Balinese architecture

Balinese architecture is a vernacular architecture tradition of Balinese people that inhabits volcanic island of Bali, Indonesia. The Balinese architecture is a centuries-old architectural tradition influenced by Balinese culture developed from Hindu influences through ancient Javanese intermediary, as well as pre-Hindu elements of native Balinese architecture.[1]

.jpg)

Today, contemporary Balinese style is known as one of the most popular Asian tropical architecture,[2] due largely to the growth of the tourism industry in Bali that has created demand for Balinese-style houses, cottages, villas and hotels. Contemporary Balinese architecture combines traditional aesthetic principles, island's abundance of natural materials, famous artistry and craftmanship of its people, as well as international architecture influences, new techniques and trends.

Materials

_voorstellend_een_episode_uit_een_hindoe%C3%AFstisch_heldendicht_TMnr_60025463.jpg)

Traditional Balinese buildings seek to be in harmony with the environment. Traditional Balinese houses are built almost entirely of organic materials.[2] They use natural materials such as thatch roofing, bamboo poles, woven bamboo, coconut wood, teak wood, brick and stone. The thatched roof usually uses ijuk (black aren fibers), dried coconut or rumbia leaves, or sirap (hard wood shingles arranged like tiles) roof.[3] Stones and red bricks are usually used as foundation and walls, while sandstone and andesite stone are usually carved as ornamentation.

Balinese people are known for their artistry. They have developed a sophisticated sculpting tradition that manifests in architecture rich with ornamentation and interior decoration. Balinese temples and palaces are exquisitely decorated with rich ornamentations, both wooden and stone sculpting, which usually depict floral patterns. Balinese sculpture often served as gate guardians as twin dvarapalas flanking entrances. The gates itself are richly decorated with kala's head, floral ornaments, and vajra or ratna pinnacles. Other types of sculpture are often served as ornamentation, such as goddess or dragon waterspouts in bathing places.

Philosophy

Balinese architecture is developed from Balinese ways of life, their spatial organization, their communal-based social relationships, as well as philosophy and spirituality influenced its design; much owed to Balinese Hinduism. The common theme often occur in Balinese design is the tripartite divisions.[2]

Traditional Balinese architecture, adheres to strict and sacred laws of building, allowing much open space and consisting of a spacious courtyard with many small pavilions, ringed by wall to keep out evil spirits and decorated with guardian statues.[4] The philosophical and conceptual basis underlining development of Balinese traditional architecture includes several concepts such as:[5]

- Tri Hita Karana: the concept of harmony and balance consists of three elements; atma (human), angga (nature), and khaya (gods). Tri Hita Karana prescribe three ways that a human beings must strive to nurture harmonious relationship with; fellow human beings, nature, and God.

- Tri Mandala: the rules of space division and zoning. Tri Mandala is spatial concept describing three parts of realms, from Nista Mandala — the outer and lower mundane less-sacred realm, Madya Mandala — the intermediate middle realm, to Utama Mandala — the inner and higher most important sacred realm.

- Sanga Mandala: also the rules of space division and zoning. The Sanga Mandala is the spatial concept concerning with directions that divide an area into nine parts according to eight main cardinal directions and central (zenith). These nine cardinal directions is connected to Hindu concept of Guardians of the directions, Dewata Nawa Sanga or nine guardian gods of directions that appear in Majapahit emblem Surya Majapahit. They are; Center: Shiva, East: Isvara, West: Mahadeva, North: Vishnu, South: Brahma, Northeast: Sambhu, Northwest: Sangkara, Southeast: Mahesora, and Southwest: Rudra.

- Tri Angga: the conception of hierarchy from microcosm, middle realm, and macrocosm. It is also connected to the next concept tri loka.[2]

- Tri Loka: also the conception of hierarchy between three realms bhur (Sanskrit:bhurloka) lower realm of animals and demons, bhuwah (Sanskrit:bhuvarloka) middle realm of human, and swah (Sanskrit:svarloka) upper realms of gods and deities.

- Asta Kosala Kosali: the eight guidelines for architectural designs, which includes the shapes of niyasa (symbols) in pelinggih (shrine), pepalih (stages), its measurement units, shapes and size, also dictate appropriate decorations.

- Arga Segara or Kaja Kelod: the sacred axis between. arga or kaja (mountain) and segara or kelod (sea). Mountain region are considered as parahyangan, the abode of hyang or gods, middle plain in between are the realm of human, and the sea as the realm of sea monster and demons.

Other than artistic and technical mastery, all Balinese architect (Balinese:Undagi) are required to master these Balinese philosophical concepts concerning form, architecture, and spatial organization.

Religious architecture

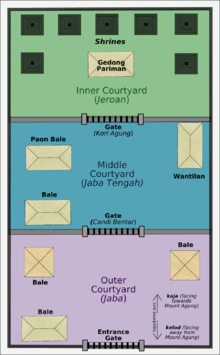

Balinese temple or pura (Sanskrit for:"walled city") are designed as an open air place of worship within enclosed walls, connected with a series of intricately decorated gates between its compounds. This walled compounds contains several shrines, meru (towers), and bale (pavilions). The design, plan and layout of the pura follows the Tri Mandala concept of Balinese space allocation.[6] The three mandala zones are Nista Mandala (jaba pisan): the outer zone, Madya Mandala (jaba tengah): the middle zone, and Utama Mandala (jero): the holiest and the most sacred zone.

Balinese temple usually contains a padmasana, the towering lotus throne of the highest god, Acintya (Sang Hyang Widhi Wasa in modern Balinese), the pelinggih meru, (a multiple roofed tower similar in design to the Nepali or Japanese pagoda), and various pavilions, including bale pawedan (vedic chanting pavilion), bale piyasan, bale pepelik (offering pavilion), bale panggungan, bale murda, and gedong penyimpenan (storehouse of the temple's relics).

