Colonial Williamsburg

Colonial Williamsburg is a living-history museum and private foundation presenting a part of the historic district in the city of Williamsburg, Virginia, United States.

Williamsburg Historic District/Williamsburg Historical Triangle | |

.jpg) View of the reconstructed Raleigh Tavern on Duke of Gloucester Street | |

| |

| Location | Bounded by Francis, Waller, Nicholson, N. England, Lafayette, and Nassau Sts., Williamsburg, Virginia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°16′16.50″N 76°42′0.00″W |

| Area | 173 acres (70 ha) |

| Built | 1699 |

| Architectural style | Georgian |

| Website | https://www.colonialwilliamsburg.com |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000925[1][2] |

| VLR No. | 137-0050 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHLD | October 9, 1960 |

| Designated VLR | September 9, 1969[3] |

Its 301-acre (122 ha) historic area includes several hundred restored or re-created buildings from the 18th century, when the city was the capital of Colonial Virginia; 17th-century, 19th-century, and Colonial Revival structures; and more recent reconstructions. An interpretation of a colonial American city, the historic area includes three main thoroughfares and their connecting side streets that attempt to suggest the atmosphere and the circumstances of 18th-century Americans. Costumed employees work and dress as people did in the era, sometimes using colonial grammar and diction (although not colonial accents).[4]

In the late 1920s, the restoration and re-creation of colonial Williamsburg was championed as a way to celebrate rebel patriots and the early history of the United States. Proponents included the Reverend Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin and other community leaders; the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities (now called Preservation Virginia), the Colonial Dames, the Daughters of the Confederacy, the Chamber of Commerce, and other organizations; and the wealthy Rockefellers John D. Rockefeller Jr., and his wife, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller.

Colonial Williamsburg is part of the part-historic project, part-tourist attraction Historic Triangle of Virginia, along with Jamestown and Yorktown and the Colonial Parkway. The site was once used for conferences by world leaders and heads of state, including U.S. presidents. It was designated a National Historic Landmark District in 1960.[2]

In June 2019, its sixth president, Mitchell Reiss, announced that he would resign effective October, ending a five-year tenure distinguished by staff turnover, downsizing, and outsourcing.[5]

Overview

Colonial Williamsburg is a historical landmark and a living history museum. Its core runs along Duke of Gloucester Street and the Palace Green that extends north and south perpendicular to it. This area is largely flat, with ravines and streams branching off on the periphery. At the City of Williamsburg's discretion, Duke of Gloucester Street and other historic area thoroughfares are closed to motorized vehicles during the day, in favor of pedestrians, bicyclists, joggers, dog walkers, and animal-drawn vehicles.[6]

Surviving colonial structures have been restored as close as possible to their 18th-century appearance, with traces of later buildings and improvements removed. Many of the missing colonial structures were reconstructed on their original sites beginning in the 1930s. Animals, gardens, and dependencies (such as kitchens, smokehouses, and privies) add to the environment. Some buildings and most gardens are open to tourists, the exceptions being buildings serving as residences for Colonial Williamsburg employees, large donors, the occasional city official, and sometimes College of William & Mary associates.[7]

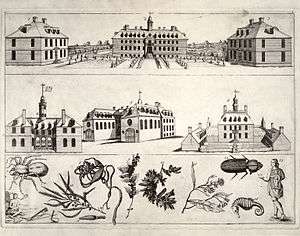

Prominent buildings include the Raleigh Tavern, the Capitol, the Governor's Palace (all reconstructed), as well as the Courthouse, the George Wythe House, the Peyton Randolph House, the Magazine, and independently owned and functioning Bruton Parish Church (all originals). Colonial Williamsburg's portion of the historic area begins east of the College of William & Mary's College Yard.

Four taverns have been reconstructed for use as restaurants and two for inns. There are craftsmen's workshops for period trades, including a printing shop, a shoemaker's, blacksmith's, a cooperage, a cabinetmaker, a gunsmith's, a wigmaker's, and a silversmith's. There are merchants selling tourist souvenirs, books, reproduction toys, pewterware, pottery, scented soap, and tchotchkes. Some houses, including the Peyton Randolph House, the Geddy House, the Wythe House and the Everard House are open to tourists, as are such public buildings as the Courthouse, the Capitol, the Magazine, the Public Hospital, and the Gaol.[8] The Public Gaol served as a jail for the colonists. Former notorious inmates include the pirate Blackbeard's crew who were kept in the 1704 jail while they awaited trial.[9]

Colonial Williamsburg operations extend to Merchants Square, a Colonial Revival commercial area designated a historic district in its own right. Nearby are the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum and DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, operated by Colonial Williamsburg as part of its curatorial efforts.

History of Williamsburg

The Jamestown statehouse, housing Virginia's government at the time, burned down on October 20, 1698. The legislators consequently moved their meetings to the College of William & Mary in Virginia at Middle Plantation, putting an end to Jamestown's 92-year run as Virginia's colonial capital. In 1699, in a graduation exercise, a group of College of William & Mary students delivered addresses endorsing proposals to move the capital to Middle Plantation, ostensibly to escape the malaria – and the mosquitoes which transmit them – of the Jamestown Island site. Interested Middle Plantation landowners donated some of their holdings to advance the plan, and to reap its rewards.[10]

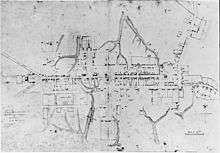

Middle Plantation was renamed Williamsburg by Governor Francis Nicholson, who was first among the proponents of the change, in honor of the Dutch Royal Willem III van Oranje (William of Orange)[11][12]. He was Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Gelderland and Overijssel in the Dutch Republic from 1672 and King of England, Ireland and Scotland from 1689 until his death in 1702 where he was known as king William III of England.[13][14][15] Nicholson said that at Williamsburg "clear and crystal springs burst from the champagne soil". By "champagne," he meant excellent or fertile. Nicholson had the city surveyed and a grid laid out by Theodorick Bland taking into consideration the brick College Building and the decaying Bruton Parish Church building of the day. The grid seems to have obliterated all but the remnants of an earlier plan that laid out the streets in the monogram of William & Mary, a W superimposed on an M. The main street was named Duke of Gloucester after the eldest son of Queen Anne.[16] Nicholson named the street north of it Nicholson Street, for himself, and the one south of it Francis Street.

