Misogyny

Misogyny (/mɪˈsɒdʒɪni/) is the hatred of, contempt for, or prejudice against women or girls. It enforces sexism by punishing those who reject an inferior status for women and rewarding those who accept it. Misogyny manifests in numerous ways, including social exclusion, sex discrimination, hostility, androcentrism, patriarchy, male privilege, belittling of women, disenfranchisement of women, violence against women, and sexual objectification.[1][2] Misogyny can be found within sacred texts of religions, mythologies, and Western philosophy[1][3] and Eastern philosophy.

.jpg)

Definitions

According to sociologist Allan G. Johnson, "misogyny is a cultural attitude of hatred for females because they are female". Johnson argues that:

Misogyny .... is a central part of sexist prejudice and ideology and, as such, is an important basis for the oppression of females in male-dominated societies. Misogyny is manifested in many different ways, from jokes to pornography to violence to the self-contempt women may be taught to feel toward their own bodies.[4]

Sociologist Michael Flood at the University of Wollongong defines misogyny as the hatred of women, and notes:

Though most common in men, misogyny also exists in and is practiced by women against other women or even themselves. Misogyny functions as an ideology or belief system that has accompanied patriarchal, or male-dominated societies for thousands of years and continues to place women in subordinate positions with limited access to power and decision making. […] Aristotle contended that women exist as natural deformities or imperfect males […] Ever since, women in Western cultures have internalised their role as societal scapegoats, influenced in the twenty-first century by multimedia objectification of women with its culturally sanctioned self-loathing and fixations on plastic surgery, anorexia and bulimia.[5]

Philosopher Kate Manne of Cornell University defines misogyny as the attempt to control and punish women who challenge male dominance.[6] Manne finds the traditional "hatred of women" definition of misogyny too simplistic, noting it does not account for how perpetrators of misogynistic violence may love certain women; for example, their mothers.[7]:52 Instead, misogyny rewards women who uphold the status quo and punishes those who reject women's subordinate status.[6] Manne distinguishes sexism, which she says seeks to rationalize and justify patriarchy, from misogyny, which she calls the "law enforcement" branch of patriarchy:

[S]exist ideology will tend to discriminate between men and women, typically by alleging sex differences beyond what is known or could be known, and sometimes counter to our best current scientific evidence. Misogyny will typically differentiate between good women and bad ones, and punishes the latter. […] Sexism wears a lab coat; misogyny goes on witch hunts.[7]:79

Dictionaries define misogyny as "hatred of women"[8][9][10] and as "hatred, dislike, or mistrust of women".[11] In 2012, primarily in response to events occurring in the Australian Parliament,[12] the Macquarie Dictionary (which documents Australian English and New Zealand English) expanded the definition to include not only hatred of women but also "entrenched prejudices against women".[13] The counterpart of misogyny is misandry, the hatred or dislike of men; the antonym of misogyny is philogyny, the love or fondness of women.

Misogynous can be used as an adjectival form of the word.[14]

Historical usage

Classical Greece

In his book City of Sokrates: An Introduction to Classical Athens, J.W. Roberts argues that older than tragedy and comedy was a misogynistic tradition in Greek literature, reaching back at least as far as Hesiod.[15] The term misogyny itself comes directly into English from the Ancient Greek word misogunia (μισογυνία), which survives in several passages.

The earlier, longer, and more complete passage comes from a moral tract known as On Marriage (c. 150 BC) by the stoic philosopher Antipater of Tarsus.[16][17] Antipater argues that marriage is the foundation of the state, and considers it to be based on divine (polytheistic) decree. He uses misogunia to describe the sort of writing the tragedian Euripides eschews, stating that he "reject[s] the hatred of women in his writing" (ἀποθέμενος τὴν ἐν τῷ γράφειν μισογυνίαν). He then offers an example of this, quoting from a lost play of Euripides in which the merits of a dutiful wife are praised.[17][18]

The other surviving use of the original Greek word is by Chrysippus, in a fragment from On affections, quoted by Galen in Hippocrates on Affections.[19] Here, misogyny is the first in a short list of three "disaffections"—women (misogunia), wine (misoinia, μισοινία) and humanity (misanthrōpia, μισανθρωπία). Chrysippus' point is more abstract than Antipater's, and Galen quotes the passage as an example of an opinion contrary to his own. What is clear, however, is that he groups hatred of women with hatred of humanity generally, and even hatred of wine. "It was the prevailing medical opinion of his day that wine strengthens body and soul alike."[20] So Chrysippus, like his fellow stoic Antipater, views misogyny negatively, as a disease; a dislike of something that is good. It is this issue of conflicted or alternating emotions that was philosophically contentious to the ancient writers. Ricardo Salles suggests that the general stoic view was that "[a] man may not only alternate between philogyny and misogyny, philanthropy and misanthropy, but be prompted to each by the other."[21]

Aristotle has also been accused of being a misogynist; he has written that women were inferior to men. According to Cynthia Freeland (1994):

Aristotle says that the courage of a man lies in commanding, a woman's lies in obeying; that 'matter yearns for form, as the female for the male and the ugly for the beautiful'; that women have fewer teeth than men; that a female is an incomplete male or 'as it were, a deformity': which contributes only matter and not form to the generation of offspring; that in general 'a woman is perhaps an inferior being'; that female characters in a tragedy will be inappropriate if they are too brave or too clever[.][22]

In the Routledge philosophy guidebook to Plato and the Republic, Nickolas Pappas describes the "problem of misogyny" and states:

In the Apology, Socrates calls those who plead for their lives in court "no better than women" (35b)... The Timaeus warns men that if they live immorally they will be reincarnated as women (42b-c; cf. 75d-e). The Republic contains a number of comments in the same spirit (387e, 395d-e, 398e, 431b-c, 469d), evidence of nothing so much as of contempt toward women. Even Socrates' words for his bold new proposal about marriage... suggest that the women are to be "held in common" by men. He never says that the men might be held in common by the women... We also have to acknowledge Socrates' insistence that men surpass women at any task that both sexes attempt (455c, 456a), and his remark in Book 8 that one sign of democracy's moral failure is the sexual equality it promotes (563b).[23]

