Central London Railway

The Central London Railway (CLR), also known as the Twopenny Tube, was a deep-level, underground "tube" railway[note 1] that opened in London in 1900. The CLR's tunnels and stations form the central section of the London Underground's Central line.

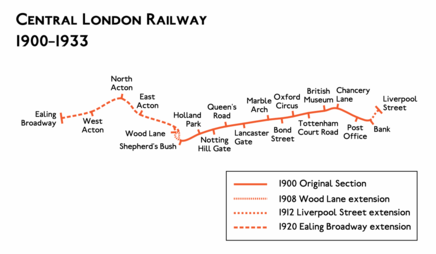

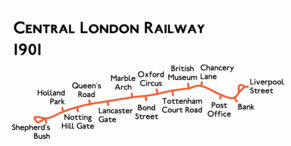

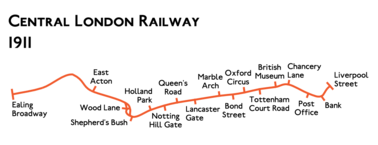

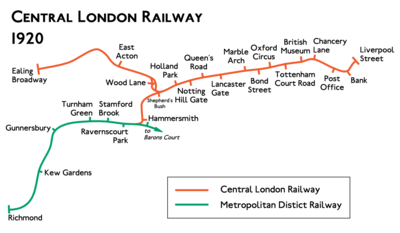

The railway company was established in 1889, funding for construction was obtained in 1895 through a syndicate of financiers and work took place from 1896 to 1900. When opened, the CLR served 13 stations and ran completely underground in a pair of tunnels for 9.14 kilometres (5.68 mi) between its western terminus at Shepherd's Bush and its eastern terminus at the Bank of England, with a depot and power station to the north of the western terminus.[1] After a rejected proposal to turn the line into a loop, it was extended at the western end to Wood Lane in 1908 and at the eastern end to Liverpool Street station in 1912. In 1920, it was extended along a Great Western Railway line to Ealing to serve a total distance of 17.57 kilometres (10.92 mi).[1]

After initially making good returns for investors, the CLR suffered a decline in passenger numbers due to increased competition from other underground railway lines and new motorised buses. In 1913, it was taken over by the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL), operator of the majority of London's underground railways. In 1933 the CLR was taken into public ownership along with the UERL.

Establishment

Origin, 1889–92

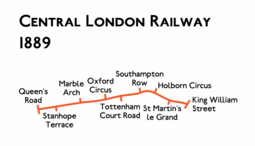

In November 1889, the CLR published a notice of a private bill that would be presented to Parliament for the 1890 parliamentary session.[2] The bill proposed an underground electric railway running from the junction of Queen's Road (now Queensway) and Bayswater Road in Bayswater to King William Street in the City of London with a connection to the then-under construction, City and South London Railway (C&SLR) at Arthur Street West. The CLR was to run in a pair of tunnels under Bayswater Road, Oxford Street, New Oxford Street, High Holborn, Holborn, Holborn Viaduct, Newgate Street, Cheapside, and Poultry. Stations were planned at Queen's Road, Stanhope Terrace, Marble Arch, Oxford Circus, Tottenham Court Road, Southampton Row, Holborn Circus, St. Martin's Le Grand and King William Street.[3]

The tunnels were to be 11 feet (3.35 m) in diameter, constructed with a tunnelling shield, and would be lined with cast iron segments. At stations, the tunnel diameter would be 22 feet (6.71 m) or 29 feet (8.84 m) depending on layout. A depot and power station were to be constructed on a 1.5-acre (0.61 ha) site on the west side of Queen's Road. Hydraulic lifts from the street to the platforms were to be provided at each station.[4]

The proposals faced strong objections from the Metropolitan and District Railways (MR and DR) whose routes on the Inner Circle,[note 2] to the north and the south respectively, the CLR route paralleled; and from which the new line was expected to take passengers. The City Corporation also objected, concerned about potential damage to buildings close to the route caused by subsidence as was experienced during the construction of the C&SLR. The Dean and Chapter of St Paul's Cathedral objected, concerned about the risks of undermining the cathedral's foundations. Sir Joseph Bazalgette objected that the tunnels would damage the city's sewer system. The bill was approved by the House of Commons, but was rejected by the House of Lords, which recommended that any decision be postponed until after the C&SLR had opened and its operation could be assessed.[5]

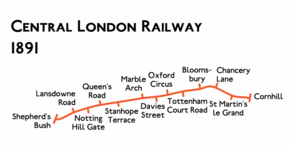

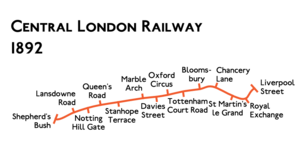

In November 1890, with the C&SLR about to start operating, the CLR announced a new bill for the 1891 parliamentary session.[6] The route was extended at the western end to run under Notting Hill High Street (now Notting Hill Gate) and Holland Park Avenue to end at the eastern corner of Shepherd's Bush Green, with the depot and power station site relocated to be north of the terminus on the east side of Wood Lane. The westward extension of the route was inspired by the route of abandoned plans for the London Central Subway, a sub-surface railway that was briefly proposed in early 1890 to run directly below the roadway on a similar route to the CLR.[7] The eastern terminus was changed to Cornhill and the proposed Southampton Row station was replaced by one in Bloomsbury. Intermediate stations were added at Lansdowne Road, Notting Hill Gate, Davies Street (which the CLR planned to extend northwards to meet Oxford Street) and at Chancery Lane.[8] The earlier plan to connect to the C&SLR was dropped and the diameter of the CLR's tunnels was increased to 11 feet 6 inches (3.51 m).[7] This time the bill was approved by both Houses of Parliament and received Royal Assent on 5 August 1891 as the Central London Railway Act, 1891.[9] In November 1891, the CLR publicised another bill. The eastern end of the line was re-routed north-east and extended to end under the Great Eastern Railway's (GER's) terminus at Liverpool Street station with the Cornhill terminus dropped and a new station proposed at the Royal Exchange.[10] The proposals received assent as the Central London Railway Act, 1892 on 28 June 1892.[11]

