Picc-Vic tunnel

Picc-Vic was a proposed, and later cancelled, underground railway designed in the early 1970s with the purpose of connecting two major mainline railway termini in Manchester city centre, England. The name Picc-Vic was a contraction of the two station names, Manchester Piccadilly and Manchester Victoria. The proposal envisaged the construction of an underground rail tunnel across Manchester city centre. The scheme was abandoned in 1977 during its proposal stages due to excessive costs, and that the scheme still retained two large and expensive-to-maintain terminal stations in Manchester; other similar sized cities had reduced their terminals to one.

| Picc-Vic Tunnel | |

|---|---|

| |

An artist's impression of the Picc-Vic line (1971)[1] | |

| Overview | |

| Type | Commuter rail |

| System | Greater Manchester Transport/British Rail |

| Status | Abandoned proposal |

| Locale | Manchester, England |

| Termini | Manchester Victoria Manchester Piccadilly |

| Stations | 5 |

| Services | 1 |

| Operation | |

| Opened | 1977 (planned) |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 2.75 mi (4.43 km) |

| Track length | 2.75 mi (4.43 km) |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) |

| Highest elevation | Underground |

In 1992, the Metrolink system opened and linked both stations via tram, negating the requirement for a direct rail connection to an extent. In 2017, the Ordsall Chord became operational; an overground railway scheme directly linking Manchester Piccadilly and Manchester Victoria in a comparable fashion to Picc-Vic.[2]

History

Background

The railway network built in the 19th and 20th centuries by numerous railway companies resulted in various unconnected railway termini around the periphery of Manchester city centre. Unlike central London, which had linked its stations with the London Underground, Manchester had a large area of its central business district which was not served by rail transport.

Proposal

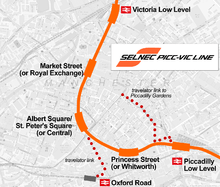

The South-East Lancashire and North-East Cheshire Passenger Transport Executive (SELNEC PTE) - the local transport authority which became the Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Executive (GMPTE) in 1974 (now Transport for Greater Manchester - TfGM) - made a proposal in 1971 to connect the unjoined railways running through Manchester city centre under the Picc-Vic scheme. The Picc-Vic proposal envisaged joining the two halves of the rail network by constructing new tunnels under the city centre, connecting Manchester's two main railway stations, Piccadilly and Victoria. This new underground railway would be served by three new underground stations, joining together the regional, national and local rail networks with an underground rapid transit system for Manchester.[1]

The objectives of the Picc-Vic tunnel were threefold:

- To improve the distribution arrangements from the existing railway stations which are on the periphery of the central core

- To link the separated northern and southern railway systems

- To improve passenger movement within the central area.

It formed part of a four-phase, Long Term Strategy for GMPTE over 25 years, which included bus priority and an East-West railway network, as well as a light rapid transport system.

Cancellation

SELNEC made an infrastructure grant application to central government to fund the construction of the Picc-Vic line. In the early 1970s, Britain was facing economic difficulties and the Chancellor of the Exchequer Anthony Barber announced a £500 million reduction in public expenditure. In August 1973, the Minister for Transport Industries John Peyton rejected the grant application, stating that "there is no room for a project as costly as Picc-Vic before 1975 at the earliest".[3]

An underground excavation and construction project required a large initial outlay of public funds, and when the Greater Manchester County Council took on the project, it was unable to secure the necessary funding from central government. The Picc-Vic scheme was abandoned in 1977 owing to excessive cost.[4]

Specification

Route

Manchester Picc-Vicc tunnel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The proposed new link would have been 2 3⁄4 miles (4.4 km) long, and run from Ardwick Junction, a mile south of Piccadilly Station, to Queens Road Junction on the Bury line, about three-quarters of a mile north of Victoria. Just over 2 miles (3 km) of the new line would have been in tunnel, most of which would be 60–70 feet (18–21 m) beneath the centre of Manchester. The southern approach ramp would have been built on the surface and in a shallow tunnel.

There would have been two separate tracks, each electrified on the 25 kV AC system. In the deep tunnel section separate bores were to be tunnelled for each track. The track was to consist of continuous welded rails on concrete foundations - 'slab track'. The tunnel was to be controlled by British Rail's standard three-aspect colour light signals together with their automatic warning system (AWS). This would have permitted train frequencies of 90 seconds, although initial proposals envisaged a 2.5 minute headway.

Once opened, the underground line would have enabled through-running for trains across the city region by linking up several existing railway lines, including the Bury Line, Crewe–Manchester line, Hope Valley line, Stafford–Manchester line, and Styal line.