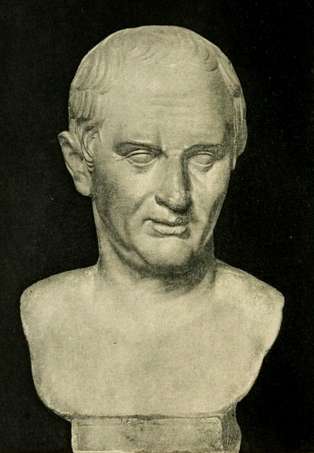

Misogynist is also found in the Greek—misogunēs (μισογύνης)—in Deipnosophistae (above) and in Plutarch's Parallel Lives, where it is used as the title of Heracles in the history of Phocion. It was the title of a play by Menander, which we know of from book seven (concerning Alexandria) of Strabo's 17 volume Geography,[24][25] and quotations of Menander by Clement of Alexandria and Stobaeus that relate to marriage.[26] A Greek play with a similar name, Misogunos (Μισόγυνος) or Woman-hater, is reported by Marcus Tullius Cicero (in Latin) and attributed to the poet Marcus Atilius.[27]

Cicero reports that Greek philosophers considered misogyny to be caused by gynophobia, a fear of women.[28]

It is the same with other diseases; as the desire of glory, a passion for women, to which the Greeks give the name of philogyneia: and thus all other diseases and sicknesses are generated. But those feelings which are the contrary of these are supposed to have fear for their foundation, as a hatred of women, such as is displayed in the Woman-hater of Atilius; or the hatred of the whole human species, as Timon is reported to have done, whom they call the Misanthrope. Of the same kind is inhospitality. And all these diseases proceed from a certain dread of such things as they hate and avoid.[28]

— Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones, 1st century BC.

In summary, Greek literature considered misogyny to be a disease—an anti-social condition—in that it ran contrary to their perceptions of the value of women as wives and of the family as the foundation of society. These points are widely noted in the secondary literature.[17]

English language

According to the Oxford English Dictionary the word entered English because of an anonymous proto-feminist play, Swetnam the Woman-Hater, published in 1620 in England.[29] The play is a criticism of anti-woman writer Joseph Swetnam, who it represents with the pseudonym Misogynos. The character of Misogynos is the origin of the term misogynist in English.[30]

The term was fairly rare until the mid-1970s. The publication of feminist Andrea Dworkin's 1974 critique Woman Hating popularized the idea. The term misogyny entered the lexicon of second-wave feminism. Dworkin and her contemporaries used the term to include not only a hatred or contempt of women, but the practice of controlling women with violence and punishing women who reject subordination.[30]

Misogyny was discussed worldwide in 2012 because of a viral video of a speech by Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard. Her parliamentary address is known as the Misogyny Speech. In the speech, Gillard powerfully criticized her opponents for holding her policies to a different standard than those of male politicians, and for speaking about her in crudely sexual terms.[31]

Gillard's usage of the word "misogyny" promoted re-evaluations of the word's published definitions. The Macquarie Dictionary revised its definition in 2012 to better match the way the word has been used over the prior 30 years.[32] The book Down Girl, which reconsidered the definition using the tools of analytic philosophy, was inspired in part by Gillard.[7]:83

Religion

Ancient Greek

In Misogyny: The World's Oldest Prejudice, Jack Holland argues that there is evidence of misogyny in the mythology of the ancient world. In Greek mythology according to Hesiod, the human race had already experienced a peaceful, autonomous existence as a companion to the gods before the creation of women. When Prometheus decides to steal the secret of fire from the gods, Zeus becomes infuriated and decides to punish humankind with an "evil thing for their delight". This "evil thing" is Pandora, the first woman, who carried a jar (usually described—incorrectly—as a box) which she was told to never open. Epimetheus (the brother of Prometheus) is overwhelmed by her beauty, disregards Prometheus' warnings about her, and marries her. Pandora cannot resist peeking into the jar, and by opening it she unleashes into the world all evil; labour, sickness, old age, and death.[33]

Buddhism

In his book The Power of Denial: Buddhism, Purity, and Gender, professor Bernard Faure of Columbia University argued generally that "Buddhism is paradoxically neither as sexist nor as egalitarian as is usually thought." He remarked, "Many feminist scholars have emphasized the misogynistic (or at least androcentric) nature of Buddhism" and stated that Buddhism morally exalts its male monks while the mothers and wives of the monks also have important roles. Additionally, he wrote:

While some scholars see Buddhism as part of a movement of emancipation, others see it as a source of oppression. Perhaps this is only a distinction between optimists and pessimists, if not between idealists and realists... As we begin to realize, the term "Buddhism" does not designate a monolithic entity, but covers a number of doctrines, ideologies, and practices--some of which seem to invite, tolerate, and even cultivate "otherness" on their margins.[34]

Christianity

Differences in tradition and interpretations of scripture have caused sects of Christianity to differ in their beliefs with regard to their treatment of women.