The money to build the CLR was obtained through a syndicate of financiers including Ernest Cassel, Henry Oppenheim, Darius Ogden Mills, and members of the Rothschild family.[12] On 22 March 1894, the syndicate incorporated a contractor to construct the railway, the Electric Traction Company Limited (ETCL), which agreed a construction cost of £2,544,000 (approximately £292 million today)[13] plus £700,000 in 4 per cent debenture stock.[14] When the syndicate offered 285,000 CLR company shares for sale at £10 each in June 1895,[14] only 14 per cent was bought by the British public, which was cautious of such investments following failures of similar railway schemes.[15] Some shares were sold in Europe and the United States, but the unsold remainder was bought by members of the syndicate or by the ETCL.[14]

Construction, 1896–1900

To design the railway, the CLR employed the engineers James Henry Greathead, Sir John Fowler, and Sir Benjamin Baker.[8] Greathead had been the engineer for the Tower Subway and the C&SLR, and had developed the tunnelling shield used to excavate those companies' tunnels under the River Thames. Fowler had been the engineer on the Metropolitan Railway, the world's first underground railway opened in 1863, and Baker had worked on New York's elevated railways and on the Forth Railway Bridge with Fowler. Greathead died shortly after work began and was replaced by Basil Mott, his assistant during the construction of the C&SLR.[8]

Like most legislation of its kind, the act of 1891 imposed a time limit for the compulsory purchase of land and the raising of capital.[note 3] The original date specified for completion of construction was the end of 1896, but the time required to raise the finance and purchase station sites meant that construction had not begun by the start of that year. To give itself extra time, the CLR had obtained an extension of time to 1899 by the Central London Railway Act, 1894.[16][17] Construction works were let by the ETCL as three sub-contracts: Shepherd's Bush to Marble Arch, Marble Arch to St Martin's Le Grand and St Martin's Le Grand to Bank. Work began with demolition of buildings at the Chancery Lane site in April 1896 and construction shafts were started at Chancery Lane, Shepherd's Bush, Stanhope Terrace and Bloomsbury in August and September 1896.[18]

Negotiations with the GER for the works under Liverpool Street station were unsuccessful, and the final section beyond Bank was only constructed for a short distance as sidings. To minimise the risk of subsidence, the routing of the tunnels followed the roads on the surface and avoided passing under buildings. Usually the tunnels were bored side by side 60–110 feet (18–34 m) below the surface, but where a road was too narrow to allow this, the tunnels were aligned one above the other, so that a number of stations have platforms at different levels.[19] To assist with the deceleration of trains arriving at stations and the acceleration of trains leaving, station tunnels were located at the tops of slight inclines.[20]

Tunnelling was completed by the end of 1898,[21] and, because a planned concrete lining to the cast iron tunnel rings was not installed, the internal diameter of the tunnels was generally 11 feet 8.25 inches (3.56 m).[19] For Bank station, the CLR negotiated permission with the City Corporation to construct its ticket hall beneath a steel framework under the roadway and pavements at the junction of Threadneedle Street and Cornhill. This involved diverting pipework and cables into ducts beneath the subways linking the ticket hall to the street.[19] Delays on this work were so costly that they nearly bankrupted the company.[18] A further extension of time to 1900 was obtained through the Central London Railway Act, 1899.[16][22]

Apart from Bank, which was completely below ground, all stations had buildings designed by Harry Bell Measures. They were single-storey structures to allow for future commercial development above and had elevations faced in beige terracotta. Each station had lifts manufactured by the Sprague Electric Company in New York. The lifts were provided in a variety of sizes and configurations to suit the passenger flow at each station. Generally they operated in sets of two or three in a shared shaft.[23] Station tunnel walls were finished in plain white ceramic tiles and lit by electric arc lamps.[24] The electricity to run the trains and the stations was supplied from the power station at Wood Lane at 5,000V AC which was converted at sub-stations along the route to 550V DC to power the trains via a third rail system.[25]

Opening

_Railway_Poster%2C_1905.png)

The official opening of the CLR by the Prince of Wales took place on 27 June 1900, one day before the time limit of the 1899 Act,[16] although the line did not open to the public until 30 July 1900.[25][note 4] The railway had stations at:[27]

- Shepherd's Bush

- Holland Park

- Notting Hill Gate

- Queen's Road (now Queensway)[27]

- Lancaster Gate

- Marble Arch

- Bond Street (opened 24 September 1900)[27]

- Oxford Circus

- Tottenham Court Road

- British Museum (closed 1933)[27]

- Chancery Lane

- Post Office (now St. Paul's)[27]