The planned course of the Picc-Vic tunnel would not follow a direct route across the city centre but instead would skirt around the south of the city centre before curving north towards Victoria. An obstacle to the construction of the line was the subterranean Guardian telephone exchange, a subterranean structure that extended beneath the city centre south of Piccadilly Gardens. The exchange had been designated as a nuclear bunker, and while SELNEC planners were aware of this structure, they were unable to mention it publicly as they were forced to sign the Official Secrets Act in 1971.[3]

Stations

Five new central area stations were planned on the Picc-Vic line, including two low-level platforms at Piccadilly and Victoria stations.[1] Each would have been built on a tangent track and would have allowed trains of up to eight cars. There would have been escalators to the surface level, and lifts for disabled people. Customer information system and PA systems would be installed, along with CCTV to make high staffing levels unnecessary.

Victoria Low Level would have a concourse below Long Millgate, serving the Co-Operative HQ and the Corn Exchange. Development of the Picc-Vic would also allow the main line station to be rationalised and redeveloped, along with a proposed new bus station.

Market Street (or Royal Exchange) would have lain beneath the junction of Corporation Street, Cross Street, and Market Street, directly linking into the Royal Exchange, Marks & Spencer, as well as the Arndale Centre.

Albert Square/St. Peter's Square (or Central), serving the administrative and entertainment parts of the city, would have six entrances in St Peter's Square, together with a bus lay-by, part of a re-designed square. Albert Square would also be redesigned, with a concourse beneath the square, along with a direct link into the Heron House development and a travelator link to Oxford Road railway station.

Princess Street (or Whitworth) would have been built on the site of the present Whitworth House, with a direct link to the proposed major development north and east of the station, as well as serving the Manchester College site (formerly City College Manchester), UMIST, as well as other developments.

Piccadilly Low Level would be a side-platform station, built in a 'cut-and-cover' section, with a mezzanine level concourse. Escalators would take passengers to both the Picc-Vic and East-West platforms, along with a subway-escalator link to the mainline station concourse, and a direct link to a new 12-stand bus station, next to the new station. Victory House, a planned development by UMIST (now the University of Manchester), would also be served by the station.

Rolling stock

The initial publicity for the Picc-Vic plan, which was described as "Manchester's tube project", showed an artist's impression of a platform with a train resembling the 1967 Stock, as used on the Victoria line in London.[5] However, new trains were planned for the Picc-Vic line, designated as Class 316. This proposed type of rolling stock would have been derived from the "PEP" prototypes on the Southern Region, and would have formed part of the same family of EMUs as Class 313, 314, 315, 507 and 508. The planned twin bore tunnels were intended to be built with a diameter of 18 ft (5.5 m), large enough to accommodate both a main line train type, and the OHLE wires.[6]

Legacy

Projects at Bury Interchange, Altrincham Interchange, and Hazel Grove Branch electrification/improvement were completed, despite the overall scheme being abandoned. Metrolink, a light-rail system in Greater Manchester, was proposed in 1982 as a means to connect Manchester Piccadilly to Manchester Victoria; it opened in 1992. In 2008, over 30 years after the project was cancelled, prospects of an underground rail link under Manchester were revived by Transport Secretary and MP for Bolton West, Ruth Kelly, who announced a Department for Transport study of rail provision.[7] In the 2011 United Kingdom budget, it was announced that the Ordsall Chord would instead be constructed as an overground railway scheme designed to link Manchester Piccadilly and Manchester Victoria in a comparable fashion to Picc-Vic.[2][8] The chord opened to passengers in December 2017.[9]

In 2012 researchers from the Manchester School of Architecture at the University of Manchester conducted an investigation under the Arndale Centre in the city centre and discovered a long-forgotten subterranean void around 30 feet (9.1 m) below the surface. The void area had apparently been included in the construction of the shopping centre in the 1970s to enable a link to be built to a new Royal Exchange underground railway station when the planned Picc-Vic tunnel came into service.[3]

In 2019, in the publication Our Prospectus for Rail by regional mayor Andy Burnham, an underground tunnel through Manchester city centre was once again proposed.[10]

Further reading

- Picc-Vic Project, G.M.C., 1975, OCLC 644295614

References

- SELNEC PTE (October 1971), SELNEC Picc-Vic Line, SELNEC PTE publicity brochure

- "Consultation into Manchester rail link plans". BBC News. 7 October 2011.

- "Remains of Manchester tube system unearthed". University of Manchester. 13 March 2012. Archived from the original on 22 August 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- Donald T. Cross, M. Roger Bristow (1983). English Structure Planning. Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 0-85086-094-6.

- "From the archive, 18 July 1967: Green light for Manchester tube project". theguardian.com. The Guardian. 18 July 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- Brook, Richard; Dodge, Martin (2012). Infra_MANC (PDF). Cube Gallery/Manchester School of Architecture. p. 134. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- Salter, Alan (12 February 2008). "Rail tunnel vision revived". Manchester Evening News. M.E.N. Media. Retrieved 8 March 2009.

- "George Osborne confirms £85m Piccadilly - Victoria rail link in Budget". Manchester Evening News. M.E.N. Media. 23 March 2011.

- "£85m rail link opens in city centre". BBC News. 10 December 2017.

- "Greater Manchester rail masterplan launched". Railway Gazette. 30 September 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2019.