In The Troublesome Helpmate, Katharine M. Rogers argues that Christianity is misogynistic, and she lists what she says are specific examples of misogyny in the Pauline epistles. She states:

The foundations of early Christian misogyny — its guilt about sex, its insistence on female subjection, its dread of female seduction — are all in St. Paul's epistles.[35]

In K. K. Ruthven's Feminist Literary Studies: An Introduction, Ruthven makes reference to Rogers' book and argues that the "legacy of Christian misogyny was consolidated by the so-called 'Fathers' of the Church, like Tertullian, who thought a woman was not only 'the gateway of the devil' but also 'a temple built over a sewer'."[36]

However, some other scholars have argued that Christianity does not include misogynistic principles, or at least that a proper interpretation of Christianity would not include misogynistic principles. David M. Scholer, a biblical scholar at Fuller Theological Seminary, stated that the verse Galatians 3:28 ("There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus") is "the fundamental Pauline theological basis for the inclusion of women and men as equal and mutual partners in all of the ministries of the church."[37][38] In his book Equality in Christ? Galatians 3:28 and the Gender Dispute, Richard Hove argues that—while Galatians 3:28 does mean that one's sex does not affect salvation—"there remains a pattern in which the wife is to emulate the church's submission to Christ (Eph 5:21-33) and the husband is to emulate Christ's love for the church."[39]

In Christian Men Who Hate Women, clinical psychologist Margaret J. Rinck has written that Christian social culture often allows a misogynist "misuse of the biblical ideal of submission". However, she argues that this a distortion of the "healthy relationship of mutual submission" which is actually specified in Christian doctrine, where "[l]ove is based on a deep, mutual respect as the guiding principle behind all decisions, actions, and plans".[40] Similarly, Catholic scholar Christopher West argues that "male domination violates God's plan and is the specific result of sin".[41]

Islam

The fourth chapter (or sura) of the Quran is called "Women" (An-Nisa). The 34th verse is a key verse in feminist criticism of Islam.[42] The verse reads: "Men are the maintainers of women because Allah has made some of them to excel others and because they spend out of their property; the good women are therefore obedient, guarding the unseen as Allah has guarded; and (as to) those on whose part you fear desertion, admonish them, and leave them alone in the sleeping-places and beat them; then if they obey you, do not seek a way against them; surely Allah is High, Great."

In his book Popular Islam and Misogyny: A Case Study of Bangladesh, Taj Hashmi discusses misogyny in relation to Muslim culture (and to Bangladesh in particular), writing:

[T]hanks to the subjective interpretations of the Quran (almost exclusively by men), the preponderance of the misogynic mullahs and the regressive Shariah law in most "Muslim" countries, Islam is synonymously known as a promoter of misogyny in its worst form. Although there is no way of defending the so-called "great" traditions of Islam as libertarian and egalitarian with regard to women, we may draw a line between the Quranic texts and the corpus of avowedly misogynic writing and spoken words by the mullah having very little or no relevance to the Quran.[43]

In his book No god but God, University of Southern California professor Reza Aslan wrote that "misogynistic interpretation" has been persistently attached to An-Nisa, 34 because commentary on the Quran "has been the exclusive domain of Muslim men".[44]

Sikhism

Scholars William M. Reynolds and Julie A. Webber have written that Guru Nanak, the founder of the Sikh faith tradition, was a "fighter for women's rights" that was "in no way misogynistic" in contrast to some of his contemporaries.[45]

Scientology

In his book Scientology: A New Slant on Life, L. Ron Hubbard wrote the following passage:

A society in which women are taught anything but the management of a family, the care of men, and the creation of the future generation is a society which is on its way out.

In the same book, he also wrote:

The historian can peg the point where a society begins its sharpest decline at the instant when women begin to take part, on an equal footing with men, in political and business affairs, since this means that the men are decadent and the women are no longer women. This is not a sermon on the role or position of women; it is a statement of bald and basic fact.

These passages, along with other ones of a similar nature from Hubbard, have been criticised by Alan Scherstuhl of The Village Voice as expressions of hatred towards women.[46] However, Baylor University professor J. Gordon Melton has written that Hubbard later disregarded and abrogated much of his earlier views about women, which Melton views as merely echoes of common prejudices at the time. Melton has also stated that the Church of Scientology welcomes both genders equally at all levels—from leadership positions to auditing and so on—since Scientologists view people as spiritual beings.[47]

Misogynistic ideas among prominent western thinkers

Numerous influential Western philosophers have been expressed ideas that can be characterized as misogynistic, including Aristotle, René Descartes, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, David Hume, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, G. W. F. Hegel, Arthur Schopenhauer, Friedrich Nietzsche, Charles Darwin, Sigmund Freud, Otto Weininger, Oswald Spengler, and John Lucas.[3] Because of the influence of these thinkers, feminist scholars trace misogyny in western culture to these philosophers and their ideas.[48]

Aristotle

Aristotle believed women were inferior and described them as "deformed males".[49][50] In his work Politics, he states

as regards the sexes, the male is by nature superior and the female inferior, the male ruler and the female subject 4 (1254b13-14).[50]

Another example is Cynthia's catalog where Cynthia states "Aristotle says that the courage of a man lies in commanding, a woman's lies in obeying; that 'matter yearns for form, as the female for the male and the ugly for the beautiful'; that women have fewer teeth than men; that a female is an incomplete male or 'as it were, a deformity'.[49] Aristotle believed that men and women naturally differed both physically and mentally. He claimed that women are "more mischievous, less simple, more impulsive ... more compassionate[,] ... more easily moved to tears[,] ... more jealous, more querulous, more apt to scold and to strike[,] ... more prone to despondency and less hopeful[,] ... more void of shame or self-respect, more false of speech, more deceptive, of more retentive memory [and] ... also more wakeful; more shrinking [and] more difficult to rouse to action" than men.[51]

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau is well known for his views against equal rights for women for example in his treatise Emile, he writes: "Always justify the burdens you impose upon girls but impose them anyway... . They must be thwarted from an early age... . They must be exercised to constraint, so that it costs them nothing to stifle all their fantasies to submit them to the will of others." Other quotes consist of "closed up in their houses", "must receive the decisions of fathers and husbands like that of the church".[52]

Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer has been noted as a misogynist by many such as the philosopher, critic, and author Tom Grimwood.[53] In a 2008 article published in the philosophical journal of Kritique, Grimwood argues that Schopenhauer's misogynistic works have largely escaped attention despite being more noticeable than those of other philosophers such as Nietzsche.[53] For example, he noted Schopenhauer's works where the latter had argued women only have "meagre" reason comparable that of "the animal" "who lives in the present". Other works he noted consisted of Schopenhauer's argument that women's only role in nature is to further the species through childbirth and hence is equipped with the power to seduce and "capture" men.[53] He goes on to state that women's cheerfulness is chaotic and disruptive which is why it is crucial to exercise obedience to those with rationality. For her to function beyond her rational subjugator is a threat against men as well as other women, he notes. Schopenhauer also thought women's cheerfulness is an expression of her lack of morality and incapability to understand abstract or objective meaning such as art.[53] This is followed up by his quote "have never been able to produce a single, really great, genuine and original achievement in the fine arts, or bring to anywhere into the world a work of permanent value".[53] Arthur Schopenhauer also blamed women for the fall of King Louis XIII and triggering the French Revolution, in which he was later quoted as saying:[53]

"At all events, a false position of the female sex, such as has its most acute symptom in our lady-business, is a fundamental defect of the state of society. Proceeding from the heart of this, it is bound to spread its noxious influence to all parts."[53]

Schopenhauer has also been accused of misogyny for his essay "On Women" (Über die Weiber), in which he expressed his opposition to what he called "Teutonico-Christian stupidity" on female affairs. He argued that women are "by nature meant to obey" as they are "childish, frivolous, and short sighted".[3] He claimed that no woman had ever produced great art or "any work of permanent value".[3] He also argued that women did not possess any real beauty:[54]

It is only a man whose intellect is clouded by his sexual impulse that could give the name of the fair sex to that under-sized, narrow-shouldered, broad-hipped, and short-legged race; for the whole beauty of the sex is bound up with this impulse. Instead of calling them beautiful there would be more warrant for describing women as the unaesthetic sex.

Nietzsche

In Beyond Good and Evil, Friedrich Nietzsche stated that stricter controls on women was a condition of "every elevation of culture".[55] In his Thus Spoke Zarathustra, he has a female character say "You are going to women? Do not forget the whip!"[56] In Twilight of the Idols, Nietzsche writes "Women are considered profound. Why? Because we never fathom their depths. But women aren't even shallow."[57] There is controversy over the questions of whether or not this amounts to misogyny, whether his polemic against women is meant to be taken literally, and the exact nature of his opinions of women.[58]

Hegel

Hegel's view of women can be characterized as misogynistic.[59] Passages from Hegel's Elements of the Philosophy of Right illustrate the criticism:[60]

Women are capable of education, but they are not made for activities which demand a universal faculty such as the more advanced sciences, philosophy and certain forms of artistic production... Women regulate their actions not by the demands of universality, but by arbitrary inclinations and opinions.

Violence

Misogynist terrorism

Misogynist terrorism is an extreme form of misogynist violence. Certain mass murderers, often identifying as incels, have explained their killings as anti-feminist acts, describing an attitude of entitlement to sex with attractive women, a desire to seek vengeance for the perception of being rejected, and a drive to put women "in their place."[61] (Misogyny is common among mass killers, even when it is not the primary motivation.)[62]

As is typical of terrorism, these acts are intended to cause widespread fear. Any woman may reasonably be unsettled about the potential of being targeted, notes Kate Manne, because often victims of these killings are treated as interchangeable. Women are targeted merely because they fit a certain type rather than because they have any particular relationship to the killer.[7]:109

Since 2018 counter-terrorism professionals such as ICCT and START describe this form of terrorism as a "rising threat" and include misogyny or male supremacy among the ideologies they track.[63] Feminist Jessica Valenti was influential in recognizing these acts as misogynist terrorism.[61]

Domestic violence

The majority of Domestic violence and Intimate partner violence targets women and is committed by men. In particular, men with a rigid, narrow view of how to be a man are more likely to commit or tolerate this form of violence. The belief that men should be forceful and dominant in relationships and households makes a man more likely to hit, abuse, coerce, and sexually harass a woman. On the other hand, flexible and egalitarian ideas about manhood typically lead to less violence.[64]

Online misogyny

Misogynistic rhetoric is prevalent online and has grown more aggressive over time.[65][66] Online misogyny includes both individual attempts to intimidate and denigrate women, and also coordinated, collective attempts such as vote brigading and the Gamergate antifeminist harassment campaign.[67]

Coordinated attacks

The most likely targets for misogynistic attacks by coordinated groups are women who are visible in the public sphere, women who speak out about the threats they receive, and women who are perceived to be associated with feminism or feminist gains. Authors of misogynistic messages are usually anonymous or otherwise difficult to identify. Their rhetoric involves misogynistic epithets and graphic or sexualized imagery. It centers on the women's physical appearance, and prescribes sexual violence as a corrective for the targeted women. Examples of famous women who spoke out about misogynistic attacks are Anita Sarkeesian, Laurie Penny, Caroline Criado Perez, Stella Creasy, and Lindy West.[65]

These attacks do not always remain online only. The government of Brazil makes misogynistic attacks against Patrícia Campos Mello and other female journalists in conjunction with street-level threats and violence.[68] Swatting was used to bring Gamergate attacks into the physical world.[69]

Language used

The insults and threats directed at different women tend to be very similar. Sady Doyle who has been the target of online threats noted the "overwhelmingly impersonal, repetitive, stereotyped quality" of the abuse, the fact that "all of us are being called the same things, in the same tone".[65]

A 2016 study conducted by the think tank Demos found that the majority of Twitter messages containing the words "whore" or "slut" were advertisements for pornography. Of those that are not, a majority used the terms in a non-aggressive way, such a discussion of slut-shaming. Of those that used the terms "whore" or "slut" in an aggressive, insulting way, about half were women and half were men. Twitter users most frequently targeted by women with aggressive insults were celebrities, such as Beyoncé Knowles.[70]

Psychological impact

Internalized misogyny

Internalized sexism is when an individual enacts sexist actions and attitudes towards themselves and people of their own sex.[71] On a larger scale, internalized sexism falls under the broad topic of internalized oppression, which "consists of oppressive practices that continue to make the rounds even when members of the oppressor group are not present".[71] Women who experience internalized misogyny may express it through minimizing the value of women, mistrusting women, and believing gender bias in favor of men.[72] Women, after hearing men demean the value and skills of women repeatedly, eventually internalize their beliefs and apply the misogynistic beliefs to themselves and other women.[73] A common manifestation of internalized misogyny is lateral violence.