- Bank

The CLR charged a flat fare of two pence for a journey between any two stations, leading the Daily Mail to give the railway the nickname of the Twopenny Tube in August 1900.[28] The service was very popular, and, by the end of 1900, the railway had carried 14,916,922 passengers.[29] By attracting passengers from the bus services along its route and from the slower, steam-hauled, MR and DR services, the CLR achieved passenger numbers around 45 million per year in the first few years of operation,[28] generating a high turnover that was more than twice the expenses. From 1900 to 1905, the company paid a dividend of 4 per cent to investors.[30]

Rolling stock

Greathead had originally planned for the trains to be hauled by a pair of small electric locomotives, one at each end of a train, but the Board of Trade rejected this proposal and a larger locomotive was designed which was able to pull up to seven carriages on its own. Twenty-eight locomotives were manufactured in America by the General Electric Company (of which syndicate member Darius Ogden Mills was a director) and assembled in the Wood Lane depot.[31][note 5] A fleet of 168 carriages was manufactured by the Ashbury Railway Carriage and Iron Company and the Brush Electrical Engineering Company. Passengers boarded and left the trains through folding lattice gates at each end of the carriages; these gates were operated by guards who rode on an outside platform.[32][note 6] The CLR had originally intended to have two classes of travel, but dropped the plan before opening, although its carriages were built with different qualities of interior fittings for this purpose.[31]

Soon after the railway opened, complaints about vibrations from passing trains began to be made by occupiers of buildings along the route. The vibrations were caused by the heavy, largely unsprung locomotives which weighed 44 tons (44.7 tonnes). The Board of Trade set up a committee to investigate the problem, and the CLR experimented with two solutions. For the first solution, three locomotives were modified to use lighter motors and were provided with improved suspension, so the weight was reduced to 31 tons (31.5 tonnes), more of which was sprung to reduce vibrations; for the second solution, two six-carriage trains were formed that had the two end carriages converted and provided with driver's cabs and their own motors so they could run as multiple units without a separate locomotive. The lighter locomotives did reduce the vibrations felt at the surface, but the multiple units removed it almost completely and the CLR chose to adopt that solution. The committee's report, published in 1902,[34] also found that the CLR's choice of 100 lb/yard (49.60 kg/m) bridge rail for its tracks rather than a stiffer bullhead rail on cross sleepers contributed to the vibration.[35]

Following the report, the CLR purchased 64 driving motor carriages for use with the existing stock; together, these were formed into six- or seven-carriage trains. The change to multiple unit operation was completed by June 1903 and all but two of the locomotives were scrapped. Those two were retained for shunting use in the depot.[36]

Extensions

Reversing loops, 1901

The CLR's ability to manage its high passenger numbers was constrained by the service interval that it could achieve between trains. This was directly related to the time taken to turn around trains at the termini. At the end of a journey, a locomotive had to be disconnected from the leading end of the train and run around to the rear, where it was reconnected before proceeding in the opposite direction; an exercise that took a minimum of 2½ minutes.[37] Seeking to shorten this interval, the CLR published a bill in November 1900 for the 1901 parliamentary session.[38] The bill requested permission to construct loops at each end of the line so that trains could be turned around without disconnecting the locomotive. The loop at the western end was planned to run anti-clockwise under the three sides of Shepherd's Bush Green. For the eastern loop the alternatives were a loop under Liverpool Street station or a larger loop running under Threadneedle Street, Old Broad Street, Liverpool Street, Bishopsgate and returning to Threadneedle Street. The estimated cost of the loops was £800,000 (approximately £87.2 million today),[13] most of which was for the eastern loop with its costly wayleaves.[37]

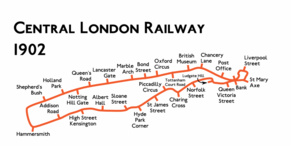

The CLR bill was one of more than a dozen tube railway bills submitted to Parliament for the 1901 session,[note 7] To review the bills on an equal basis, Parliament established a joint committee under Lord Windsor,[40] but by the time the committee had produced its report, the parliamentary session was almost over and the promoters of the bills were asked to resubmit them for the following 1902 session. Among the committee's recommendations were the withdrawal of the CLR's City loop,[41] and that a quick, tube route from Hammersmith to the City of London would benefit London's commuters.[42][note 8]

Loop line, 1902–05

Rather than resubmit its 1901 bill, the CLR presented a much more ambitious alternative for the 1902 parliamentary session. The reversing loops were dropped, and the CLR instead proposed to turn the whole railway into a single large loop by constructing a new southern route between the two existing end points, adopting the committee's recommendation for a Hammersmith to City route.[43][44] At the western end, new tunnels were to be extended from the dead-end reversing siding west of Shepherd's Bush station and from the depot access tunnel. The route was to pass under Shepherd's Bush Green and run under Goldhawk Road as far as Hammersmith Grove where it was to turn south. At the southern end of Hammersmith Grove a station was to be provided on the corner of Brook Green Road (now Shepherd's Bush Road) to provide an interchange with the three stations already located there.[43][note 9]