For eighty-one years of the 18th century, Williamsburg was the center of government, education and culture in the Colony of Virginia. Here, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, James Monroe, James Madison, George Wythe, Peyton Randolph, and others furthered the forms of British government in the Commonwealth of Virginia and later helped adapt its preferred features to the needs of the new United States. During the American Revolutionary War, in 1780, under the leadership of Governor Thomas Jefferson, the government moved to Richmond, on the James River, about 55 miles (89 kilometres) west, to be more central and accessible from western counties, and less susceptible of British attack. There it remains today.[17]

History of Colonial Williamsburg

With the seat of government removed, Williamsburg's businesses foundered or migrated to Richmond, and the city entered a long, slow period of sleepy stagnation and decay. Bypassed by progress, in its isolation the town maintained much of its 18th-century aspect. Captured by General George McClellan in 1862 and garrisoned by the Union for the duration, Williamsburg mostly escaped the ravages of the Civil War, though federal soldiers burned the college and others plundered private homes. The site stood on high ground away from waterways and was not served by the early railroads, whose construction began in the 1830s, and only was reached by the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway in 1881.

Williamsburg relied for jobs on The College of William & Mary, the Courthouse, and the Eastern Lunatic Asylum (now Eastern State Hospital),;[18] it was said that the "500 Crazies" of the asylum supported the "500 Lazies" of the college and town.[18] Colonial-era buildings were by turns modified, modernized, protected, neglected, or destroyed. Development that accompanied construction of a World War I gun cotton plant at nearby Peniman and the coming of the automobile blighted the community, but the town never lost its appeal to tourists. By the early 20th century, many older structures were in poor condition, no longer in use, or were occupied by squatters, but, as Goodwin said, it was the only colonial capital still capable of restoration.

Dr. Goodwin and the Rockefellers

The Reverend Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin became rector of Williamsburg's Bruton Parish Church in 1903 for the first of two periods. Born in 1869 at Richmond to a Confederate veteran and his well-to-do wife, and reared in rural Nelson County at present-day Norwood, Goodwin was educated at Roanoke College, the University of Virginia, the University of Richmond, and the Virginia Theological Seminary. He first visited Williamsburg as a seminarian sent to recruit William & Mary students. Returning as an energetic 34-year-old, he became rector of a Bruton Parish Church riven by factions. He helped harmonize the congregation, and assumed leadership of a flagging campaign to restore the 1711 church building. Goodwin and New York ecclesiastical architect J. Stewart Barney completed the church restoration in time for 1907's 300th anniversary of the founding of America's Anglican (Episcopal) Church at nearby Jamestown, Virginia. Goodwin traveled the East Coast raising money for the project and establishing philanthropic contacts.[19] Among the 1907 anniversary guests was J. Pierpont Morgan, president of the Episcopal church's General Assembly meeting that year in Richmond.

.jpg)

Goodwin accepted a call from wealthy St. Paul's Episcopal Church in Rochester, N.Y. in 1908, and pastored there until his return in 1923 to Williamsburg to become a William & Mary fundraiser and religious studies professor, as well as pastor of Yorktown's Episcopal church and a chapel at Toano. He had maintained his Williamsburg ties, periodically visiting his first wife's and their first son's graves, using William & Mary's library for historical research, and vacationing. What he saw in the deterioration of colonial-era buildings saddened and inspired him. He renewed his associations with the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities—the membership of which included prominent and wealthy Virginians—and helped to protect and repair the town's 18th-century octagonal Powder Horn, a structure now called the Magazine. With other William & Mary professors, he saved the John Blair House from demolition to make way for a gasoline station—and turned it into a faculty club. In 1924, as the college launched a building and fundraising drive, he adopted Barney's proposal for saving other houses in the historic section of the town for use as student and faculty housing. After working for two years to interest such individuals as Henry Ford and such organizations as the Dames of Colonial America to invest in his hopes,[19] Goodwin obtained the at first limited and later complete support (and major financial commitment) of John D. Rockefeller Jr., the wealthy son of the founder of the Standard Oil monopoly. Rockefeller's wife Abby Aldrich Rockefeller was also to play a role. In addition to working as Rockefeller's agent Goodwin returned to the Bruton Parish pulpit in 1926, keeping his college positions.

Rockefeller's first investment in a Williamsburg house had been a contribution to Goodwin's acquisition of the George Wythe House for next-door Bruton Church's parish house. Rockefeller's second and better known was his almost simultaneous authorization of the make-safe purchase of the Ludwell-Paradise house in early 1927. Goodwin persuaded Rockefeller to buy it on behalf of the college for housing in the event Rockefeller should decide to restore the town. Rockefeller had agreed to pay for college restoration plans and drawings. He later considered limiting his restoration involvement to the college and an exhibition enclave. He did not commit to the town's large scale restoration until November 22, 1927—the now-uppercase Restoration's birthday.[19] As Goodwin later put it: “Mr. Rockefeller then stated that he would associate himself with the endeavor to restore colonial Williamsburg!” Until that moment, Rockefeller had always spoken in terms of “if” he would become involved, though all the while acquiring property and proposals.