Abuse and harassment

Misogyny causes sexual harassment.[74] Harassment is associated with decreased psychological well-being, including diminished self-confidence and greater risk of anxiety and depression.[75]

Misogynist attitudes lead to the physical, sexual, and emotional abuse of gender nonconforming boys in childhood.[76]

Feminist theory

"Good" versus "bad" women

Many feminists have written that the notions of "good" women and "bad" women are imposed upon women in order to control them. Women who are easy to control, or who advocate for their own oppression, may be told they are good. The categories of bad and good also cause fighting among women; Helen Lewis identifies this "long tradition of regulating female behavior by defining women in opposition to one another" as the architecture of misogyny.[77]

The Madonna–whore dichotomy or virgin/whore dichotomy is the perception of women as either good and chaste or as bad and promiscuous. Belief in this dichotomy leads to misogyny, according to the feminist perspective, because the dichotomy appears to justify policing women's behavior. Misogynists seek to punish "bad" women for their sexuality.[78] Author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie observes that when women describe being harassed or assaulted (as in the #MeToo movement) they are viewed as deserving sympathy only if they are "good" women — nonsexual, and perhaps helpless.[79]

In her 1974 book Woman Hating, Andrea Dworkin uses traditional fairy tales to illustrate misogyny. Fairy tales designate certain women as "good", for example Sleeping Beauty and Snow White, who are inert, passive characters. Dworkin observed that these characters "never think, act, initiate, confront, resist, challenge, feel, care, or question. Sometimes they are forced to do housework." In contrast, the "evil" women who populate fairy tales are queens, witches, and other women with power. Further, men in fairy tales are said to be good kings and good husbands irrespective of their actions. For Dworkin, this illustrates that under misogyny only powerless women are allowed to be seen as good. No similar judgement is applied to men.[80]

In her book Right-Wing Women, Dworkin adds that powerful women are tolerated by misogynists provided women use their power to reenforce the power of men and to oppose feminism. Dworkin gives Phyllis Schlafly and Anita Bryant as examples of powerful women tolerated by antifeminists only because they advocated for their own oppression. Women may even be worshiped or called superior to men if they are sufficiently "good", meaning obedient or inert.[81]

Philosopher Kate Manne argues that the word "misogyny" as used by modern feminists denotes not a generalized hatred of women, but instead the system of distinguishing good from bad women. Misogyny is like a police force, Manne writes, that rewards or punishes women based on these judgements.[7]:79

The patriarchal bargain

In the late 20th century, second-wave feminist theorists argued that misogyny is both a cause and a result of patriarchal social structures.[82]

Economist Deniz Kandiyoti has written that colonizers of the Middle East, Africa, and Asia kept conquered armies of men under control by offering them complete power over women. She calls this the "patriarchal bargain." Men who were interested in accepting the bargain were promoted to leadership by colonial powers, causing the colonized societies to become more misogynistic.[83]

Sociologist Michael Flood has argued that "misandry lacks the systemic, trans-historic, institutionalized, and legislated antipathy of misogyny".[84]

Contempt for the feminine

Julia Serano defines misogyny as not only hatred of women per se, but the "tendency to dismiss and deride femaleness and femininity." In this view, misogyny also causes homophobia against gay men because gay men are stereotyped as feminine and weak; misogyny likewise causes anxiety among straight men that they will be seen as unmanly.[85] Serano's book Whipping Girl argues that most anti-trans sentiment directed at trans women should be understood as misogyny. By embracing femininity, the book argues, trans women cast doubt on the superiority of masculinity.[86]

British legal situation

In recent years, there has been increasing discussion in the UK of misogyny being added to the list of aggravating factors that are commonly referred to by the media as “hate crimes”. Aggravating factors in criminal sentencing currently include hostility to a victim due to characteristics such as sexuality, race or disability.[87]

In 2016, Nottinghamshire Police began a pilot project to record misogynistic behaviour as either hate crime or hate incidents, depending on whether the action was a criminal offence.[88] Over two years (April 2016-March 2018) there were 174 reports made, of which 73 were classified as crimes and 101 as incidents.[89]

In September 2018, it was announced that the Law Commission would conduct a review into whether misogynistic conduct, as well as hostility due to ageism, misandry or towards groups such as goths, should be treated as a hate crime.[90][91]

In October 2018, two senior police officers, Sara Thornton, chair of the National Police Chiefs' Council, and Cressida Dick, Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, stated that police forces should focus on more serious crimes such as burglary and violent offences, and not on recording incidents which are not crimes.[92] Thornton said that "treating misogyny as a hate crime is a concern for some well-organised campaigning organisations", but that police forces "do not have the resources to do everything".[93]

Criticism of the concept

Camille Paglia, a self-described "dissident feminist" who has often been at odds with other academic feminists, argues that there are serious flaws in the Marxism-inspired[94] interpretation of misogyny that is prevalent in second-wave feminism. In contrast, Paglia argues that a close reading of historical texts reveals that men do not hate women but fear them.[95] Christian Groes-Green has argued that misogyny must be seen in relation to its opposite which he terms philogyny. Criticizing R. W. Connell's theory of hegemonic masculinities, he shows how philogynous masculinities play out among youth in Maputo, Mozambique.[96]

See also

- Exploitation of women in mass media

- Gender studies

- Honor killing

- Men Going Their Own Way

- Misanthropy

- Misandry

- Misogynoir

- Misogyny and mass media

- Misogyny in hip hop culture

- Misogyny in horror films

- Misogyny in sports

- Object relations theory

- Sexuality in music videos

- Stoicorum Veterum Fragmenta

- The Bro Code: How Contemporary Culture Creates Sexist Men

- Transmisogyny

- Wife selling

- Women's rights

Notes and references

- Code, Lorraine (2000). Encyclopedia of Feminist Theories (1st ed.). London: Routledge. p. 346. ISBN 978-0-415-13274-9.