From Hammersmith, the CLR's route was to turn eastwards and run under Hammersmith Road and Kensington High Street with interchange stations at the DR's Addison Road (now Kensington Olympia) and High Street Kensington stations. From Kensington High Street, the route was to run along the south side of Kensington Gardens beneath Kensington Road, Kensington Gore and Knightsbridge. Stations were to be constructed at the Royal Albert Hall and the junction of Knightsbridge and Sloane Street, where the Brompton & Piccadilly Circus Railway (B&PCR) already had permission to build a station.[note 10] From Sloane Street, the CLR's proposed route ran below that approved for the B&PCR under the eastern portion of Knightsbridge, under Hyde Park Corner and along Piccadilly to Piccadilly Circus. At Hyde Park Corner, a CLR station was to be sited close to the B&PCR's station and the CLR's next station at St James's Street was a short distance to the east of the B&PCR's planned Dover Street station. At Piccadilly Circus, the CLR planned an interchange with the partially completed station of the stalled Baker Street and Waterloo Railway. The CLR route was then to turn south-east beneath Leicester Square to a station at Charing Cross and then north-east under Strand to Norfolk Street to interchange with the planned terminus of the Great Northern & Strand Railway.[43][note 10]

The route was then to continue east under Fleet Street to Ludgate Circus for an interchange with the South Eastern and Chatham Railway's (SECR's) Ludgate Hill station, then south under New Bridge Street, and east into Queen Victoria Street where a station was planned to connect to the District Railway's Mansion House station. The route was then to continue under Queen Victoria Street to reach the CLR's station at Bank, where separate platforms below the existing ones were to be provided. The final section of the route developed on the proposed loop from the year before with tunnels winding under the City's narrow, twisting streets. The tunnels were to run east, one below the other, beneath Cornhill and Leadenhall Street, north under St Mary Axe and west to Liverpool Street station, then south under Blomfield Street, east under Great Winchester Street, south under Austin Friars and Old Broad Street and west under Threadneedle Street where the tunnels were to connect with the existing sidings back into Bank. Two stations were to be provided on the loop; at the south end of St Mary Axe and at Liverpool Street station.[43] To accommodate the additional rolling stock needed to operate the longer line, the depot was to be extended northwards. The power station was also to be enlarged to increase the electricity supply.[45] The CLR estimated that its plan would cost £3,781,000 (approximately £414 million today):[13] £2,110,000 for construction, £873,000 for land and £798,000 for electrical equipment and trains.[45]

The CLR bill was one of many presented for the 1902 parliamentary session (including several for the Hammersmith to City route) and it was examined by another joint committee under Lord Windsor.[note 11] The proposal received support from the mainline railway companies the route interchanged with and from the C&SLR, which had a station at Bank. The London County Council and the City Corporation also supported the plan. The Metropolitan Railway opposed, seeing further competition to its services on the Inner Circle. Questions were raised in Parliament about the safety of tunnelling so close to the vaults of many City banks and the risk that subsidence might cause vault doors to jam shut. Another concern was the danger of undermining the foundations of the Dutch Church in Austin Friars. The Windsor committee rejected the section between Shepherd's Bush and Bank, preferring a competing route from the J. P. Morgan-backed Piccadilly, City and North East London Railway (PC&NELR).[47] Without the main part of its new route, the CLR withdrew the City loop, leaving a few improvements to the existing line to be approved in the Central London Railway Act, 1902 on 31 July 1902.[45][48]

In late 1902, the PC&NELR plans collapsed after a falling out between the scheme's promoters led to a crucial part of the planned route coming under the control of a rival, the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL), which withdrew it from parliamentary consideration.[49] With the PC&NELR scheme out of the way, the CLR resubmitted its bill in 1903,[50][51] although consideration was again held up by Parliament's establishment of the Royal Commission on London Traffic tasked to assess the manner in which transport in London should be developed.[52] While the Commission deliberated, any review of bills for new lines and extensions was postponed, so the CLR withdrew the bill.[50] The CLR briefly re-presented the bill for the 1905 parliamentary session but withdrew it again, before making an agreement with the UERL in October 1905 that neither company would submit a bill for an east–west route in 1906.[53] The plan was then dropped as the new trains with driving positions at both ends made it possible for the CLR to reduce the minimum interval between trains to two minutes without building the loop.[36]

Wood Lane, 1906–08

In 1905, the government announced plans to hold an international exhibition to celebrate the Entente cordiale signed by France and Britain in 1904. The location of the Franco-British Exhibition's White City site was across Wood Lane from the CLR's depot.[54] To exploit the opportunity to carry visitors to the exhibition, the CLR announced a bill in November 1906 seeking to create a loop from Shepherd's Bush station and back, on which a new Wood Lane station close to the exhibition's entrance would be built.[55] The new work was approved on 26 July 1907 in the Central London Railway Act, 1907.[56]

The new loop was formed by constructing a section of tunnel joining the end of the dead-end reversing tunnel to the west of Shepherd's Bush station and the north side of the depot. From Shepherd's Bush, trains ran anti-clockwise around the single track loop, first through the original depot access tunnel, then passed the north side of the depot and through the new station before entering the new section of tunnel and returning to Shepherd's Bush. Changes were also made to the depot layout to accommodate the new station and the new looped operations. Construction work on the exhibition site had started in January 1907, and the exhibition and new station opened on 14 May 1908. The station was on the surface between the two tunnel openings and was a basic design by Harry Bell Measures. It had platforms both sides of the curving track – passengers alighted on to one and boarded from the other (an arrangement now known as the Spanish solution).[54]

