Blyth and Tyne Railway

Blyth and Tyne Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

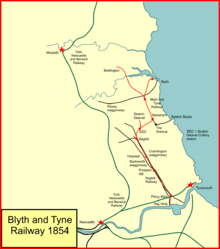

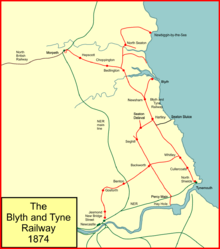

The Blyth and Tyne Railway was a railway company in Northumberland, England. It was incorporated in 1853 to unify several private railways and waggonways that were concerned with bringing coal from the Northumberland coalfield to Blyth and to the River Tyne. Over the years it expanded its network to include Ashington, Morpeth and Tynemouth. As coal output increased the company became very prosperous in hauling the mineral to quays for export, and in addition a residential passenger service based on Newcastle built up.

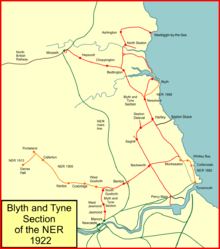

It was absorbed by the much larger North Eastern Railway in 1874, and some integration of service and facilities took place, but the Blyth and Tyne section retained its individual identity. In 1904 electric traction was introduced for suburban passenger trains on north Tyneside and part of the Blyth and Tyne system was electrified; the new trains proved a considerable success. Speculative branch lines built in the twentieth century were less successful.

In the period from 1975 coal extraction declined, and parts of the Blyth and Tyne system that were dependent on the mineral traffic suffered accordingly, and the passenger business too declined. At the end of the 1970s the decision was taken to establish a light rapid transit system, the Tyne and Wear Metro, based on the North Tyneside network at first, and this started operating in 1980, using part of the Blyth and Tyne routes. Most of the remainder of the former system has no railway activity now.

History

Before the Blyth and Tyne Railway

From the seventeenth century, coal had been extracted in the area north of the River Tyne, at first close to the river to allow onwards transport by boat. As the easiest deposits close to the river became worked out, the focus of mining was pushed back further, and transport to the waterway was essential. Wooden waggonways were introduced and were relatively successful, but a major limitation was the issue of wayleaves, by which owners of land on the proposed route could demand payment, usually on a tonnage basis, for allowing the passage of the wagons. The wayleave demands were heavy, and this continued to be a major difficulty.

Wallace recorded that "in 1723, Plessy colliery was in the hands of Richard Ridley; and as he was a man of both wealth and enterprise he would in all probability make the railway by which the coals then came to Blyth". The harbour at Blyth was used for the onward transport by coastal shipping.[1]

Mining of the early Northumberland Coalfield was taking shape. In 1794 a colliery was commenced within a mile of Cowpen, which at once brought a large increase of population and trade. "An Act of Parliament was obtained, and Cowpen Quay was erected... [About 1812] when Plessy Colliery was discontinued, a railroad was made to connect Cowpen Colliery with Blyth, as we have it at the present time, and instead of the coal being shipped at Cowpen Quay it was sent to Blyth."[1]

The Plessy waggonway played a peripheral role in the Napoleonic Wars:

One Sunday morning in the year 1811, the inhabitants [of Blyth] were thrown into a state of great excitement, by the startling news that five Frenchmen had been taken during the night, and were lodged in the guard-house. They were officers who had broken their parole at Edinburgh castle, and in making their way home had reached the neighbourhood of Blyth; when discovered they were resting by the side of Plessy wagon-way, beside the "shoulder of mutton" field.[1]

The railway had timber track:

The railway was constructed of a double line of beech rails, and laid upon oaken sleepers. The railway from Plessy continued to be made of wood till the road was discontinued in 1812. Originally the wagons had wooden wheels, and to prevent the wear and tear of the wheels, which were extremely expensive to maintain, they were studded with nails driven up to the head... Each wagon required a horse, and a man to conduct it; three journeys or "gaits", as they were termed, was a day’s work.[1]

There was considerable expenditure on new pits at Seghill and Cramlington in 1822 and 1823. The Tyne was six miles away and the problem of transport to water arose once again. The Cramlington waggonway was only two miles away, however. It was opened in 1822 and ran from the pit later known as Ann Pit to Murton Row where it joined the Backworth line. Backworth Colliery had had a primitive railway, but the section between Backworth and Allotment was converted to rope haulage by stationary steam engine in 1821. Two years later the incline between Allotment and Percy Main was altered and eased, and the whole line was rope worked by 1827. About 1838 the line was extended north-westwards to West Cramlington, and when the Newcastle and Berwick Railway was constructed, a junction was made with it there.[2]

In 1839 the Seaton Delaval coal company sunk a new pit, and formed a waggonway 1¼ miles in length from there to Mare Close where it was connected to the Cramlington line. In the same year the Cramlington company, considering that their dependency on the congested Backworth line was becoming impossible, constructed their own line to the staiths, parallel to, and to the east of, the Backworth line, leaving it at Murton Row.[2][3]

The Seghill Railway

The Seghill colliery owner was also dissatisfied with the route to the staiths, and in early 1839 Robert Nicholson made a survey for a private mineral railway from Seghill to Howdon. Nicholson had been engineer of the Newcastle and North Shields Railway, which was shortly to open. The owners of the colliery at Seghill had used the Cramlington waggonway,[2] owned by the Cramlington Coal Company, but the latter favoured its own traffic and put obstructions in the way of the Seghill coal.