- Kramarae, Cheris (2000). Routledge International Encyclopedia of Women. New York: Routledge. pp. 1374–1377. ISBN 978-0-415-92088-9.

- Clack, Beverley (1999). Misogyny in the Western Philosophical Tradition: A Reader. New York: Routledge. pp. 95–241. ISBN 978-0-415-92182-4.

- Johnson, Allan G (2000). The Blackwell dictionary of sociology: A user's guide to sociological language. ISBN 978-0-631-21681-0. Retrieved November 21, 2011., ("ideology" in all small capitals in original).

- Flood, Michael (July 18, 2007). International encyclopedia of men and masculinities. ISBN 978-0-415-33343-6.

- Illing, Sean (March 7, 2020). "What we get wrong about misogyny". Vox. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- Manne, Kate (2019). Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny. Ithaca, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190604981.

- The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles (Oxford: Clarendon Press (Oxford Univ. Press), [4th] ed. 1993 (ISBN 0-19-861271-0)) (SOED) ("[h]atred of women").

- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (Boston, Mass.: Houghton Mifflin, 1992 (ISBN 0-395-44895-6)) ("[h]atred of women").

- Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language Unabridged (G. & C. Merriam, 1966) ("a hatred of women").

- Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary (N.Y.: Random House, 2d ed. 2001 (ISBN 0-375-42566-7)).

- "Transcript of Julia Gillard's speech". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- Daley, Gemma (17 October 2012). "Macquarie Dictionary has last word on misogyny". Archived from the original on 19 October 2012.

- "Definition of "misogyny"". Dictionary.com. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- Roberts, J.W (2002-06-01). City of Sokrates: An Introduction to Classical Athens. ISBN 978-0-203-19479-9.

- The editio princeps is on page 255 of volume three of Stoicorum Veterum Fragmenta (SVF, Old Stoic Fragments), see External links.

- A recent critical text with translation is in Appendix A to Will Deming, Paul on Marriage and Celibacy: The Hellenistic Background of 1 Corinthians 7, pp. 221–226. Misogunia appears in the accusative case on page 224 of Deming, as the fifth word in line 33 of his Greek text. It is split over lines 25–26 in von Arnim.

- 38-43, fr. 63, in von Arnim, J. (ed.). Stoicorum Veterum Fragmenta. Vol. 3. Leipzig: Teubner, 1903.

- SVF 3:103. Misogyny is the first word on the page.

- Teun L. Tieleman, Chrysippus' on Affections: Reconstruction and Interpretations, (Leiden: Brill Publishers, 2003), p. 162. ISBN 90-04-12998-7

- Ricardo Salles, Metaphysics, Soul, and Ethics in Ancient Thought: Themes from the Work of Richard Sorabji, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2005), 485.

- "Feminist History of Philosophy (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". Plato.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2013-10-01.

- Pappas, Nickolas (2003-09-09). Routledge philosophy guidebook to Plato and the Republic. ISBN 978-0-415-29996-1.

- Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott, A Greek–English Lexicon (LSJ), revised and augmented by Henry Stuart Jones and Roderick McKenzie, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1940). ISBN 0-19-864226-1

- Strabo,Geography, Book 7 [Alexandria] Chapter 3.

- Menander, The Plays and Fragments, translated by Maurice Balme, contributor Peter Brown, Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-19-283983-7

- He is supported (or followed) by Theognostus the Grammarian's 9th century Canones, edited by John Antony Cramer, Anecdota Graeca e codd. manuscriptis bibliothecarum Oxoniensium, vol. 2, (Oxford University Press, 1835), p. 88.

- Marcus Tullius Cicero, Tusculanae Quaestiones, Book 4, Chapter 11.

- "misogynist". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- Aron, Nina Renata (March 8, 2019). "What Does Misogyny Look Like?". The New York Times. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- Lester, Amelia (October 9, 2012). "Ladylike: Julia Gillard's Misogyny Speech". The New Yorker. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- "Dictionary changes 'misogyny' definition after Australian PM's furious attack on conservative leader". National Post. Reuters. October 17, 2012. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- Holland, J: Misogyny: The World's Oldest Prejudice, pp. 12–13. Avalon Publishing Group, 2006.

- "Sample Chapter for Faure, B.: The Power of Denial: Buddhism, Purity, and Gender". Press.princeton.edu. Archived from the original on 2013-10-05. Retrieved 2013-10-01.

- Rogers, Katharine M. The Troublesome Helpmate: A History of Misogyny in Literature, 1966.

- Ruthven, K. K (1990). Feminist literary studies: An introduction. Cambridge University Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-521-39852-7.

christian misogyny.

- "Galatians 3:28 – prooftext or context?". The council on biblical manhood and womanhood. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- Hove, Richard. Equality in Christ? Galatians 3:28 and the Gender Dispute (Wheaton: Crossway, 1999), p. 17.

- Campbell, Ken M (October 1, 2003). Marriage and family in the biblical world. ISBN 978-0-8308-2737-4.

- Rinck, Margaret J. (1990). Christian Men Who Hate Women: Healing Hurting Relationships. Zondervan. pp. 81–85. ISBN 978-0-310-51751-1.

- Weigel, Christopher West ; with a foreword by George (2003). Theology of the body explained : a commentary on John Paul II's "Gospel of the body". Leominster, Herefordshire: Gracewing. ISBN 978-0-85244-600-3.