Liverpool Street, 1908–12

With the extension to Wood Lane operational, the CLR revisited its earlier plan for an eastward extension from Bank to Liverpool Street station. This time, the Great Eastern Railway (GER) agreed to allow the CLR to build a station under its own main line terminus, provided that no further extension would be made north or north-east from there – territory served by the GER's routes from Liverpool Street.[57] A bill was announced in November 1908,[58] for the 1909 parliamentary session and received Royal Assent as the Central London Railway Act, 1909 on 16 August 1909.[57][59] Construction started in July 1910 and the new Liverpool Street station was opened on 28 July 1912.[57] Following their successful introduction at the DR's Earl's Court station in 1911, the station was the first underground station in London to be built with escalators. Four were provided, two to Liverpool Street station and two to the North London Railway's adjacent Broad Street station.[60]

Ealing Broadway, 1911–20

The CLR's next planned extension was westward to Ealing. In 1905, the Great Western Railway (GWR) had obtained parliamentary approval to construct the Ealing and Shepherd's Bush Railway (E&SBR), connecting its main line route at Ealing Broadway to the West London Railway (WLR) north of Shepherd's Bush.[61] From Ealing, the new line was to curve north-east through still mostly rural North Acton, then run east for a short distance parallel with the GWR's High Wycombe line, before curving south-east. The line was then to run on an embankment south of Old Oak Common and Wormwood Scrubs before connecting to the WLR a short distance to the north of the CLR's depot.[62]

Construction work did not begin immediately, and, in 1911, the CLR and GWR agreed running powers for CLR services over the line to Ealing Broadway. To make a connection to the E&SBR, the CLR obtained parliamentary permission for a short extension northward from Wood Lane station on 18 August 1911 in the Central London Railway Act, 1911.[61][63] The new E&SBR line was constructed by the GWR and opened as a steam-hauled freight only line on 16 April 1917. Electrification of the track and the start of CLR services were postponed until after the end of World War I, not starting until 3 August 1920 when a single intermediate station at East Acton was also opened.[64][27]

Wood Lane station was modified and extended to accommodate the northward extension tracks linking to the E&SBR. The existing platforms on the loop were retained, continuing to be used by trains that were turning back to central London, and two new platforms for trains running to or from Ealing were constructed at a lower level on the new tracks, which connected to each side of the loop. Ealing Broadway station was modified to provide additional platforms for CLR use between the existing but separate sets of platforms used by the GWR and the DR.[62]

To provide services over the 6.97-kilometre (4.33 mi) extension, the CLR ordered 24 additional driving motor carriages from the Brush Company, which, when delivered in 1917, were first borrowed by the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway for use in place of carriages ordered for its extension to Watford Junction. The new carriages were the first for tube-sized trains that were fully enclosed, without gated platforms at the rear, and were provided with hinged doors in the sides to speed-up passenger loading times. To operate with the new stock the CLR converted 48 existing carriages, providing a total of 72 carriages for twelve six-car trains. Modifications made while in use on the Watford extension meant that the new carriages were not compatible with the rest of the CLR's fleet and they became known as the Ealing stock.[65]

The E&SBR remained part of the GWR until nationalisation at the beginning of 1948, when (with the exception of Ealing Broadway station) it was transferred to the London Transport Executive. Ealing Broadway remained part of British Railways, as successors to the GWR.[66]

Richmond, 1913 and 1920

In November 1912,[67] the CLR announced plans for an extension from Shepherd's Bush on a new south-westwards route. Tunnels were planned under Goldhawk Road, Stamford Brook Road and Bath Road to Chiswick Common where a turn to the south would take the tunnels under Turnham Green Terrace for a short distance. The route then was to head west again to continue under Chiswick High Road before coming to the surface east of the London and South Western Railway's (L&SWR's) Gunnersbury station. Here a connection would be made to allow the CLR's tube trains to run south-west to Richmond station over L&SWR tracks that the DR shared and had electrified in 1905. Stations were planned on Goldhawk Road at its junctions with The Grove, Paddenswick Road and Rylett Road, at Emlyn Road on Stamford Brook Road, at Turnham Green Terrace (for a connection with the L&SWR's/DR's Turnham Green station) and at the junction of Chiswick High Road and Heathfield Terrace. Beyond Richmond, the CLR saw further opportunities to continue over L&SWR tracks to the commuter towns of Twickenham, Sunbury and Shepperton, although this required the tracks to be electrified.[68] The CLR received permission for the new line to Gunnersbury on 15 August 1913 in the Central London Railway Act, 1913,[69] but World War I prevented the works from commencing and the permission expired.[68]

In November 1919,[70] the CLR published a new bill to revive the Richmond extension, but using a different route that required only a short section of new tunnel construction. The new proposal was to construct tunnels southwards from Shepherd's Bush station, which would come to the surface to connect to disused L&SWR tracks north of Hammersmith Grove Road station that had closed in 1916. From Hammersmith, the disused LS&WR tracks continued westwards, on the same viaduct as the DR's tracks through Turnham Green to Gunnersbury and Richmond.[note 12] The plan required electrification of the disused tracks, but avoided the need for costly tunnelling and would have shared the existing stations on the route with the DR. The plan received assent on 4 August 1920 as part of the Central London and Metropolitan District Railway Companies (Works) Act, 1920,[72] although the CLR made no attempt to carry out any of the work. The disused L&SWR tracks between Ravenscourt Park and Turnham Green were eventually used for the westward extension of the Piccadilly line from Hammersmith in 1932.[73]

