Environmental Health Perspectives. 121 (11–12): A340. doi:10.1289/ehp.121-A340. PMC 3855507. PMID 24284021.

- Trudel D, Horowitz L, Wormuth M, Scheringer M, Cousins IT, Hungerbühler K (April 2008). "Estimating consumer exposure to PFOS and PFOA". Risk Anal. 28 (2): 251–69. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.2008.01017.x. PMID 18419647.

- FEP Detailed Properties, Parker-TexLoc, 13 April 2006. Retrieved 10 September 2006.

- PTFE at Holscot Fluoroplastics

Further reading

- Ellis, D.A.; Mabury, S.A.; Martin, J.W.; Muir, D.C.G.; Mabury, S.A.; Martin, J.W.; Muir, D.C.G. (2001). "Thermolysis of fluoropolymers as a potential source of halogenated organic acids in the environment". Nature. 412 (6844): 321–324. Bibcode:2001Natur.412..321E. doi:10.1038/35085548. PMID 11460160.

External links

- "EPA: Compound in Teflon may cause cancer", Tom Costello, NBC News, 29 June 2005. (Flash video required)

- "Teflon chemical cancer risks downplayed?", 30 June 2005

- Plasma Processes and Adhesive Bonding of Polytetrafluoroethylene

(Wayback Machine copy)

(Wayback Machine copy)