Musaeum

The Musaeum or Mouseion at Alexandria (Ancient Greek: Μουσεῖον τῆς Ἀλεξανδρείας), which included the famous Library of Alexandria,[1] was an institution said to have been founded by Ptolemy I Soter. This original Musaeum ("Institution of the Muses") was the home of music or poetry, a philosophical school and library such as Plato's Academy, and also a storehouse of texts. It did not have a collection of works of art, rather it was an institution that brought together some of the best scholars of the Hellenistic world, analogous to a modern university. This original Musaeum was the source for the modern usage of the word museum.

History

The Musaeum was an institution founded, according to Johannes Tzetzes, by Ptolemy I Soter (c. 367 BC – c. 283 BC) at Alexandria. It is perhaps more likely that Ptolemy II Philadelphus (309–246 BC) was the true founder.[2] The Mouseion remained supported by the patronage of the royal family of the Ptolemies. Such a Greek Mouseion was the home of music or poetry, a philosophical school and library such as Plato's Academy, also a storehouse of texts.[3] Mouseion, connoting an assemblage gathered together under the protection of the Muses, was the title given to a collection of stories about the esteemed writers of the past assembled by Alcidamas, an Athenian sophist of the fourth century BC.

Though the Musaeum at Alexandria did not have a collection of sculpture and painting presented as works of art,[4] as was assembled by the Ptolemies' rival Attalus at the Library of Pergamum, it did have a room devoted to the study of anatomy and an installation for astronomical observations. Rather than simply a museum in the sense that has developed since the Renaissance, it was an institution that brought together some of the best scholars of the Hellenistic world, as Germain Bazin compared it, "analogous to the modern Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton or to the Collège de France in Paris."[5]

More than 1,000 scholars lived in the Mouseion at a given time. Staff members and scholars were salaried by the Mouseion and paid no taxes. They also received free meals, free room and board, and free servants. The Mouseion was administered by a priest appointed by the Pharaoh.[6]

The Mouseion's scholars conducted scientific research, published, lectured, and collected as much literature as possible from the known world. In addition to Greek works, foreign texts were translated from Assyrian, Persian, Jewish, Indian languages, and other sources.[6] The edited versions of the Greek literary canon that we know today, from Homer and Hesiod forward, exist in editions that were collated and corrected by the scholars assembled in the Musaeum at Alexandria.

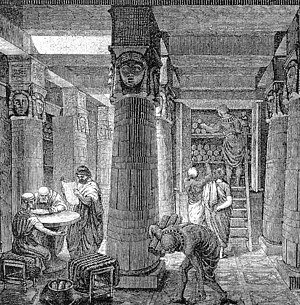

Appearance

The Greek geographer Strabo described the Musaeum and Library as richly decorated edifices in a campus of buildings and gardens.

The Mouseion is also part of the palaces, possessing a peripatos[7] and exedra[8] and large oikos, in which the common table[9] of the philologoi, men who are members of the Mouseion, is located. This synodos has property in common and a priest in charge of the Mouseion, formerly appointed by the kings, but now by Caesar. —Strabo [10]

The Mouseion featured a roofed walkway, an arcade of seats, and a communal dining room where scholars routinely ate and shared ideas. The building was filled with private study rooms, residential quarters, lecture halls, and theaters.[6]

Notable scholars

The following scholars are known to have studied, written, or performed their experiments at the Musaeum of Alexandria.[11]

- Archimedes – father of engineering

- Aristarchus of Samos – proposed the first heliocentric system of the universe

- Callimachus – a noted poet, critic and scholar

- Erasistratus – physician and co-founder of the Academy of Medicine in Alexandria along with Herophilus

- Eratosthenes – argued for a spherical earth and calculated its circumference to near-accuracy

