Sanday, Orkney

Sanday is one of the inhabited islands of Orkney that lies off the north coast of mainland Scotland. With an area of 50.43 km2 (19.5 sq mi),[3] it is the third largest of the Orkney Islands.[8] The main centres of population are Lady Village and Kettletoft. Sanday can be reached by Orkney Ferries or by plane from Kirkwall on the Orkney Mainland. On Sanday, an on-demand public minibus service allows connecting to the ferry.

| Norse name | Sandey[1][2] |

|---|---|

| Meaning of name | Old Norse: sand island[3] |

An aerial view of the southern coast of Sanday, looking west. Tres Ness and Conninghole are in the foreground. | |

| Location | |

Sanday Sanday shown within Orkney | |

| OS grid reference | HY677411 |

| Coordinates | 59.25°N 2.55°W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Orkney |

| Area | 5,043 ha (19.5 sq mi)[3] |

| Area rank | 21 [4] |

| Highest elevation | The Wart 65 m (213 ft)[5] |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Orkney Islands |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 494[6] |

| Population rank | 22 [4] |

| Population density | 9.8 people/km2[3][6] |

| Largest settlement | Lady |

| References | [7] |

Etymology

The Picts were the pre-Norse inhabitants of Sanday but very few placenames remain from this period.[9] The Norse named the island Sandey[2] or Sand-øy[3] because of the predominance of sandy beaches and this became "Sanday" during the Scots and English speaking periods. The similarly named Sandoy is in the Faroe Islands.

Many names of places and natural features derive from Old Norse. According to Dorward (1995), the placename Kettletoft means "Kettil's croft"[10] although "toft" in this context may mean ""abandoned site of house" from the Norse topt.[11] The suffix -bister found in Sellibister and Overbister is from bólstaðr meaning "dwelling" or "farm".[11] Other common suffixes are -wick and -ness from the Norse vik and nes and meaning "bay" and "headland" respectively.[12] According to Frances Groome, Otterswick was originally known as Odinswic.[13]

Geography and geology

Sanday lies south of North Ronaldsay and east of Eday and Westray. It is divided naturally into two roughly equal halves by Otterswick, a bay which runs in from the north, and Kettletoft Bay in the south. The narrow isthmus between them formed the boundary between the historic parishes Cross and Burness to the west and Lady to the east.[14] The novelist Eric Linklater described Sanday's shape seen from the air as being like that of a giant fossilised bat.[3]

Changing post-glacial sea levels will have much altered the shape of this low-lying island since the last ice age. William Traill described a gale in 1838 which removed 20 hectares (49 acres) of sand in Otterswick Bay. This revealed a dark layer of decayed vegetation under fallen trees up to 60 centimetres (24 in) in diameter. The trees lay "as if felled by a storm" and were visible under the sea for 6.5 kilometres (4.0 mi). A search for these tree remains in the 20th century was unsuccessful.[15]

Inland it is fertile and agricultural and there is some commercial lobster fishing. The underlying geology is predominantly Devonian sediments of the Rousay flagstone group with Eday sandstone in the south east.[16]

There are several small bodies of freshwater on the island including North Loch, Bea Loch near Kettletoft and Roos Loch on the Burness peninsula.[5]

Prehistory

The Neolithic Quoyness chambered cairn, dates from around 2900 BC. An arc of Bronze Age mounds surrounds this cairn on the Elsness peninsula.[17] A large man-made mound at Pool was excavated in the 1980s. This indicated a Neolithic structure made of turf or burnt peat, a later pre-Viking sub-circular structure with pavings and cells, and a Viking stone and turf rectangular building dated to the late 8th or early 9th century. Various implements were also discovered including pre-Norse hipped pins and pottery from both the pre-Viking and Norse periods. A predominance of fish and animal bones suggests the site was used for meat processing.[18] Storms in January 2005 exposed a Bronze Age burnt burial mound at Meur.[19] There are several ruined Iron Age brochs on the island such as the Broch of Wasso, a 5-metre-high (16 ft) mound at Tres Ness.[20]

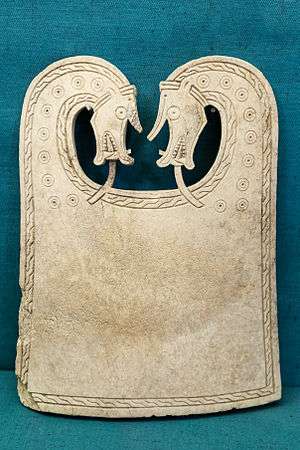

The nature of the culture that built the brochs remains a matter of debate[21] but it is known that later Iron Age Orkney was part of the Pictish kingdom and from at least the mid-6th century onwards that Christianity had spread to the islands.[22] However, the archeological record for this period is sparse[23] and little is known of life on Sanday at this time beyond that which can be assumed from a knowledge of Pictish society elsewhere. The local heritage centre shows a Pictish decorated stone showing a cross.