- "Verse 34 of Chapter 4 is an oft-cited Verse in the Qur'an used to demonstrate that Islam is structurally patriarchal, and thus Islam internalizes male dominance." Dahlia Eissa, "Constructing the Notion of Male Superiority over Women in Islam: The influence of sex and gender stereotyping in the interpretation of the Qur'an and the implications for a modernist exegesis of rights", Occasional Paper 11 in Occasional Papers (Empowerment International, 1999).

- Hashmi, Taj. Popular Islam and Misogyny: A Case Study of Bangladesh. Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- Nomani, Asra Q. (October 22, 2006). "Clothes Aren't the Issue". Washington Post.

- Julie A. Webber (2004). Expanding curriculum theory: dis/positions and lines of flight. Psychology Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-8058-4665-2.

- Scherstuhl, Alan (June 21, 2010). "The Church of Scientology does not want you to see L. Ron Hubbard's woman-hatin' book chapter". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on June 25, 2010.

- "Gender and Sexuality". Patheos.com. 2012-07-26. Retrieved 2013-10-01.

- Witt, Charlotte; Shapiro, Lisa (2017), Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), "Feminist History of Philosophy", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2017 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 2018-08-21

- Witt, Charlotte; Shapiro, Lisa (2016-01-01). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Feminist History of Philosophy (Spring 2016 ed.).

- Smith, Nicholas D. (1983). "Plato and Aristotle on the Nature of Women". Journal of the History of Philosophy. 21 (4): 467–478. doi:10.1353/hph.1983.0090.

- History of Animals, 608b. 1–14

- Blum, C. (2010). "Rousseau and Feminist Revision". Eighteenth-Century Life. 34 (3): 51–54. doi:10.1215/00982601-2010-012.

- Grimwood, Tom (2008-01-01). "The Limits of Misogyny: Schopenhauer, "On Women"". Kritike: An Online Journal of Philosophy. 2 (2): 131–145. doi:10.3860/krit.v2i2.854.

- Durant, Will (1983). The Story of Philosophy. New York, N.Y.: Simon and Schuster. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-671-20159-3.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich (1886). Beyond Good and Evil. Germany. Retrieved January 23, 2014.

- Burgard, Peter J. (May 1994). Nietzsche and the Feminine. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8139-1495-4.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich (1889). Twilight of the Idols. Germany. ISBN 978-0-14-044514-5. Retrieved January 23, 2014.

- Robert C. Holub, Nietzsche and The Women's Question. Coursework for Berkeley University.

- Gallagher, Shaun (1997). Hegel, history, and interpretation. SUNY Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-7914-3381-2.

- Alanen, Lilli; Witt, Charlotte (2004). Feminist Reflections on the History of Philosophy. ISBN 978-1-4020-2488-7.

- Valenti, Jessica (April 26, 2018). "When Misogynists Become Terrorists". The New York Times. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- Bosman,, Julie; Taylor,, Kate; Arango, Tim (August 10, 2019). "A Common Trait Among Mass Killers: Hatred Toward Women". The New York Times. Retrieved July 23, 2020.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- DiBranco, Alex (February 10, 2020). "Male Supremacist Terrorism as a Rising Threat". International Centre for Counter-Terrorism. The Hague. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- Flood, Michael (November 6, 2019). "Forceful and dominant: men with sexist ideas of masculinity are more likely to abuse women". The Conversation. Queensland University of Technology. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- Jane, Emma Alice (2014). "'Back to the kitchen, cunt': speaking the unspeakable about online misogyny". Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies. 28 (4): 558–570. doi:10.1080/10304312.2014.924479.

- Philipovic, Jill (2007). "Blogging While Female: How Internet Misogyny Parallels Real-World Harassment". Yale Journal of Law and Feminism. 19 (2): 295–303.

- Nieborg, David; Foxman, Maxwell (February 14, 2018). "Mainstreaming Misogyny: The Beginning of the End and the End of the Beginning in Gamergate Coverage". In Vickery J.; Everbach T. (eds.). Mediating Misogyny. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 111–130. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-72917-6_6. ISBN 978-3-319-72916-9.

- Mello, Patrícia Campos (August 4, 2020). "Brazil's Troll Army Moves Into the Streets". The New York Times. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- Robertson, Adi (January 4, 2015). "'About 20' police officers sent to Gamergate critic's former home after fake hostage threat". The Verge. Retrieved August 4, 2020.

- The use of misogynistic terms on Twitter

- Bearman, Steve, Neill Korobov, and Avril Thorne. "The fabric of internalized sexism." Journal of Integrated Social Sciences 1, no. 1 (2009): 10-47.

- Szymanski, Gupta, and Carr. 2009. "Internalized Misogyny as a Moderator of the Link between Sexist Events and Women’s Psychological Distress." Sex Roles 16, no. 1-2: 101–109.

- Bearman, Steve; Korobov, Neill; Thorne, Avril. 2009. "The fabric of internalized sexism." Journal of Integrated Social Sciences 1, no. 1: 10-47.

- Srivastava, Kalpana; Chaudhury, Suprakash; Bhat, P. S.; Sahu, Samiksha (2017). "Misogyny, feminism, and sexual harassment". Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 26 (2): 111–113. doi:10.4103/ipj.ipj_32_18.

- Houle, Jason N.; Staff, Jeremy; Mortimer, Jeylan T.; Uggen, Christopher; Blackstone, Amy (July 1, 2011). "The impact of sexual harassment on depressive symptoms during the early occupational career". Society and Mental Health. 1 (2): 89–105. doi:10.1177/2156869311416827. PMID 22140650.

- Brooks, Franklin L. (October 11, 2008). "Beneath Contempt: The Mistreatment of Non-Traditional/Gender Atypical Boys". Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services. 12 (1–2): 107–115. doi:10.1300/J041v12n01_06.