Competition, co-operation and sale, 1906–13

From 1906 the CLR began to experience a large fall in passenger numbers[note 13] caused by increased competition from the DR and the MR, which electrified the Inner Circle in 1905, and from the Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway (GNP&BR) which opened its rival route to Hammersmith in 1906. Road traffic also offered a greater challenge as motor buses began replacing the horse drawn variety in greater numbers. In an attempt to maintain income, the company increased the flat fare for longer journeys to three pence in July 1907 and reduced the fare for shorter journeys to one penny in March 1909. Multiple booklets of tickets, which had previously been sold at face value, were offered at discounts,[note 14] and season tickets were introduced from July 1911.[57]

The CLR looked to economise through the use of technological developments. The introduction in 1909 of dead-man's handles to the driver controls and "trip cocks" devices on signals and trains meant that the assistant driver was no longer required as a safety measure.[75] Signalling automation allowed the closure of many of the line's 16 signal boxes and a reduction in signalling staff.[76] From 1911, the CLR operated a parcel service, making modifications to the driving cars of four trains to provide a compartment in which parcels could be sorted. These were collected at each station and distributed to their destinations by a team of tricycle riding delivery boys. The service made a small profit, but ended in 1917 because of wartime labour shortages.[77]

The problem of declining revenues was not limited to the CLR; all of London's tube lines and the sub-surface DR and MR were affected by competition to some degree. The reduced income from the lower passenger numbers made it difficult for the companies to pay back borrowed capital, or to pay dividends to shareholders.[78] The CLR's dividend payments fell to 3 per cent from 1905, but those of the UERL's lines were as low as 0.75 per cent.[79] From 1907, the CLR, the UERL, the C&SLR, and the Great Northern & City Railway companies began to introduce fare agreements. From 1908, they began to present themselves through common branding as the Underground.[78] In November 1912, after secret take-over talks, the UERL announced that it was purchasing the CLR, swapping one of its own shares for each of the CLR's.[80][note 15] The take-over took effect on 1 January 1913, although the CLR company remained legally separate from the UERL's other tube lines.[61]

Improvements and integration, 1920–33

Central London Railway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Extent of railway at transfer to LPTB, 1933 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Following the takeover, the UERL took steps to integrate the CLR's operations with its own. The CLR's power station was closed in March 1928 with power instead being supplied from the UERL's Lots Road Power Station in Chelsea. Busier stations were modernised; Bank and Shepherd's Bush stations received escalators in 1924, Tottenham Court Road and Oxford Circus in 1925 and Bond Street in 1926, which also received a new entrance designed by Charles Holden.[81][82] Chancery Lane and Marble Arch stations were also rebuilt to receive escalators in the early 1930s.[82]

On 5 November 1923 new stations were opened on the Ealing extension at North Acton and West Acton.[27] They were built to serve residential and industrial developments around Park Royal and, like East Acton, the station buildings were basic structures with simple timber shelters on the platforms.[62] The poor location of British Museum station and the lack of an interchange with the GNP&BR's station at Holborn had been a considered a problem by the CLR almost since the opening of the GNP&BR in 1906. A pedestrian subway to link the stations was considered in 1907, but not carried out.[83] A proposal to enlarge the tunnels under High Holborn to create new platforms at Holborn station for the CLR and to abandon British Museum station was included in a CLR bill submitted to parliament in November 1913.[84] This was given assent in 1914, but World War I prevented any works taking place, and it was not until 1930 that the UERL revived the powers and began construction work. The new platforms, along with a new ticket hall and escalators to both lines, opened on 25 September 1933, British Museum station having closed at the end of traffic the day before.[27][83]

Between March 1926 and September 1928, the CLR converted the remaining gate stock carriages in phases. The end platforms were enclosed to provide additional passenger accommodation and two sliding doors were inserting in each side. The conversions increased capacity and allowed the CLR to remove gatemen from the train crews, with responsibility for controlling doors moving to the two guards who each managed half the train. Finally, the introduction of driver/guard communications in 1928 allowed the CLR to dispense with the second guard, reducing a train crew to just a driver and a guard.[85] The addition of doors in the sides of cars caused problems at Wood Lane where the length of the platform on the inside of the returning curve was limited by an adjacent access track into the depot. The problem was solved by the introduction of a pivoted section of platform which usually sat above the access track and allowed passengers to board trains as normal, but which could be moved to allow access to the depot.[86]

Move to public ownership, 1923–33

Despite closer co-operation and improvements made to the CLR stations and to other parts of the network,[note 16] the Underground railways continued to struggle financially. The UERL's ownership of the highly profitable London General Omnibus Company (LGOC) since 1912 had enabled the UERL group, through the pooling of revenues, to use profits from the bus company to subsidise the less profitable railways.[note 17] However, competition from numerous small bus companies during the early 1920s eroded the profitability of the LGOC and had a negative impact on the profitability of the whole UERL group.[87]

To protect the UERL group's income, its chairman Lord Ashfield lobbied the government for regulation of transport services in the London area. Starting in 1923, a series of legislative initiatives were made in this direction, with Ashfield and Labour London County Councillor (later MP and Minister of Transport) Herbert Morrison, at the forefront of debates as to the level of regulation and public control under which transport services should be brought. Ashfield aimed for regulation that would give the UERL group protection from competition and allow it to take substantive control of the LCC's tram system; Morrison preferred full public ownership.[88] After seven years of false starts, a bill was announced at the end of 1930 for the formation of the London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB), a public corporation that would take control of the UERL, the MR and all bus and tram operators within an area designated as the London Passenger Transport Area.[89] The Board was a compromise – public ownership but not full nationalisation – and came into existence on 1 July 1933. On this date, ownership of the assets of the CLR and the other Underground companies transferred to the LPTB.[90][note 18]