Concerned that prices might rise if their purposes were known, Rockefeller and Goodwin at first kept their acquisition plans secret, quietly buying houses and lots and taking deeds in blank. Goodwin took Williamsburg attorney Vernon M. Geddy, Sr. into his confidence, without exposing Rockefeller as silent partner. Geddy did much of the title research and legal work related to properties in what was to become the restored area. Geddy later drafted the Virginia corporate papers for the project, filed them with the Virginia State Corporation Commission, and served briefly as the first president of what became the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.[20] That much property changing hands was noticed by the courthouse crowd and by newspaper reporters. After eighteen months of increasingly excited rumors, Goodwin and Rockefeller revealed what had become an open secret — their plans, at county and town meetings on June 11 and 12, 1928.[19] The purpose was to obtain the consent of the citizenry at large and enlist them in the project. No African Americans attended the meetings, or were formally consulted about their town's future. Town and county controlled properties the restoration project required—a new high school and two public greens, among them. The city retained ownership of its streets, an arrangement that forestalled later proposals to raise revenue by closing the historic area to unticketed tourists.[19][21]

Some townspeople had qualms. Major S. D. Freeman, retired Army officer and school board president, said, "We will reap dollars, but will we own our town? Will you not be in the position of a butterfly pinned to a card in a glass cabinet, or like a mummy unearthed in the tomb of Tutankhamun?"[21]

To gain the cooperation of persons reluctant to sell their traditional family homes to the Rockefeller organization, the restoration soon offered holdouts free life tenancies and maintenance in exchange for ownership. Freeman sold his house outright and moved to Virginia's Middle Peninsula.[19]

Restoration and reconstruction

Rockefeller management decided against giving custody of the project to the state-run college—ostensibly to avoid political control by Virginia's Democratic Byrd Machine—but restored the school's Wren Building, Brafferton House and President's House.[19] Colonial Williamsburg pursued a program of partial re-creation of some of the rest of the town. It featured shops, taverns and open-air markets in a colonial style.

The first lead architect in the project was William Graves Perry of Perry, Shaw & Hepburn, with Arthur Shurcliff as the chief landscape architect. Upon consultation by Perry with Fiske Kimball, additional architects were brought in to serve as an Advisory Committee on Architecture intended to review plans and shield the project from criticism.

During the restoration, the project demolished 720 buildings that postdated 1790, many of which dated from the 19th century. Some decrepit 18th-century homes were demolished, some needlessly.[19] The Governor's Palace and the Capitol building were reconstructed on their sites with the aid of period illustrations, written descriptions, early photographs, and informed guesswork. The grounds and gardens were almost all done in the authentic Colonial Revival style.[22]

The Capitol is a 1930s beaux arts approximation of the 1705 building at the east end of the historic area. It was designed by the architects Perry, Shaw & Hepburn, who had it rebuilt as they thought it should have been, not as it was, despite objections and archaeological evidence to the contrary.[19] Its 1705 original, an H-shaped brick statehouse with a double-apsed, oarsmen-circular southern facades, burned in the 1740s, and was replaced by an H-shaped rectangular edifice. The reconstruction is off center, its floorplan is skewed, and its interior is overly elaborate. In the second building, Patrick Henry, protesting against the Stamp Act, first spoke against King George, George Mason introduced the Virginia Bill of Rights, and from it Virginia's government instructed its delegates to the Second Continental Congress to propose national independence. Its likeness only exists in a period woodcut and in architectural renderings considered but shelved by the Restoration. The present building was dedicated with a ceremonial meeting of the Virginia General Assembly on February 24, 1934.[10] Virginia's state legislators have reassembled for a day every other year in the Capitol[10]

Of the approximately 500 buildings reconstructed or restored, 88 are labelled original.[23] They include outbuildings such as smokehouses, privies, sheds. The foundation reconstructed the Capitol and Governor's Palace on their 18th-century foundations and preserved some below-ground 18th-century brickwork, classifying them as reconstructions. It rebuilt William & Mary's Wren Building, which burned four times in 230 years and was much modified, on its original foundations, too, saved some above-ground brickwork, and classified the result as original. At least one historic area house that Colonial Williamsburg took down to its basement and replaced its superstructure is likewise classified among the 88. A building a few lots away, similarly handled, is defined as a reconstruction.

On the western side of the city, beginning in the 1930s, retail shops were grouped under the name Merchants Square to accommodate and mollify displaced local merchants. Increasing rents and tourist-driven businesses eventually drove out all the old-line community enterprises except a dress shop. One of the last to be forced out, a popular-with-locals drugstore complete with lunch counter, was supplanted by Williams Sonoma.

Outlying landscapes and viewsheds

Beginning in the earliest period of the Restoration, Colonial Williamsburg acquired acreage in Williamsburg and the two counties which adjoin it, notably to the north and east of the historic area to preserve natural views and facilitate the experience of as much of the late 18th-century environment as possible. This was described as a "rural, wooded sense of arrival" along corridors to the historic area.[24]

In 2006, announcing a conservation easement on acreage north of the Visitor Center, Colonial Williamsburg President and Chairman Colin G. Campbell said its restrictions protected the view and preserved other features: "This viewshed helps to set the stage for visitors in their journey from modern day life into the 18th-century setting. At the same time, this preserves the natural environment around Queen's Creek and protects a significant archaeological site. It is a tangible and important example of how the Foundation is protecting the vital greenbelt surrounding Colonial Williamsburg’s historic area for future generations".[25]

The entrance roadways to the historic area were planned with care. The Colonial Parkway was planned and is maintained to reduce modern intrusions.