History

Orkney became part of the Scandinavian polity from perhaps the 9th century onwards. In 1991 the Scar boat burial was discovered on the coast of Sanday near Burness. This Norse-era vessel, which had been 6.5-metre (21 ft) long and 1.5-metre (4.9 ft) wide, had rotted away, leaving more than 300 iron rivets.[24] The enclosure, dated to 875—950 AD, was found to contain the remains of a man, a woman, and a child, along with numerous grave goods. These included a sword, quiver with arrows, bone comb, gaming pieces and the Scar dragon plaque, made from whale bone.[24][25]

During the medieval period Sanday had 36 ouncelands, which may have been divided into two 'huseby' districts for taxation purposes with Lady to the east forming a unit with Stronsay and Cross and Burness to the west being combined with Eday and other isles to the west and north.[14] The main farm for the western district may have been located between Pool Bay and Warsetter at a site called Housay that is now just a mound.[26]

In the mid-17th century an annexe to Blaeu's Atlas Novus of Scotland recorded that Sanday's low lying topography meant that "shipwreck often occurs to those who sail there at night. The inhabitants of Sanday earnestly and often desire this to happen, so that they get a supply of material for fire from the wrecked ships". The writer went on to state that the lack of peat meant that dried seaweed was "saved like treasure" for cooking fires and that only the better-off citizens could afford to bring peat from Eday "over the most fearful sea".[27]

In March 1633, Marion Richart or Layland of Sanday was accused of witchcraft. Her grandson James Fisher said he had seen her and Catrine Miller at an empty house called the House of Howing Greenay, sitting beside the devil in the likeness of a "black man". Other witnesses declared she had charmed a fisherman's bait with the paws of her cat, healed a sick woman with a charm, and charmed milk from cows on Stronsay. She was tried at Kirkwall, found guilty, strangled and burnt.[28]

Writing in the early 18th century, the Rev. John Brand described island life thus:

"Both Men and Women are fashionable in their cloths, no Men here use Plaids, as they do in our Highlands; In the North Isles of Sanda Westra &c. Many of the Countrey People wear a piece of a Skin, as of a Scale, comonly called a Selch, Calf or the lik. for Shoes, which they fasten to their Feet with stringes or thongs of Leather. Their Houses are in good order, and well furnished, according to their qualities. They generally speak English."[29][note 1]

As part of the agricultural improvement movement of the 19th century the brothers Malcolm and Samuel Laing created a "New Model Farm" near the Loth ferry terminal at the south end of the island. They introduced merino sheep, and the ruins of the steam engine house and the red-brick chimney and boiler house are still visible. Although such innovations brought increased productivity and were widely copied in Orkney they also impoverished the substantial population of landless cottars who were increasingly marginalised.[30][31]

During World War II, the Royal Air Force built a Chain Home radar station at Whale Head near Lop Ness.[32] This necessitated the building of a large camp at Langamay to house the military personnel, which incorporated a cinema.[31]

Sanday also once boasted the most northerly passenger railway in the United Kingdom, a privately owned rideable miniature installation near Braeswick, the Sanday Light Railway.[33]

Start Point Lighthouse

Start Point Lighthouse in 2007 | |

Orkney | |

| |

| Location | Start Point Sanday Orkney Scotland United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 59.277431°N 2.375906°W |

| Year first constructed | 1806 (first) |

| Year first lit | 1870 (current) |

| Automated | 1962 |

| Construction | stone tower |

| Tower shape | cylindrical tower with balcony and lantern |

| Markings / pattern | white and black vertical stripes tower, black lantern, ochre trim |

| Tower height | 25 metres (82 ft) |

| Focal height | 24 metres (79 ft) |

| Light source | solar power |

| Range | 24 nautical miles (44 km; 28 mi) |

| Characteristic | Fl (2) W 20s. |

| Admiralty number | A3718 |

| NGA number | 3276 |

| ARLHS number | SCO-225 |

| Managing agent | Northern Lighthouse Board[34] [35] |

| Heritage | category B listed building |

Start Point lighthouse on Sanday was completed on 2 October 1806 by engineer Thomas Smith (engineer). It was the first Scottish lighthouse to have a clockwork-driven revolving parabolic reflector creating a sweeping beam. The reflector was later replaced by a Fresnel lens. In 1870 the lighthouse was rebuilt. Since 1915, it has been painted by distinctive black and white vertical stripes which are unique in Scotland. The light was automated in 1962 and is powered by a bank of 36 solar panels.[36]

Despite the presence of the lighthouse, HMS Goldfinch was wrecked in fog on Start Point in 1915.[37]

Current island activities

Sanday boasts two golf courses: a 9-hole links course of 2,600 yards run by Sanday Golf Club and the one-hole meadowland "Peedie Golf Course" of 57 yards (52.1 m) (believed to be Scotland's shortest) at West Manse.[38]

In 2004, three wind turbines with an installed capacity of 8.25 Megawatts were erected by Scottish and Southern Energy (SSE) at Spurness.[39][40] Sanday Community Council successfully negotiated a wind farm community fund with SSE which will be benefitting the people of the island for the lifetime of the turbines, anticipated to be 20 to 25 years.[41] By 2012, these wind turbines were replaced by 5 newer ones by Scottish and Southern Energy. This installation also generates income intended to benefit the people in Sanday, on the one hand via grants distributed by the Sanday Community Council and on the other by financing the Sanday Development Trust.