- Euclid – father of geometry

- Herophilus – notable physician and founder of the scientific method

- Hipparchus – founder of trigonometry

- Pappus – mathematician

- Hero – father of mechanics

Decline

The classic period of the Musaeum did not survive the purge and expulsion of most of the intellectuals attached to it in 145 BC, when Aristarchus of Samothrace resigned his position; at any rate, the sources that best describe the Musaeum and library, Johannes Tzetzes and others, all Byzantine and late, do not mention any further directors.[12] The Musaeum continued as an institution in the Roman period when Strabo gave his description of it, and according to Suetonius,[13] the emperor Claudius added an additional building.[14] Under the emperors, membership of the Musaeum was awarded to prominent scholars and statesmen, often as a reward to supporters of the emperor.[15] Emperor Caracalla suppressed the Musaeum in 216,[16] perhaps as a temporary measure.[14] By this time, the center of learning in Alexandria had already moved to the Serapeum.[16]

Destruction

The last known references to Musaeum membership occur in the 260s.[17] The Bruchion, the section of Alexandria that included the Musaeum, was probably destroyed by fire on the orders of Emperor Aurelian in 272, although we do not know for sure whether it still existed in 272, the area having already been set ablaze during the occupation by Julius Caesar. Scattered references in later sources suggest that a Musaeum was reestablished in the 4th century on a different site, but little is known about this later organisation and it is unlikely to have had the resources of its predecessor.[17] The mathematician Theon (ca. 335 – ca. 405), father of Hypatia, is described in the tenth century Suda as "the man from the Mouseion." It is not known what connection he actually had with the Musaeum. Zacharias Rhetor and Aeneas of Gaza both speak of a physical space known as the "Mouseion" in the later 5th century.[17]

Legacy

This original Musaeum or Institution of the Muses was the source for the modern usage of the word museum. In early modern France, it denoted as much a community of scholars brought together under one roof as it did the collections themselves. French and English writers referred to these collections as a "cabinet" as in "a cabinet of curiosities." A catalogue of the 17th century collection of John Tradescant the Elder and his son John Tradescant the Younger was the founding core of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. It was published as Musaeum Tradescantianum: or, a Collection of Rarities. Preserved at South-Lambeth near London by John Tradescant, 1656.

References

- The relation of the institutions is still a matter of debate. The Musaeum is discussed by P.M. Fraser, Ptolemaic Alexandria (1972: vol. I:213-19 etc), and Mostafa el-Addabi, The Life and Fate of the Ancient Library of Alexandria (Paris 1990:84-90).

- There is no ancient source for the founding either of the Library or the Musaeum, Roger S. Bagnall notes, in "Alexandria: Library of Dreams", Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 146.4 (December 2002:348-362) p. 348. We rely instead on the self-confident but unreliable Byzantine scholar Johannes Tzetzes' remarks in an introduction to Aristotle.

- Entry Μουσείον at Liddell & Scott

- The Ptolemaic dynasty displayed these in their palace nearby.

- Bazin, The Museum Age 1967:16.

- "Mouseion". www.dailywriting.net. Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2018-03-18.

- An open loggia for walking and talking.

- The curved seat of an exedra is more accommodating to a group conversation than a bench in a straight line.

- Oikos signifies "household" in the broadest sense; an English analogy might be a university "commons".

- Strabo, Geography 17.1.8, noted by Bagnall 2002:57 note 39.

- "The Great Library of Alexandria". ldolphin.org. Retrieved 2018-03-18.

- Daniel Heller-Roazen, "Tradition's Destruction: On the Library of Alexandria" October, 100, Obsolescence (Spring 2002:133-1530 esp. p. 140.

- Suetonius, Claudius, 42

- Edward Jay Watts, (2008), City and School in Late Antique Athens and Alexandria, page 147. University of California Press

- Edward Jay Watts, (2008), City and School in Late Antique Athens and Alexandria, page 148. University of California Press

- Butler, Alfred, The Arab Conquest of Egypt – And the Last Thirty Years of the Roman Dominion, p. 411.

- Edward Jay Watts, (2008), City and School in Late Antique Athens and Alexandria, page 150. University of California Press

Further reading

- M MacLeod, Roy, The Library of Alexandria: centre of learning in the ancient world, 2000.

- El-Abbadi, Mostafa, The life and fate of the ancient library of Alexandria, 1990.

- Canfora, Luciano, The Vanished Library: A Wonder of the Ancient World, 1987. (The only modern history.)

- Young Lee, Paula, "The Musaeum of Alexandria and the formation of the 'Museum' in eighteenth-century France," in The Art Bulletin, September 1997.