Near the principal planned roadway approach to Colonial Williamsburg, similar design priorities were employed for the relocated U.S. Route 60 near the intersection of Bypass Road and North Henry Street. Prior to the restoration, U.S. Route 60 ran right down Duke of Gloucester Street through town. To shift the traffic away from the historic area, Bypass Road was planned and built through farmland and woods about a mile north of town. Shortly thereafter, when Route 143 was built as the Merrimack Trail (originally designated State Route 168) in the 1930s, the protected vista was extended along Route 132 in York County to the new road, and two new bridges were built across Queen's Creek.

Goodwin, who served as a liaison with the community, as well as with state and local officials, was instrumental in such efforts. Nevertheless, some in the Rockefeller organization, regarding him as meddlesome, gradually pushed Goodwin to the periphery of the Restoration and by the time of his death in 1939 Colonial Williamsburg's administrator, Kenneth Chorley of New York, was indiscreetly at loggerheads with the local reverend. Goodwin's relationship with Rockefeller remained warm, however, and his interest in the project remained keen. Colonial Williamsburg dedicated its headquarters in 1941, naming it The Goodwin Building.

About 30 years later, when Interstate 64 was planned and built in the 1960s and early 1970s, from the designated "Colonial Williamsburg" exit, the additional land along Merrimack Trail to Route 132 was similarly protected from development. Today, visitors encounter no commercial properties before they reach the Visitor's Center.

Not only highway travel was considered. Although Williamsburg's brick Chesapeake and Ohio Railway passenger station was less than 20 years old and one of the newer ones along the rail line, it was replaced with a larger station in Colonial style which was located just out of sight and within walking distance of the historic area.

Further afield was Carter's Grove Plantation. It was begun by a grandson of wealthy planter Robert "King" Carter. For over 200 years, it had gone through a succession of owners and modifications. In the 1960s after the death of its last resident, Ms. Molly McRae, Carter's Grove Plantation came under the control of Winthrop Rockefeller's Sealantic Foundation, which gave it to Colonial Williamsburg as a gift. Archaeologist Ivor Noel Hume discovered in its grounds the remains of 1620s Wolstenholme Towne, a downriver outpost of Jamestown. The Winthrop Rockefeller Archaeology Museum, built just above the site, showcased artifacts from the dig. Colonial Williamsburg operated Carter's Grove until 2003 as a satellite facility of Colonial Williamsburg, with interpretive programs. The property was sold to a dot com millionaire who declared bankruptcy before completing the purchase and the empty facility remained in limbo for more than a decade.[26]

Kingsmill

Between Carter's Grove and the Historic District was the largely vacant Kingsmill tract, as well as a small military outpost of Fort Eustis known as Camp Wallace (CW). In the mid-1960s, CW owned land that extended all the way from the historic district to Skiffe's Creek, at the edge of Newport News near Lee Hall. Distant from the historic area and not along the carefully protected sight paths, it was developed in the early 1970s, under CW Chairman Winthrop Rockefeller.

Rockefeller, a son of Abby and John D. Rockeller Jr., was a frequent visitor and particularly fond of Carter's Grove in the late 1960s. He became aware of some expansion plans elsewhere on the Peninsula of his St. Louis-based neighbor, August Anheuser Busch, Jr., head of Anheuser-Busch. By the time Rockefeller and Busch completed their discussions, the biggest changes in the Williamsburg area were underway since the Restoration began 40 years before. Among the goals were to complement Colonial Williamsburg attractions and enhance the local economy.

The large tract consisting primarily of the Kingsmill land was sold by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation to Anheuser-Busch for planned development. The Anheuser-Busch investment included building a large brewery, the Busch Gardens Williamsburg theme park, the Kingsmill planned resort community, and McLaws Circle, an office park. AB and related entities from that development plan comprise the area's largest employment base, surpassing both Colonial Williamsburg and the local military bases.

Late 20th century

Colonial Williamsburg has become one of the most popular tourist destinations in Virginia. With its historic significance to American democracy, it and the surrounding area was the site of a summit meeting of world leaders, the first World Economic Conference in 1983, and hosted visiting royalty, including King Hussein of Jordan and Emperor Hirohito of Japan. Queen Elizabeth II has paid two royal visits to Williamsburg, most recently in May 2007 during the 400th anniversary of the founding of the nearby Jamestown.

Colonial Williamsburg today

.jpg)

Colonial Williamsburg is an open-air assemblage of buildings populated with historical reenactors (interpreters) whose job it is to explain and demonstrate aspects of daily life in the past. The reenactors work, dress, and talk as they would have in colonial times.

While there are many living history museums (such as Old Sturbridge Village in Massachusetts, Old Salem in Winston-Salem, or Castell Henllys in the UK), Colonial Williamsburg is unusual for having been constructed from a living town whose inhabitants and post-Colonial-era buildings were removed. Also unlike other living history museums, Colonial Williamsburg allows anyone to walk through the historic district free of charge, at any hour of the day. Charges apply only to those visitors who wish to enter the historic buildings to see arts and crafts demonstrations during daylight hours, or attend scheduled outdoor performances such as the Revolutionary City programs.

The Visitor Center near the Colonial Parkway features a short movie, Williamsburg: the Story of a Patriot, which debuted in 1957. Visitors may park at the Visitor's Center, as automobiles are restricted from the restored area. Wheelchair-accessible shuttle bus service is provided to stops around the perimeter of the Historic District of Williamsburg, as well as Jamestown and Yorktown, during the peak summer season.

The costumed interpreters have not always worn Colonial dress. As an experiment in anticipation of the Bicentennial, in summer 1973 the hostesses were dressed in special red, white, and blue polyester knit pantsuits. This confused and disappointed visitors, so the experiment was dropped at the end of summer,[27] and for the Bicentennial, docents wore historical costumes.