In 1996, the Sanday Development Group was formed to promote tourism. This group became Sanday Development Trust in 2004, which has a vision to:

create an economically prosperous, sustainable community that is connected with the wider world, but remains a safe, clean environment, where we are proud to live, able to work, to bring up and educate our children, to fulfill our own hopes and ambitions, and to grow old gracefully, enjoying a quality of life that is second to none.

Projects include the establishment of a sports hall and youth centre, the creation of a local sound archive, and until February 2020, a Countryside Ranger service.[42]

A district tartan has been designed for Sanday by one of the island's residents, although it has not yet been officially adopted by the island authorities. It represents the sea, the distinctive sandy beaches and green meadows of the island, and the vertical stripes of Start Point lighthouse.[43]

In July 2008 a concert held on the island was the culmination of an innovative musical project. The main aim of project was to set up a music-teacher training programme that would provide additional music tuition in the school and throughout the community.[44]

A shop where islanders can sell craft products has existed since 2016.

Folklore

There is a legend that a Sanday girl was once sold a book called The Book of Black Art by a witch, and that the Devil would claim the soul of anyone who still owned the book at their death. This book was only able to be passed on by selling it. A local clergyman (Matthew Armour) took it of her hands and he managed to get rid of it by means not described in the tradition before his death in 1903.[45] At the ruined Kirk of Lady, near Overbister, are the "Devil's Clawmarks": incised parallel grooves in the parapet of the kirk.[31]

Natural history

| Designations | |

|---|---|

| Official name | East Sanday Coast |

| Designated | 11 August 1997 |

| Reference no. | 917[46] |

Seals and otters can be found in and around Sanday. There are several SSSIs on the island and the marine coast around the east of the island is designated a Special Protection Area due to presence of sand dune and machair habitats, rare outside the Hebrides, as well as extensive intertidal flats and saltmarsh.[47]

People associated with Sanday

- Matthew Armour (1820–1903), born in Paisley, Sanday's radical Free Kirk Minister who lived at The West Manse (formerly the Free Church of Scotland manse) for over half a century

- Stuart Christie (1946-2020), Glasgow Anarchist, who ran the radical publishing house Cienfuegos Press from here during the late 1970s.[48]

- William Towrie Cutt (1898–1981), author born on Sanday, lived in Kettletoft

- Peter Maxwell Davies (1934–2016), former Master of the Queen's Music

- Walter Traill Dennison (1826–1894), Orcadian folklorist born on Sanday at North Myre, living most of his life at West Brough.[49]

- Ivan Drever; born at Whip and grew up at East Thrave

- David Harvey (b. 1948), former Leeds United and Scotland goalkeeper

- Geoffrey Hayes, actor and children's TV presenter, had a holiday cottage here in the early 1980s

- George Faulknor Francis Horwood (1838–1897), Deputy Lieutenant of Orkney (and youngest son of Edward Horwood, of Weston Turville, Buckinghamshire) who lived at Scar House.

- Liam McArthur MSP for Orkney

- John D Mackay (b. 1909), Headmaster of Sanday School from 1946 to 1970

- William Sichel (b. 1953). International ultra distance runner; World No.1 for the Six Day event in 2006; has represented Great Britain eleven times since 1996.

Notes

References

Citations

- Orkney Placenames. Orkneyjar. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- Anderson (1873) p. 176.

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 392

- Area and population ranks: there are c. 300 islands over 20 ha in extent and 93 permanently inhabited islands were listed in the 2011 census.

- Ordnance Survey. OS Maps Online (Map). 1:25,000. Leisure. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- National Records of Scotland (15 August 2013). "Appendix 2: Population and households on Scotland's Inhabited Islands" (PDF). Statistical Bulletin: 2011 Census: First Results on Population and Household Estimates for Scotland Release 1C (Part Two) (PDF) (Report). SG/2013/126. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Pedersen, Roy (January 1992). Orkneyjar ok Katanes (map, Inverness, Nevis Print)

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 334.