The main part of the route ran straight south east, crossing the old line of the Cramlington Coal Company by a low timber bridge of two laminated arches each of 81 feet 6 inches (24.84 m) span.

There were steep gradients on the line; from Seghill to Prospect Hill rising as steep as 1 in 61, and from Prospect Hill to the Tyne falling gradients, the steepest of which was 1 in 25. The line was worked mainly by stationary engines, one at Prospect Hill, near the Allotment, which hauled up the loaded wagons from Holywell, and the empty wagons from the Newcastle and North Shields road. The other engine was at Percy Main, hauling the empty wagons from the staiths. From Prospect Hill to Percy Main and from Percy Main to the staiths the loaded wagons ran by gravity, unwinding as they descended a tail rope from the drum of the engine, to bring hack the empty wagons. The remainder of the line from Seghill to Holywell was worked by locomotives; those used at first were the Samson and the John, both built by Timothy Hackworth.[3]

The Newcastle and North Shields Railway contemplated building an extension of the Seghill line to Blyth, but the takeover of the N&NSR by the Newcastle and Berwick Railway diverted attention to wider horizons.[2]

Harbours

The onward transport of coal by water was restricted by the fact that the only harbours available were at Blyth and Seaton Sluice, both of them small and incapable of handling larger vessels. From 1842, the Bedlington Coal Company developed a novel method of shipping its coal: loaded chaldron wagons, 40 at a time, were taken in an iron twin-screw steamer, the Bedlington, from the staiths on the north side of the River Blyth near Mount Pleasant to Shields Harbour; there they were discharged into the coastal shops by means of steam derricks fitted to Bedlington. This arrangement continued in use until 1851. Other proposals involved further railways and waggonways but for the time being they were not implemented.[3]

Nevertheless, the limitation of Blyth as a harbour spurred consideration of a railway connection directly to the Tyne, and it was this cause that led ultimately to the formation of the Blyth and Tyne Railway.[4]

The Blyth and Tyne Junction Railway

From 25 June 1844, the Newcastle and North Shields Railway (N&NSR) worked the passenger and goods traffic on the Seghill Railway, but in November 1844 George Hudson, "The Railway King," made a provisional agreement with the N&NSR to merge that undertaking with the Newcastle & Berwick Railway which he was promoting at the time; the N&NSR gave his Berwick company access to central Newcastle. When the N&NSR was authorised on 31 July 1845, the arrangement was confirmed. In the changed circumstances the Seghill Railway and the projected extensions assumed a new importance. In July 1845, Jobling & Partners decided to construct a part of the proposed railway, and, by forming a junction with the Seaton Delaval Railway and arranging for the connection of that railway with the Seghill Railway, to create a route to the Tyne. The line was named the Blyth and Tyne Junction Railway. Construction was started in August 1845, but the line was not opened for passenger traffic until 3 March 1847;[1] on that date the whole 4½ miles between Seghill and Blyth began to cater for passengers.[3]

Bedlington extension

Bedlington colliery needed to be connected to the network, and on 12 June 1850 a private line was opened from the colliery to Newsham, a distance of 2¾ miles. Mineral traffic only was carried at first, but it was opened for passengers also on 1 August 1850. In effect this was an extension of the growing Blyth and Tyne Railway; it crossed the River Blyth by a timber viaduct 80 feet in height and 770 feet in length. Described as a "splendid viaduct" by newspapers, it was designed by Robert Nicholson.[5]

Incorporation of the Blyth and Tyne Railway

There were now several separate private railways, and there was a movement to make them into a single, incorporated company. The spur was passenger duty imposed on private railways, and also concern about promotion of a possible competing railway. They connected two parts of the group together by cutting through Prospect Hill in the year 1851 to enable the adoption of locomotive power; the new cut formed considerably gentler gradients. With other improvements the expenditure was about £130,000. The Act incorporating the Blyth and Tyne Railway received the Royal Assent on 30 June 1852, capital £150,000. The line controlled by the new company totalled 13 miles, consisting of the main line from Blyth to the Hayhole on the Tyne (12 miles), a short branch to the York. Newcastle & Berwick Railway at Percy Main, the connection with the former Newcastle & North Shields Railway, and several short branches to shipping places on the Tyne. The new Company came into existence on 1 January 1853.[2][3]

A rival company, the Tynemouth Docks & Morpeth & Shields Direct Railway, proposed a dock at the Low Lights, North Shields, and a railway from Morpeth running directly to North Shields, with branches to Ashington and Seaton Sluice. The Blyth and Tyne Railway deposited Parliamentary plans for lines occupying part of the same ground to spoil the competing line, and both proposals went to Parliament.