Many reenactments by Colonial Williamsburg's historical interpreters wearing period costumes are posted online.[28] In addition to simple period reenactments, Colonial Williamsburg, at various times, features certain themes, including the founding of Williamsburg, occupation by British forces, or visits from Colonial leaders of the day, including General George Washington.

Some of the costumed interpreters work with animals. The Colonial Williamsburg Rare Breed Program helps to preserve and showcase animals that would have been around during the colonial period. John P. Hunter wrote an excellent book on the topic, Link to the Past, Bridge to the Future: Colonial Williamsburg's Animals, which explains the importance of, as well as details how interpreters are a part, of this program.

Colonial Williamsburg is a pet-friendly destination. Leashed pets are permitted in specific outdoor areas and may be taken on shuttle buses, but are not permitted in buildings except the visitor center.[29]

Grand Illumination

The Grand Illumination is an outdoor ceremony and mass celebration involving the simultaneous activation of thousands of Christmas lights each year on the first Sunday of December. The ceremony, Goodwin's idea, began in 1935, loosely based on a colonial (and English) tradition of placing lighted candles in the windows of homes and public buildings to celebrate a special event, such as the winning of a war or the birthday of the reigning monarch. The Grand Illumination also has incorporated extravagant fireworks displays, loosely based on the 18th-century practice of using fireworks to celebrate significant occasions.

Educational outreach

In the 1990s Colonial Williamsburg implemented the Teaching Institute in Early American History, and Electronic Field Trips. Designed for elementary and middle/high school teachers, the institute offers workshops for educators to meet with historians, character interpreters, and to prepare instructional materials for use in the classroom.[30] Electronic Field Trips are a series of multimedia classroom presentations available to schools. Each program is designed around a particular topic in history and includes a lesson plan as well as classroom and online activities. Monthly live broadcasts on local PBS stations allow participating classes to interact with historical interpreters via telephone or internet.[31]

In 2007, Colonial Williamsburg launched iCitizenForum.com. A mix of historical documents and user-generated content such as blogs, videos, and message boards, the site aims to prompt discussion about the roles, rights, and responsibilities of citizens in a democracy. Preservation of the Founding Fathers' ideals in light of recent world events is a special focus of the site.

CW hired former NBC journalist Lloyd Dobyns to produce the early podcasts for the museum. He usually interviewed staff about their specialties.[32] Podcast interviews passed to other hands after his retirement.

Merchandising

Colonial American craft items and souvenirs, some manufactured abroad, are peddled in historic area stores. Many souvenir shops sell such items as floral and herbal soaps, knitted hats, and hand crafted toys made from wood and clay.

Management

Colonial Williamsburg is owned and operated as a living museum by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, the non-profit entity endowed initially by the Rockefeller family and over the years by others, notably Reader's Digest founders Lila and DeWitt Wallace, and Philadelphia publisher Walter Annenberg.

The major goal of the Restoration was to re-create the physical colonial environment and to facilitate education about the origins of the idea of America, which was conceived during the decades before the American Revolution. In this environment, Colonial Williamsburg strives to tell the story of how diverse peoples, having different and sometimes conflicting ambitions, evolved into a society that valued liberty and equality.[33]

Mitchell Reiss, former president of Washington College, is the foundation's current President and CEO. Thomas F. Farrell II is Chairman of the Board of Trustees.

Attendance

Attendance at Colonial Williamsburg peaked in 1985 at 1.1 million visitors.[34] After years of lowered attendance, it began to rebound somewhat with the Jamestown 2007 celebration and the Revolutionary City programs of live, interactive street theater between re-enactors and audience members, which began in 2006.

Since its lowest point in 2004, total attendance has climbed about 10 percent total over the following years, according to a report in July 2008. During 2008, CW's hospitality revenue increase of 15 percent was much stronger than the ticket sale gain of 5 percent, reflecting how the hospitality money is not always coming from CW historic area tourists, according to an official.[35]

The foundation's official attendance figures are best read in context. Until the 1990s they reflected only general admission tickets sold, and that number was sometimes artificially bolstered by internal year-end sales and new year repurchases between the non-profit foundation and its for-profit wholly owned subsidiary hotels. Afterward, the foundation estimated the number of tourists who walked the streets without purchasing a ticket, and added them to attendance figures. In the 2000s, head counts were adjusted to reflect tourists who rode the foundation's buses, who visited its museums, who bought carriage rides, who went to night programs, and the like. These numbers were reported as "turnstile" counts. From old annual reports, it appears general admission ticket sales have never reached one million.

Financial challenges

Persistent operating deficits challenge Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Income comes from attendance and merchandising, but is lost at hospitality properties. Other funds come from investments of the endowments and a fundraising operation that occupies half of the foundation's four-story headquarters. Financially focused efforts in recent years have primarily concentrated on cost containment and stimulating attendance and hospitality revenues. The foundation has also sold some property assets it decided were no longer essential to its core mission, including most of its formerly owned properties on nearby Peacock Hill, which has the local distinction of having formerly been home to Georgia O'Keeffe, Mayor Polly Stryker, and Dr. Donald W. Davis, founder of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science.

In 2017, due to losses, Colonial Williamsburg President Mitchell Reis outsourced management of commercial operations of their hotels, 19 retail stores, and three golf courses.[36]

Land divestment

In 2003, as CW attendance and operating revenues continued to drop, Carter's Grove was closed to the public while its mission and role in CW's programs were redefined. After the sale, officials belatedly determined Carters Grove was paying for itself, one of the bright spots in its troubled balance sheet. Later in 2003, Hurricane Isabel seriously damaged Carter's Grove Country Road, which had linked the estate to the historic area, a distance of 8 miles (13 km), bypassing commercial and public roadways. Colonial Williamsburg shifted some of the interpretive programs to locations contiguous to the historic area in Williamsburg, including the ersatz farm Great Hopes Plantation next to its Visitor Center.