Legacy

- For a history of the line after 1933 see Central line

In 1935 the LPTB announced plans as part of its New Works Programme to extend the CLR at both ends by taking over and electrifying local routes owned by the GWR in Middlesex and Buckinghamshire and by the LNER in east London and Essex. Work in the tunnels to lengthen platforms for longer trains and to correct misaligned tunnel sections that slowed running speeds was also carried out. A new station was planned to replace the cramped Wood Lane.[91] The service from North Acton through Greenford and Ruislip to Denham was due to open between January 1940 and March 1941. The eastern extension from Liverpool Street to Stratford, Leyton and Newbury Park and the connection to the LNER lines to Hainault, Epping and Ongar were intended to open in 1940 and 1941.[92] World War II caused works on both extensions to be halted and London Underground services were extended in stages from 1946 to 1949,[27] although the final section from West Ruislip to Denham was cancelled.[93] Following the LPTB takeover, the Harry Beck-designed tube map began to show the route's name as the "Central London Line" instead of "Central London Railway".[94] In anticipation of the extensions taking its services far beyond the boundaries of the County of London, "London" was omitted from the name on 23 August 1937; thereafter it was simply the "Central line".[95][94] The CLR's original tunnels form the core of the Central line's 72.17-kilometre (44.84 mi) route.[1]

During World War II, 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) of completed tube tunnels built for the eastern extension between Gants Hill and Redbridge were used as a factory by Plessey to manufacture electronic parts for aircraft.[96] Other completed tunnels were used as air-raid shelters at Liverpool Street, Bethnal Green and between Stratford and Leyton,[97] as were the closed parts of British Museum station[98] At Chancery Lane, new tunnels 16 feet 6 inches (5.03 m) in diameter and 1,200 feet (370 m) long were constructed below the running tunnels during 1941 and early 1942. These were fitted out as a deep level shelter for government use as a protected communications centre.[99] Work on a similar shelter was planned at Post Office station (renamed St Paul's in 1937) but was cancelled; the lift shafts that were made redundant when the station was given escalators in January 1939 were converted for use as a protected control centre for the Central Electricity Board.[100]

See also

- Horace Field Parshall, chairman and designer of the line's electrical distribution system

Notes and references

Notes

- A "tube" railway is an underground railway constructed in a cylindrical tunnel by the use of a tunnelling shield, usually deep below ground level. Contrast "cut and cover" tunnelling.

- The Inner Circle (now the Circle line) was a sub-surface loop line operated jointly by the MR and the DR.

- Time limits were included in such legislation to encourage the railway company to complete the construction of its line as quickly as possible. They also prevented unused permissions acting as an indefinite block to other proposals.

- A commemorative plaque of the opening was installed at Bank station and listed the directors as Sir Henry Oakley (chairman), Lord Colville of Culross, Sir Francis Knollys, Algernon H Mills, Lord Rathmore and Henry Tennant.[26]

- After arriving at the London Docks, the locomotives were taken along the river by barge to Chelsea and from there to the depot. One of the barges sank on the way, but the disassembled locomotive was salvaged and was put into use with the others.[31]

- A train originally required a crew of eight to operate: driver and assistant, front and rear guards and four gatemen.[33]

- In addition to bills for extensions to existing tube railways, bills for seven new tube railways were submitted to Parliament in 1901.[39] While a number received Royal Assent, none were built.

- The MR and the DR both offered services from Hammersmith to the City of London. The MR route ran via Paddington and the northern section of the Inner Circle and the DR route ran via Earl's Court and the southern section of the Inner Circle. The steam-hauled trains were slow and suffered from having to compete for track space in timetables crowded with services from the companies' other routes. The prospect of quick electric tube trains offered an attractive alternative.

- In 1901, the DR, MR and the London and South Western Railway (L&SWR) all had stations at Hammersmith, although the L&SWR's closed in 1916.

- The Brompton & Piccadilly Circus Railway and the Great Northern & Strand Railway merged in 1902 to form the Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway, forerunner of today's Piccadilly line.

- The Windsor committee examined bills for tube railways on an east–west alignment, and a separate committee under Lord Ribblesdale examined bills for tube railways on a north–south alignment.[46]

- The viaduct had been widened in 1911 to separate the DR's electric services to Richmond, Hounslow, Ealing and Uxbridge from the L&SWR's steam-hauled services, although the DR's trains had so out-competed the L&SWR's that it withdrew its own services in 1916. The viaduct and both sets of tracks were owned by the L&SWR.[71]

- In 1906 the CLR carried 43,057,997 passengers. In 1907 the number carried was 14 per cent lower at 36,907,491. The Franco-British Exhibition boosted numbers in 1908, but they fell back again afterwards and were still at around 36 million in 1912.[57][74]

- From July 1907, a twelve ticket strip of 3d tickets was sold at 2s 9d, a 3d discount, and twelve ticket strips of 2d tickets were sold at 1s 10d, a 2d discount, from November 1908.[57]

- At the same time, the UERL also bought the C&SLR, swapping two of its shares for three of the C&SLR's, reflecting the latter company's weaker financial condition.[80]