The promoters of the Tynemouth Docks Direct Railway hoped to take advantage of avoiding the cost of wayleaves with which the Blyth and Tyne was burdened, and the B&TR found itself uniting with the landowners who imposed these charges against the newcomer. Its reward was a concession by the landowners, reducing their terms by a third. The Tynemouth Dock Bill was thrown out in Parliament, and the Blyth and Tyne Railway succeeded in getting the powers it had applied for, by Act of 4 August 1853. There was to be a branch from Newsham to Morpeth and another from New Hartley to the Dairy House near Seaton Delaval, a line ultimately planned to reach Tynemouth. The B&TR intended to buy some existing private lines and continue one of them to Morpeth. The B&TR was committed to the completion of a line to Tynemouth and in 1854 obtained Parliamentary authorisation to make this extension, as well as a building a branch from Bedlington to Longhirst.[3]

Improvements

From 1855 a number of extensions were built to consolidate the network. Prospect Hill was further improved and double track provided over six miles of railway, and more staiths were built in the Tyne. They purchased two short colliery lines which formed portions of their main line between Seaton Delaval and Hartley and between Bedlington and Newsham, and constructed the branch line to Morpeth. They also planned the eastward extension to Whitley and Tynemouth. Northumberland Dock was opened on 22 October 1857 and their presence there was a valuable asset in taking Northumberland steam coal to market. On 1 October 1857 the Morpeth branch was opened for mineral traffic, and on 1 April 1858 for goods and passenger traffic.[3]

In 1855 passengers on the Blyth and Tyne were conveyed in low-roofed springless carriages locally called "bumler boxes," but the Company decided to improve the passenger carriages while they made the network extensions. The company obtained new passenger rolling stock of modern design. The third class carriages were of a type then probably unsurpassed elsewhere in the country. They were designed in 1854, and twenty years later had given such satisfaction that the travelling public desired no change.[6]

North British Railway

In the period from 1857 the North British Railway was frustrated by its dependency on the North Eastern Railway (which had taken over the York, Newcastle and Berwick Railway in 1854). It had proved a wily partner in the traffic between Edinburgh and Newcastle. The NBR was anxious to secure independent access to Newcastle if possible. The NBR supported the promotion of the Border Counties Railway, which was being built in stages from Hexham, on the Newcastle and Carlisle Railway to Riccarton on the Border Union Railway (which became known as the Waverley Route). Although this was to be a slow and circuitous line, mostly single line through thinly populated terrain, it served the NBR purpose of providing, or at least threatening, a separate route to Newcastle from the north. However the Newcastle and Carlisle Railway was not unfriendly to the YN&BR and might prove an uncertain ally.

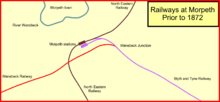

The Wansbeck Railway was then promoted, with the intention of forming a connection between Reedsmouth on the Border Counties Railway and Morpeth. The commercial viability of this line was even more shaky—Lee says "a thinly-populated district without manufactures and with very few mineral resources"—than the Border Counties Railway, but it gave access to Morpeth, avoiding the Newcastle and Carlisle Railway altogether. If the Blyth and Tyne Railway could be befriended, then the desired access to Newcastle was secure—but by a very roundabout route.

When the Wansbeck Railway was constructed, the North British (who were in control of it) considered how to connect to the Blyth and Tyne at Morpeth. That company's station was alongside, but on the south side of, the York, Newcastle and Berwick station, and direct connection was difficult. (Running over the YN&BR line, even for a few yards, would defeat the notion of independence.) In fact the Wansbeck line crossed the YN&BR line by a bridge and connected to the Blyth and Tyne line further east. For simple through running that was practicable, but in the event only local traffic ran, and all of that started or ended at Morpeth B&T station. This involved reversal at the point of junction, and propelling between there and the station.

This was a dangerous practice, and a collision took place in 1871 from that cause. By then hopes of independent main line running to Newcastle were over, and in 1872 the Wansbeck line was diverted to connect into the YN&BR station in the ordinary way.[7] The Blyth and Tyne station at Morpeth remained in use for tis own passenger trains until 24 May 1880, after which B&T trains used the NER station.[4]

Extension to Newcastle, and others

The Chairman of the Blyth and Tyne Railway, Joseph Laycock, proposed to build an extension to Newcastle. The necessary Parliamentary Act was secured on 1 May 1861. It authorised the extension to Newcastle, as well as some branches, forming the loop from Newcastle through South Gosforth and Benton to Monkseaton; and from Seghill to the Seaton Burn waggonway, from Bothal Demesne (North Seaton) to Newbiggin, and from the B&TR existing line at Tynemouth to proposed docks at the Low Lights.[3]

The Blyth & Tyne line between the Dairy House and Tynemouth was opened on 31 October 1860.