The foundation announced in late 2006 that Carter's Grove would be sold under restrictive conditions. In a front-page article December 31, The New York Times reported that the foundation, struggling because of dwindling attendance and insufficient endowment for upkeep, would be offering the Carter's Grove mansion and grounds for sale to a private purchaser, possibly as soon as January 2007. The foundation justified the sale, in part, by saying it wanted to concentrate on its 18th-century core—as opposed to such attractions as the reconstruction of a 17th-century village on the site—a position at odds with its later, and subsequently undone, decision to assume management of 17th-century historic Jamestowne. The Times said that the dilemma of historic museums and houses is that there are too many of them, upkeep is too expensive, and fewer people are visiting them.[34]

In December 2007, the Georgian-style mansion and 476 acres (193 ha) were acquired for $15.3 million by CNET founder Halsey Minor, whose announced plans to use the property as a private residence and a center for a thoroughbred horse breeding program. The conservation easement on the mansion and 400 of the 476 acres (193 ha) is co-held by the Virginia Outdoors Foundation and the Virginia Department of Historic Resources.[37][38] Some local residents lamented CW's decision to sell Carter's Grove; others stated relief that it would remain largely intact, no small matter in one of the fastest developing counties in Virginia.[38] There was general agreement, however, that the transaction was a disaster for the foundation's management and reputation. In 2011, Halsey Minor stopped making payments, and was foreclosed on by CW after a lengthy legal battle and some deterioration of the house and grounds. In 2014, CW repurchased Carter's Grove from the bankruptcy court, and sold it to a new private investor.

In addition to the large sale of surplus land of the old Kingsmill plantation to Anheuser Busch in the 1970s and the more recent sale of Carter's Grove, the foundation has also sold outlying tracts of land not considered fundamental to its mission.

One of these is a 360-acre (150 ha) tract along historic Quarterpath Road north of State Route 199 and south of U.S. Route 60 east of the historic area. In 2005, it was the City of Williamsburg's largest undeveloped tract under single ownership".[39] Observers have noted that, while most of the Quarterpath land will be developed, the previously vacant land will include park and recreational facilities, and Redoubt Park, dedicated to preserving some of the battlegrounds from the Battle of Williamsburg which occurred on May 5, 1862 during the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War.[40]

A portion of the 437-acre (177 ha) Carr's Hill Tract in York County, north and west of Bypass Road and State Route 132, was also sold. Developments thereon were restricted under the terms of sale so as to not negatively impact the vista available to motorists approaching Colonial Williamsburg. In February, 2007, a developer announced that 313 homes were planned to be built on 65 acres (26 ha) of the historic tract's 437 acres (177 ha). CW had earlier announced that it had donated three conservation easements to the Williamsburg Land Conservancy on 230 acres (93 ha) of the Carr's Hill tract land west of Route 132 in York County.[25]

Transportation

The closest commercial airport is Newport News/Williamsburg International Airport 25–30 minutes driving distance away. Williamsburg is midway between two larger commercial airports, Richmond International Airport and Norfolk International Airport, each about an hour's distance away.

Amtrak offers a passenger rail service stop at Williamsburg, as does Greyhound and Carolina Trailways with intercity buses.

Williamsburg is adjacent to east–west Interstate 64 and the parallel U.S. Route 60 passes through the city. A third road, State Route 143, also extends east to Newport News and Hampton, ending at Fort Monroe. From Richmond, Interstate 295, and other points west, many visitors approach via State Route 5, a scenic byway which passes many of the James River Plantations, or from the south via State Route 10, State Route 31 and the Jamestown Ferry. The Virginia Capital Trail is available for bicycles and pedestrians along the Colonial Parkway and Virginia Route 5.

Williamsburg offers good non-automobile driving alternatives for visitors. The area has both a central intermodal transportation center and Williamsburg Area Transit Authority (WATA), a public transit bus system which operates a network of local routes. The community's public bus system, has its central hub at the transportation center. Color-coded routes, with buses accessible to disabled persons, serve hotels and motels, restaurants, stores, and non-Colonial Williamsburg attractions.

Colonial Williamsburg operates its own fleet of buses with stops close to attractions in the historic area, although no motor vehicles operate during the day on Duke of Gloucester Street (to maintain the colonial-era atmosphere). At night, all the historic area streets are open to automobiles.

Criticism and controversy

The 1920s and 1930s

Some residents of Williamsburg, including Major S.D. Freeman and Cara Armistead, questioned the 1928 transfer of public lands (as compared to private properties). In January 1932, the large marble Confederate Civil War monument was removed from Palace Green, where it had stood since 1908, and placed in the Cedar Grove Cemetery, on the outskirts of town. Some citizens who supported the Colonial reconstruction felt this was too much. The case went to court, and eventually the monument was moved to a new site east of the then-new courthouse.[21] Today, the memorial rests in Bicentennial Park, just outside the Historic Area.

Issues of "accuracy" and "authenticity"

The approach to restoration and preservation taken by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation has long been subject to criticism.

Goodwin was troubled by what he perceived as encroaching commercialization. Among his parting words of advice to Colonial Williamsburg's management were: "If there is one firm guiding and restraining word which should be passed on to those who will be responsible for the restoration in the future, that one word is integrity. A departure from truth here and there will inevitably produce a cumulative deterioration of authenticity and consequent loss of public confidence. Loyalty demands that this principle of integrity be adhered to".[19]

One of the foundation's in-house publications concedes that "Colonial Williamsburg bears the burden of criticism that the restored town appears too neat and clean, too 'spick-and-span', and too manicured to be believable".[22] Ada Louise Huxtable, an architecture critic, wrote in 1965: "Williamsburg is an extraordinary, conscientious and expensive exercise in historical playacting in which real and imitation treasures and modern copies are carelessly confused in everyone's mind. Partly because it is so well done, the end effect has been to devalue authenticity and denigrate the genuine heritage of less picturesque periods to which an era and a people gave life".[41]

All of the restored houses were improved with electricity, plumbing, and heating by 19th- and 20th-century residents and later by Colonial Williamsburg. They have also been furnished with stoves, air conditioners, refrigerators, and bathrooms by today's residents or the foundation. Plaster, woodwork, flooring, siding and roofs were replaced.