- The Bakerloo line extension to Watford Junction opened in 1917, the CCE&HR extension to Edgware opened in 1923/24 and the CS&LR extension to Morden opened in 1926.[27]

- By having a virtual monopoly of bus services, the LGOC was able to make large profits and pay dividends far higher than the underground railways ever had. In 1911, the year before its take over by the UERL, the dividend had been 18 per cent.[74]

- The CLR company continued in existence as a repository for all of the fractions of shares in the new LPTB that could not be distributed to the old companies' shareholders and to enable payment of interest on a CLR deed from 1912 owing to the bank Glyn, Mills & Co. The company was liquidated on 10 March 1939.[83]

References

- Length of line calculated from distances given at "Clive's Underground Line Guides, Central line, Layout". Clive D. W. Feathers. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- "No. 25996". The London Gazette. 26 November 1889. pp. 6640–6642.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 43.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 44.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 44–45.

- "No. 26109". The London Gazette. 25 November 1890. pp. 6570–6572.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 47.

- Day & Reed 2008, p. 52.

- "No. 26190". The London Gazette. 7 August 1891. p. 4245.

- "No. 26227". The London Gazette. 27 November 1891. pp. 6506–6507.

- "No. 26303". The London Gazette. 1 July 1892. pp. 3810–3811.

- Wolmar 2005, pp. 147–148.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 5.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 147.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 7.

- "No. 26529". The London Gazette. 6 July 1894. p. 3872.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 6.

- Day & Reed 2008, pp. 52–54.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 148.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 149.

- "No. 27105". The London Gazette. 4 August 1899. pp. 4833–4834.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 14.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 13.

- Day & Reed 2008, p. 56.

- "Photograph 1998/41282". London Transport Museum. Transport for London. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- Rose 1999.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 154.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 9.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 156.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 10.

- Day & Reed 2008, p. 54.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 18.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 91.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 15.

- Day & Reed 2008, pp. 57–58.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 94.

- "No. 27249". The London Gazette (Supplement). 23 November 1900. pp. 7666–7668.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 92.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 93.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 110–111.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 129.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 148–49.

- "No. 27379". The London Gazette. 22 November 1901. pp. 7776–7779.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 150.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 131.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 185.

- "No. 27460". The London Gazette. 1 August 1902. p. 4961.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 190–95.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 212.

- "No. 27498". The London Gazette. 25 November 1902. pp. 8001–8004.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 222.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 19.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 20.

- "No. 27971". The London Gazette. 27 November 1906. pp. 8361–8363.

- "No. 28044". The London Gazette. 26 July 1907. p. 5117.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 22.

- "No. 28200". The London Gazette. 27 November 1908. pp. 9088–9090.

- "No. 28280". The London Gazette. 17 August 1909. pp. 6261–6262.

- Day & Reed 2008, pp. 59 and 81.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 25.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 28.

- "No. 28524". The London Gazette. 22 August 1911. pp. 6216–6217.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 26.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, pp. 28–29.

- Day & Reed 2008, p. 150.

- "No. 28666". The London Gazette. 26 November 1912. pp. 9018–9020.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 273–274.

- "No. 28747". The London Gazette. 19 August 1913. pp. 5929–5931.

- "No. 31656". The London Gazette. 25 November 1919. pp. 14425–14429.

- Horne 2006, pp. 48 and 55.

- "No. 32009". The London Gazette. 6 August 1920. pp. 8171–8172.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 30.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 204.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 23.

- Day & Reed 2008, p. 59.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 24.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 282–283.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 203.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 205.

- Day & Reed 2008, p. 93.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 33.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 35.

- "No. 28776". The London Gazette. 25 November 1913. pp. 8539–8541.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, pp. 30 and 33.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 34.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 259.

- Wolmar 2005, pp. 259–262.

- "No. 33668". The London Gazette. 9 December 1930. pp. 7905–7907.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 266.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, pp. 37–38.

- Bruce & Croome 2006, p. 44.

- Wolmar 2005, p. 294.

- Lee 1970, p. 27.

- "London Tubes' New Names – Northern And Central lines". The Times (47772). 25 August 1937. p. 12. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- Emmerson & Beard 2004, pp. 108–121.

- Emmerson & Beard 2004, pp. 60–66.

- Connor 2006, p. 42.

- Emmerson & Beard 2004, pp. 30–37.

- Emmerson & Beard 2004, pp. 104–107.

Bibliography

- Badsey-Ellis, Antony (2005). London's Lost Tube Schemes. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-293-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bruce, J Graeme; Croome, Desmond F (2006) [1996]. The Central Line. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-297-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Connor, J E (2006) [1999]. London's Disused Underground Stations. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-250-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Day, John R; Reed, John (2008) [1963]. The Story of London's Underground. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-316-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Emmerson, Andrew; Beard, Tony (2004). London's Secret Tubes. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-283-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Horne, Mike (2006). The District Line. Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-292-5.

- Lee, Charles Edward (May 1970). Seventy Years of the Central. Westminster: London Transport. ISBN 0-85329-013-X. 570/1111/RP/5M.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rose, Douglas (1999) [1980]. The London Underground, A Diagrammatic History. Douglas Rose/Capital Transport. ISBN 1-85414-219-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wolmar, Christian (2005) [2004]. The Subterranean Railway: How the London Underground Was Built and How It Changed the City Forever. Atlantic Books. ISBN 1-84354-023-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Central London Railway. |