The new extension from Hotspur Place (near Benton) to Newcastle, and from Hotspur Place to Monkseaton in the other direction, was formally opened on 22 June 1864; the public opening took place on the 27 June. The Newcastle terminus was at New Bridge Street,[8] on the north side of the city beyond the present-day Manors station; it was designed by John Dobson, who had also designed the Central station.

At the same time a further connection was made at Tynemouth, where an extension ran from the earlier terminus of 1860 to a location close to the North Eastern Railway station there. The Blyth and Tyne Railway charged the same fares to Tynemouth as the North Eastern Railway, and the new line was extremely well patronised: 17,000 passengers, mostly third class, were carried during the first week. Third class business was proving popular and the B&TR announced that from 1 October 1864 third class travel would be available on all trains. Third class carriages had formerly only been attached to one train each way daily; misgivings that this would abstract income by trading down were stated by the Chairman to have been misplaced.[9]

In 1867 a branch was opened extending the Bedlington stub eastwards to Cambois, on the coast north of the River Blyth.[4]

Some years elapsed before the opening of the final extension of the Blyth and Tyne Railway during its independent days: on 1 March 1872 the Newbiggin branch of 3½ miles was opened. It joined the Cambois branch at West Sleekburn Junction.[3]

Amalgamation

During 1872 the North Eastern Railway approached the Blyth and Tyne Railway to discuss a merger. The directors of the B&TR were agreeable, but they held out for the best terms they could get, and towards the end of January 1874, terms of amalgamation were settled. The North Eastern Railway would guarantee a dividend of 10 per cent on Blyth and Tyne ordinary stock (then capitalised at £315,000) and to pay £50,000 in cash for distribution among the ordinary shareholders, as well as taking on all the liabilities of the B&TR. The merger was ratified by Act of Parliament of 7 August 1874.[3]

The Blyth and Tyne section of the North Eastern Railway continued to have an individual identity.

Whitley Bay new line

When the Tynemouth branch had been built in 1860, it ran north to south from Monkseaton (at first called Whitley) at some distance from the coast. As residential travel increased in subsequent decades, the emphasis was on locations nearer the coast. The Blyth and Tyne Railway had obtained powers to build a parallel line to serve those areas in 1872, but the authorisation was never put into effect. After the amalgamation, the north Eastern Railway decided to reactivate the powers, and obtained a fresh Act of Parliament on 29 June 1875. There was still delay in carrying out the work, but on 3 July 1882 the new line opened. It ran to make an end-on connection (from the east) with the existing Tynemouth terminus, and a lavish new station was provided there. A new station was provided at Monkseaton on the new line, and a complex layout of short spurs connected it into the old system there. Whitley Bay and Cullercoats also had new stations. (Whitley Bay was further enlarged in 1910.) The old route from Monkseaton to Tynemouth was closed down, except for a short length at Tynemouth used to access the goods depot there.[4]

North Blyth

In 1867 the Cambois branch had been opened. In 1893 further expansion was necessary on the River Blyth and extensive facilities were provided on the north bank; rail connection was provided by extending the Cambois line. This work was commissioned on 13 July 1896; at the same time a curve was installed near Sleekburn Junction giving direct running from North Blyth towards Ashington; this was brought into use at the same time. In 1903 the North Eastern Railway introduced 40-ton bogie coal wagons to operate a shuttle service between Ashington and North Blyth.[4]

Locomotives

Most of the Blyth and Tyne locomotives were of the 2-4-0 and 0-6-0 type' the 2-4-0s mostly had 5 ft 6 in wheels and two 16 by 24-inch cylinders; working boiler pressure was typically 140 lb. The 0-6-0 goods engines had the same size of cylinder but the wheels were of 4 ft 6 inch diameter. In the 1860s a three-cylinder 0-6-0 engine was built . After the electrification of 1904, steam autocar trains composed of a Fletcher BTP 0-4-4T engine between two coaches operated on the Monkseaton-Shields section, operating a shuttle passenger service over the Avenue branch from Blyth to North Shields.[3]

Electrification

Residential travel into Newcastle and Gateshead developed considerably in the latter years of the nineteenth century. Street-running tramcars were introduced from 1878, and in 1901 the system was converted to electric traction,[10] representing a considerable step forward in convenience for the public, and competition for suburban railways. The total number of passengers booked in the Newcastle area in 1901 was 9,847,000 but by 1903 this had fallen to 5,887,000.[4]

In response, the North Eastern Railway electrified what became known as the North Tyneside Loop, much of which was part of the Blyth and Tyne system, between New Bridge Street, Backworth, Monkseaton and Wallsend. This was the first part of a network of suburban electrified routes, the Tyneside suburban electric system.