In 1997, anthropologists Eric Gable and Richard Handler discussed Colonial Williamsburg as an attraction which catered to America's upper/middle to high-level affluent socioeconomic classes. Their report mentions instances where some of Colonial Williamsburg's employees often straddle expectations of maintaining authenticity of the museum's programs while still in-authentically creating products to sell in the museum's gift shops.[42] An even harsher interpretation is that of University of Virginia Professor of Architectural History Richard Guy Wilson, author of Buildings of Virginia: Tidewater and Piedmont, who described Colonial Williamsburg as "a superb example of an American suburb of the 1930s, with its in-authentically tree-lined streets of Colonial Revival houses and segregated commerce".[43] All of these reproaches have led many critics to label Colonial Williamsburg and its Foundation a "Republican Disneyland".[44]

Among the answers to these criticisms is that "Colonial Williamsburg's Historic Area is a compromise between historical authenticity and common sense, between brutal realism and gentle ambiance, between being a moment in time in the eighteenth century and being nearly three hundred years old".[45] Critics assert that setting "historical authenticity" against "common sense" is a false dichotomy and that commercial and proprietary factors are what are really at issue. Of course archaeological and historical research is an ongoing process at Colonial Williamsburg, and as new information surfaces, reconsideration is often prompted and changes made accordingly.

In March 2016, the foundation's new president and chief executive officer, Mitchell Reiss, told the Richmond Times-Dispatch that Colonial Williamsburg aimed to be "accurate-ish."

At Appalachian State University a graduate level class focuses on the preservation and restoration of Colonial Williamsburg as part of its Public History program.

African Americans

Colonial Williamsburg has been criticized for neglecting the role of free African-Americans in Colonial life, in addition to those who were slaves. When it first opened in the 1930s, Colonial Williamsburg had segregated dormitories for its reenactors. African Americans filled historical roles as servants, rather than free people as in the present day. In a segregated state, Colonial Williamsburg allowed the entry of blacks, but Williamsburg-area hotels denied them accommodation, and state law forbade blacks from eating with whites in such public facilities as the restored taverns and from shopping in nearby stores.[46] In the 1950s, African Americans were only allowed to visit Colonial Williamsburg one day a week until after the U.S. Supreme Court's landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954 began dismantling segregation laws and practices.

Colonial Williamsburg offered some of the earlier public accommodations on an integrated basis. In the 1970s, in reaction to increasing scorn of its one-sided portrayal of colonial life, Colonial Williamsburg increased its number of African-American interpreters who played slaves. This was parodied by a sketch that aired on Saturday Night Live, which showed a reenactor abusing his accuracy by being racist to employees.[47] In 1994 it added slave auctions and slave marriages; the NAACP and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference later protested.[48] In 1981 Colonial Williamsburg added a program to explain slavery and its role in Colonial America, but this "Other Half Tour," which is composed by the Foundation's African American and Interpretation Programs Department (AAIP), provides a different form of historical interpretation than does its counterpart tour, "The Patriots' Tour," thus creating a marked dichotomy between how visitors are expected to interpret history at the museum.[49]

In recent years Colonial Williamsburg has expanded its portrayal of 18th-century African Americans to include free blacks as well as slaves. Examples of these expanded portrayals in the Revolutionary City program include Gowan Pamphlet, a former slave who became a free landowner and Baptist minister, Edith Cumbo, a free black woman, Matthew Ashby, a free black man who eventually purchased the freedom of his family, and a number of other enslaved men and women who were part of the Williamsburg community during the revolutionary period. A re-created Great Hopes Plantation represents a middling plantation, not one owned by the wealthy, in which working-class farmers worked alongside their slaves. Their lives were more typical of colonial Virginians in general than the lives of the wealthier planters, their families and slaves.[50]

See also

- Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum

- DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum

- William Hunter (publisher)

- Norborne Berkeley, 4th Baron Botetourt

- William Parks (publisher)

- Potemkin village

- Joseph Royle (publisher)

- St. George Tucker House

- Tayloe House (Williamsburg, Virginia)

- Christiana Burdett Campbell, namesake of Christiana Campbell's Tavern

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Virginia

- National Register of Historic Places in Williamsburg, Virginia

- Plimoth Plantation

- Westville (Georgia)

- Old Sturbridge Village

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- "Colonial Williamsburg". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 2012-10-06. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- Associated Press, "Next Williamsburg visit could include an 18th-century coffeehouse experience," Richmond Times-Dispatch, Nov. 10, 2009, Richmond, VA (http://www2.timesdispatch.com/business/2009/nov/10/b-togo10_20091109-220006-ar-27743/%5B%5D).

- Jacobs, Jack (18 June 2019). "Colonial Williamsburg president Mitchell Reiss to step down". The Virginia Gazette. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- "Duke of Gloucester Street: Williamsburg, Virginia". Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- Kennicott, Philip, "Brewing new sense of Colonial relevance; Coffeehouse project is steeped in Williamsburg's shift to modern storytelling," The Washington Post, Nov. 19, 2009, Washington, D.C.

- "Colonial Williamsburg's Historic Area". Retrieved 2019-08-12.

- "Public Gaol and Wythe House". Colonial Ghosts. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

- Capitol.