Domestic architecture

Unlike European architecture, Balinese houses and puri (palaces) are not created as a single huge building, but rather a collection of numerous structures within walled enclosure each with a special functions; such as front open pavilion to receive guests, main bedroom, other bedrooms, pelinggihan or pemrajan is a small family shrine, living areas and kitchen. Kitchen and living areas that hold everyday mundane activities are usually separated from family shrine. Most of these pavilions are created in Balinese balé architecture, a thatched roof structure with or without walls similar to Javanese pendopo. The walled enclosure are connected with series of gates. Balinese architecture recognize two types of gates, the candi bentar split gate, and paduraksa or kori roofed gates.

In Balinese palace architecture, its size are bigger, the ornamentation is richer and more elaborately decorated than common Balinese houses. The balé gede is a pavilion of 12 columns, where the oldest male of the family sleeps, while wantilan is a rectangular wall-less public building, where people convene or hold cockfighting. The bale kulkul is an elevated towering structure, topped with small pavilion where the kulkul (Balinese slit drum) is placed. The kulkul would be sounded as the alarm during village, city or palace emergency, or a sign to congregate villagers. In Balinese villages there is a bale banjar, a communal public building where the villagers congregate.

.jpg)

Landscape architecture

Balinese gardens are usually created in a natural tropical style filled with tropical decorative plants in harmony with the environment. The garden is usually designed according to natural topography and hardly altered from its natural state. Some water gardens however are laid out in a formal design, with ponds and fountains, such as Taman Ayun and Tirta Gangga water garden. Bale kambang, which literary means "floating pavilion", is a pavilion surrounded with ponds usually filled with water lilies. Petirtaan is a bathing place, consisting of a series of ponds and fountains used for recreation as well as for ritual purification bathing. The examples of petirtaan is bathing structure in Goa Gajah and Tirta Empul.

Elements of Balinese architecture

Candi bentar split gate as the entrance from outer realm.

Candi bentar split gate as the entrance from outer realm. Bale kulkul, a slit drum tower.

Bale kulkul, a slit drum tower. Guardian statues held symbolic meanings also part of decoration in Balinese architecture.

Guardian statues held symbolic meanings also part of decoration in Balinese architecture. Roofed kori agung gate at the Bali Pavilion of Taman Mini Indonesia Indah.

Roofed kori agung gate at the Bali Pavilion of Taman Mini Indonesia Indah. Kala's face as portal guardian and decoration that also contain symbolic meanings.

Kala's face as portal guardian and decoration that also contain symbolic meanings. The pagoda-like multi-tiered roof Meru towers, a typical aspect in Pura.

The pagoda-like multi-tiered roof Meru towers, a typical aspect in Pura. Pelinggih shrines dedicated to certain gods.

Pelinggih shrines dedicated to certain gods.- Stana shrines dedicated to Hindu god Ganesha.

Sanggah kemulan, pemrajan or merajan, small familial house shrines to honor the households' ancestor.

Sanggah kemulan, pemrajan or merajan, small familial house shrines to honor the households' ancestor.- Padmasana, the towering throne of Sang Hyang Widhi Wasa as the focus of worship.

A temple building with multi-tiered roof.

A temple building with multi-tiered roof. A gold-colored roof pinnacle and thatched roof made of black ijuk fibers.

A gold-colored roof pinnacle and thatched roof made of black ijuk fibers. Meticulously carved column, beam and ceiling as the decoration.

Meticulously carved column, beam and ceiling as the decoration. Winged lion as a decoration of the roof interior.

Winged lion as a decoration of the roof interior.- Bale gong, a gamelan pavilion in Balinese temple compound.

Fountain waterspout statues in Goa Gajah sacred bathing pool.

Fountain waterspout statues in Goa Gajah sacred bathing pool..jpg) Lotus pond as part of Balinese landscape architecture.

Lotus pond as part of Balinese landscape architecture. Bale kambang, floating pavilion in Balinese garden.

Bale kambang, floating pavilion in Balinese garden.- Bale bengong, garden contemplating pavilion.

Bale wantilan, a cock-fighting pavilion, an integral part of a temple.

Bale wantilan, a cock-fighting pavilion, an integral part of a temple.- Tirta Empul sacred bathing place.

Indonesia Museum in TMII built in Balinese architecture

Indonesia Museum in TMII built in Balinese architecture

Modern Balinese architecture

The prominence of Bali as a popular island resort with cultural significance has stimulated the demand of modern Balinese architecture applied for tourism-related buildings. Numbers of hotels, villas, cottages, restaurants, shops, museums and airports have incorporated Balinese themes, style and design in their architecture.

See also

- Bali Aga architecture

- Pura Besakih

- Candi

Notes

- "Architecture in Bali". Bali Paradise online. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- Davidson, Julian. Balinese Architecture. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462914227. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- Peter J. M. Nas (2003). The Indonesian Town Revisited, Volume 1 of Southeast Asian dynamics. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 215. ISBN 9783825860387.

- "Balinese Architecture". Ubud Now and Then.

- "Master Program in Architecture and Short Course on Balinese Traditional Architecture". www.unud.ac.id. University of Udayana, Bali. Archived from the original on December 11, 2013. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- "Traditional Balinese Architecture". School of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, Udayana University. Retrieved 2010-07-20.

References

- Julian Davison, Nengah Enu, Luca Invernizzi Tettoni, Bruce Granquist, Introduction to Balinese Architecture, Periplus Asian Architecture Series, 2003, ISBN 0-7946-0071-9