The Railway Magazine recorded the opening:

On Tuesday, March 29, 1904, at 12.50 p.m. electric working for public traffic was put into operation on the North-Eastern Railway; the line on which the new motive power is employed being that between New Bridge Street Station (Newcastle) and Benton, a distance of 4 miles 7 chains... The outward journey took 11 minutes, the inward 12 minutes, being a reduction of 25 per cent, on the time occupied by steam-hauled trains... There are 37 miles of double and four-way track [in the North Tyneside suburban network], equivalent to some 82 miles of single track, over the whole of which the passenger service will in the near future be worked electrically. For the present the goods traffic will be mainly operated by steam, although two electric goods locomotives are to be used on a portion of the system...

The third rail system is adopted, the current being picked up by a contact shoe from this rail... and after passing through the motors returns to the dynamos [at the generating station] by the ordinary running rails. The current is generated at high pressure, 6,000 volts three-phase alternating, at the central power station, and transmitted to sub-stations, where it is converted into low pressure 600 volt direct current, and fed on to the rails.

The electric power was to be procured from the Newcastle upon Tyne Electric Supply Company. The trains would be multiple units: "each train consists of three bogie coaches, one a third-class smoking vehicle, the centre a third-class carriage for non-smokers, and the last a first-class coach with luggage compartment."[11]

New carriage sheds were erected at South Gosforth and as part of the preparation for electrification, a spur was built from south to west at Benton, for empty stock to reach the sheds from the main line. It opened on 1 May 1903. A south to east curve was opened nearby on 1 July 1904 giving express electric trains access between the coast and Newcastle via the main line. A north spur from South Gosforth East to South Gosforth West was opened in 1905 (associated with the Ponteland branch), giving empty stock trains easier access to the carriage depot.[4]

In 1902 a north to west curve was authorised at the Benton crossing, but not built at the time. In fact it was commissioned in 1940 to give an alternative route from the main line into Newcastle in the event of enemy attack closing the main line.[4]

Ponteland branch

In 1905 the Ponteland branch opened; it left the former Blyth and Tyne system by a junction at South Gosforth. It was built under Light Railway legislation. As a speculative line it was intended to electrify it when residential traffic had built up sufficiently. However the results were disappointing, and the passenger service was operated throughout its life by a steam autocar. A stub from Ponteland to Darras Hall was opened on 1 October 1913, and fared no better. Both lines closed to passengers on 17 June 1929.[4] A goods service continued to Darras Hill until 1954, to Ponteland until 1967, and to a private siding at Callerton until 1989.[12]

In 1922 there were six weekday passenger trains on the branch with an additional Saturday train; only three ran through to Darras Hall.[13]

The Metro route to Newcastle Airport now follows part of the line of route.

Manors connection

Although trains from the Tynemouth part of the Blyth and Tyne section could run direct to Newcastle Central station, the South Gosforth line terminated at New Bridge Street. The terminus was only a short distance from the former Newcastle and North Shields Railway main line at Manors, and in 1909 a short connecting line was laid in, enabling through running to and from Central station. Although trains could now run Central to Central by a circular route, for some years this was not done, and only trains from Central to South Gosforth used the connection, other services continuing to terminate at New Bridge Street. From 1 March 1917 the arrangement was rationalised, and trains ran throughout over the connecting line/.[4]

Collywell Bay line

Starting in 1912 North Eastern Railway constructed a branch line from a junction a mile to the north of Monkseaton station to Seaton Sluice, the site of a proposed housing development. It was to be part of the electric network, and the North Eastern Railway felt that "Seaton Sluice" was an unattractive name to encourage new residents, so it was determined to call the station "Collywell Bay". The two mile long line was to have one intermediate stop at Brierdene. Construction was well advanced, with an anticipated opening date of November 1914, but was halted at the commencement of World War I, and in 1917 the track was removed for use in France and recycling elsewhere. A mile long section of the track was reinstated so that a rail-mounted naval gun could be deployed on it. After the war the line was left unfinished; in 1924 a review estimated that rehabilitation would cost £50,000, and the scheme was shelved. In 1931 the branch was formally abandoned.[4][14]

Walker Gate fire

In August 1918 a disastrous fire took place in the carriage sheds at Walker Gate. As well as the damage to the building, thirty-four vehicles from the electric fleet were destroyed, and many others badly damaged. A scratch service of mixed steam and electric traffic was instituted and replacement vehicles hurriedly ordered, but it was not until 1922 that a full fleet, and a normal train service, could be counted on. South Gosforth car sheds were considerably expanded at this time.[4]

After 1923

The Railways Act 1921 resulted in the main line railways of Great Britain being "grouped" in 1923; the North Eastern Railway became part of the new London and North Eastern Railway (LNER). In turn the railways of Great Britain were nationalised in 1948, and the former NER lines became the major component of the North Eastern Region of British Railways.

Blyth rose steadily to prominence in exporting coal and extensive further staiths were provided there between 1926 and 1928. Over six million tons of coal were exported annually in the 1930s; about 90% of coal exported comes from collieries within six miles.