- Willem III van Oranje

- nl:Willem III van Oranje

- William III of England

- "Stadhouder en koning van Engeland Willem III - Historisch Nieuwsblad - Historisch Nieuwsblad". Historischnieuwsblad.nl. 1970-01-01. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- Lilian Visser (2019-08-30). "Koning-stadhouder Willem III van Oranje". Historiek.net. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- "John D. Rockefeller Jr. and the Restoration of Colonial Williamsburg". Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- "April dates in Virginia history Archived 2012-03-01 at the Wayback Machine". Virginia Historical Society Archived 2018-03-31 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on July 11, 2007.

- "500 Lazies and 500 Crazies: Williamsburg Before the Restoration" Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, Crossroads: American Studies, University of Virginia, Retrieved on September 6, 2010.

- Montgomery 1998.

- "GFHlawoffice.com". Archived from the original on 12 September 2009. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- "WPA_Guide: Colonial Williamsburg: The Corporate Town-Reactions". Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- Brinkley & Chappell 1995, p. 3.

- Colihan, Jane (March 2003). "Williamsburg by Ear Archived 2010-10-19 at the Wayback Machine" American Heritage. Retrieved 7-29-2010.

- CW Easement to Preserve 230 Acre Tract: The Williamsburg Land Conservancy Deal Removes Some Development Rights to Carr's Hill.

- "News Releases". Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- "Colonial Williamsburg sells Carter's Grove Plantation after bankruptcy". Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- "Dressing for the Occasion". Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- "Colonial Williamsburg". YouTube. 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- "Colonial Williamsburg, Know Before You Go". colonialwilliamsburg.com. Retrieved 2019-07-25.

- "Teacher Institute in Early American History". Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- "Electronic Field Trips". Archived from the original on 2007-12-30. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

- "Colonial Williamsburg podcasts with Lloyd Dobyns". Archived from the original on 2007-01-07. Retrieved 2007-01-21.

- "Mission of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation". Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- Tracie Rozhon, "Homes Sell, and History Goes Private", The New York Times, Sunday, December 31, 2006, Section 1, page 1.

- "Can history beat failing economy? - dailypress.com". Archived from the original on 2008-09-06. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- "Colonial Williamsburg to outsource operations, announces layoffs". Williamsburg Yorktown Daily. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- .Carter's Grove mansion sells for $15.3 million | HamptonRoads.com | PilotOnline.com

- Carter's Grove sold for $15.3 million - dailypress.com

- 3 Quarter time - VAGazette.com

- VAgazette.com Archived 2008-06-13 at the Wayback Machine

- "Metropolis Magazine - Jan 1998". Archived from the original on 2006-12-11. Retrieved 2006-12-01.

- Handler & Gable 1997, pp. 93-95.

- "error-404". Archived from the original on 2017-01-06. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- Van West, Carroll and Mary Hoffschwelle. "’Slumbering on Its Old Foundations’: Interpretation at Colonial Williamsburg". South Atlantic Quarterly 83 (September 1984): 157-159.

- Brinkley & Chappell 1995, p. 4.

- "The Shrine of the 1930's". Archived from the original on 16 September 2007. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- "Colonial Williamsburg". Saturday Night Live - Season 32, Episode 3 - 10/21/06. NBC. Archived from the original on 2015-03-02. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- Tamara Jones, "Living History or Undying Racism?" Washington Post, October 11, 1994.

- Handler & Gable 1997, p. 59.

- "Great Hopes Plantation". Retrieved 3 November 2016.

Sources

- Brinkley, Kent; Chappell, Gordon W. (1995). The Gardens of Colonial Williamsburg. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. ISBN 978-0879351588.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Capitol". The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Handler, Richard; Gable, Eric (1997). The New History in an Old Museum: Creating the Past at Colonial Williamsburg. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-1974-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Montgomery, Dennis (1998). A Link Among the Days, The Life and Times of the Rev. Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin, the Father of Colonial Williamsburg. Dietz Press. ISBN 0875170943.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Montgomery, Dennis, "A Link Among the Days, The Life and Times of the Reverend Doctor W. A. R. Goodwin, the Father of Colonial Williamsburg," Dietz Press, Richmond. 1998. ISBN 0-87517-094-3

- Carson, Cary and Lounsbury, Carl R. The Chesapeake House: Architectural Investigation by Colonial Williamsburg. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

- Coffman, Suzanne E. and Olmert, Michael, Official Guide to Colonial Williamsburg, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia 2000. ISBN 0-87935-184-5

- Gonzales, Donald J., Chronicled by. The Rockefellers at Williamsburg: Backstage with the Founders, Restorers and World-Renowned Guests. McLean, Virginia: EPM Publications, Inc., 1991.

- Huxtable, Ada Louise, The Unreal America: Architecture and Illusion, The New Press, New York 1997. ISBN 1-56584-055-0

- Scott Magelssen, Living History Museums: Undoing History Through Performance, Scarecrow Press, 2007. ISBN 0-8108-5865-7

External links

- Colonial Williamsburg in 1936

- Official website

- Historic Colonial Times from the Colonial Williamsburg

- (an article from Colonial Williamsburg Journal, 2004)

- "The City That Grew Backwards" Popular Mechanics, July 1935 pp.88-90

- Colonial Williamsburg at the Wayback Machine (archived May 17, 2001)

- Old Courthouse, Courthouse Green, Williamsburg, Williamsburg, VA: 1 photo and 11 measured drawings at Historic American Buildings Survey

- Magazine, 103 Duke of Gloucester Street, Williamsburg, Williamsburg, VA: 1 photo and 7 measured drawings at Historic American Buildings Survey

- Governor's Palace (reconstructed), Palace Green, Williamsburg, Williamsburg, VA: 4 photos and 5 data pages at Historic American Buildings Survey