- Waugh, Doreen "Orkney Place-names" in Omand (2003) p. 115

- Dorward (1995) p. 42

- "Orkney Placenames: Houses, Farms and Building" Orkneyjar. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- "Orkney Placenames: Natural Elements". Orkneyjar. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- Groome, Frances (1882-84) Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland quoted by Vision of Britain: Otterswick Orkney. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- Steinnes (1959) p. 41

- Keatinge and Dickson (1979) p. 587

- Brown, John Flett "Geology and Landscapes" p. 4 in Omand (2003).

- "The Quoyness Cairn, Sanday". Orkneyjar. Retrieved 19 July 2012.

- Batey, Colleen "Viking and Late Norse Orkney" pp. 57-58 in Omand (2003).

- "Rapid response to storm damaged archaeology". AOC Archaeology Group. Archived from the original on 2008-12-03. Retrieved 2008-11-14.

- "Sanday: Broch of Wasso, Tres Ness". Canmore. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Wickham-Jones (2007) p. 82

- Wickham-Jones (2007) p. 100

- Wickham-Jones (2007) p. 104

- "Sanday, Quoy Banks". Canmore. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Sigurd Towrie. "The Scar Viking Boat Burial". Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- Steinnes (1959) p. 46.

- Stewart, Walter (mid-1640s) "New Choreographic Description of the Orkneys" in Irvine (2006) p. 24. Translated from the original Latin by Ian Cunningham.

- Miscellany of the Abbotsford Club, vol. 1 (Edinburgh, 1837), pp. 150-163.

- Brand, Reverend John (1701) "A Brief Description of Orkney, Zetland, Pightland-Firth & Caithness". Originally printed by George Mossman. Edinburgh. University of Glasgow. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- Thomson, William P. L. "Agricultural Improvement" in Omand (2003) p. 96

- "Archeology and History" Archived 2014-10-28 at the Wayback Machine. Sanday Tourism Association. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- "Sanday, Whale Head Chain Home Radar Station". Scotland's Places. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- Welstead, Julia (4 March 2006). "Do the Locomotion with Charlie". The Scotsman. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Start Point The Lighthouse Directory. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 26 May 2016

- "Start Point". Northern Lighthouse Board. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Start Point Lighthouse". Northern Lighthouse Board. Archived from the original on 2008-12-09. Retrieved 2008-11-14.

- "Remains of HMS Goldfinch". Orkney Image Library. Archived from the original on 2014-01-13. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- "The Islands of Orkney". 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "West Wight Project Environmental Statement: Chapter 1 - Introduction" (PDF). Your Energy Ltd. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-06-02.

- "Chairman's Report" (PDF). Orkney Renewable Energy Forum. 2005. Retrieved 2008-11-14.

- "Various minutes". www.sanday.co.uk. Sanday Community Council. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2008-11-14.

- "Sanday Development Trust". Development Trusts Association Scotland. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-06-02.

- "Sanday Tartan". Scotsheraldry.com. Archived from the original on 2007-10-08. Retrieved 2007-06-02.

- "Island of Sanday hits the right note". Local People Leading. Retrieved 2008-07-19.

- Ash (1973) p. 476

- "East Sanday Coast". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "Sanday site details". JNCC. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- "Pamphlets and Papers: Anarchism". Working Class Movement Library. Archived from the original on 2008-03-05. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

- The Dennison Collection, University of Glasgow, retrieved 15 June 2014

Sources

- General references

- Anderson, Joseph (ed.) (1873) The Orkneyinga Saga. Translated by Jón A. Hjaltalin & Gilbert Goudie. Edinburgh. Edmonston and Douglas. The Internet Archive. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- Ash, Russell (1973). Folklore, Myths and Legends of Britain. Reader's Digest Association Limited. ISBN 9780340165973.

- Dorward, David (1995). Scotland's Place Names. Mercat Press. ISBN 1873644507.

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- Irvine, James M. (ed.) (2006) The Orkneys and Schetland in Blaeu's Atlas Novus of 1654. Ashtead. James M. Irvine. ISBN 0-9544571-2-9.

- Keatinge, T. H. and Dickson J. H. (Mar., 1979) "Mid-Flandrian Changes in Vegetation on Mainland Orkney". New Phytologist. Vol. 82, No. 2, pp. 585–612. Wiley//JSTOR Trust Stable Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- Omand, Donald, ed. (2003). The Orkney Book. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

- Steinnes, Asgaut (April 1959) "The 'Huseby' System in Orkney". The Scottish Historical Review. Vol. 38, No. 125, Part 1 pp. 36–46. Edinburgh University Press/JSTOR. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- Wickham-Jones, Caroline (2007) Orkney: A Historical Guide. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1-84158-596-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sanday. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Sanday. |

- "Sanday". Sanday Tourism Association. Archived from the original on 2008-10-22. Retrieved 2008-11-14.

- "Sanday Community Website". Sanday Development Trust. Retrieved 2008-11-14.

- Northern Lighthouse Board