In the period after World War II until 1970, boat trains from London ran to Tyne Commission Quay via Percy Main in connection with Scandinavian ferry services. There was a connecting curve between the North Shields line and the B&T line; the B&TR had a Percy Main station actually on the curve. The boat trains ran from Newcastle on to the curve as far as Percy Main North. There they reversed and passing under the North Shields line they ran on to the Tyne Improvement Commission network to reach the Quay.[8]

Passenger services were withdrawn from the lines to Ashington and Blyth in 1964. Faced with declining passenger business and the requirement for considerable expenditure to renew the electrical systems and rolling stock on the electric network, the remaining routes reverted to diesel traction in 1967.

Tyne and Wear Metro

Renewed attention to suburban public transport in the 1970s led to the creation of the Tyne and Wear Metro, a light rapid transit system, much of which operated on the old Blyth and Tyne routes.

The modernisation of the existing routes and the necessary conversion to light rapid transit configurations resulted in suspension of the existing passenger services on the affected routes in 1978 - 1979. The Metro services started operation in 1980. Some of the former routes were retained for heavy rail operation of mineral and goods trains, but the decline of the Northumberland Coalfield in the 1980s and 1990s has reduced this traffic.

The Metro system uses the Blyth and Tyne route from Newcastle to South Gosforth and on through Benton to Tynemouth; in addition the Airport branch uses part of the Ponteland branch, constructed after the end of the independent existence of the B&TR but regarded as part of the B&TR network.

Proposed reinstatement of passenger services

1990-2009: Early proposals

There have been proposals to reintroduce passenger services to part of the ex-B&TR system since the 1990s. Denis Murphy, the then Labour MP for Wansbeck, expressed support in the House of Commons in an adjournment debate in April 1999 and again in a debate in January 2007.[15] The Railway Development Society (renamed Railfuture in 2000) endorsed the proposal in 1998.[16]

In 2009 the Association of Train Operating Companies published a £34 million proposal to restore passenger services to the north-eastern part of the B&TR system. It would have included reopening stations at Seaton Delaval, Bedlington, Newsham (for Blyth) and Ashington.[17]

2013-2017: Initial plans and the Ashington, Blyth & Tyne Line project

In the early 2010s Northumberland County Council (NCC) became interested in the reintroduction of passenger services onto remaining freight-only sections of the network. In June 2013 NCC commissioned Network Rail to complete a GRIP 1 study to examine the best options for the scheme.[18] NCC received the GRIP 1 study in March 2014 and in June 2015 it commissioned a more detailed GRIP 2 feasibility study at a cost of £850,000.[19]

The GRIP 2 study, which NCC received in October 2016,[20] confirmed that the reintroduction of a frequent seven-day a week passenger service between Newcastle and Ashington was feasible and could provide economic benefits of £70 million with more than 380,000 people using the line each year by 2034.[21] The 2016 GRIP 2 study envisaged a project (at the time referred to as the Ashington, Blyth & Tyne Line (ABT)), at an estimated cost of £191 million,[21] involving construction of new or reopened stations at Northumberland Park (for interchange with the Tyne and Wear Metro), either Seghill or Seaton Delaval, Newsham, Blyth Park & Ride, Bedlington, Ashington and Woodhorn (for the Woodhorn Colliery Museum and Northumberland Archives) with a potential end to end journey time of 37 minutes.[22] At the time, it was suggested that detailed design work could begin in October 2018 with construction commencing four months later and the first passenger services introduced in 2021[21] though by October 2018 such works were yet to begin.

After receiving the GRIP 2 study, NCC initially announced that it was proceeding with a GRIP 3 Study from Network Rail. However, such a report was not commissioned at the time.[23] Despite a change in the political leadership of Northumberland County Council following the 2017 local elections[24] the authority continued to work towards the reintroduction of a passenger service onto the line,[25] encouraged by the Department for Transport's November 2017 report, A Strategic Vision for Rail, which named the line as a possible candidate for a future reintroduction of passenger services.[26][27] Consequentially, NCC commissioned a further interim study in November 2017 (dubbed GRIP 2B) to determine whether high costs and long timescales identified in the GRIP 2 Study could be reduced by reducing the initial scope of the project, but the report failed to deliver on this.[23]

2019-present: Revised plans and the Northumberland Line project

The county council has, however, continued to develop the project and, on 8 February 2019, chartered a train from Northern that carried the then Secretary of State for Transport Chris Grayling and other dignitaries over part of the route (now rechristened the Northumberland Line) between Morpeth and Newsham,[28] after which NNC announced an additional £3.46 million in funding for a further business case and detailed design study[29] (equivalent to GRIP 3)[23] to be completed by the end of 2019. It is envisaged that passenger trains could be introduced as early as 2022.[29] A Strategic Outline Business Case for the project, prepared by AECOM and SLC Rail in March 2019, reiterated the economic benefits of the project, again suggesting that it could boost the local economy by up to £70 million.[30] The Campaign for Better Transport has identified the line as a Priority 1 candidate for reopening.[31]