- Lewis, Helen (January 16, 2020). "Meghan, Kate, and the Architecture of Misogyny". The Atlantic. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- Kahalon, Rotem; Bareket, Orly; Vial, Andrea C.; Sassenhagen, Nora; Becker, Julia C.; Shnabel, Nurit (May 2, 2019). "The Madonna-Whore Dichotomy Is Associated With Patriarchy Endorsement: Evidence From Israel, the United States, and Germany". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 43 (3): 348–367. doi:10.1177/0361684319843298.

- Marchese, David (July 9, 2018). "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: The novelist on being a "feminist icon," Philip Roth's humanist misogyny, and the sadness in Melania Trump". Vulture. Vox Media. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Dworkin, Andria (1974). Woman Hating (PDF). New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 9780525474234.

- For an interpretation, see: Gupta, Shivangi (July 12, 2019). "Book Review: Woman Hating By Andrea Dworkin". Feminism in India. FII Media Private Limited. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- Dworkin, Andria (1983). Right-Wing Women. New York: Perigee Books. ISBN 9780399506710.

- E.g., Kate Millet's Sexual Politics, adapted from her doctoral dissertation is normally cited as the originator of this viewpoint; though Katharine M Rogers had also published similar ideas previously.

- Fisher, Max (April 25, 2012). "The Real Roots of Sexism in the Middle East (It's Not Islam, Race, or 'Hate')". The Atlantic. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- Flood, Michael (2007-07-18). International encyclopedia of men and masculinities. ISBN 978-0-415-33343-6.

- Berlatsky, Noah (June 5, 2014). "Can Men Really Be Feminists?". The Atlantic. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- Serano, Julia (2007). Whipping Girl. Berkeley: Seal Press. p. 15. ISBN 1580051545.

- "Aggravating and mitigating factors", Sentencing Council.

- Brooks, Libby, "UK police chiefs urged to adopt harassment of women as hate crime", The Guardian, July 9, 2018.

- "Misogyny hate crime in Nottinghamshire gives 'shocking' results", BBC News, July 9, 2018.

- "Misogyny could become hate crime as legal review is announced", BBC News, September 6, 2018.

- Grierson, Jamie, "Review of UK hate crime law to consider misogyny and ageism", The Guardian, October 16, 2018.

- Tobin, Olivia, "Met chief Cressida Dick backs senior police officer Sara Thornton on tackling burglars and violence ahead of hate crimes", Evening Standard, November 2, 2018.

- "Focus on violent crime not misogyny, says police chief", BBC News, November 1, 2018.

- "Marxist feminists reduced the historical cult of woman’s virginity to her property value, her worth on the male marriage market.", Paglia, 1991, Sexual Persona, p. 27.

- Paglia, Camille (1991). Sexual Personae, NY: Vintage, Chapter 1 and passim.

- Groes-Green, Christian (2011). "Philogynous Masculinities: Contextualizing Alternative Manhood in Mozambique". Men and Masculinities. 15 (2): 91–111. doi:10.1177/1097184x11427021.

Bibliography

- Boteach, Shmuley. Hating Women: America's Hostile Campaign Against the Fairer Sex. 2005.

- Brownmiller, Susan. Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1975.

- Clack, Beverley, comp. Misogyny in the Western Philosophical Tradition: a reader. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1999.

- Dijkstra, Bram. Idols of Perversity: Fantasies of Feminine Evil. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Chodorow, Nancy. The Reproduction of Mothering: Psychoanalysis and the Sociology of Gender. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley, 1978.

- Dworkin, Andrea. Woman Hating. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1974.

- Ellmann, Mary. Thinking About Women. 1968.

- Ferguson, Frances and R. Howard Bloch. Misogyny, Misandry, and Misanthropy. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0-520-06544-4

- Forward, Susan, and Joan Torres. Men Who Hate Women and the Women Who Love Them: When Loving Hurts and You Don't Know Why. Bantam Books, 1986. ISBN 0-553-28037-6

- Gilmore, David D. Misogyny: the Male Malady. 2001.

- Haskell, Molly. From Reverence to Rape: The Treatment of Women in the Movies. 1974. University of Chicago Press, 1987.

- Holland, Jack. Misogyny: The World's Oldest Prejudice. 2006.

- Johnson, Allan G. 'Misogyny'. In Blackwell Dictionary of Sociology: A User's Guide to Sociological Language. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2000.

- Kipnis, Laura. The Female Thing: Dirt, Sex, Envy, Vulnerability. 2006. ISBN 0-375-42417-2

- Klein, Melanie. The Collected Writings of Melanie Klein. 4 volumes. London: Hogarth Press, 1975.

- Lewis, Helen. Difficult Women: A History Of Feminism In 11 Fights. Jonathan Cape, 2020.

- Manne, Kate. Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny. Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Marshall, Gordon. 'Misogyny'. In Oxford Dictionary of Sociology. Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Millett, Kate. Sexual Politics. New York: Doubleday, 1970.

- Morgan, Fidelis. A Misogynist's Source Book.

- Patai, Daphne, and Noretta Koertge. Professing Feminism: Cautionary Tales from the Strange World of Women's Studies. 1995. ISBN 0-465-09827-4

- Penelope, Julia. Speaking Freely: Unlearning the Lies of our Fathers' Tongues. Toronto: Pergamon Press Canada, 1990.

- Rogers, Katharine M. The Troublesome Helpmate: A History of Misogyny in Literature. 1966.

- Smith, Joan. Misogynies. 1989. Revised 1993.

- Tumanov, Vladimir. "Mary versus Eve: Paternal Uncertainty and the Christian View of Women." Neophilologus 95 (4) 2011: 507–521.

- von Arnim, J. (ed.). Stoicorum veterum fragmenta Vol. 3. Leipzig: Teubner, 1903.

- World Health Organization Multi-country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women* 2005.

External links

| Look up misogyny in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Misogyny |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Misogyny. |