The revised proposals, released in July 2019, are reduced in scope from the plan considered in the 2016 GRIP 2 study and propose a four-phase project[32] allowing a reduction in the initial cost of the scheme; the initial phase, at an estimated £90 million,[29] would see the creation of new or reopened stations at Northumberland Park, Newsham, Bedlington and Ashington as well as some line-speed upgrades, extension of the double track section further to the south of Newsham, creation of turn-back facilities at Ashington and some level crossing upgrades or closures.[32] Two further stations, at Seaton Delaval and Blyth Bebside (formerly Blyth Park & Ride), and additional line-speed improvements are suggested for Phase 2 while Phases 3 and 4 would deliver further line-speed improvements (including signalling upgrades) and an additional passing-loop at Seaton Delaval respectively.[32] Previously proposed stations at Seghill and Woodhorn appear to have been dropped from the scheme.

The North East Joint Transport Committee's bid for £377 million of funding from the UK Government's £1.28 billion Transforming Cities Fund, submitted on 20 June 2019, includes £99 million to fund the reintroduction of passenger services between Newcastle and Ashington,[33] while further work is ongoing to secure additional public and private investment for the project.[30]

Rail minister Chris Heaton-Harris visited Bedlington station in January 2020, and announced a grant of £1.5 million to Northumberland County Council towards development of the proposals.[34] By February, Northumberland County Council had agreed a further £10 million in funding to progress the proposals, with the possibility of construction beginning as early as June 2022, for a September 2023 opening.[35]

Topography

Passenger station opening and closing dates:

Newcastle to Morpeth

- (Newcastle upon Tyne Central)

- (Manors North)

- New Bridge Street; opened as terminus 27 June 1864, and at first simply known as "Newcastle"; popularly known as "the station in the Manors" in the early years; from 1850 when the Manors station of the YN&BR was opened, this station began to be known as the Carliol Square station";[36] closed 1 January 1909, when trains ran through to Central;

- Jesmond; opened 27 June 1864; closed 23 January 1978;

- West Jesmond; opened 1 December 1900; closed 23 January 1978

- Moor Edge: opened ; opened 1 May 1872; closed in 1882

- Gosforth; opened 27 June 1864; renamed South Gosforth 1905; closed 23 January 1978;

- Longbenton; opened 14 July 1947; closed 23 January 1978;

- Benton; opened 27 June 1864; may have been named Longbenton; replaced by a new Benton some distance to the east; closed 23 January 1978;

- Forest Hall: opened 27 June 1864; closed 1 March 1871; an NER station ex Benton adopted this name later;

- Benton Square; opened 1 July 1909; closed 20 September 1915;

- Hotspur; opened 27 June 1864; renamed Backworth 1865; closed 13 June 1977;

- Holywell; opened 28 August 1841; renamed Backworth 1860; closed 27 June 1864;

- Seghill; opened 28 August 1841; closed 2 November 1964;

- Seaton Delaval Colliery; opened 3 March 1847; renamed Seaton Delaval 1864; closed 2 November 1964;

- Hartley Pit; opened 3 March 1847; renamed Hartley; resited to the north 1851; closed 2 November 1964;

- Newsham; opened 1850; closed 2 November 1964;

- Cowpen Lane; opened 3 August 1850; renamed Bebside 1860; closed 2 November 1964;

- Bedlington; opened 3 August 1850; closed 2 November 1964;

- Choppington; opened 1 April 1858; closed 3 April 1950;

- Hepscott; opened 1 April 1858; closed 3 April 1950;

- Morpeth; opened 1 April 1858; closed 24 May 1880 when trains transferred to NER station.

Hotspur to Tynemouth (first line)

- Hotspur (above);

- West Monkseaton; opened 20 March 1933; closed 10 September 1979;

- Whitley; opened 1 April 1861; relocated 27 June 1864; renamed Monkseaton and again relocated on new line 1882 (below);

- Cullercoats; opened 27 June 1864; relocated on new line 3 July 1882 (below);

- Tynemouth; opened 1 April 1864; relocated 27 June 1864; renamed North Shields 1865 when new terminus opened; replaced by station on new line 3 July 1882 (below).

Whitley Bay new line (NER)

- Monkseaton; opened 3 July 1882; closed 10 September 1979;

- Whitley; opened 3 July 1882; renamed Whitley Bay 1899; closed 10 September 1979;

- Cullercoats; opened 3 July 1882; closed 10 September 1979;

- Tynemouth; through station, opened 3 July 1882; closed from the Monkseaton direction 10 September 1979, and from Wallsend direction 11 August 1980.

Hartley to Monkseaton

- Hartley (above);

- Dairy House; opened 1 April 1861; renamed The Avenue later in 1861; closed 27 June 1864; summer Sundays usage shown in timetables in 1872 and 1874;

- Monkseaton (above).

Blyth branch

- Blyth; opened 3 March 1847; relocated 1867; closed 2 November 1964;

- Newsham (above).

Newbiggin branch

- Newbiggin-by-the-Sea; opened 2 November 1859; closed 2 November 1964;

- Hirst; opened June 1878; renamed Ashington 1889; closed 2 November 1964;

- North Seaton; opened 2 November 1859; closed 2 November 1964;

- Bedlington (above).

References

- Wallace, John (1869). The History of Blyth from the Norman Conquest to the Present Day. Blyth: John Robinson Junior.

- Wells, JA (1989). The Blyth and Tyne Railway. Northumberland County Library. ISBN 0-951-3027-4-4.

- Lee, Charles E, May & June 1943, "The Blyth and Tyne Railway", The Railway Magazine

- Hoole, K (1965). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain. 4, The North East. Dawlish: David and Charles.

- "`". North & South Shields Gazette and Northumberland and Durham Advertiser. 14 June 1850.

- Newcastle Chronicle, 1 September 1874, quoted by Lee

- G W M Sewell, The North British Railway in Northumberland, Merlin Books Ltd, Braunton, 1991, ISBN 0-86303-613-9

- Hoole, K (1994) [1973]. Forgotten Railways: North-East England (revised ed.). Newton Abbot: David and Charles. ISBN 978-0946537105.

- Report of Shareholders' Meeting in the Newcastle Journal, 21 February 1865

- Purdue, AW (2012). Newcastle, the Biography. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4456-0934-8.

- Electric Train Services on the North-Eastern Railway in Railway Magazine, April 1904

- Cobb, Col MH (2003). The Railways of Great Britain — A Historical Atlas. Shepperton: Ian Allan Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-7110-3003-0.

- Bradshaw's Railway Guide (reprint ed.). London: Guild Publishing. 1985 [1922].

- "Collywell Bay Station". Disused Stations. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- Denis Murphy; et al. (10 January 2007). "Ashington, Blyth and Tyne Railway". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Commons. col. 135WH–139WH.

- Bevan 1998, p. 59.

- "Connecting Communities – Expanding Access to the Rail Network" (PDF). London: Association of Train Operating Companies. June 2009. p. 17. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- "Ashington Blyth and Tyne rail line restoration scheme gets green light". The Journal. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- "Plans for rail line reach milestone". News Post Leader. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- Ashington, Blyth & Tyne Line (PDF). Northumberland County Council. 2016.

- "Reopening of Newcastle to Ashington rail link moves one step closer". Evening Chronicle. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- "Ashington Blyth & Tyne GRIP 2 Study" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- "SENRUG - South East Northumberland Rail User Group: Re-open Ashington Blyth & Tyne Line". Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- Kelly, Mike; Muncaster, Michael (5 May 2017). "Northumberland local elections results IN FULL – council held by Tories in 'straw draw' drama". Evening Chronicle. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Graham, Hannah (1 June 2018). "Northumberland's draft local plan unveiled: What it means for houses, jobs and the green belt". Evening Chronicle. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- "Connecting people: a strategic vision for rail" (PDF). Department for Transport. November 2017. ISBN 9781528601252. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Allen, Andrew (12 December 2017). "What's in the government's new rail strategy?". CityMetric. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Sharma, Sonia (8 February 2019). "Transport Secretary Chris Grayling backs plans for Ashington to Newcastle passenger trains". Evening Chronicle. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- O'Connell, Ben (28 February 2019). "Phasing of proposed Northumberland rail line explained after concerns raised". News Post Leader. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- "Northumberland Line could reopen for passengers in 2022". Rail Engineer. 28 March 2019. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- The case for expanding the rail network (PDF). Campaign for Better Transport. 2019. p. 32.

- O'Connell, Ben (15 July 2019). "Six new stations could open if Ashington to Newcastle passenger trains resume". Evening Chronicle. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Holland, Daniel (19 June 2019). "North East's £377m transport funding bid confirmed – but leaders say there is more to come". Evening Chronicle. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- Sharma, Sonia (28 January 2020). "How plans to re-open Newcastle to Ashington railway line could boost region". North East Chronicle. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- "£162m Northumberland Line scheme moves to design phase". The Contruction Index. 14 May 2020. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Addyman, John; Fawcett, Bill (1999). The High Level Bridge and Newcastle Central Station. North Eastern Railway Association. p. 19. ISBN 1-8735-13-28-3.

Sources

- Bevan, Alan, ed. (1998). A-Z of Rail Reopenings (fourth ed.). Fareham: Railway Development Society Ltd. p. 59. ISBN 0-901283-13-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Hoole, K (1987). North Eastern Electrics: The History of the Tyneside Electric Passenger Services, 1904–67. Usk: Oakwood Press. ISBN 978-0853613589.

- Rhodes, Michael (September 1988). "The Blyth & Tyne past, present and future". RAIL. No. 84. EMAP National Publications. pp. 41–46. ISSN 0953-4563. OCLC 49953699.

External links

- Crawford, Ewan. "Blyth and Tyne Railway". A History of Britain's Railways. Railscot.

- Local historical article on Plessey Wagonway